Tag Archives: Mary Treadgold

Paul Auster Reading Week, II: Baumgartner & Travels in the Scriptorium (#AusterRW25 #ReadIndies)

It’s the final day of Annabel’s Paul Auster Reading Week and, after last week’s reviews of Invisible and Siri Hustvedt’s The Blindfold, I’m squeaking in with a short review of his final novel, Baumgartner, which Annabel chose as the buddy read and Cathy also wrote about. I paired it at random with another of his novellas and found that the two have a similar basic setup: an elderly man being let down by his body and struggling to memorialize what is important from his earlier life. They also happen to feature a character named Anna Blume, and other character names recur from his previous work. I wonder how fair it would be to say that most of Auster’s novels have the same autofiction-inspired protagonist, and are part of the same interlocking universe (à la David Mitchell and Elizabeth Strout)?

Baumgartner (2023)

Sy Baumgartner is a Princeton philosophy professor nearing retirement. The accidental death of his wife, Anna Blume, a decade ago, is still a raw loss he compares to a phantom limb. Only now can he bring himself to consider 1) proposing marriage to his younger colleague and longtime casual girlfriend, Judith Feuer, and 2) allowing a PhD student to sort through reams of Anna’s unpublished work, including poetry, translations and unfinished novels. The book includes a few of her autobiographical fragments, as well as excerpts from his writings, such as an account of a trip to Ukraine to explore his heritage (elsewhere we learn his mother’s name was Ruth Auster) and a précis of his book about car culture.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

It’s not this that makes Baumgartner feel incomplete so much as the fact that any of its threads might have been expanded into a full-length novel. Maybe Auster had various projects on the go at the time of his final illness and combined them. That could explain the mishmash. I also had the odd sense that there were unconscious pastiches of other authors. Baumgartner reminds me a lot of James Darke, the curmudgeonly widower in Rick Gekoski’s pair of novels. When Baumgartner speaks to his dead wife on the telephone, I went hunting through my notes because I knew I’d encountered that specific plot before (the short story “The Telephone” by Mary Treadgold, collected in Fear, edited by Roald Dahl). The Ukraine passage might have come from Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer. So, for me, this was less distinctive as Auster works go. However, it’s gently readable and not formally challenging so it’s a pleasant valedictory volume if not the best representative of his oeuvre. (Public library) ![]()

Travels in the Scriptorium (2006)

This is very much in the vein of The Locked Room and Oracle Night and indeed makes reference to characters from those earlier books (Sophie Fanshawe and Peter Stillman from the former; John Trause from the latter). Mr. Blank lives in a sparse room containing manuscript pages and a stack of photographs. He is tended by a nurse named Anna Blume and given a rainbow of pharmaceuticals. Whether the pills help or keep him pacified is unclear. The haziness of his memory could be due to age or the drugs. He receives various visitors he feels he should recognize but can’t, and from the comments they make he fears he is being punished for dangerous missions he spearheaded. Even Anna, object of his pitiable sexual desires, is somehow his moral superior. Everyday self-care is struggle enough for him, but he does end up reading and adding to the partial stories on the table, including a dark Western set in an alternative 19th-century USA. Whatever he’s done in the past, he’s now an imprisoned writer and this is a day in his newly constrained life. The novella is a deliberate assemblage of typical Auster tropes and characters; there’s a puppet-master here, but no point. An indulgent minor work. But that’s okay as I still have plenty of appealing books from his back catalogue to read. [Interestingly, the American cover has a white horse in the centre of the room, an embodiment of Mr. Blank’s childhood memory of a white rocking-horse he called Whitey.] (Public library)

