Young Writer of the Year Award Ceremony

Yesterday evening all of us on the Sunday Times / Peters Fraser + Dunlop Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel met up again for the official prize-giving ceremony at the London Library.

My train arrived late and then I got lost, twice (I don’t own a smartphone and hadn’t brought a map – foolish!), so I walked through the door just moments before the prize announcement, but as that was the most important part of the event it didn’t matter in the end. If you haven’t already heard, the prize went to Sally Rooney for Conversations with Friends. She’s the first Irish winner and the joint youngest along with Zadie Smith.

This did not really come as a surprise to the shadow panel, even though we unanimously chose Julianne Pachico’s The Lucky Ones as our winner.

Julianne Pachico is third from left.

Three of us had chosen Rooney’s novel as our runner-up, and when I saw it appear in the Times’ Books of the Year feature, I thought to myself that this was probably a clue. In the official press release, judge and Sunday Times literary editor Andrew Holgate writes, “for line by line quality, emotional complexity, sly sophistication and sheer brio and enjoyment, Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends really stood out.”

Judge Elif Shafak states, “I salute Rooney’s intelligent prose, lucid style, and fierce intensity.” Judge Lucy Hughes-Hallett says, “This book stood out for its glittering intelligence, its formal elegance and its capacity to grip the reader. At first reading I was looking forward to bus journeys so that I could read some more. Second time round I was still delighted by the sophistication of its erotic quadrille.”

Being a part of the shadow panel was a wonderful experience and one of the highlights of my literary year.

Talking ’bout My Generation? Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist review #2

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist review #2

The first thing to note about a novel with “Conversations” in the title is that there are no quotation marks denoting speech. In a book so saturated with in-person chats, telephone calls, texts, e-mails and instant messages, the lack of speech marks reflects the swirl of voices in twenty-one-year-old Frances’ head; thought and dialogue run together. This is a work in which communication is a constant struggle but words have lasting significance.

It’s the summer between years at uni in Dublin, and Frances is interning at a literary agency and collaborating with her best friend (and ex-girlfriend) Bobbi on spoken word poetry events. She’s the ideas person, and Bobbi brings her words to life. At an open mic night they meet Melissa, an essayist and photographer in her mid-thirties who wants to profile the girls. She invites them back for a drink and Frances, who is from a slightly rough background – divorced parents and an alcoholic father who can’t be relied on to send her allowance – is dazzled by the apparent wealth of Melissa and her handsome actor husband, Nick. Bobbi develops a crush on Melissa, and before too long Frances falls for Nick. The stage is set for some serious amorous complications over the next six months or so.

It’s the summer between years at uni in Dublin, and Frances is interning at a literary agency and collaborating with her best friend (and ex-girlfriend) Bobbi on spoken word poetry events. She’s the ideas person, and Bobbi brings her words to life. At an open mic night they meet Melissa, an essayist and photographer in her mid-thirties who wants to profile the girls. She invites them back for a drink and Frances, who is from a slightly rough background – divorced parents and an alcoholic father who can’t be relied on to send her allowance – is dazzled by the apparent wealth of Melissa and her handsome actor husband, Nick. Bobbi develops a crush on Melissa, and before too long Frances falls for Nick. The stage is set for some serious amorous complications over the next six months or so.

Young woman and older, married man: it may seem like a cliché, but Sally Rooney is doing a lot more here than just showing us an affair. For one thing, this is a coming of age in the truest sense: Frances, forced into independence for the first time, is figuring out who she is as she goes along and in the meantime has to play roles and position herself in relation to other people:

At any time I felt I could do or say anything at all, and only afterwards think: oh, so that’s the kind of person I am.

I couldn’t think of anything witty to say and it was hard to arrange my face in a way that would convey my sense of humour. I think I laughed and nodded a lot.

What will be her rock in the uncertainty? She can’t count on her parents; she alienates Bobbi as often as not; she reads the Gospels out of curiosity but finds no particular solace in religion. Her other challenge is coping with the chronic pain of a gynecological condition. More than anything else, this brings home to her the disappointing nature of real life:

I realised my life would be full of mundane physical suffering, and that there was nothing special about it. Suffering wouldn’t make me special, and pretending not to suffer wouldn’t make me special. Talking about it, or even writing about it, would not transform the suffering into something useful. Nothing would.

