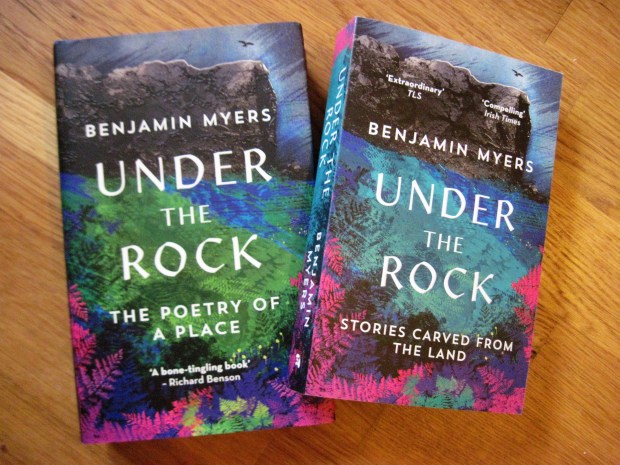

Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers: Paperback Giveaway

Benjamin Myers’s Under the Rock was my nonfiction book of 2018, so I’m delighted to be kicking off the blog tour for its paperback release on the 25th (with a new subtitle, “Stories Carved from the Land”). I’m reprinting my Shiny New Books review below, with permission, and on behalf of Elliott & Thompson I am also hosting a giveaway of a copy of the paperback. Leave a comment saying that you’d like to win and I will choose one entry at random at the end of the day on Tuesday the 30th. (Sorry, UK only.)

My review:

Benjamin Myers has been having a bit of a moment. In 2017 Bluemoose Books published his fifth novel, The Gallows Pole, which went on to win the Roger Deakin Award and the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction and is now on its fourth printing. This taste of fame has brought renewed attention to his earlier work, including Beastings (2014), recipient of the Northern Writers’ Award. I’ve been interested in Myers’s work ever since I read an extract from the then-unpublished The Gallows Pole in Autumn, the Wildlife Trusts anthology edited by Melissa Harrison, but this is the first of his books that I’ve managed to read.

“Unremarkable places are made remarkable by the minds that map them,” Myers writes, and that is certainly true of Scout Rock, a landmark overlooking Mytholmroyd, near where the author lives in the Calder Valley of West Yorkshire. When he moved up there from London over a decade ago, he and his wife lived in a rental cottage built in 1640. He approached his new patch with admirable curiosity, and supplemented the observations he made from his study window with frequent long walks with his dog, Heathcliff (“Walking is writing with your feet”), and research into the history of the area. The result is a divagating, lyrical book that ranges from geology to true crime but has an underlying autobiographical vein.

Ted Hughes was born nearby, the Brontës not that much further away, and Hebden Bridge, in particular, has become a bastion of avant-garde artists and musicians. Myers also gets plenty of mileage out of his eccentric neighbours and postman. It’s a town that seems to attract oddballs and renegades, from the vigilantes who poisoned the fishing hole to an overdose victim who turns up beneath a stand of Himalayan balsam. A strange preponderance of criminals has come from the region, too, including sexual offenders like Jimmy Savile and serial killers such as the Yorkshire Ripper and Harold Shipman (‘Doctor Death’).

On his walks Myers discovers the old town tip, still full of junk that won’t biodegrade for hundreds more years, and finds traces of the asbestos that was dumped by Acre Mill, creating a national scandal. This isn’t old-style nature writing in search of a few remaining unspoiled places. Instead, it’s part of a growing literary interest in the ‘edgelands’ between settlement and the wild – places where the human impact is undeniable but nature is creeping back in. (Other recent examples would be Common Ground by Rob Cowen, Landfill by Tim Dee, Edgelands by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, and Outskirts by John Grindrod.)

Under the Rock gives a keen sense of the seasons’ change and the seemingly inevitable melancholy that accompanies bad weather. A winter of non-stop rain left Myers nigh on delirious with flu; Storm Eva caused the Calder River to flood. He was a part of the effort to rescue trapped pensioners. Heartening as it is to see how the disaster brought people together – Sikh and Muslim charities and Syrian refugees were among the first to help – looting also resulted. One of the most remarkable things about this book is how Myers takes in such extremes of behaviour, along with mundanities, and makes them all part of a tapestry of life.

The book’s recurring themes tangle through all of the sections, even though it has been given a somewhat arbitrary four-part structure (Wood – Earth – Water – Rock). Interludes between these major parts transcribe Myers’s field notes, which are more like impromptu poems that he wrote in a notebook kept in his coat pocket. The artistry of these snippets of poetry is incredible given that they were written in situ, and their alliteration bleeds into his prose as well. My favourite of the poems was “On Lighting the First Fire”:

Autumn burns

the sky

the woods

the valley

death is everywhere

but beneath

the golden cloak

the seeds of

a summer’s

dreaming still sing.

