Catching Up on Prize Winners: Alderman, Grossman & Whitehead

Sometimes I love a prize winner and cheer the judges’ ruling; other times I shake my head and puzzle over how they could possibly think this was the best the year had to offer. I’m late to the party for these three recent prize-winning novels. I’m also a party pooper, I guess, because I didn’t particularly like or dislike a one of them. (Reviews are in the order in which I read the books. My rating for all three =  )

)

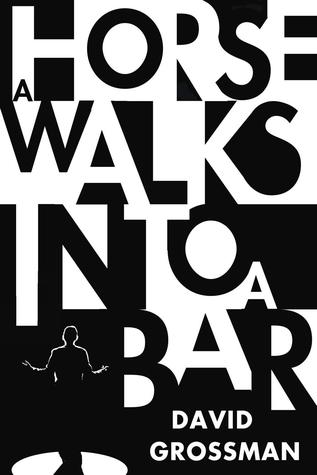

A Horse Walks into a Bar by David Grossman

(Winner of the Man Booker International Prize)

“Why the long face? Did someone die? It’s only stand-up comedy!” Except that for the comedian himself, Dovaleh Greenstein, this swan song of a show in the Israeli town of Netanya devolves into the story of the most traumatic day of his life. Grossman has made what seems to me an unusual choice of narrator: Avishai Lazar, a widower and Supreme Court justice, and Dov’s acquaintance from adolescence – they were in the same military training camp. Dov has invited him here to bear witness, and by the end we know Avishai will produce a written account of the evening.

“Why the long face? Did someone die? It’s only stand-up comedy!” Except that for the comedian himself, Dovaleh Greenstein, this swan song of a show in the Israeli town of Netanya devolves into the story of the most traumatic day of his life. Grossman has made what seems to me an unusual choice of narrator: Avishai Lazar, a widower and Supreme Court justice, and Dov’s acquaintance from adolescence – they were in the same military training camp. Dov has invited him here to bear witness, and by the end we know Avishai will produce a written account of the evening.

Although it could be said that Avishai’s asides about the past, and about the increasingly restive crowd in the club, give us a rest from Dov’s claustrophobic monologue, in doing so they break the spell. This would be more hard-hitting as a play or a short story composed entirely of speech; in one of those formats, Dov’s story might keep you spellbound through a single sitting. Instead, I found that I had to force myself to read even five or 10 pages at a time. There’s no doubt Grossman can weave a clever tale about loss, and there are actually some quite funny jokes in here too, but overall I found this significantly less powerful than the author’s previous work, Falling Out of Time.

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

(Winner of the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award and Arthur C. Clarke Award; longlisted for the Man Booker Prize)

Following Cora on her fraught journey from her Georgia plantation through the Carolinas and Tennessee to Indiana is enjoyable enough, with the requisite atrocities like lynchings and rapes thrown in to make sure it’s not just a picaresque cat-and-mouse battle between her and Arnold Ridgeway, the villainous slavecatcher. But I’m surprised that such a case has been made for the uniqueness of this novel based on a simple tweak of the historical record: Whitehead imagines the Underground Railroad as an actual subterranean transport system. This makes less of a difference than you might expect; if anything, it renders the danger Cora faces more abstract. The same might be said for the anachronistic combination of enlightened and harsh societies she passes through: by telescoping out to show the range of threats African-Americans faced between the Civil War and the 1930s, the novel loses immediacy.

Following Cora on her fraught journey from her Georgia plantation through the Carolinas and Tennessee to Indiana is enjoyable enough, with the requisite atrocities like lynchings and rapes thrown in to make sure it’s not just a picaresque cat-and-mouse battle between her and Arnold Ridgeway, the villainous slavecatcher. But I’m surprised that such a case has been made for the uniqueness of this novel based on a simple tweak of the historical record: Whitehead imagines the Underground Railroad as an actual subterranean transport system. This makes less of a difference than you might expect; if anything, it renders the danger Cora faces more abstract. The same might be said for the anachronistic combination of enlightened and harsh societies she passes through: by telescoping out to show the range of threats African-Americans faced between the Civil War and the 1930s, the novel loses immediacy.

Ultimately, I felt little attachment to Cora and had to force myself to keep plodding through her story. My favorite parts were little asides giving other characters’ backstories. There’s no doubt Whitehead can shape a plot and dot in apt metaphors (I particularly liked “Ajarry died in the cotton, the bolls bobbing around her like whitecaps on the brute ocean”). However, I kept thinking, Haven’t I read this story before? (Beloved, Ruby, The Diary of Anne Frank; seen on screen in Twelve Years a Slave, Roots and the like.) This is certainly capably written, but doesn’t stand out for me compared to Homegoing, which was altogether more affecting.

The Power by Naomi Alderman

(Winner of the [Bailey’s] Women’s Prize)

I read the first ~120 pages and skimmed the rest. Alderman imagines a parallel world in which young women realize they wield electrostatic power that can maim or kill. In an Arab Spring-type movement, they start to take back power from their oppressive societies. You’ll cheer as women caught up in sex trafficking fight back and take over. The movement is led by Allie, an abused child who starts by getting revenge on her foster father and then takes her message worldwide, becoming known as Mother Eve.