Rooney writes in a sort of style-less style that slips right down. There’s a flatness to Frances’ demeanor: she’s always described as “cold” and has trouble expressing her emotions. I recognized the introvert’s risk of coming across as aloof. Before I started this I worried that I’d fail to connect to a novel about experiences so different from mine. I was quite the strait-laced teen and married at 23, so I wasn’t sure I’d be able to relate to Frances and Bobbi’s ‘wildness’. But this is much more about universals than it is about particulars: realizing that you’re stuck with yourself, exploring your sexuality and discovering that sex is its own kind of conversation, and deciding whether ‘niceness’ is really the same as morality.

Rooney writes in a sort of style-less style that slips right down. There’s a flatness to Frances’ demeanor: she’s always described as “cold” and has trouble expressing her emotions. I recognized the introvert’s risk of coming across as aloof. Before I started this I worried that I’d fail to connect to a novel about experiences so different from mine. I was quite the strait-laced teen and married at 23, so I wasn’t sure I’d be able to relate to Frances and Bobbi’s ‘wildness’. But this is much more about universals than it is about particulars: realizing that you’re stuck with yourself, exploring your sexuality and discovering that sex is its own kind of conversation, and deciding whether ‘niceness’ is really the same as morality.

With its prominent dialogue and discrete scenes, I saw the book functioning like a minimalist play, and I could also imagine it working as an on-location television miniseries. In some ways the dynamic between Frances and Bobbi mirrors that between the main characters in Paulina and Fran by Rachel B. Glaser, Friendship by Emily Gould, and The Animators by Kayla Rae Whitaker, so if you enjoyed any of those I highly recommend this, too. Rooney really captures the angst of youth:

You’re twenty-one, said Melissa. You should be disastrously unhappy.

I’m working on it, I said.

This is a book I was surprised to love, but love it I did. Rooney is a tremendous talent whose career we’ll have the privilege to watch unfolding. I’ve told the shadow panel that if we decide our focus is on the “Young” in Young Writer, there’s no doubt that this nails the zeitgeist and should win.

The conversations even spill out onto the endpapers.

Reviews of Conversations with Friends:

From the shadow panel:

Annabel’s at Annabookbel

Clare’s at A Little Blog of Books

Dane’s at Social Book Shelves

Eleanor’s at Elle Thinks

Others:

On the Road with Ma: The Lauras by Sara Taylor

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist review #1

Sara Taylor’s debut, The Shore, was a gritty and virtuosic novel-in-13-stories that imagined 250 years of history on a set of islands off the coast of Virginia. It was one of my favorite books of 2015, and earned Taylor a spot on that year’s Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist as well as the Baileys Prize longlist. Her second book is a whole different kettle of fish: a fairly straightforward record of an extended North American road trip that 13-year-old Alex took with his/her mother 30 years ago.

Alex and Ma have run off from their home in Virginia and left Alex’s father behind. They travel, seemingly at random, all over – North Carolina, Michigan, Mississippi, Nevada, California – stopping for weeks at a time for Ma to earn enough to move on again. On the way they visit various sites from Ma’s past, mostly foster homes where she lived as a runaway teen and made fleeting connections with friends and lovers. Her five best friends were all apparently named Laura. Sometimes it seems Ma is after revenge; other times she’s making amends for mistakes from her past or attending to unfinished business. One thing gradually becomes clear: this is no arbitrary journey but a quest with a destination. It even has a Harold Fry element, though Taylor avoids Rachel Joyce’s schmaltz.

The Lauras is more complex than your average coming-of-age tale, largely because of Alex’s deliberate androgyny: a whole novel passes without us figuring out whether the narrator is male or female. “I suppose I was forgettable, came across still as whichever gender a person expected to see … being either and neither and both at once fit me more closely than the other options on offer,” Alex writes. But this chosen indeterminateness is not without consequences: there are a couple of disturbing scenes of bullying and sexual assault.