The Field Notes sections are illustrated with Myers’s own photographs, which, again, are of enviable quality. I came away from this feeling like Myers could write anything – a thank-you note, a shopping list – and make it read as profound literature. Every sentence is well-crafted and memorable. There is also a wonderful sense of rhythm to his pages, with a pithy sentence appearing every couple of paragraphs to jolt you to attention.

“Writing is a form of alchemy,” Myers declares. “It’s a spell, and the writer is the magician.” I certainly fell under the author’s spell here. While his eyes are open to the many distressing political and environmental changes of the last few years, the ancient perspective of the Rock reminds him that, though humans are ultimately insignificant and individual lives are short, we can still rejoice in our experiences of the world’s beauty while we’re here.

From the publisher:

“Benjamin Myers was born in Durham in 1976. He is a prize-winning author, journalist and poet. His recent novels are each set in a different county of northern England, and are heavily inspired by rural landscapes, mythology, marginalised characters, morality, class, nature, dialect and post-industrialisation. They include The Gallows Pole, winner of the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction, and recipient of the Roger Deakin Award; Turning Blue, 2016; Beastings, 2014 (Portico Prize for Literature & Northern Writers’ Award winner), Pig Iron, 2012 (Gordon Burn Prize winner & Guardian Not the Booker Prize runner-up); and Richard, a Sunday Times Book of the Year 2010. Bloomsbury will publish his new novel, The Offing, in August 2019.

As a journalist, he has written widely about music, arts and nature. He lives in the Upper Calder Valley, West Yorkshire, the inspiration for Under the Rock.”

Recent Poetry Reads

I love interspersing poetry with my other reading, and this year it seems like I’m getting to more of it than ever. Although I try to have a poetry collection on the go at all times, I still consider myself a novice and enjoy discovering new-to-me poets. However, I know many readers who totally avoid poetry because they assume they won’t understand it or it would feel too much like hard work.

Sinking into poems is certainly a very different experience from opening up a novel or a nonfiction narrative. Often I read parts of a poem two or three times – to make sure I’ve taken it in properly, or just to savor the language. I try to hear the lines aloud in my head so I can appreciate the sonic techniques at work, whether rhyming or alliteration. Reading or listening to poetry engages a different part of the brain, and it may be best to experience it in something of a dreamlike state.

I hope you’ll find a book or two that appeals from the selection below.

Thousandfold by Nina Bogin (2019)

This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds – along with their eggs and feathers – are a frequent presence. Often a particular object will serve as a totem as the poet remembers the most important people in her life: her father’s sheepskin coat, her grandmother’s pink bathrobe, and the slippers her late husband shuffled around in – a sign of how diminished he’d become due to dementia. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature. I’d recommend this to fans of Linda Pastan.

This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds – along with their eggs and feathers – are a frequent presence. Often a particular object will serve as a totem as the poet remembers the most important people in her life: her father’s sheepskin coat, her grandmother’s pink bathrobe, and the slippers her late husband shuffled around in – a sign of how diminished he’d become due to dementia. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature. I’d recommend this to fans of Linda Pastan.

My rating:

Thousandfold will be published by Carcanet Press on January 31st. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Sweet Shop by Amit Chaudhuri (2019)

I was previously unfamiliar with Chaudhuri’s work, and unfortunately this insubstantial book about his beloved Indian places and foods hasn’t lured me into trying any more. The one poem I liked best was “Creek Row,” about a Calcutta lane used as a shortcut: “you are a thin, short-lived, / decaying corridor” and an “oesophageal aperture”. I also liked, as stand-alone lines go, “Refugees are periodic / like daffodils.” Nothing else stood out for me in terms of language, sound or theme. Poetry is so subjective; all I can say is that some poets will click with you and others don’t. In any case, the atmosphere is similar to what I found in Korma, Kheer and Kismet: Five Seasons in Old Delhi by Pamela Timms.

I was previously unfamiliar with Chaudhuri’s work, and unfortunately this insubstantial book about his beloved Indian places and foods hasn’t lured me into trying any more. The one poem I liked best was “Creek Row,” about a Calcutta lane used as a shortcut: “you are a thin, short-lived, / decaying corridor” and an “oesophageal aperture”. I also liked, as stand-alone lines go, “Refugees are periodic / like daffodils.” Nothing else stood out for me in terms of language, sound or theme. Poetry is so subjective; all I can say is that some poets will click with you and others don’t. In any case, the atmosphere is similar to what I found in Korma, Kheer and Kismet: Five Seasons in Old Delhi by Pamela Timms.

