How People Found My Blog Recently

I’m always interested to find out how people who aren’t regular followers catch wind of my blog. The web searches documented in my WordPress statistics are often bizarre, but do point to what have been some of my most enduringly popular posts: reviews of The First Bad Man, The Girl Who Slept with God, and The Essex Serpent; and write-ups of events with Diana Athill and Michel Faber. I also get a fair number of searches for Ann Kidd Taylor, whose two books I’ve featured at different points.

Here are some of the more interesting results from the last six months or so. My favorite search of all may well be “underwhelmed by ferrante”! (Spelling and punctuation are unedited throughout.)

October 19: the undiscovered islands malachy tallack, the first bad man, ann kidd taylor wedding

October 21: prose/poetry about autumn

November 2: ann kidd taylor, irmina barbara yelin, the first bad man summary, diana athill on molly keane

November 6: michel faber poems, essex serpent as byatt, book summary of the girl who slept with gid byval brelinski

November 17: book cycle, james lasdun, novel the girl who slept with god

November 25: john bradshaw the lion in the living room, bibliotherapy open courses the school of life, barbara yelin irmina, 2016 best prose poem extracts

December 5: seal morning, paul evans field notes from the edge, at the existentialist café: freedom, being, and apricot cocktails with jean-paul sartre, simone de beauvoir, albert camus, marti, read how many books at once

December 23: midwinter novel melrose, underwhelmed by ferrante

January 6: charlotte bronte handwriting, hundred year old man and john irving

January 12: memorable prose on looking forward, felicity Trotman

January 24: patient memoirs, poirot graphic novel, first bad man review, he came beck why? love poems

January 26: reading discussion essex serpent, elena ferrante my brilliant friend dislike

February 3: what are chimamanda’s novels transkated to films, ann kidd taylor, shannon leone fowler, i read war and peace and liked it

February 15: “how to make a french family” “review”, book that literally changed my life, the essex serpent summary

March 13: my darling detective howard norman, the essex serpent book club questions, the first bad man summary

March 22: the doll’s alphabet, joslin linder genetic disorders

March 31: detor, louisa young michel faber

May 7: the essex serpent plot, rebecca foster writer, book about cats, gauguin the other world dori fabrizio

4 Reasons to Love Kayla Rae Whitaker’s The Animators

I have way too much to say about this terrific debut novel, and there’s every danger of me slipping into plot summary because, though it seems lighthearted on the surface, there’s a lot of meat to this story of the long friendship between two female animators. So I’m going to adapt a format that has worked well for other bloggers (e.g. Carolyn at Rosemary and Reading Glasses) and pull out four reasons why you must be sure not to miss this book.

I have way too much to say about this terrific debut novel, and there’s every danger of me slipping into plot summary because, though it seems lighthearted on the surface, there’s a lot of meat to this story of the long friendship between two female animators. So I’m going to adapt a format that has worked well for other bloggers (e.g. Carolyn at Rosemary and Reading Glasses) and pull out four reasons why you must be sure not to miss this book.

- Bosom Friends. Have you ever had, or longed for, what Anne Shirley calls a “bosom friend”? If so, you’ll love watching the friendship develop between narrator Sharon Kisses and her business partner, Mel Vaught. In many ways they are opposites. Lanky, blonde Mel is a loud, charismatic lesbian who uses drugs and alcohol to fuel a manic pace of life. She’s the life of every party. Sharon, on the other hand, is a curvy brunette and neurotic introvert who’s always falling in love with men but never achieving real relationships. They meet in Professor McIntosh’s Introduction to Sketch class at a small college and a decade later are still working together. They win acclaim for their first full-length animated feature, Nashville Combat, based on Mel’s dysfunctional upbringing in the Central Florida swamps. But they see each other through some really low lows, too, like the death of Mel’s mother and Sharon’s punishing recovery from a stroke at the age of 32.

She was the first person to see me as I had always wanted to be seen. It was enough to indebt me to her forever.

- The Value of Work. Kayla Rae Whitaker was inspired by her childhood obsession with dark, quirky cartoons like Beavis and Butthead and Ren and Stimpy. Books about artists sometimes present the work as magically fully-formed, rather than showing the arduous process behind it. Here, though, you track Mel and Sharon’s next film from a set of rough sketches in a secret notebook to a polished comic, following it through storyboarding, filling-in and final edits. It’s a year of all-nighters, poor diet and substance abuse. But work – especially the autobiographical projects these characters create – is also saving. Even when it seems the well has run dry, creativity always resurges. I also appreciated how the novel contrasts the women’s public and private personas and imagines their professional legacy.