The Lauras is more complex than your average coming-of-age tale, largely because of Alex’s deliberate androgyny: a whole novel passes without us figuring out whether the narrator is male or female. “I suppose I was forgettable, came across still as whichever gender a person expected to see … being either and neither and both at once fit me more closely than the other options on offer,” Alex writes. But this chosen indeterminateness is not without consequences: there are a couple of disturbing scenes of bullying and sexual assault.

I enjoyed the mother-and-teen banter and the depiction of characters who are restless and rootless, driven on by traumatic memories as much as by uncertainty about the future. However, I had a few problems with the book. A road trip is generally a fun fictional setup, but here it tends towards the episodic and the repetitive. Moreover, Ma’s past is generally conveyed by secondhand stories rendered in Alex’s voice, which subordinates Ma’s perspective to her child’s and relies on somewhat dull reportage. Also, the metaphorical language and level of psychological understanding seem too advanced for a young teen, which only emphasizes the disjunction between the events being recounted (perhaps from the 1990s?) and the supposed present day three decades later. Those niggles explain why I abandoned this book a third of the way through on my first attempt in December 2016, and why, for me at least, it overall pales in comparison with the originality of The Shore.

I prefer this cover image.

Bearing in mind that I might be meeting these authors at the shortlist event or prize-giving ceremony, I’m not going to rate the five ST Young Writer books. (It wouldn’t take much sleuthing to find my Goodreads ratings, but never mind.) I’m still a huge fan of Sara Taylor’s work and look forward to her next book; were this to be the consensus of the rest of the shadow panel I would happily recognize it, but it’s unlikely to be one of my top two.

Other reviews of The Lauras:

Postscript: Taylor and I have a few neat connections: she graduated from Randolph College (formerly Randolph-Macon Women’s College), whose study abroad program in Reading, England brought me over here for the first time, and when not working on her PhD at UEA lives with her husband in Reading. Plus a tiny mention from The Lauras made me cheer: Ma went to Hood College, my alma mater!

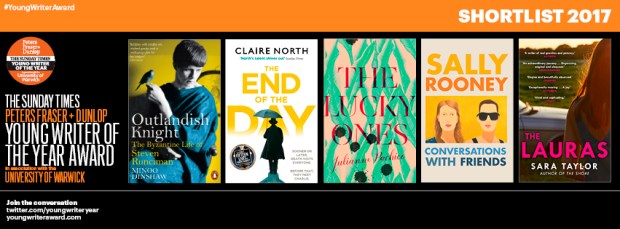

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel

I’m delighted to announce that I’ve been invited to be on the official shadow panel for the Sunday Times / Peters Fraser + Dunlop Young Writer of the Year Award, in association with The University of Warwick (to give it its full and proper title). Here’s a bit of background on the prize, from its website:

The prize “is awarded annually to the best work of published or self-published fiction, non-fiction or poetry by a British or Irish author aged between 18 and 35, and has gained attention and acclaim across the publishing industry and press. £5,000 is given to the overall winner and £500 to each of the three runners-up.

“Since it began in 1991, the award has had a striking impact, boasting a stellar list of alumni that have gone on to become leading lights of contemporary literature. The 2016 Award was presented to Max Porter for his extraordinary debut, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers. Following a five-year break, the prestigious award returned with a bang in 2015, awarding debut poet Sarah Howe the top prize for her phenomenal first collection, Loop of Jade.”

Past winners include Ross Raisin, Adam Foulds, Naomi Alderman, Robert Macfarlane, William Fiennes, Zadie Smith, Sarah Waters, Francis Spufford, Simon Armitage and Helen Simpson.

This year’s official judging panel is made up of Andrew Holgate, literary editor of the Sunday Times, and writers Lucy Hughes-Hallett and Elif Shafak.