My rating:

My thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

Windfall by Miriam Darlington (2008)

Before I picked this up from the bookstall at the New Networks for Nature conference in November, I had no idea that Darlington had written poetry before she turned to nature writing (Otter Country and Owl Sense). These poems are rooted in the everyday: flipping pancakes, sitting down to coffee, tending a garden, smiling at a dog. Multiple poems link food and erotic pleasure; others make nature the source of exaltation. I loved her descriptions of a heron (“a standing stone / perched in silt / a wrap of grey plumage”) and a blackbird (“the first bird / a glockenspiel in C / an improvisation on morning / a blue string of notes”), Lots of allusions and delicious alliteration. Pick this up if you’re missing Mary Oliver.

Before I picked this up from the bookstall at the New Networks for Nature conference in November, I had no idea that Darlington had written poetry before she turned to nature writing (Otter Country and Owl Sense). These poems are rooted in the everyday: flipping pancakes, sitting down to coffee, tending a garden, smiling at a dog. Multiple poems link food and erotic pleasure; others make nature the source of exaltation. I loved her descriptions of a heron (“a standing stone / perched in silt / a wrap of grey plumage”) and a blackbird (“the first bird / a glockenspiel in C / an improvisation on morning / a blue string of notes”), Lots of allusions and delicious alliteration. Pick this up if you’re missing Mary Oliver.

My rating:

A Responsibility to Awe by Rebecca Elson (2018)

Elson, an astronomer who worked on the Hubble Space Telescope, died of breast cancer; this is a reprint of her posthumous 2001 publication. Along with a set of completed poems, the volume includes an autobiographical essay and extracts from her notebooks. Her impending mortality has a subtle presence in the book. I focused on the finished poems, which take their metaphors from physics (“Dark Matter”), mathematics (“Inventing Zero”) and evolution (indeed, “Evolution” was my favorite). In the essay that closes the book, Elson remembers long summers of fieldwork and road trips across Canada with her geologist father (I was reminded of Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye), and traces her academic career as she bounced between the United States and Great Britain.

Elson, an astronomer who worked on the Hubble Space Telescope, died of breast cancer; this is a reprint of her posthumous 2001 publication. Along with a set of completed poems, the volume includes an autobiographical essay and extracts from her notebooks. Her impending mortality has a subtle presence in the book. I focused on the finished poems, which take their metaphors from physics (“Dark Matter”), mathematics (“Inventing Zero”) and evolution (indeed, “Evolution” was my favorite). In the essay that closes the book, Elson remembers long summers of fieldwork and road trips across Canada with her geologist father (I was reminded of Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye), and traces her academic career as she bounced between the United States and Great Britain.

My rating:

My thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

These next two were on the Costa Prize for Poetry shortlist, along with Hannah Sullivan’s Three Poems, which was one of my top poetry collections of 2018 and recently won the T. S. Eliot Prize. I first encountered the work of all three poets at last year’s Faber Spring Party.

Us by Zaffar Kunial (2018)

Many of these poems are about split loyalties and a composite identity – Kunial’s father was Kashmiri and his mother English – and what the languages we use say about us. He also writes about unexpectedly developing a love for literature, and devotes one poem to Jane Austen and another to Shakespeare. My favorites were “Self Portrait as Bottom,” about doing a DNA test (“O I am translated. / The speech of numbers. / Here’s me in them / and them in me. … What could be more prosaic? / I am split. 50% Europe. / 50% Asia.”), and the title poem, a plea for understanding and common ground.

Many of these poems are about split loyalties and a composite identity – Kunial’s father was Kashmiri and his mother English – and what the languages we use say about us. He also writes about unexpectedly developing a love for literature, and devotes one poem to Jane Austen and another to Shakespeare. My favorites were “Self Portrait as Bottom,” about doing a DNA test (“O I am translated. / The speech of numbers. / Here’s me in them / and them in me. … What could be more prosaic? / I am split. 50% Europe. / 50% Asia.”), and the title poem, a plea for understanding and common ground.

My rating:

Soho by Richard Scott (2018)

When I saw him live, Scott read two of the amazingly intimate poems from this upcoming collection. One, “cover-boys,” is about top-shelf gay porn and what became of the models; the other, “museum,” is, on the face of it, about mutilated sculptures of male bodies in the Athens archaeological museum, but also, more generally, about “the vulnerability of / queer bodies.” If you appreciate the erotic verse of Mark Doty and Andrew McMillan, you need to pick this one up immediately. Scott channels Verlaine in a central section of gritty love poems and Whitman in the final, multi-part “Oh My Soho!”