This is very much in the vein of The Locked Room and Oracle Night and indeed makes reference to characters from those earlier books (Sophie Fanshawe and Peter Stillman from the former; John Trause from the latter). Mr. Blank lives in a sparse room containing manuscript pages and a stack of photographs. He is tended by a nurse named Anna Blume and given a rainbow of pharmaceuticals. Whether the pills help or keep him pacified is unclear. The haziness of his memory could be due to age or the drugs. He receives various visitors he feels he should recognize but can’t, and from the comments they make he fears he is being punished for dangerous missions he spearheaded. Even Anna, object of his pitiable sexual desires, is somehow his moral superior. Everyday self-care is struggle enough for him, but he does end up reading and adding to the partial stories on the table, including a dark Western set in an alternative 19th-century USA. Whatever he’s done in the past, he’s now an imprisoned writer and this is a day in his newly constrained life. The novella is a deliberate assemblage of typical Auster tropes and characters; there’s a puppet-master here, but no point. An indulgent minor work. But that’s okay as I still have plenty of appealing books from his back catalogue to read. [Interestingly, the American cover has a white horse in the centre of the room, an embodiment of Mr. Blank’s childhood memory of a white rocking-horse he called Whitey.] (Public library)![]()

Faber, Auster’s longtime publisher, counts towards Reading Independent Publishers Month.

R.I.P. Reads: Dahl, Le Guin, Lessing, Paver

This is my second year participating in R.I.P. – Readers Imbibing Peril, now in its 14th year. I assembled a lovely pile of magical or spooky reads to last me through October and noticed they were almost all by women, so I decided to make it an all-female challenge (yes, even with a Dahl title – see below) this year. I’m in the middle of another book and have a few more awaiting me, but with just two weeks left in the month I don’t know if I’ll manage to follow up this post with a Part II. At any rate, these first four were solid selections: classic ghost stories, children’s fantasy, a horror novella about an evil child, and an Arctic chiller.

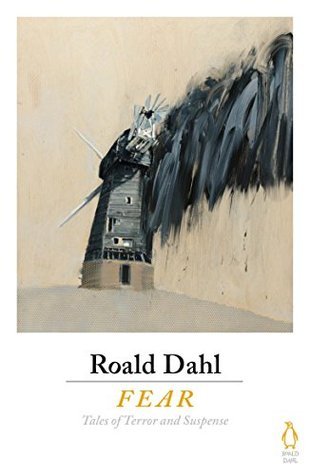

Fear: Tales of Terror and Suspense (selected by Roald Dahl) (2017)

“Spookiness is, after all, the real purpose of the ghost story. It should give you the creeps and disturb your thoughts.”

I was sent this selection of Dahl-curated ghost stories as part of a book bundle in advance of a blog tour for Roald Dahl Day last year. For now I’ve read just the five stories by women, and will polish off the rest next year.

This collection originated from a television series on ghost stories that Dahl proposed for the American market in 1958 (the pilot was poorly received and it never got made). For his research he read nearly 750 ghost stories and whittled them down to the top 24. Women authors dominated early on in the selection process, but by the end the genders came out nearly even, with 13 men and 11 women. It’s disappointing, then, that only five of the 14 stories included here are by women – one of whom gets two entries, so there’s just four female authors recognized. And this even though Dahl claims that, when it comes to ghost stories, “it is the women who have written some of the very best ones.”

This collection originated from a television series on ghost stories that Dahl proposed for the American market in 1958 (the pilot was poorly received and it never got made). For his research he read nearly 750 ghost stories and whittled them down to the top 24. Women authors dominated early on in the selection process, but by the end the genders came out nearly even, with 13 men and 11 women. It’s disappointing, then, that only five of the 14 stories included here are by women – one of whom gets two entries, so there’s just four female authors recognized. And this even though Dahl claims that, when it comes to ghost stories, “it is the women who have written some of the very best ones.”

Any road, these are the five stories I read, all of which I found suitably creepy, though the Wharton is overlong. Each one pivots on a moment when the narrator realizes that a character they have been interacting with is actually dead. Even if you’ve seen the twist coming, there’s still a little clench of the heart when you have it confirmed by a third party.

“Harry” and “Christmas Meeting” by Rosemary Timperley: A little girl who survived a murder attempt is reclaimed by her late brother; a woman meets a century-dead author one lonely holiday – I liked that in this one each character penetrates the other’s time period.

“The Corner Shop” by Cynthia Asquith: An inviting antique shop is run by two young women during the day, but by a somber old man in the evenings. He likes to give his customers a good deal to atone for his miserly actions of the past.