I’m joined on the shadow panel by four other book bloggers, several of whom you will recognize as long-time friends of this blog:

- Dane Cobain (SocialBookshelves)

- Eleanor Franzen (Elle Thinks)

- Annabel Gaskell (Annabookbel)

- Clare Rowland (A Little Blog of Books)

Here are some key upcoming dates:

- Sunday October 29th: shortlist announced in Sunday Times

- November 18th: book bloggers event with readings from the shortlisted authors (Groucho Club, London)

- November 27th: deadline for shadow panel winner decision

- November 29th: shadow panel winner announced on STPFD website

- December 3rd: shadow panel winner announced in Sunday Times

- December 7th: prize-giving ceremony and winner announcement (London Library)

I’m so looking forward to getting stuck into the shortlisted books and discussing them! I’ll be posting a review of each one in November.

Wellcome Book Prize Shadow Panel Decision

It’s been a whirlwind five weeks as we on the shadow panel have made our way through the six books shortlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize 2017. The list is strong and varied: an account of the AIDS crisis, a posthumous memoir by a neurosurgeon, a thorough history of genetics, an introduction to the microbial world, and novels about a donor heart and an ordinary family’s encounter with unexpected illness. All have been well worth engaging with, but when it came to decision time we had a pretty clear winner: When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. (With Sarah Moss’s The Tidal Zone a fairly close second.)

“I realized that the questions intersecting life, death, and meaning, questions that all people face at some point, usually arise in a medical context.” ~Paul Kalanithi

I first read this book a year and a half ago; when I picked it back up on Friday, I thought I’d give it just a quick skim to remind myself why I loved it. Before I knew it I’d read 50 pages, and I finished it last night in the car on the way back from a family party, clutching my dinky phone as a flashlight, awash in tears once again. (To put this in perspective: I almost never reread books. My last rereading was of several Dickens novels for my master’s in 2005–6.)

What struck me most on my second reading is how Kalanithi, even in his brief life, saw both sides of the medical experience (as the U.K. book cover portrays so well). He was the harried neurosurgery resident making life and death decisions and marveling at the workings of the brain; in a trice he was the patient with terminal lung cancer wondering how to make the most of his remaining time with his family.

Yet in both roles his question was always “What makes human life meaningful?” – a quest that kept him shuttling between science, literature and religion. In eloquent prose and with frequent scriptural allusions, this short, technically unfinished book narrates Kalanithi’s past (his growing-up years and medical training), present (undergoing cancer treatment but ultimately facing death) and future (the legacy he leaves behind, including his daughter).

Looking back once again at the guidelines for the Wellcome Book Prize (“At some point, medicine touches all our lives. Books that find stories in those brushes with medicine are ones that add new meaning to what it means to be human”), When Breath Becomes Air stands out as a perfect exemplar. In her blog review, Ruby writes, “This book looks death right in the eye and doesn’t seek to rationalise it, explain it, avoid it. It deals with it head on.” In his Nudge review Paul calls the book “equally heart breaking and full of love … a painfully honest account of a short, but intense life.”

My thanks, once again, to the other members of the shadow panel: Paul Cheney, GrrlScientist, Ruby Jhita and Amy Pirt.

Tomorrow evening the winner of the Wellcome Book Prize 2017 will be announced at an awards ceremony at the Wellcome Collection in London. As thanks for my participation in the blog tour, I’ve been invited to attend. Small talk and networking are very much outside of my comfort zone, but I couldn’t pass up this opportunity and hope to at the very least meet one or two fellow bloggers. I’ll post very quickly when I get home from the ceremony tomorrow night to announce the winner, and promise a longer write-up of the event sometime on Tuesday.