The work will always be with you, will come back to you if it leaves, and you will return to it to find that you have, in fact, gotten better, gotten sharper. It happens to you while you are asleep inside.

- Road Trips and Rednecks. I love a good road trip narrative, and this novel has two. First there’s the drive down to Florida for Mel to identify her mother, and then there’s Sharon’s sheepish return to her hometown of Faulkner, Kentucky. Here’s where the book really takes off. The sharp, sassy dialogue sparkles throughout, but the scenes with Sharon’s mom and sister are particularly hilarious. What’s more, the contrast between the American heartland and the flashy New York City life Mel and Sharon have built works brilliantly. Although in the Kentucky section Whitaker portrays some obese Americans you’d be tempted to call white trash, she never resorts to cruel hillbilly stereotypes. The author herself is from rural eastern Kentucky and paints the place in a tender light. She even makes Louisville – where the friends go to meet up with Sharon’s old neighbor and first crush, Teddy Caudill – sound like quite an appealing tourist destination!

I used it to hate it here. How could I have possibly hated this? This is me. I sprang from this place.

I love the attention to detail evident in the book design, especially the black-and-white TV fuzz of the covers under the dust jacket, and the pop of neon green on the inside of the endpapers.

- Open Your Trunk. This is a mantra arising from Mel and Sharon’s second movie, Irrefutable Love, which is autobiographical for Sharon this time – revolving around a traumatic incident from her shared past with Teddy, her string of crushes, and her stroke recovery. One powerful message of the novel is that you can’t move on in life unless you confront the crap that’s happened to you. As humorous as it is, it’s also a weighty book in this respect. It has three pivot points, moments so grim and surprising that I could hardly believe Whitaker dared to put them in. (The first is Sharon’s stroke; the others I won’t spoil.) This means the ending is not the super-happy one I might have wanted, but it’s realistic.

Anything that makes you in that way, anything that makes you hurt and hungry in that way, is worth investigating. … When you take the things that happen to you, the things that make you who are, and you use them, you own them.

I thought the timeline could be a little tighter and the novel was unnecessarily crass in places. For me, the road trips were the best bits and the rest never quite matched up. But this is still bound to be one of my top novels of the year. I think every reader will see him/herself in Sharon, and we all know a Mel; for some it might be the other way around. Like A Little Life and even The Essex Serpent, this asks how friendship and work can carry us through. Meanwhile, the cartooning world and the Kentucky–New York City dichotomy together feel like a brand new setting for a literary tragicomedy.

An early favorite for 2017. Don’t miss it.

The Animators was published by Random House and Scribe UK on January 31st. My thanks to Sophie Leeds of Scribe for sending a free copy for review.

My rating:

2016 Runners-Up and Other Superlatives

Let’s hear it for the ladies! In 2016 women writers accounted for 9 out of my 15 top fiction picks, 12 out of my 15 nonfiction selections, and 8 of the 10 runners-up below. That’s 73%. The choices below are in alphabetical order by author, with any full reviews linked in. Many of these have already appeared on the blog in some form over the course of the year.

Ten Runners-Up:

FICTION

Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood: Atwood looks more like a good witch every year, and here she works her magic on The Tempest to produce the most satisfying volume of the Hogarth Shakespeare series yet. There’s a really clever play-within-the-play-within-the-play thing going on, and themes of imprisonment and performance resonate in multiple ways.

Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood: Atwood looks more like a good witch every year, and here she works her magic on The Tempest to produce the most satisfying volume of the Hogarth Shakespeare series yet. There’s a really clever play-within-the-play-within-the-play thing going on, and themes of imprisonment and performance resonate in multiple ways.

The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church: In Church’s debut, an amateur ornithologist learns about love and sacrifice through marriage to a Los Alamos physicist and a relationship with a Vietnam veteran. I instantly warmed to Meri as a narrator and loved following her unpredictable life story.