I read the first ~120 pages and skimmed the rest. Alderman imagines a parallel world in which young women realize they wield electrostatic power that can maim or kill. In an Arab Spring-type movement, they start to take back power from their oppressive societies. You’ll cheer as women caught up in sex trafficking fight back and take over. The movement is led by Allie, an abused child who starts by getting revenge on her foster father and then takes her message worldwide, becoming known as Mother Eve.

Alderman has cleverly set this up as an anthropological treatise-cum-historical novel authored by “Neil Adam Armon” (an anagram of her own name), complete with documents and drawings of artifacts. “The power to hurt is a kind of wealth,” and in this situation of gender reversal women gradually turn despotic. They are soldiers and dictators; they inflict genital mutilation and rape on men.

I enjoyed the passages mimicking the Bible, but felt a lack of connection with the characters and didn’t get a sense of years passing even though this is spread over about a decade. This is most like Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy – Alderman’s debt to Atwood is explicit, in the dedication as well as the acknowledgments – so if you really like those books, by all means read this one. My usual response to such speculative fiction, though, even if it describes a believable situation, is: what’s the point? As with “Erewhon,” the best story in Helen Simpson’s collection Cockfosters, the points about gender roles are fairly obvious.

I’d be interested to hear if you’ve read any of these books – or plan to read them – and believe they were worthy prize winners. If so, set me straight!

Three Perfect November Reads

It occurred to me that I’ve read three novels with “November” in the title. They’re extremely different from each other: one’s a melancholy 1930s American classic; one’s a quirky Icelandic road trip; and the last is a darker entry in a beloved Scandinavian children’s series. All are interesting books, though, and worth reading if you’re in the right mood.

Now in November by Josephine Johnson

(Reviewed here in full back in May.)

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November, which won the 1935 Pulitzer Prize. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. The arrival of Grant Koven, a neighbor in his thirties hired to help with hard labor, seems like the only thing that might break the agricultural cycle of futile hope and disappointment. Marget quickly falls in love with him, but it takes her a while to realize that her two sisters are smitten too. They all keep hoping their fortunes will change, but as drought settles in, things only get worse. This is an atmospheric and strangely haunting novel. The plot is simple enough, but the writing elevates it into something special. The plaintive tone, folksy metaphors, and philosophical earnestness all kept me eagerly traveling along with Marget to see where the tragic story might lead.

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November, which won the 1935 Pulitzer Prize. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. The arrival of Grant Koven, a neighbor in his thirties hired to help with hard labor, seems like the only thing that might break the agricultural cycle of futile hope and disappointment. Marget quickly falls in love with him, but it takes her a while to realize that her two sisters are smitten too. They all keep hoping their fortunes will change, but as drought settles in, things only get worse. This is an atmospheric and strangely haunting novel. The plot is simple enough, but the writing elevates it into something special. The plaintive tone, folksy metaphors, and philosophical earnestness all kept me eagerly traveling along with Marget to see where the tragic story might lead.

Butterflies in November by Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir

This is a whimsical, feminist road trip novel. The unnamed narrator is a translator based in Reykjavík. When her best friend slips on an icy sidewalk and breaks her arm, it falls to the narrator to care for the friend’s deaf-mute four-year-old son, Tumi. Leaving behind romantic troubles and boosted by not one but two lottery wins, she and the boy set off on a snowy voyage around Iceland’s Ring Road, with plenty of madcap adventures ahead. The plot is rather scattered and uneven, with uproarious mishaps followed by tedious passages. However, in this kooky fictional world where “nothing is as it should be any more,” where butterflies are still flying in November, the narrator’s tragicomic travels should still strike a chord. Recommended for fans of zany Scandinavian fiction such as The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out of the Window and Disappeared by Jonas Jonasson, or Doppler by Erlend Loe. (See my full review at For Books’ Sake.)

This is a whimsical, feminist road trip novel. The unnamed narrator is a translator based in Reykjavík. When her best friend slips on an icy sidewalk and breaks her arm, it falls to the narrator to care for the friend’s deaf-mute four-year-old son, Tumi. Leaving behind romantic troubles and boosted by not one but two lottery wins, she and the boy set off on a snowy voyage around Iceland’s Ring Road, with plenty of madcap adventures ahead. The plot is rather scattered and uneven, with uproarious mishaps followed by tedious passages. However, in this kooky fictional world where “nothing is as it should be any more,” where butterflies are still flying in November, the narrator’s tragicomic travels should still strike a chord. Recommended for fans of zany Scandinavian fiction such as The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out of the Window and Disappeared by Jonas Jonasson, or Doppler by Erlend Loe. (See my full review at For Books’ Sake.)

Moominvalley in November by Tove Jansson

Jansson said that after the Second World War she was depressed and wanted to write about something naïve and innocent. She wrote the first book of the Moomins series in 1945, about a family of hippo-like white trolls. But the Moomins do not appear in this book at all. It is November, the days are closing in, and no one knows where they have gone and when they might come back. A series of visitors journey to Moominvalley and find the house empty, cold and strange; these interlopers try to make their own merriment with a picnic and a party, but it all falls flat. The book felt unique to me for its Scandinavian qualities: the strange sprite-like creatures, woodland settings and short winter days, and the slight air of depression. As with the best children’s fiction, there is much here to entertain adults. Perhaps the most fun aspect of the book is Jansson’s original black and white line drawings of her peculiarly loveable creations.