“The Telephone” by Mary Treadgold: A man continues communicating with his dead ex-wife via the phone line.

“Afterward” by Edith Wharton: An American couple settles in a home in Dorset, and the husband disappears, after a dodgy business deal, in the company of a mysterious stranger.

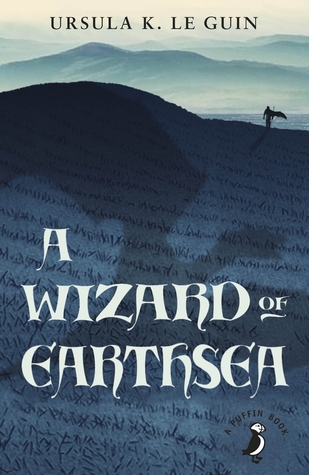

A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin (1968)

This was my second attempt with the late Le Guin, who would be turning 90 on the 21st; I didn’t get far at all with a buddy read of The Left Hand of Darkness last year. I enjoyed this a fair bit more, perhaps because it’s meant for children – I reckon I would have liked it most when I was ages nine to 11 and obsessed with various series of fantasy novels featuring dragons.

This was my second attempt with the late Le Guin, who would be turning 90 on the 21st; I didn’t get far at all with a buddy read of The Left Hand of Darkness last year. I enjoyed this a fair bit more, perhaps because it’s meant for children – I reckon I would have liked it most when I was ages nine to 11 and obsessed with various series of fantasy novels featuring dragons.

Long before Harry Potter was a glimmer, this was the archetypal story of a boy wizard learning magic at school. Ged meets many cryptic mentors and realizes that naming a thing gives you power over it. In his rivalry with the other boys, he accidentally releases a shadow beast and has to try to gain back control of it. It’s slightly difficult to keep on top of all the names and places (Le Guin created a whole archipelago, which you can see in the opening map) and I found my interest waning after the halfway point, but I did love the scene of Ged fighting with a dragon.

A favorite passage: “But you must not change one thing, one pebble, one grain of sand, until you know what good and evil will follow on the act. … A wizard’s power of Changing and of Summoning can shake the balance of the world.”

The Fifth Child by Doris Lessing (1988)

Shelve this alongside We Need to Talk about Kevin as a book to make you rethink having kids. Harriet and David Lovatt buy a large Victorian house within commuting distance of London and dream of filling it with children – six, eight; however many. Their first four children are all they’d hoped for, if not spaced out as much as they intended. The Lovatts enjoy hosting the extended family at Easter and Christmas and during the summer holidays. Although there are good-natured jokes about the couple’s fertility, everyone enjoys the cozy, bustling atmosphere. “The Lovatts were a happy family. It was what they had chosen and what they deserved.”

[MILD SPOILERS ENSUE]

Everything changes with pregnancy #5, which is different right from the off. This “savage thing inside her” is kicking Harriet black and blue from the inside and grown to full term by eight months. When Ben is born Harriet thinks, “He’s like a troll, or a goblin.” Like a succubus, he sucks her dry, biting her nipples black and blue; he screams and thrashes non-stop; he’s freakishly strong and insatiably hungry. He strangles house pets and eats a raw chicken with his bare hands. Although he learns basic language and social skills from watching his older siblings and mimicking his idols from a motorcycle gang, something in him is not human. Yet Harriet cannot bear to leave Ben to rot in an institution.

Everything changes with pregnancy #5, which is different right from the off. This “savage thing inside her” is kicking Harriet black and blue from the inside and grown to full term by eight months. When Ben is born Harriet thinks, “He’s like a troll, or a goblin.” Like a succubus, he sucks her dry, biting her nipples black and blue; he screams and thrashes non-stop; he’s freakishly strong and insatiably hungry. He strangles house pets and eats a raw chicken with his bare hands. Although he learns basic language and social skills from watching his older siblings and mimicking his idols from a motorcycle gang, something in him is not human. Yet Harriet cannot bear to leave Ben to rot in an institution.