When I saw him live, Scott read two of the amazingly intimate poems from this upcoming collection. One, “cover-boys,” is about top-shelf gay porn and what became of the models; the other, “museum,” is, on the face of it, about mutilated sculptures of male bodies in the Athens archaeological museum, but also, more generally, about “the vulnerability of / queer bodies.” If you appreciate the erotic verse of Mark Doty and Andrew McMillan, you need to pick this one up immediately. Scott channels Verlaine in a central section of gritty love poems and Whitman in the final, multi-part “Oh My Soho!”

My rating:

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith (2017)

Like Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, this is a book whose aims I can admire even though I didn’t particularly enjoy reading it. It’s about being black and queer in an America where both those identifiers are dangerous, where guns and HIV are omnipresent threats. “reader, what does it / feel like to be safe? white?” Smith asks. “when i was born, i was born a bull’s-eye.” The narrator and many of the other characters are bruised and bloody, with blood used literally but also metaphorically for kinship and sexual encounters. By turns tender and biting, exultant and uncomfortable, these poems are undeniably striking, and a necessary wake-up call for readers who may never have considered the author’s perspective.

Like Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, this is a book whose aims I can admire even though I didn’t particularly enjoy reading it. It’s about being black and queer in an America where both those identifiers are dangerous, where guns and HIV are omnipresent threats. “reader, what does it / feel like to be safe? white?” Smith asks. “when i was born, i was born a bull’s-eye.” The narrator and many of the other characters are bruised and bloody, with blood used literally but also metaphorically for kinship and sexual encounters. By turns tender and biting, exultant and uncomfortable, these poems are undeniably striking, and a necessary wake-up call for readers who may never have considered the author’s perspective.

My rating:

Up next: This Pulitzer-winning collection from the late Mary Oliver, whose work I’ve had mixed success with before (Dream Work is by far her best that I’ve read so far). We lost two great authors within a week! RIP Diana Athill, too, who was 101.

Any recent poetry reads you can recommend to me?

A Patroness of the Arts

I recently sponsored my first book via Unbound, the UK’s crowdfunding publisher. You’re probably familiar with some Unbound titles even if that name doesn’t ring a bell. For instance, you might remember that The Wake by Paul Kingsnorth, an Unbound title from 2014, became the first crowdfunded novel longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. I’ve reviewed another previous Unbound title, Martine McDonagh’s Narcissism for Beginners, and will be participating in the blog tour for Lev Parikian’s Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? in May.

The forthcoming title I’ve chosen to support is Women on Nature by Katharine Norbury, which promises to be a wide-ranging and learned anthology celebrating the tradition of women’s writing about nature (both fiction and non-). I enjoyed Norbury’s first book, The Fish Ladder, which is a memoir in the vein of H Is for Hawk, and also saw her speak at the New Networks for Nature conference in 2016.

The forthcoming title I’ve chosen to support is Women on Nature by Katharine Norbury, which promises to be a wide-ranging and learned anthology celebrating the tradition of women’s writing about nature (both fiction and non-). I enjoyed Norbury’s first book, The Fish Ladder, which is a memoir in the vein of H Is for Hawk, and also saw her speak at the New Networks for Nature conference in 2016.

Albums that exist because I helped crowdfund them.

I’d only ever crowdfunded music before – albums by The Bookshop Band, Krista Detor, Duke Special and Marc Martel. Beaming internally at feeling like a patroness of the arts after funding my Women on Nature hardback, I kept the smug glow going by signing up to support The Bookshop Band via Patreon (where you can commit to a certain amount per creation, e.g. per music video, and have the option of setting a monthly cap) and to fund an album by their singer/cellist Beth Porter and her band The Availables via Indiegogo.

Have you ever gotten involved in a crowdfunding project? How about for the arts?

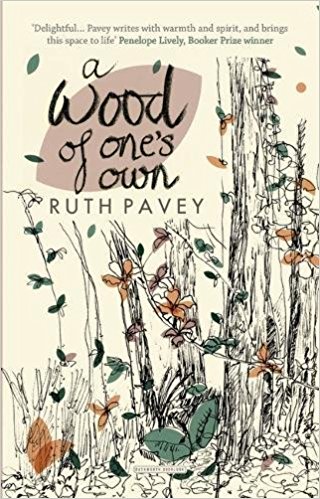

A Wood of One’s Own by Ruth Pavey

In 1999 Ruth Pavey bought four acres of Somerset scrubland at a land auction. It wasn’t exactly what she’d set out to acquire: it wasn’t a “pretty” field, and traffic was audible from it. But she was pleased to return to her family’s roots in the Somerset Levels area – this “silted place of slow waters, eels, reeds, drainage engineers, buttercups, church towers, quiet” that her father came from, and where she was born – and she fancied planting some trees.