Jansson said that after the Second World War she was depressed and wanted to write about something naïve and innocent. She wrote the first book of the Moomins series in 1945, about a family of hippo-like white trolls. But the Moomins do not appear in this book at all. It is November, the days are closing in, and no one knows where they have gone and when they might come back. A series of visitors journey to Moominvalley and find the house empty, cold and strange; these interlopers try to make their own merriment with a picnic and a party, but it all falls flat. The book felt unique to me for its Scandinavian qualities: the strange sprite-like creatures, woodland settings and short winter days, and the slight air of depression. As with the best children’s fiction, there is much here to entertain adults. Perhaps the most fun aspect of the book is Jansson’s original black and white line drawings of her peculiarly loveable creations.

Favorite passage: “The quiet transition from autumn to winter is not a bad time at all. It’s a time for protecting and securing things and for making sure you’ve got in as many supplies as you can. It’s nice to gather together everything you possess as close to you as possible, to store up your warmth and your thoughts and burrow yourself into a deep hole inside, a core of safety where you can defend what is important and precious and your very own. Then the cold and the storms and the darkness can do their worst. They can grope their way up the walls looking for a way in, but they won’t find one, everything is shut, and you sit inside, laughing in your warmth and your solitude, for you have had foresight.”

[On my TBR: November Storm by Robert Oldshue, a recent short story collection.]

Have you read these or any other “November” books?

Now in November by Josephine Johnson

I’d never heard of this 1935 Pulitzer Prize winner before I saw a large display of titles from publisher Head of Zeus’s new imprint, Apollo, at Foyles bookshop in London the night of the Diana Athill event. Apollo, which launched with eight titles in April, aims to bring lesser-known classics out of obscurity: by making “great forgotten works of fiction available to a new generation of readers,” it intends to “challenge the established canon and surprise readers.” I’ll be reviewing Howard Spring’s My Son, My Son for Shiny New Books soon, and I’m tempted by the Eudora Welty and Christina Stead titles. Rounding out the list are two novels set in Eastern Europe, a Sardinian novel in translation, and an underrated Western.

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. She recognizes how unsuited her father, Arnold, was to farming: “He hadn’t the resignation that a farmer has to have – that resignation which knows how little use to hope or hate.” The remaining members of this female-dominated household are mother Willa, older sister Kerrin and younger sister Merle. Half-feral Kerrin is a creature apart. She’s always doing something unpredictable, like demonstrating knife-throwing to disastrous effect or taking over as the local schoolteacher, a job she’s not at all right for.

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. She recognizes how unsuited her father, Arnold, was to farming: “He hadn’t the resignation that a farmer has to have – that resignation which knows how little use to hope or hate.” The remaining members of this female-dominated household are mother Willa, older sister Kerrin and younger sister Merle. Half-feral Kerrin is a creature apart. She’s always doing something unpredictable, like demonstrating knife-throwing to disastrous effect or taking over as the local schoolteacher, a job she’s not at all right for.

The arrival of Grant Koven, a neighbor in his thirties hired to help Arnold with hard labor, seems like the only thing that might break the agricultural cycle of futile hope and disappointment. Marget quickly falls in love with him, but it takes her a while to realize that her sisters are smitten too. They all keep hoping their fortunes will change:

‘This year will have to be different,’ I thought. ‘We’ve scrabbled and prayed too long for it to end as the others have.’ The debt was still like a bottomless swamp unfilled, where we had gone year after year, throwing in hours of heat and the wrenching on stony land, only to see them swallowed up and then to creep back and begin again.

Yet as drought settles in, things only get worse. The fear of losing everything becomes a collective obsession; a sense of insecurity pervades the community. The Ramseys, black tenant farmers with nine children, are evicted. Milk producers go on strike and have to give the stuff away before it sours. Nature is indifferent and neither is there a benevolent God at work: when the Haldmarnes go to church, they are refused communion as non-members.

Marget skips around in time to pinpoint the central moments of their struggle, her often fragmentary thoughts joined by ellipses – a style that seemed to me ahead of its time:

if anything could fortify me against whatever was to come […] it would have to be the small and eternal things – the whip-poor-wills’ long liquid howling near the cave… the shape of young mules against the ridge, moving lighter than bucks across the pasture… things like the chorus of cicadas, and the ponds stained red in evenings.

Michael Schmidt, the critic who selected the first eight Apollo books, likens Now in November to the work of two very different female writers: Marilynne Robinson and Emily Brontë. What I think he is emphasizing with those comparisons is the sense of isolation and the feeling that struggle is writ large on the landscape. The Haldmarne sisters certainly wander the nearby hills like the Brontë sisters did the Yorkshire moors.

The cover image, reproduced in full on the endpapers, is Jackson Pollock’s “Man with Hand Plow,” c. 1933.