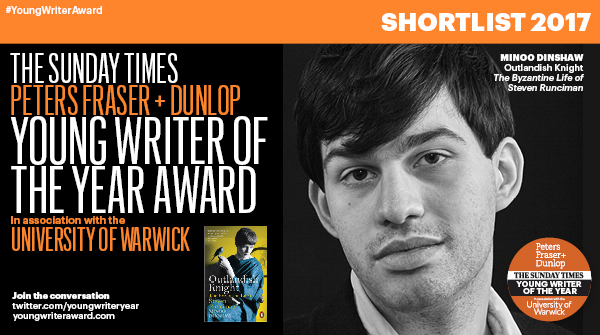

Dinshaw draws a fine distinction between his subject’s professional and private selves. When talking about the published historian and thinker, he uses “Runciman”; when talking about the closeted homosexual and his relationships with family and friends, it’s “Steven”. This confused me to start with, but quickly became second nature. Occasionally these public and private personas are contrasted directly: “Runciman was a great romantic historian; but in his personal affairs Steven had come to be more admiring of that epithet ‘realistic’ than of any height of romance.” Indeed, Steven once confessed he had never been in love. At the shortlist event on Saturday, Dinshaw summed him up as “an old-fashioned, courtly queer.”

Dinshaw draws a fine distinction between his subject’s professional and private selves. When talking about the published historian and thinker, he uses “Runciman”; when talking about the closeted homosexual and his relationships with family and friends, it’s “Steven”. This confused me to start with, but quickly became second nature. Occasionally these public and private personas are contrasted directly: “Runciman was a great romantic historian; but in his personal affairs Steven had come to be more admiring of that epithet ‘realistic’ than of any height of romance.” Indeed, Steven once confessed he had never been in love. At the shortlist event on Saturday, Dinshaw summed him up as “an old-fashioned, courtly queer.” Chapter titles are mainly taken from relevant tarot cards (for instance, Chapter 22, “The Hanged Man,” primarily concerns Steven’s homosexuality), which also feature on the book’s endpapers. The text is also partitioned by two sets of glossy black-and-white photographs. The book’s scope and the years of research that went into it cannot fail to impress. I never warmed to Steven as much as I wanted to, but that is likely due to a lack of engagement: regrettably, I had to skim much of the book to make the deadline. However, I will not be at all surprised if the official judges choose to honor this imposing work of scholarship.

Chapter titles are mainly taken from relevant tarot cards (for instance, Chapter 22, “The Hanged Man,” primarily concerns Steven’s homosexuality), which also feature on the book’s endpapers. The text is also partitioned by two sets of glossy black-and-white photographs. The book’s scope and the years of research that went into it cannot fail to impress. I never warmed to Steven as much as I wanted to, but that is likely due to a lack of engagement: regrettably, I had to skim much of the book to make the deadline. However, I will not be at all surprised if the official judges choose to honor this imposing work of scholarship.

I loved the premise of the novel, and its witty writing should appeal to Terry Pratchett and Nicola Barker fans. The more fantastical elements are generally brought back to earth by unremitting bureaucracy – I especially enjoyed a scene in which Charlie is questioned by U.S. Border officials. But the book’s structure and style got in the way for me. It is episodic and told via super-short chapters (110 of them). It skips around in a distracting manner, never landing on one scene or subplot for very long. Ellipses, partial repeated lines, and snippets of other voices all contribute to it feeling scattered and aimless. North’s

I loved the premise of the novel, and its witty writing should appeal to Terry Pratchett and Nicola Barker fans. The more fantastical elements are generally brought back to earth by unremitting bureaucracy – I especially enjoyed a scene in which Charlie is questioned by U.S. Border officials. But the book’s structure and style got in the way for me. It is episodic and told via super-short chapters (110 of them). It skips around in a distracting manner, never landing on one scene or subplot for very long. Ellipses, partial repeated lines, and snippets of other voices all contribute to it feeling scattered and aimless. North’s

Claire North, aka “Cat” (real name: Catherine Webb; her fantasy and science fiction books are under various names) was in a way the odd one out at this event. Collins opened by saying that this award is all about getting in on the ground level with these writers, several of whom are debut authors. But North is a teen phenom who published her first book at age 14 and is set to release #20 next year. All along her parents called her a freak and demanded that she get her GCSEs and go to uni because writing “isn’t a proper job” (“but we’re very proud of you!” they’d usually append). She’s experienced the full gamut of responses over the years: some swore she wouldn’t have anything to say until age 40; others sighed that once she turned 18 she could no longer be marketed as “young.” She read the perfect passage from The End of the Day: a frantic, bravura account of the riders of the apocalypse together on a plane. She loves that science fiction “makes the extraordinary domestic” and playing with death appealed to her “flippant nature.” Charlie is, she thinks, the kindest character she’s ever written.