There never was a master plan […] I wanted to open up enough room for trees that might live for centuries […] I also wanted to keep areas of wilderness for the creatures […] And I wanted it to be beautiful. Not immaculate, that was too much to hope for, but, in its own ragged, benign way, beautiful.

This pleasantly meandering memoir, Pavey’s first book, is an account of nearly two decades spent working alongside nature to restore some of her land to orchard and maintain the rest in good health. The first steps were clear: she had to deal with some fallen willows, find a water source and plan a temporary shelter. Rather than a shed, which would be taken as evidence of permanent residency, she resorted to a “Rollalong,” a mobile metal cabin she could heat just enough to survive nights spent on site. Before long, though, she bought a nearby cottage to serve as her base when she left her London teaching job behind on weekends.

This pleasantly meandering memoir, Pavey’s first book, is an account of nearly two decades spent working alongside nature to restore some of her land to orchard and maintain the rest in good health. The first steps were clear: she had to deal with some fallen willows, find a water source and plan a temporary shelter. Rather than a shed, which would be taken as evidence of permanent residency, she resorted to a “Rollalong,” a mobile metal cabin she could heat just enough to survive nights spent on site. Before long, though, she bought a nearby cottage to serve as her base when she left her London teaching job behind on weekends.

Then came the hard work: after buying trees from nurseries and ordering apple varieties that would fruit quickly, Pavey had to plant it all and pick up enough knowledge about pruning, grafting, squirrel management, canker and so on to keep everything alive. There was always something new to learn, and plenty of surprises – such as the stray llama that visited her neighbor’s orchard. Local history weaves through this story, too: everything from the English Civil War to Cecil Sharp’s collecting of folk songs.

Britain has seen a recent flourishing of hybrid memoirs–nature books by the likes of Helen Macdonald, Mallachy Tallack and Clover Stroud. By comparison, Pavey is not as confiding about her personal life as you might expect. She reveals precious little about herself: she tells us that her mother died when she was young and she was mostly raised by an aunt; she hints at some failed love affairs; in the acknowledgments she mentions a son; from the jacket copy I know she’s the gardening correspondent for the Hampstead & Highgate Express. But that’s it. This really is all about the wood, and apart from serving as an apt Woolf reference the use of “one” in the title is in deliberate opposition to the confessional connotations of “my”.

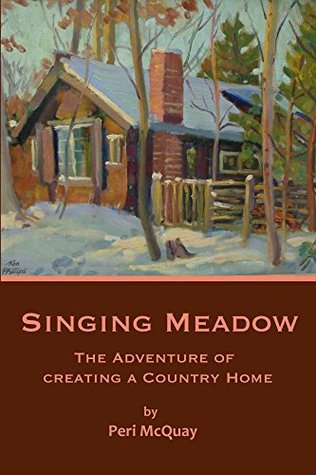

Still, I think this book will appeal to readers of modern nature writers like Paul Evans and Mark Cocker – these two are Guardian Country Diarists, and Pavey develops the same healthy habit of sticking to one patch and lovingly monitoring its every development. I was also reminded of Peri McQuay’s memoir of building a home in the woods of Canada.

Still, I think this book will appeal to readers of modern nature writers like Paul Evans and Mark Cocker – these two are Guardian Country Diarists, and Pavey develops the same healthy habit of sticking to one patch and lovingly monitoring its every development. I was also reminded of Peri McQuay’s memoir of building a home in the woods of Canada.

What struck me most was how this undertaking encourages the long view: “being finished, in the sense of being brought to a satisfactory conclusion, is not something that happens in a garden, an orchard or a wood, however well planned or cultivated,” she writes. It’s an ongoing project, and she avoids nostalgia and melodrama in planning for its future after she’s gone; “I am only there for a while, a twinkling. But [the trees and creatures] … will remain.” This would make a good Christmas present for the dedicated gardener in your life, not least because of the inclusion of Pavey’s lovely black-and-white line drawings.

A Wood of One’s Own was published on September 21st by Duckworth Overlook. My thanks to the publisher for a free copy for review.

My rating:

Finding a Home in Nature: Singing Meadow by Peri McQuay

For 30 years Peri McQuay and her family lived in the idyllic 700-strong village of Westport in Eastern Ontario. Her husband, Barry, was the park supervisor at Foley Mountain Conservation Area, the subject of her first nature-themed memoir, The View from Foley Mountain (1995), and they lived on site amid its 800 acres. The constant push to engage in fundraising gradually made it a less pleasant place to live and work, so as Barry’s retirement neared they knew it was time to find a new home of their own. That quest is the subject of her third book, Singing Meadow: The Adventure of Creating a Country Home.