As points of reference I would also add Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres and Joan Chase’s During the Reign of the Queen of Persia (resurrected by NYRB Classics in 2014), which also give timeless weight to the female experience of Midwest farming. Like the Smiley, Now in November stars a trio of sisters and makes conscious allusions to King Lear. Kerrin reads the play and thinks of their father as Lear, while Marget quotes it as a prophecy that the worst is yet to come: “I remembered the awful words in Lear: ‘The worst is not so long as we can say “This is the worst.”’ Already this year, I’d cried, This is enough! uncounted times, and the end had never come.”

Johnson lived to age 80 and published another 11 books, but nothing ever lived up to the success of her first. This is an atmospheric and strangely haunting novel. The plot is simple enough, but the writing elevates it into something special. The plaintive tone, the folksy metaphors, and the philosophical earnestness all kept me eagerly traveling along with Marget to see where this tragic story might lead. Apollo has done the literary world a great favor in bringing this lost classic to light.

With thanks to Blake Brooks at Head of Zeus for the free copy.

My rating:

What Makes a Review Popular?

I’ve only been reviewing on Goodreads for a couple years, but in that time I’ve noticed some contradictory trends. The most-liked reviews can be thousands of words long or two sentences; disjointed ramblings or concise analysis; gif after gif (screen captures of moving or still images from TV or film) or pure text; strewn with typos or perfectly honed; personal or detached; gimmicky or straightforward; gushing praise or forthright dismissal. In other words, I’m somewhat puzzled as to what makes a review popular.

To some extent it’s down to the popularity of a reviewer: the more friends and followers they have, the more likely people are to ‘like’ their review (if you’re not familiar with Goodreads, it has a ‘like’ button just like on Facebook, and reviews of a certain book then arrange themselves in order with the ones with the highest likes on the top). But this isn’t a sure thing. Although top reviewers probably account for a good percentage of the most popular reviews, there are always those sneaky book reviews that come out of nowhere and go viral.

Here are my thoughts on what is likely to make a review popular, thinking not just of Goodreads but of other sites I’ve worked with:

The book has buzz already, and/or has won a major prize.

By far, my most popular review ever is of Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries [458 likes]. It won the Man Booker Prize in 2013.

My second most popular review ever is of Gabrielle Zevin’s The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry [264 likes]. It was a New York Times bestseller and especially successful with the bookish types on Goodreads.

My second most popular review ever is of Gabrielle Zevin’s The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry [264 likes]. It was a New York Times bestseller and especially successful with the bookish types on Goodreads.

To my knowledge, our most popular article ever published on Bookkaholic was a book debate we did about Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2013. I rated it 3 stars, while my opponent, an Australian blogger, gave it 5.

There’s thousands of 5-star ratings for Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, the 2015 Pulitzer winner, so while mine is not one of the top reviews by any means, it’s still my fifth most popular one at 62 likes.

You get in there early.

Mine was one of the first reviews of The Luminaries to hit Goodreads, thanks to an advanced reader’s copy sent to me by We Love This Book. I also managed to review A.J. Fikry a few weeks before the publication date thanks to an Edelweiss download. With an early review, you can sometimes set the trend.

Mine was one of the first reviews of The Luminaries to hit Goodreads, thanks to an advanced reader’s copy sent to me by We Love This Book. I also managed to review A.J. Fikry a few weeks before the publication date thanks to an Edelweiss download. With an early review, you can sometimes set the trend.

Helen Macdonald’s superb memoir, H is for Hawk, was released in the UK about a year before it finally arrived in the States, so that allowed my review time to gain some momentum (though not as much as a review that contained lots of photographs, something I still haven’t figured out how to do in html). It’s my sixth most popular review at 48 likes.

You epitomize the positive (or dissenting) response.

My third most popular review is of Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being [138 likes], one of my favorite books from 2013 or any year. That was an unreserved 5-star rating. My 5-star review of Jo Baker’s Longbourn, my fourth most popular at 64 likes, went up the week of publication and started off strong before being overtaken by some other positive reviews.

My third most popular review is of Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being [138 likes], one of my favorite books from 2013 or any year. That was an unreserved 5-star rating. My 5-star review of Jo Baker’s Longbourn, my fourth most popular at 64 likes, went up the week of publication and started off strong before being overtaken by some other positive reviews.

By contrast, my reviews of The Luminaries and A.J. Fikry are lukewarm and critical, respectively. For the latter, I seem to represent the negative response: people who were disappointed by how clichéd and sappy a promising bibliophile’s novel turned out to be.

[Note: The above numbers were correct as of October 12, 2015; I will now stop updating them as it was taking up too much of my time and memory! My Goodreads teaser for A Little Life has now overtaken H is for Hawk as my sixth most popular review.]

Do you have any theories as to what makes a review popular? If you’re a blogger and/or reviewer, what have been some of your most popular pieces?

All comments welcome!

In Praise of Literary Prizes

I like a spot of competition. Whether watching Olympic figure skating, playing board games like Scrabble and Boggle, entering a low-key Oscars pool, or rooting for my favorites in American Idol seasons and Miss America pageants, I’ve always loved trying to pick the best. This means that literary prizes are hugely exciting for me, and I follow the races closely.