The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church: In Church’s debut, an amateur ornithologist learns about love and sacrifice through marriage to a Los Alamos physicist and a relationship with a Vietnam veteran. I instantly warmed to Meri as a narrator and loved following her unpredictable life story.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. This is a rich and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions; it’s a great first novel and I will follow Greenidge’s career with interest.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. This is a rich and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions; it’s a great first novel and I will follow Greenidge’s career with interest.

To the Bright Edge of the World by Eowyn Ivey: Ivey’s intricate second novel weaves together diaries, letters, photographs, and various other documents and artifacts to tell the gently supernatural story of an exploratory mission along Alaska’s Wolverine River in 1885 and its effects through to the present day. I can highly recommend this rollicking adventure tale to fans of historical fiction and magic realism.

by Eowyn Ivey: Ivey’s intricate second novel weaves together diaries, letters, photographs, and various other documents and artifacts to tell the gently supernatural story of an exploratory mission along Alaska’s Wolverine River in 1885 and its effects through to the present day. I can highly recommend this rollicking adventure tale to fans of historical fiction and magic realism.

This Must Be the Place by Maggie O’Farrell: Spreading outward from Ireland and reaching into every character’s past and future, this has all O’Farrell’s trademark insight into family and romantic relationships, as well as her gorgeous prose and precise imagery. I have always felt that O’Farrell expertly straddles the (perhaps imaginary) line between literary and popular fiction; her books are addictively readable but also hold up to critical scrutiny.

by Maggie O’Farrell: Spreading outward from Ireland and reaching into every character’s past and future, this has all O’Farrell’s trademark insight into family and romantic relationships, as well as her gorgeous prose and precise imagery. I have always felt that O’Farrell expertly straddles the (perhaps imaginary) line between literary and popular fiction; her books are addictively readable but also hold up to critical scrutiny.

Commonwealth by Ann Patchett: This deep study of blended family dynamics starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny; we see the aftermath of that party in the lives of six step-siblings in the decades to come. This is a sophisticated and atmospheric novel I would not hesitate to recommend to literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular.

by Ann Patchett: This deep study of blended family dynamics starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny; we see the aftermath of that party in the lives of six step-siblings in the decades to come. This is a sophisticated and atmospheric novel I would not hesitate to recommend to literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular.

The Last Painting of Sara de Vos by Dominic Smith: Jessie Burton, Tracy Chevalier and all others who try to write historical fiction about the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, eat your hearts out. Such a beautiful epoch-spanning novel about art and regret.

The Last Painting of Sara de Vos by Dominic Smith: Jessie Burton, Tracy Chevalier and all others who try to write historical fiction about the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, eat your hearts out. Such a beautiful epoch-spanning novel about art and regret.

Shelter by Jung Yun: A Korean-American family faces up to violence past and present in a strong debut that offers the hope of redemption. I would recommend this to fans of David Vann and Richard Ford.

NONFICTION

I Will Find You by Joanna Connors: By using present-tense narration, Connors makes the events of 1984 feel as if they happened yesterday: a blow-by-blow of the sex acts forced on her at knife-point over the nearly one-hour duration of her rape; the police reports and trials; and the effects it all had on her marriage and family. This is an excellent work of reconstruction and investigative reporting.

by Joanna Connors: By using present-tense narration, Connors makes the events of 1984 feel as if they happened yesterday: a blow-by-blow of the sex acts forced on her at knife-point over the nearly one-hour duration of her rape; the police reports and trials; and the effects it all had on her marriage and family. This is an excellent work of reconstruction and investigative reporting.

Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge: Younge built this book by choosing a 24-hour period (November 22 to 23, 2013) and delving into all 10 gun deaths of young Americans on record for that time: seven black, two Latino, and one white; aged nine to 18; about half at least vaguely gang-related, while in two – perhaps the most crushing cases – there was an accident while playing around with a gun. I dare anyone to read this and then try to defend gun ‘rights’ in the face of such senseless, everyday loss.

Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge: Younge built this book by choosing a 24-hour period (November 22 to 23, 2013) and delving into all 10 gun deaths of young Americans on record for that time: seven black, two Latino, and one white; aged nine to 18; about half at least vaguely gang-related, while in two – perhaps the most crushing cases – there was an accident while playing around with a gun. I dare anyone to read this and then try to defend gun ‘rights’ in the face of such senseless, everyday loss.