McQuay fantasized about a farmhouse surrounded by 50–100 acres of their own land, but was aware that their limited finances might not stretch to match their dreams. Long before they found their home they were buying little items for it, like an acorn door knocker that functioned as a reassuring totem object during the long, discouraging process of looking at houses. Over the course of two years, McQuay and her husband viewed more than 80 properties! Two pieces of advice they received turned out to be prescient: their loquacious real estate agent opined that “the house you end up in won’t be the one you set out to find,” and a woman in the doctor’s office waiting room counseled her, “don’t try too hard. It’ll happen when it’s time.”

In the end, they fell in love with a plot of land with a water meadow that was home to herons and beavers. With no handyman skills, they never thought they’d embark on building a home of their own. And as it turned out, finding the land was the easy bit, as opposed to the nitty-gritty details of designing what they wanted and meeting with builders who could make it a reality. But as they planted trees and looked ahead to their move in a year’s time, they were already forming a relationship with this place before the house was ever built, learning “the hard lessons of patience and possibility.”

In the end, they fell in love with a plot of land with a water meadow that was home to herons and beavers. With no handyman skills, they never thought they’d embark on building a home of their own. And as it turned out, finding the land was the easy bit, as opposed to the nitty-gritty details of designing what they wanted and meeting with builders who could make it a reality. But as they planted trees and looked ahead to their move in a year’s time, they were already forming a relationship with this place before the house was ever built, learning “the hard lessons of patience and possibility.”

Woven through the book are short flashbacks to other challenging times in McQuay’s life: having chronic fatigue syndrome in her 40s, her mother’s death a few years earlier, and a terrible ice storm at the park that left them without power for 17 days and caused damage to the forest that it might take 30 years to recover from. What all of these situations, as well as looking for a home, have in common is that they forced the author to take the long view, recognizing the healing effects of time rather than the tantalizing option of quick fixes.

I’ve never owned a home, but I’ve lived in 10 properties in the last 10 years. A lot of that nomadism has been foisted upon us rather than chosen, so I could relate to McQuay’s frustration throughout the property search, as well as her feelings of being uprooted – that “the very stuff of my life was being dismantled.” I can also see the wisdom of choosing the place that feeds your soul rather than the one that seems most convenient. She remembers one of the first properties she and Barry rented as a married couple: it was an old place with an outhouse and no running hot water, but they filled it with laughter and music and felt at peace there. It was infinitely better than any soulless town apartment they might have resorted to.

The book ends with a bit of a shocker, one of two moments that brought a lump to my throat. It’s a surprisingly bittersweet turn after what’s gone before, but it’s realistic and serves as a reminder that life is an ongoing story with sad moments we can’t prepare for.

Overall, this memoir reminds me most of Michael Pollan’s A Place of My Own (which appears in McQuay’s bibliography) and May Sarton’s journals, in which the search for a long-term home in Maine is a major element. Although this will appeal to people who like reading about women’s lives and transitions, I would particularly recommend it to readers of nature writing as the book is full of lovely passages like these:

It was bliss visiting the trees and caring for them. Each one was precious. Across the meadow I could see the black, white and yellow nesting bobolink plus an unidentifiable bird with a square seed-eating beak perched on a cattail. A crow flew by, checking to see what I was doing, then a blue jay. In the distance the newly returned yellow warbler was calling “witchetty witchetty.” Over and over, I needed to keep saying that I felt deep down, richly happy in the meadow. In the glassy eye of the pond, water was burbling up in such a powerful spilling-over that it chuckled musically. Indeed, while there was such a flow only the boldest, largest minnows could swim strongly enough to approach the rushing source.

Now I was walking slowly down to the water meadow, hearing the strange, quarrelsome-sounding talk of herons beginning another season here. I was teaching myself how to be aware every moment of every step so I could keep walking longer on this rough land. With any luck, this beloved place would be my last home. And, after the unignorable message of recent fierce summers, I was here to bear witness, to stand with the great maples, beeches, and oaks through whatever might come, to accompany with whatever grace I could for as long as I could sustain it. Living here, this was who I wanted to be—an old woman vanishing into the light.

I’m keen to get hold of McQuay’s other two books as well. Her work makes for very pleasant, meditative reading.

Note: The front cover is an oil painting of Peri’s childhood home by her artist father, Ken Phillips.

Singing Meadow: The Adventure of Creating a Country Home was published by Wintergreen Studios Press in 2016. My thanks to the author for sending a PDF copy for review.