I’m particularly devoted to the Man Booker Prize. I was delighted to see Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life on the recent longlist (catch up on it here), a truly interesting set of books, diverse in terms of their genres and authors’ nationalities and nicely balanced between male and female writers (6:7). I’ve read four of the longlisted titles so far:

The Fishermen, Chigozie Obioma (full review in May 2015 issue of Third Way): From a young Nigerian debut novelist comes a haunting tale of sibling rivalry and revenge. With sectarian riots afoot, the four oldest Agwu boys decide to make money by skipping school and fishing in the Omi-Ala River. Things get more complicated when Abulu, the local madman, issues a prophecy that seems bound to divide the brothers. The first quarter of the novel, especially, is drenched in foreshadowing (not always subtle, nor do the plot turns often rise above the predictable). Rich with prophecy and allusions, this owes much to biblical narratives and tragedies from Shakespeare to Chinua Achebe.

The Fishermen, Chigozie Obioma (full review in May 2015 issue of Third Way): From a young Nigerian debut novelist comes a haunting tale of sibling rivalry and revenge. With sectarian riots afoot, the four oldest Agwu boys decide to make money by skipping school and fishing in the Omi-Ala River. Things get more complicated when Abulu, the local madman, issues a prophecy that seems bound to divide the brothers. The first quarter of the novel, especially, is drenched in foreshadowing (not always subtle, nor do the plot turns often rise above the predictable). Rich with prophecy and allusions, this owes much to biblical narratives and tragedies from Shakespeare to Chinua Achebe.- Lila, Marilynne Robinson – reviewed at For Books’ Sake

- A Spool of Blue Thread, Anne Tyler – also reviewed at For Books’ Sake

- A Little Life, Hanya Yanagihara – reviewed at Shiny New Books

Next up: I’m reviewing The Green Road by Anne Enright for the November 2015 issue of Third Way. The Booker Prize shortlist will be announced on September 15th and the winner on October 13th.

Next up: I’m reviewing The Green Road by Anne Enright for the November 2015 issue of Third Way. The Booker Prize shortlist will be announced on September 15th and the winner on October 13th.

Beyond the Booker, here are some of the other prizes I follow throughout the year, listed in vague chronological order:

The Not the Booker Prize run by the Guardian. On this year’s shortlist is Shame by Melanie Finn, a book I loved when I reviewed it for Third Way’s April 2015 issue. It’s a powerful story of regret and the search for redemption. Though it has elements of a straightforward psychological thriller, the daring structure and moral complexities are more akin to Graham Greene. In alternating chapters, Pilgrim Jones contrasts flashbacks to her car accident and the subsequent investigation back in Switzerland with her present-tense African odyssey. This is Conrad’s Africa, a continent characterized by darkness and suffering. The question of culpability remains murky, yet the possibility of salvation shines through. [Voting will take place in October.]

The Not the Booker Prize run by the Guardian. On this year’s shortlist is Shame by Melanie Finn, a book I loved when I reviewed it for Third Way’s April 2015 issue. It’s a powerful story of regret and the search for redemption. Though it has elements of a straightforward psychological thriller, the daring structure and moral complexities are more akin to Graham Greene. In alternating chapters, Pilgrim Jones contrasts flashbacks to her car accident and the subsequent investigation back in Switzerland with her present-tense African odyssey. This is Conrad’s Africa, a continent characterized by darkness and suffering. The question of culpability remains murky, yet the possibility of salvation shines through. [Voting will take place in October.]

- The Guardian First Book Award (open to both fiction and nonfiction): the shortlist will be announced this Friday, August 14th. One entry, Spill Simmer Falter Wither by Sara Baume, has already been chosen by readers, and the other nine are selected from publishers’ submissions. [Winner announced in late November.]

The Dylan Thomas Prize for young writers (under 39) went to Joshua Ferris for To Rise Again at a Decent Hour last year. [Longlist in September, shortlist in October and winner announced in November.]

The Dylan Thomas Prize for young writers (under 39) went to Joshua Ferris for To Rise Again at a Decent Hour last year. [Longlist in September, shortlist in October and winner announced in November.]

- The Costa Book Awards give separate prizes for fiction, debut fiction, biography, poetry, and children’s books, and also choose one overall winner. [Category shortlists in late November, category winners in early January and overall winner on January 26, 2016.]

- The Folio Prize, only two years old, considers any work of fiction published in English; before the Booker expanded to include American entries last year, it was the most Catholic of the fiction prizes. Now it risks being considered redundant; especially since it lost its Folio Society sponsorship, it’s unclear whether it will continue. [Shortlist in February and winner announced in March.]

The Wellcome Book Prize is for medical-themed literature, fiction or nonfiction. Last year’s winner, The Iceberg by Marion Coutts, meant a lot to me for personal reasons but was also one of the most unusual and impressive memoirs I’ve ever read. I reviewed it for The Bookbag here. [Shortlist in March and winner announced in April.]