Various Superlatives:

Best Discoveries of the Year: Apollo Classics reprints (I reviewed three of them this year); Diana Abu-Jaber, Linda Grant and Kristopher Jansma.

Most Pleasant Year-Long Reading Experience: The seasonal anthologies issued by the UK Wildlife Trusts and edited by Melissa Harrison (I reviewed three of them this year).

Most Improved: I heartily disliked Sarah Perry’s debut novel, After Me Comes the Flood. But her second, The Essex Serpent, is exquisite.

Debut Novelists Whose Next Work I’m Most Looking Forward to: Stephanie Danler, Kaitlyn Greenidge, Francis Spufford, Andria Williams and Sunil Yapa.

The Year’s Biggest Disappointments: Here I Am by Jonathan Safran Foer, Today Will Be Different by Maria Semple, and Swing Time by Zadie Smith. Here’s hoping 2017 doesn’t bring any letdowns from beloved authors.

The Worst Book I Read This Year: Paulina & Fran (2015) by Rachel B. Glaser. My only one-star review of the year. ’Nuff said?

The 2016 Novels I Most Wish I’d Gotten to: (At least the 10 I’m most regretful about)

- The Power by Naomi Alderman

- The Museum of You by Carys Bray

- The Course of Love by Alain de Botton

- What Belongs to You by Garth Greenwell*

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi- The Waiting Room by Leah Kaminsky

- The Inseparables by Stuart Nadler

- Harmony by Carolyn Parkhurst*

- The Nest by Cynthia D’Aprix Sweeney*

- The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead*

*Haven’t been able to find anywhere yet; the rest are on my Kindle.

Which of these should I get reading on the double?

Coming tomorrow: Some reading goals for 2017.

How People Found My Blog Recently

Back in May I surveyed a few months’ worth of the (often very odd) web searches that led people to my blog. In the past four and a half months the search terms have been more normal in that they generally relate to books or authors I’ve covered. However, I do hope I haven’t disappointed some searchers: after all, I don’t reveal the exact location of the croft in Seal Morning, instruct readers in how to pronounce ‘Athill’, or give any details about Ann Kidd Taylor’s wedding!

In any case, it’s always interesting to see what people were looking up – Oliver Balch’s Under the Tump, Michel Faber’s Undying, Sarah Perry’s The Essex Serpent and various graphic novels were popular topics – and I reckon I count among the “bookish cat people” of the first search. (Spelling and punctuation are unedited throughout this list!)

May 26: bookish cat people, oliver balch under the tump

May 31: a book review of any book about 140-160 words, in my next life i want to be a cat. to sleep 20 hours a day and wait to be fed. to sit around licking my ass., under the tump by oliver balch reviews

June 25: irmina yelin, george watsky bipolar

July 2: michel faber undying goodreads, the first bad man book miranda july plot

July 16: she’s my only father’s daughter, essex serpent, sue gee, hay on wye

July 21: the ghost of nelly burdons beck

August 5: correct pronunciation of athill in diana athill s name

August 11: the essex serpent usa release

August 24: ann kidd taylor wedding

August 25: paintings with a woman reading a book

August 29: michel faber undying review, to the bright edge of the world interview

September 8: agatha christie graphic novel, house of hawthorne

September 13: irmina by barbara yellen

September 19: paulette bates

September 21: bbc miniseris vs book war and peace

September 26: vincent van gogh graphic novel

September 28: reviews on my son my sonby howard spring

September 30: seal morning location of croft

October 3: john pritchard_something more

The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry

This exquisite work of historical fiction explores the gaps – narrower than one might think – between science and superstition and between friendship and romantic love. The Essex Serpent was a real-life legend from the latter half of the seventeenth century, but Perry’s second novel has fear of the sea creature re-infecting Aldwinter, her invented Essex village, in the 1890s. Mysterious deaths and disappearances are automatically attributed to the Serpent who dwells in the depths of the Blackwater. This atmosphere of paranoia triggers some schoolgirls to erupt in frenzied delusions as in The Crucible. It is unclear whether the Church should tolerate a source of mystery or dismiss it all as nonsense – after all, there’s a winged serpent carved onto one of the pews at the parish church.