My rating:

Face to Face: True stories of life, death and transformation from my career as a facial surgeon by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more. McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. Here he pulls back the curtain on the everyday details of his work life: everything from his footwear (white Crocs that soon become stained with blood and other fluids) to his musical choices (pop for the early phases; classical for the more challenging microsurgery stage). Like neurosurgeon Henry Marsh, he describes the awe of the first incision – “an almost overwhelming sense of entering into a sanctuary.” There’s a vicarious thrill to being let into this insider zone, and the book’s prose is perfectly clear and conversational, with unexpectedly apt metaphors such as “Sometimes the blood vessels can be of such poor quality that it is like trying to sew together two damp cornflakes.” This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve.

Face to Face: True stories of life, death and transformation from my career as a facial surgeon by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more. McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. Here he pulls back the curtain on the everyday details of his work life: everything from his footwear (white Crocs that soon become stained with blood and other fluids) to his musical choices (pop for the early phases; classical for the more challenging microsurgery stage). Like neurosurgeon Henry Marsh, he describes the awe of the first incision – “an almost overwhelming sense of entering into a sanctuary.” There’s a vicarious thrill to being let into this insider zone, and the book’s prose is perfectly clear and conversational, with unexpectedly apt metaphors such as “Sometimes the blood vessels can be of such poor quality that it is like trying to sew together two damp cornflakes.” This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve.  On Sheep: Diary of a Swedish Shepherd by Axel Lindén: Lindén left city life behind to take on his parents’ rural collective in southeast Sweden. This documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. Published diaries can devolve into tedium, but the brevity and selectiveness of this one prevent its accounts of everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling, as the shepherd practices being present with these “quiet and unpretentious and stoical” creatures. The attention paid to slaughtering and sustainability issues – especially as the business starts scaling up and streamlining activities – lends the book a wider significance. It is thus more realistic and less twee than its stocking-stuffer dimensions and jolly title font seem to suggest.

On Sheep: Diary of a Swedish Shepherd by Axel Lindén: Lindén left city life behind to take on his parents’ rural collective in southeast Sweden. This documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. Published diaries can devolve into tedium, but the brevity and selectiveness of this one prevent its accounts of everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling, as the shepherd practices being present with these “quiet and unpretentious and stoical” creatures. The attention paid to slaughtering and sustainability issues – especially as the business starts scaling up and streamlining activities – lends the book a wider significance. It is thus more realistic and less twee than its stocking-stuffer dimensions and jolly title font seem to suggest.

This is rather like a set of linked short stories, narrated by a home care aide who bathes and feeds those dying of AIDS. The same patients appear in multiple chapters titled “The Gift of…” (Sweat, Tears, Hunger, etc.) – Rick, Ed, Carlos, and Marty, with brief appearances from Mike and Keith. But for me the most poignant story was that of Connie Lindstrom, an old woman who got a dodgy blood transfusion after her mastectomy; the extra irony to her situation is that her son Joe is gay, and feels guilty because he thinks he should have been the one to get sick. Several characters move in and out of hospice care, and one building is so known for its AIDS victims that a savant resident greets the narrator with a roll call of its dead and dying. Brown herself had been a home-care worker, and she delivers these achingly sad vignettes in plain language that keeps the book from ever turning maudlin.

This is rather like a set of linked short stories, narrated by a home care aide who bathes and feeds those dying of AIDS. The same patients appear in multiple chapters titled “The Gift of…” (Sweat, Tears, Hunger, etc.) – Rick, Ed, Carlos, and Marty, with brief appearances from Mike and Keith. But for me the most poignant story was that of Connie Lindstrom, an old woman who got a dodgy blood transfusion after her mastectomy; the extra irony to her situation is that her son Joe is gay, and feels guilty because he thinks he should have been the one to get sick. Several characters move in and out of hospice care, and one building is so known for its AIDS victims that a savant resident greets the narrator with a roll call of its dead and dying. Brown herself had been a home-care worker, and she delivers these achingly sad vignettes in plain language that keeps the book from ever turning maudlin. Left over from my R.I.P. reading plans. This was nearly a one-sitting read for me: I read 94 pages in one go, though that may be because I was trapped under the cat. The first thing I noted was that the setup and dual timeframe are exactly the same as in Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered: we switch between the same place in 2016 and 1871. In this case it’s Wakewater House, a residential development by the Thames that incorporates the site of a dilapidated Victorian hydrotherapy center. After her partner cheats on her, Kirsten moves into Wakewater, where she’s alone apart from one neighbor, Manon, a hoarder who’s researching Anatomical Venuses – often modeled on prostitutes who drowned themselves in the river. In the historical strand, we see Wakewater through the eyes of Evelyn Byrne, who rescues street prostitutes and, after a disastrously ended relationship of her own, has arrived to take the Water Cure.