The Wellcome Book Prize is for medical-themed literature, fiction or nonfiction. Last year’s winner, The Iceberg by Marion Coutts, meant a lot to me for personal reasons but was also one of the most unusual and impressive memoirs I’ve ever read. I reviewed it for The Bookbag here. [Shortlist in March and winner announced in April.]

- The Pulitzer Prize is America’s premier literary award. I confess I often feel a little out of touch with the winners and don’t necessarily make a conscious effort to seek out the nominated books. I’d like to be more familiar with Pulitzer winners. Next year marks the prize’s centennial, so there’s no better time! [Winners announced in April.]

- The Independent Foreign Fiction Prize is for any book that has been translated into English and published in the UK in the previous year. I’ve found some great offbeat reads by browsing through previous longlists. As of next year, the prize is merging with the Man Booker International award, which previously recognized the life work of a foreign author every other year. [Longlist in March, shortlist in April and winner announced in May.]

The Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize, the UK’s prize for comic literature, has run since 2000. Among the past winners are Paul Torday, Howard Jacobson, Terry Pratchett, Geoff Dyer, Gary Shteyngart, and (surprise!) Ian McEwan. I’ve read five of the winners, including Lost for Words by Edward St. Aubyn. [Shortlist in March and winner announced in May.]

The Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize, the UK’s prize for comic literature, has run since 2000. Among the past winners are Paul Torday, Howard Jacobson, Terry Pratchett, Geoff Dyer, Gary Shteyngart, and (surprise!) Ian McEwan. I’ve read five of the winners, including Lost for Words by Edward St. Aubyn. [Shortlist in March and winner announced in May.]

- The Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction (formerly known as the Orange Prize). Ali Smith won the 2015 award for How to Be Both. [Longlist in March; shortlist and winner announced in June.]

Do you follow literary prize races? Do you make a point of reading the winner and/or the shortlisted books? All comments welcome!

I Like Big Books and I Cannot Lie

You can never get a cup of tea large enough or a book long enough to suit me.

~ C. S. Lewis

Here’s to doorstoppers! Books of 500 pages or more [the page count is in brackets for each of the major books listed below] can keep you occupied for entire weeks of a summer – or for just a few days if they’re gripping enough. There’s something delicious about getting wrapped up in an epic story and having no idea where the plot will take you. Doorstoppers are the perfect vacation companions, for instance. I have particularly fond memories of getting lost in Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke [782] on a week’s boating holiday in Norfolk with my in-laws, and of devouring The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber [835] on a long, queasy ferry ride to France.

Here’s to doorstoppers! Books of 500 pages or more [the page count is in brackets for each of the major books listed below] can keep you occupied for entire weeks of a summer – or for just a few days if they’re gripping enough. There’s something delicious about getting wrapped up in an epic story and having no idea where the plot will take you. Doorstoppers are the perfect vacation companions, for instance. I have particularly fond memories of getting lost in Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke [782] on a week’s boating holiday in Norfolk with my in-laws, and of devouring The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber [835] on a long, queasy ferry ride to France.

I have an MA in Victorian Literature, so I was used to picking up novels that ranged between 600 and 900 pages. Of course, one could argue that the Victorians were wordier than necessary due to weekly deadlines, the space requirements of serialized stories, and the popularity of subsequent “triple-decker” three-volume publication. Still, I think Charles Dickens’s works, certainly, stand the test of time. His David Copperfield [~900] is still my favorite book. I adore his sprawling stories crammed full of major and minor characters. Especially in a book like David Copperfield that spans decades of a character’s life, the sheer length allows you time to get to know the protagonist intimately and feel all his or her struggles and triumphs as if they were your own.

I felt the same about A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara [720], which I recently reviewed for Shiny New Books. Jude St. Francis is a somewhat Dickensian character anyway, for his orphan origins at least, and even though the novel is told in the third person, it is as close a character study as you will find in contemporary literature. I distinctly remember two moments in my reading, one around page 300 and one at 500, when I looked up and thought, “where in the world will this go?!” Even as I approached the end, I couldn’t imagine how Yanagihara would leave things. That, I think, is one mark of a truly masterful storyteller.

Speaking of Dickensian novels, in recent years I’ve read two Victorian pastiches that have an authentically Victorian page count, too: The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton [848] and Death and Mr. Pickwick by Stephen Jarvis [816]. The Luminaries, which won the 2013 Booker Prize, has an intricate structure (based on astrological charts) that involves looping back through the same events – making it at least 200 pages too long.

It was somewhat disappointing to read Jarvis’s debut novel in electronic format; without the physical signs of progress – a bookmark advancing through a huge text block – it’s more difficult to feel a sense of achievement. Once again one might argue that the book’s digressive nature makes it longer than necessary. But with such an accomplished debut that addresses pretty much everything ever written or thought about The Pickwick Papers, who could quibble?

John Irving’s novels are Dickensian in their scope as well as their delight in characters’ eccentricities, but fully modern in terms of themes – and sexual explicitness. Along with Dickens, he’s a mutual favorite author for my husband and me, and his A Prayer for Owen Meany [637] numbers among our collective favorite novels. Most representative of his style are The World According to Garp and The Cider House Rules.

Here are a handful of other long novels I’ve read and reviewed within the last few years (the rating is below each description):

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr [531] – The 2015 Pulitzer Prize winner; set in France and Germany during World War II.