In a domestic counterpart to all these supernatural goings-on, we gain entry into two middle-class households. Cora Seaborne’s abusive husband, Michael, has recently died of throat cancer, leaving her to raise their odd (autistic, I wondered?) eleven-year-old son Francis on her own. She has an amateur interest in fossils to rival Mary Anning’s, so when she hears of a cache near Colchester she leaves London for Essex, bringing along Frankie and her companion, Martha. Mutual friends put her in touch with Will Ransome, the vicar of Aldwinter, sure that he and his family – consumptive wife Stella and children Joanna, James and John – will be able to show her around the coast.

In a domestic counterpart to all these supernatural goings-on, we gain entry into two middle-class households. Cora Seaborne’s abusive husband, Michael, has recently died of throat cancer, leaving her to raise their odd (autistic, I wondered?) eleven-year-old son Francis on her own. She has an amateur interest in fossils to rival Mary Anning’s, so when she hears of a cache near Colchester she leaves London for Essex, bringing along Frankie and her companion, Martha. Mutual friends put her in touch with Will Ransome, the vicar of Aldwinter, sure that he and his family – consumptive wife Stella and children Joanna, James and John – will be able to show her around the coast.

Despite an inauspicious first meeting, which sees Cora and Will, still unknown to each other, hauling a drowning sheep out of a lake, theirs soon becomes a close, easy friendship. Cora feels she can speak her mind about the faith she lost and the new marvels she finds in nature:

I had faith, the sort I think you might be born with, but I’ve seen what it does and I traded it in. It’s a sort of blindness, or a choice to be mad – to turn your back on everything new and wonderful – not to see that there’s no fewer miracles in the microscope than in the gospels!

She holds her own in cerebral debates with Will as he deplores his parishioners’ fantasies about the Serpent. Is there really such a big difference between his faith – “all strangeness and mystery – all blood, and brimstone,” Cora teases – and the Serpent legend? In seeming contradiction to his career path, Will is more suspicious than many of the other characters of things he doesn’t understand and can’t explain away, like hypnosis and a Fata Morgana.

The novel’s nuanced treatment of faith and doubt is enhanced by references to Victorian science, including fossil hunting and early medical procedures. Dr. Luke Garrett, Michael’s surgeon, is one of Cora’s best friends back in London; she calls him “The Imp.” In one of the most striking passages of the entire book, he performs rudimentary heart surgery on the young victim of a stab wound. Perry fills in the novel’s background with a plethora of apt Victorian themes, including housing reform and London crime. For a book of 440 pages, it has a large cast and a fairly epic scope. Although there are places where subplots and minor characters might have been expanded upon, Perry wisely refrains from stuffing the novel with evidence of her research. Indeed, it’s a restrained book overall, yet breaks out into effusiveness in just the right places, as in Stella’s mystical adoration of the color blue.

Descriptive passages and the letters passing between the characters give a clear sense of the months passing, yet there is also something timelessly English about the narrative – Dickensian in places (Our Mutual Friend) and Hardyesque in others (Far from the Madding Crowd). I especially loved this picture of the June countryside:

Essex has her bride’s gown on: there’s cow parsley frothing by the road and daisies on the common, and the hawthorn’s dressed in white; wheat and barley fatten in the fields, and bindweed decks the hedges.

Cross this cozy pastoral vision with the Gothic nature of the Serpent craze and you get quite a unique atmosphere. The vague, unexplained sense of menace didn’t work for me at all in Perry’s previous novel, After Me Comes the Flood, but here it’s just right.

It was no doubt true in the late Victorian period that “men and women can’t be friends because the sex part always gets in the way” (as famously declared in When Harry Met Sally). No one is sure what to make of a sexually available, self-assured female like Cora. The different kinds of Greek love, from philia to eros, keep shading into each other here. Like the water that forms the book’s metaphorical substrate, the relationships ebb and flow. Yet there’s no denigrating any connection as just friendship; in fact, friendship is enough to rescue one character from suicide. Like Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, the novel asks whether love is ever enough to save us – and gives a considerably more optimistic answer.

My proof copy didn’t have quite such a gorgeous cover but did come intriguingly wrapped in snakeskin ribbon…

The fact that I have an MA in Victorian literature means I’m drawn to Victorian-set novels but also highly critical about their authenticity. While reading this, though, I thoroughly believed that I was in 1890. Moreover, Perry adroitly illuminates the situation of the independent “New Woman” and the quandary of science versus religion (which were the joint subjects of my dissertation: women’s faith and doubt narratives in Victorian fiction).