Left over from my R.I.P. reading plans. This was nearly a one-sitting read for me: I read 94 pages in one go, though that may be because I was trapped under the cat. The first thing I noted was that the setup and dual timeframe are exactly the same as in Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered: we switch between the same place in 2016 and 1871. In this case it’s Wakewater House, a residential development by the Thames that incorporates the site of a dilapidated Victorian hydrotherapy center. After her partner cheats on her, Kirsten moves into Wakewater, where she’s alone apart from one neighbor, Manon, a hoarder who’s researching Anatomical Venuses – often modeled on prostitutes who drowned themselves in the river. In the historical strand, we see Wakewater through the eyes of Evelyn Byrne, who rescues street prostitutes and, after a disastrously ended relationship of her own, has arrived to take the Water Cure. This was written yesterday, right? Actually, it was 55 years ago, but apart from the use of the word “Negro” you might have fooled me. Baldwin’s writing is still completely relevant, and eminently quotable. I can’t believe I hadn’t read him until now. This hard-hitting little book is composed of two essays that first appeared elsewhere. The first, “My Dungeon Shook,” a very short piece from the Madison, Wisconsin Progressive, is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation. No doubt it directly inspired Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me.

This was written yesterday, right? Actually, it was 55 years ago, but apart from the use of the word “Negro” you might have fooled me. Baldwin’s writing is still completely relevant, and eminently quotable. I can’t believe I hadn’t read him until now. This hard-hitting little book is composed of two essays that first appeared elsewhere. The first, “My Dungeon Shook,” a very short piece from the Madison, Wisconsin Progressive, is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation. No doubt it directly inspired Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. How to See Nature (1940), a quaint and perhaps slightly patronizing book by Shropshire naturalist and photographer Frances Pitt, was intended to help city evacuees cope with life in the countryside. Recently Pitt’s publisher, Batsford, commissioned Shropshire naturalist Paul Evans to revisit the topic. The result is a simply lovely volume (with a cover illustration by Angela Harding and black-and-white interior drawings by Evans’s partner, Maria Nunzia) that reflects on the range of modern relationships with nature and revels in the wealth of wildlife and semi-wild places we still have in Britain.

How to See Nature (1940), a quaint and perhaps slightly patronizing book by Shropshire naturalist and photographer Frances Pitt, was intended to help city evacuees cope with life in the countryside. Recently Pitt’s publisher, Batsford, commissioned Shropshire naturalist Paul Evans to revisit the topic. The result is a simply lovely volume (with a cover illustration by Angela Harding and black-and-white interior drawings by Evans’s partner, Maria Nunzia) that reflects on the range of modern relationships with nature and revels in the wealth of wildlife and semi-wild places we still have in Britain. Throughout, Evans treats issues like tree blight, climate change and species persecution with a light touch. Although it’s clear he’s aware of the diminished state of nature and quietly irate at how we are all responsible for pollution and invasive species, he writes lovingly and with poetic grace. I would not hesitate to recommend this to fans of contemporary nature writing.

Throughout, Evans treats issues like tree blight, climate change and species persecution with a light touch. Although it’s clear he’s aware of the diminished state of nature and quietly irate at how we are all responsible for pollution and invasive species, he writes lovingly and with poetic grace. I would not hesitate to recommend this to fans of contemporary nature writing. The book proper opens with a visit to

The book proper opens with a visit to

So I’m ambivalent about winter, and was interested to see how the authors collected in Melissa Harrison’s final seasonal anthology would explore its inherent contradictions. I especially appreciated the views of outsiders. Jini Reddy, a Quebec native, calls British winters “a long, grey sigh or a drawn-out ache.” In two of my favorite pieces, Christina McLeish and Nakul Krishna – from Australia and India, respectively – compare the warm, sunny winters they experienced in their homelands with their early experiences in Britain. McLeish remembers finding a disembodied badger paw on a frosty day during one of her first winters in England, while Krishna tells of a time he spent dogsitting in Oxford when all the students were on break. His decorous, timeless prose reminded me of J.R. Ackerley’s.

So I’m ambivalent about winter, and was interested to see how the authors collected in Melissa Harrison’s final seasonal anthology would explore its inherent contradictions. I especially appreciated the views of outsiders. Jini Reddy, a Quebec native, calls British winters “a long, grey sigh or a drawn-out ache.” In two of my favorite pieces, Christina McLeish and Nakul Krishna – from Australia and India, respectively – compare the warm, sunny winters they experienced in their homelands with their early experiences in Britain. McLeish remembers finding a disembodied badger paw on a frosty day during one of her first winters in England, while Krishna tells of a time he spent dogsitting in Oxford when all the students were on break. His decorous, timeless prose reminded me of J.R. Ackerley’s.