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr [531] – The 2015 Pulitzer Prize winner; set in France and Germany during World War II.

In the Light of What We Know by Zia Haider Rahman [555] – Digressive intellectualizing about race, class and war as they pertain to British immigrants.

The Son by Philipp Meyer [561] – An old-fashioned Western with hints of Cormac McCarthy.

The Son by Philipp Meyer [561] – An old-fashioned Western with hints of Cormac McCarthy.

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach [512] – Baseball is a window onto modern life in this debut novel about homosocial relationships at a small liberal arts college.

“A Discovery of Witches” fantasy trilogy by Deborah Harkness: A Discovery of Witches [579], Shadow of Night [584], and The Book of Life [561] – Thinking girl’s vampire novels, with medieval history and Oxford libraries thrown in.

“A Discovery of Witches” fantasy trilogy by Deborah Harkness: A Discovery of Witches [579], Shadow of Night [584], and The Book of Life [561] – Thinking girl’s vampire novels, with medieval history and Oxford libraries thrown in.

And here’s the next set of doorstoppers on the docket:

Of Human Bondage by W. Somerset Maugham [766] – A Dickensian bildungsroman about a boy with a clubfoot who pursues art, medicine and love.

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt [864] – I have little idea of what this is actually about. A boy named Theo, art, loss, drugs and 9/11? Or just call it life in general. I’ve read Tartt’s other two books and was enough of a fan to snatch up a secondhand paperback for £1.

A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James [686] (as with A Little Life, the adjective in the title surely must be tongue-in-cheek!) – The starting point is an assassination attempt on Bob Marley in the late 1970s, but this is a decades-sweeping look at Jamaican history. I won a copy in a Goodreads giveaway.

A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth [1,474!] – A sprawling Indian family saga. Apparently he’s at work on a sequel entitled A Suitable Girl.

This Thing of Darkness by Harry Thompson [744] – A novel about Charles Darwin and his relationship with Robert FitzRoy, captain of the Beagle.

The Last Chronicle of Barset by Anthony Trollope [891] – As the title suggests, this is the final novel in Trollope’s six-book “Chronicles of Barsetshire” series. Alas, reading this one requires reading the five previous books, so this is more like a 5,000-page commitment…

Now, a confession: sometimes I avoid long books because they just seem like too much work. It’s sad but true that a Dickens novel takes me infinitely longer to read than a modern novel of similar length. The prose is simply more demanding, there’s no question about it. So if I’m faced with a choice between one 800-page novel that I know could take me months of off-and-on reading and three or four 200–300-page contemporary novels, I’ll opt for the latter every time. Part of this also has to do with meeting my reading goals for the year: when you’re aiming for 250 titles, it makes more sense to read a bunch of short books than a few long ones. I need to get better about balancing quality and quantity.

How do you feel about long books? Do you seek them out or shy away? Comments welcome!

This collects 55 short pieces under three headings: literature, visual arts, and travel. Alongside straightforward book reviews are essays in which Cole engages with his literary heroes. A 400-page book of disparate essays is a hard ask, and even photography aficionados may struggle through the long middle section. All the same, patience is rewarded by Part III, “Being There,” in which he deftly blends memoir and travelogue. Again and again he reflects on displacement and ambiguity. Born in Michigan but raised in Nigeria, Cole returned to the States for college. Though erudite and wide-ranging, these essays are not quite as successful as, say, Julian Barnes’s or Geoff Dyer’s in making any and every topic interesting to laymen. Still, Cole proves himself a modern Renaissance man, interweaving experience and opinion in rigorous yet conversational pieces that illuminate the arts. (See my full review on the

This collects 55 short pieces under three headings: literature, visual arts, and travel. Alongside straightforward book reviews are essays in which Cole engages with his literary heroes. A 400-page book of disparate essays is a hard ask, and even photography aficionados may struggle through the long middle section. All the same, patience is rewarded by Part III, “Being There,” in which he deftly blends memoir and travelogue. Again and again he reflects on displacement and ambiguity. Born in Michigan but raised in Nigeria, Cole returned to the States for college. Though erudite and wide-ranging, these essays are not quite as successful as, say, Julian Barnes’s or Geoff Dyer’s in making any and every topic interesting to laymen. Still, Cole proves himself a modern Renaissance man, interweaving experience and opinion in rigorous yet conversational pieces that illuminate the arts. (See my full review on the

A perfect novel about a few months of Thomas Hardy’s later life. On the surface it’s the story of a rather odd love triangle: the octogenarian Hardy was infatuated with Gertrude Bugler, a local Dorset actress who had agreed to play his Tess on the London stage; his neurotic second wife, Florence, got wind of his feelings and jealously decided to sabotage Gertie. Underneath, I found this to be a deeply moving book about fear – of death, but also of not having lived the way you wanted and meant to. The perspective moves between Florence and Gertie in the first person and an omniscient third-person narrator. Chapters 1, 6 and 8, in particular, are a pitch-perfect pastiche of Hardy’s style. A bleak country winter is the perfect setting for a story of personal decay and a marriage grown cold. This brought back vivid memories of my visit to Hardy’s house in 2004 and coincided with my own vision of who Hardy was.