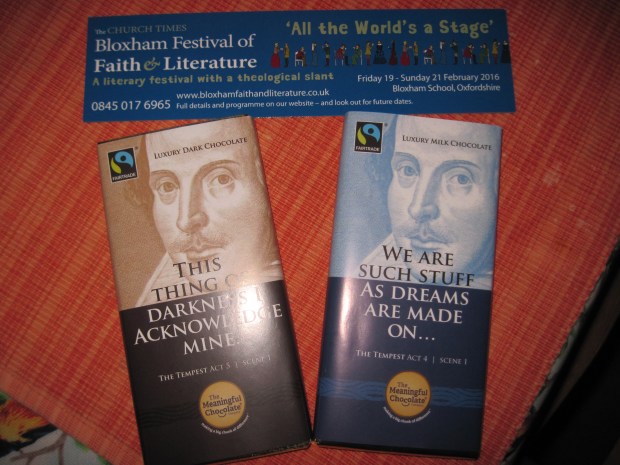

I’m delighted, especially having seen Perry speak at Bloxham Festival in February (see my write-up for more on her background and the inspirations behind this novel), to have liked The Essex Serpent three times as much as her debut. It has an elegant, evocative writing style reminiscent of A.S. Byatt and Penelope Fitzgerald. Something holds me back from the full 5 stars – too diffuse? Too much staying on the surface of things? Not quite intimate enough, especially about Cora’s inner life? – but I still declare myself mightily impressed. The Essex Serpent counts as one of my favorite novels of 2016 so far. You can see why Serpent’s Tail (how perfect is her publisher’s name?!) rushed this one into publication a few weeks early. Expect to see it on the Booker Prize shortlist and any other award list you care to mention.

With thanks to Anna-Marie Fitzgerald at Serpent’s Tail for the free review copy.

My rating:

The Longest Night by Andria Williams: This absorbing work of historical fiction combines a remote setting, the threat of nuclear fallout, and a marriage strained to the breaking point in a convincing early 1960s atmosphere. A great debut and an author I’d like to hear more from.

The Longest Night by Andria Williams: This absorbing work of historical fiction combines a remote setting, the threat of nuclear fallout, and a marriage strained to the breaking point in a convincing early 1960s atmosphere. A great debut and an author I’d like to hear more from.

Still the Animals Enter

Still the Animals Enter

And then there’s the books I’d simply never heard of. Of these I’m most interested in His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet, based on a true-life murder in Scotland in the 1860s, and The Many by Wyl Menmuir, a debut novella about a village newcomer.

And then there’s the books I’d simply never heard of. Of these I’m most interested in His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet, based on a true-life murder in Scotland in the 1860s, and The Many by Wyl Menmuir, a debut novella about a village newcomer.

After Me Comes the Flood was rejected by 14 publishers; even her viva examiners, who passed her without corrections, were “ungracious,” she remarked. What it comes down to, she thinks, is simply that no one liked the book or knew what to make of it. It seemed unmarketable because it didn’t fit into a particular genre. At this point I was sheepishly keeping my head down, glad that Perry couldn’t possibly know about my largely unfavorable review in Third Way magazine. I confess that my reaction was roughly similar to the general consensus: “Not quite an allegory, [the book] still suffers from that genre’s pitfalls, such as one-dimensional characters,” I wrote.

After Me Comes the Flood was rejected by 14 publishers; even her viva examiners, who passed her without corrections, were “ungracious,” she remarked. What it comes down to, she thinks, is simply that no one liked the book or knew what to make of it. It seemed unmarketable because it didn’t fit into a particular genre. At this point I was sheepishly keeping my head down, glad that Perry couldn’t possibly know about my largely unfavorable review in Third Way magazine. I confess that my reaction was roughly similar to the general consensus: “Not quite an allegory, [the book] still suffers from that genre’s pitfalls, such as one-dimensional characters,” I wrote. In the other sessions I attended, a group of clergy revealed the shortlist for the £10,000

In the other sessions I attended, a group of clergy revealed the shortlist for the £10,000  Chaired by contemporary Anglican novelist

Chaired by contemporary Anglican novelist