Claire North, aka “Cat” (real name: Catherine Webb; her fantasy and science fiction books are under various names) was in a way the odd one out at this event. Collins opened by saying that this award is all about getting in on the ground level with these writers, several of whom are debut authors. But North is a teen phenom who published her first book at age 14 and is set to release #20 next year. All along her parents called her a freak and demanded that she get her GCSEs and go to uni because writing “isn’t a proper job” (“but we’re very proud of you!” they’d usually append). She’s experienced the full gamut of responses over the years: some swore she wouldn’t have anything to say until age 40; others sighed that once she turned 18 she could no longer be marketed as “young.” She read the perfect passage from The End of the Day: a frantic, bravura account of the riders of the apocalypse together on a plane. She loves that science fiction “makes the extraordinary domestic” and playing with death appealed to her “flippant nature.” Charlie is, she thinks, the kindest character she’s ever written. Sara Taylor read from one of Ma’s earliest stories about how her parents met. She wrote The Lauras while she was supposed to be completing her PhD thesis on censorship in American literature. At the time she was coming to terms with the fact that she was going to be staying in the UK, as well as remembering family road trips and aspects of her relationship with her mother that she wishes were otherwise. Her agent wasn’t comfortable with the focus on an “agender” character, but Taylor held firm. She’s used to ignoring the advice her (older, male) professors and advisors tend to give her. Instead, she gets tips from her ten-years-younger sister back in the States, who knows exactly how to “fix” her work. Taylor feels the USA is 5–10 years behind the UK on gender issues, and revealed that The Lauras is a response to the novel Love Child (1971) by Maureen Duffy. She has recently finished her third novel and hopes to get back into teaching since writing non-stop for nine months makes her “go a little funny.”

Sara Taylor read from one of Ma’s earliest stories about how her parents met. She wrote The Lauras while she was supposed to be completing her PhD thesis on censorship in American literature. At the time she was coming to terms with the fact that she was going to be staying in the UK, as well as remembering family road trips and aspects of her relationship with her mother that she wishes were otherwise. Her agent wasn’t comfortable with the focus on an “agender” character, but Taylor held firm. She’s used to ignoring the advice her (older, male) professors and advisors tend to give her. Instead, she gets tips from her ten-years-younger sister back in the States, who knows exactly how to “fix” her work. Taylor feels the USA is 5–10 years behind the UK on gender issues, and revealed that The Lauras is a response to the novel Love Child (1971) by Maureen Duffy. She has recently finished her third novel and hopes to get back into teaching since writing non-stop for nine months makes her “go a little funny.”

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist review #3

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist review #3 Seven of the stories are in the third person, but others add in some interesting variety: in “Siberian Tiger Park,” the third graders of Stephanie’s class form a first-person plural voice as they set their vivid imaginations loose on the playground and turn against their former ringleader, and “The Bird Thing,” a slice of horror in which a maid’s traumatic memories feed a monster, is told in the second person. And then there’s “Junkie Rabbit,” a first-person story set among a coca-consuming colony of pet rabbits gone feral. It’s Watership Down on speed. Indeed, drug use and wildness are recurring tropes, and there’s a hallucinatory quality to these stories – somewhere between languid and frantic – that suits the subject matter.

Seven of the stories are in the third person, but others add in some interesting variety: in “Siberian Tiger Park,” the third graders of Stephanie’s class form a first-person plural voice as they set their vivid imaginations loose on the playground and turn against their former ringleader, and “The Bird Thing,” a slice of horror in which a maid’s traumatic memories feed a monster, is told in the second person. And then there’s “Junkie Rabbit,” a first-person story set among a coca-consuming colony of pet rabbits gone feral. It’s Watership Down on speed. Indeed, drug use and wildness are recurring tropes, and there’s a hallucinatory quality to these stories – somewhere between languid and frantic – that suits the subject matter.