A perfect novel about a few months of Thomas Hardy’s later life. On the surface it’s the story of a rather odd love triangle: the octogenarian Hardy was infatuated with Gertrude Bugler, a local Dorset actress who had agreed to play his Tess on the London stage; his neurotic second wife, Florence, got wind of his feelings and jealously decided to sabotage Gertie. Underneath, I found this to be a deeply moving book about fear – of death, but also of not having lived the way you wanted and meant to. The perspective moves between Florence and Gertie in the first person and an omniscient third-person narrator. Chapters 1, 6 and 8, in particular, are a pitch-perfect pastiche of Hardy’s style. A bleak country winter is the perfect setting for a story of personal decay and a marriage grown cold. This brought back vivid memories of my visit to Hardy’s house in 2004 and coincided with my own vision of who Hardy was.

The only graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize, this brings the Holocaust home in a fresh way. Like Animal Farm, it uses the conceit of various animal associations: Jews are mice, Poles are pigs, Nazis are cats, and Americans are dogs. Spiegelman draws what, from a distance of decades, his father Vladek remembers about his almost unbelievable series of escapes, including time in Auschwitz. Spiegelman gives the book an extra dimension by including his 1970s/80s recording sessions with his father as a framing story for most chapters. The narration is thus in Vladek’s own broken English, and we see how exasperating Spiegelman finds him – for pinching pennies and being racist against blacks, for instance – even as he’s in awe of his story. You can see how this paved the way for comic artists like Roz Chast and Alison Bechdel. I recommend it to absolutely anyone, graphic novel fan or no.

The only graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize, this brings the Holocaust home in a fresh way. Like Animal Farm, it uses the conceit of various animal associations: Jews are mice, Poles are pigs, Nazis are cats, and Americans are dogs. Spiegelman draws what, from a distance of decades, his father Vladek remembers about his almost unbelievable series of escapes, including time in Auschwitz. Spiegelman gives the book an extra dimension by including his 1970s/80s recording sessions with his father as a framing story for most chapters. The narration is thus in Vladek’s own broken English, and we see how exasperating Spiegelman finds him – for pinching pennies and being racist against blacks, for instance – even as he’s in awe of his story. You can see how this paved the way for comic artists like Roz Chast and Alison Bechdel. I recommend it to absolutely anyone, graphic novel fan or no.  Bawdy, witty, vivid historical fiction; simply brilliant. You’ll never doubt for a second that you are in 1746 New York – an English colony with a heavy Dutch influence, and slavery still the standard. The novel opens suddenly as twenty-four-year-old Richard Smith arrives from London with a promissory note for £1000. He won’t explain how he came by the money or what he intends to do with it, but the order seems legitimate. This puts the merchant Mr. Lovell in rather a bind, because that kind of cash simply can’t be come by. Before he can finally get his money, Smith will fall in and out of love, fight a duel, and be arrested twice – all within the space of two months. In a book full of fantastic scenes, Smith and Septimus’ narrow escape via the rooftops on Pope Day stands out. The finest thing about the novel, though, is the authentic eighteenth-century diction. Spufford writes very good creative nonfiction, with five books to date, but with his debut novel he’s hit a home run.

Bawdy, witty, vivid historical fiction; simply brilliant. You’ll never doubt for a second that you are in 1746 New York – an English colony with a heavy Dutch influence, and slavery still the standard. The novel opens suddenly as twenty-four-year-old Richard Smith arrives from London with a promissory note for £1000. He won’t explain how he came by the money or what he intends to do with it, but the order seems legitimate. This puts the merchant Mr. Lovell in rather a bind, because that kind of cash simply can’t be come by. Before he can finally get his money, Smith will fall in and out of love, fight a duel, and be arrested twice – all within the space of two months. In a book full of fantastic scenes, Smith and Septimus’ narrow escape via the rooftops on Pope Day stands out. The finest thing about the novel, though, is the authentic eighteenth-century diction. Spufford writes very good creative nonfiction, with five books to date, but with his debut novel he’s hit a home run.

From a prolific author of both fiction and nonfiction, a meticulously researched novel about George Forster, one of the naturalists on Captain Cook’s second voyage. Rather than giving a simple chronological account of the journey and its aftermath, Wilson employs a sophisticated structure that alternates vignettes from the voyage with scenes from about 10 years later, when George is unhappily married to Therese and struggling to find suitable work. This is the second novel I’ve read by Wilson, after The Potter’s Hand. I find his fiction to be thoroughly convincing as well as engaging. This reminded me most of

From a prolific author of both fiction and nonfiction, a meticulously researched novel about George Forster, one of the naturalists on Captain Cook’s second voyage. Rather than giving a simple chronological account of the journey and its aftermath, Wilson employs a sophisticated structure that alternates vignettes from the voyage with scenes from about 10 years later, when George is unhappily married to Therese and struggling to find suitable work. This is the second novel I’ve read by Wilson, after The Potter’s Hand. I find his fiction to be thoroughly convincing as well as engaging. This reminded me most of