At first I wondered if this was a picture of an extremely autistic child, but Lessing makes the supernatural element clear. “We are being punished,” Harriet says to David. “For presuming … we could be happy.” I think I was waiting for a few more horrific moments and a climactic ending, whereas Lessing almost normalizes Ben, making him part of a gang of half-feral youths who rampage around late-1980s Britain (and she took up his story in a sequel, Ben in the World). But I raced through this in just a few days and enjoyed the way dread overlays the fable-like simplicity of the family’s early life.

Dark Matter: A Ghost Story by Michelle Paver (2010)

I read Paver’s Thin Air as part of last year’s R.I.P. challenge and it was very similar: a 1930s setting, an all-male adventure, an extreme climate (in that case: the Himalayas). Most of Dark Matter is presented as a journal written by Jack Miller, a lower-class lad who wanted to become a physicist but had to make a living as a clerk instead. He feels he doesn’t truly belong among the wealthier chaps on this Arctic expedition, but decides this is his big chance and he’s not going to give it up.

I read Paver’s Thin Air as part of last year’s R.I.P. challenge and it was very similar: a 1930s setting, an all-male adventure, an extreme climate (in that case: the Himalayas). Most of Dark Matter is presented as a journal written by Jack Miller, a lower-class lad who wanted to become a physicist but had to make a living as a clerk instead. He feels he doesn’t truly belong among the wealthier chaps on this Arctic expedition, but decides this is his big chance and he’s not going to give it up.

Even as the others drop out due to bereavement and illness, he stays the course, continuing to gather meteorological data and radio it back to England from this bleak settlement in the far north of Norway. For weeks his only company is a pack of sled dogs, and his grasp on reality becomes shaky as he begins to be visited by the ghost of a trapper who was tortured to death nearby – “the one who walks again.” Paver’s historical thrillers are extremely readable. I tore through this, yet never really found it scary.

Note: This book is the subject of the Bookshop Band song “Steady On” (video here).

And, alas, three DNFs:

The Wych Elm by Tana French – French writes really fluid prose and inhabits the mind of a young man with admirable imagination. I read the first 100 pages and skimmed another 50 and STILL hadn’t gotten to the main event the blurb heralds: finding a skull in the wych elm in the garden at Ivy House. I kept thinking, “Can we get on with it? Let’s cut to the chase!” I have had French’s work highly recommended so may well try her again.

The Wych Elm by Tana French – French writes really fluid prose and inhabits the mind of a young man with admirable imagination. I read the first 100 pages and skimmed another 50 and STILL hadn’t gotten to the main event the blurb heralds: finding a skull in the wych elm in the garden at Ivy House. I kept thinking, “Can we get on with it? Let’s cut to the chase!” I have had French’s work highly recommended so may well try her again.

The Hoarder by Jess Kidd – Things in Jars was terrific; I thought Kidd’s back catalogue couldn’t fail to draw me in. This was entertaining enough that I made it to page 152, if far too similar to Jars (vice versa, really, as this came first; ghosts/saints only the main character sees; a transgender landlady/housekeeper); I then found that picking it back up didn’t appeal at all. Maud Drennan is a carer to a grumpy giant of a man named Cathal Flood whose home is chock-a-block with stuff. What happened to his wife? And to Maud’s sister? Who cares!

The Hoarder by Jess Kidd – Things in Jars was terrific; I thought Kidd’s back catalogue couldn’t fail to draw me in. This was entertaining enough that I made it to page 152, if far too similar to Jars (vice versa, really, as this came first; ghosts/saints only the main character sees; a transgender landlady/housekeeper); I then found that picking it back up didn’t appeal at all. Maud Drennan is a carer to a grumpy giant of a man named Cathal Flood whose home is chock-a-block with stuff. What happened to his wife? And to Maud’s sister? Who cares!

The Silent Companions by Laura Purcell – Purcell is now on her third Gothic novel in three years. I had a stab at her first and it was distinctly okay. I read the first 24 pages and skimmed to p. 87. Reminiscent of The Shadow Hour, The Familiars, etc.

The Silent Companions by Laura Purcell – Purcell is now on her third Gothic novel in three years. I had a stab at her first and it was distinctly okay. I read the first 24 pages and skimmed to p. 87. Reminiscent of The Shadow Hour, The Familiars, etc.