Nonfiction November: Two Memoirs of Biblical Living by Evans and Jacobs

I love a good year-challenge narrative and couldn’t resist considering these together because of the shared theme. Sure, there’s something gimmicky about a rigorously documented attempt to obey the Bible’s literal commandments as closely as possible in the modern day. But these memoirs arise from sincere motives, take cultural and theological matters seriously, and are a lot of fun to read.

The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible by A.J. Jacobs (2007)

Jacobs came up with the idea, so I’ll start with him. His first book, The Know-It-All, was about absorbing as much knowledge as possible by reading the encyclopaedia. This starts in similarly intellectual fashion with a giant stack of Bible translations and commentaries. From one September to the next, Jacobs vows, he’ll do his best to understand and implement commandments from both the Old and New Testaments. It’s not a completely random choice of project in that he’s a secular Jew (“I’m Jewish in the same way the Olive Garden is an Italian restaurant. Which is to say: not very.”). Firstly, and most obviously, he stops shaving and getting haircuts. “As I write this, I have a beard that makes me resemble Moses. Or Abe Lincoln. Or [Unabomber] Ted Kaczynski. I’ve been called all three.” When he also takes to wearing all white, he really stands out on the New York subway system. Loving one’s neighbour isn’t easy in such an antisocial city, but he decides to try his best.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

The book is a near-daily journal, with a new rule or three grappled with each day. There are hundreds of strange and culturally specific guidelines, but the heart issues – covetousness, lust – pose more of a challenge. Alongside his work as a journalist for Esquire and this project, Jacobs has family stuff going on: IVF results in his wife’s pregnancy with twin boys. Before they become a family of five, he manages to meet some Amish people, visit the Creation Museum, take a trip to the Holy Land to see a long-lost uncle, and engage in conversation with Evangelicals across the political spectrum, from Jerry Falwell’s megachurch to Tony Campolo (who died just last week). Jacobs ends up a “reverent agnostic.” We needn’t go to such extremes to develop the gratitude he feels by the end, but it sure is a hoot to watch him. This has just the sort of amusing, breezy yet substantial writing that should engage readers of Bill Bryson, Dave Gorman and Jon Ronson. (Free mall bookshop) ![]()

A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband “Master” by Rachel Held Evans (2012)

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

It’s a sweet, self-deprecating book. You can definitely tell that she was only 29 at the time she started her project. It’s okay with me that Evans turned all her literal intentions into more metaphorical applications by the end of the year. She concludes that the Church has misused Proverbs 31: “We abandoned the meaning of the poem by focusing on the specifics, and it became just another impossible standard by which to measure our failures. We turned an anthem into an assignment, a poem into a job description.” Her determination is not to obsess over rules but to continue with the habits that benefited her spiritual life, and to champion women whenever she can. I suspect this is a lesser entry from Evans’s oeuvre. She died too soon – suddenly in 2019, of brain swelling after a severe allergic reaction to an antibiotic – but remains a valued voice, and I’ll catch up on the rest of her books. Searching for Sunday, for instance, was great, and I’m keen to read Evolving in Monkey Town (about living in Dayton, Tennessee, where the famous Scopes Monkey Trial took place). (Birthday gift from my wish list, 2023) ![]()

Blog Tour Review: Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? by Lev Parikian

Lev Parikian was a keen birdwatcher when he was 11, but as an adult he barely remembered most of what he used to know about birds. He’d confidently declare that he’d seen a nightingale and then be too embarrassed to later admit it was actually a skylark. Also, he had to acknowledge that he hadn’t been completely honest as a preteen birder: No way had he seen a black redstart, for instance. Probably about 30% of his childhood sightings could be dismissed as cheats or downright lies. As the birdwatching bug bit again at the start of 2016, he decided it was time to set the record straight. His aim? To see 200 birds in a year, with no twitching (driving many miles to see a reported rarity) and no cheating.

Lev Parikian was a keen birdwatcher when he was 11, but as an adult he barely remembered most of what he used to know about birds. He’d confidently declare that he’d seen a nightingale and then be too embarrassed to later admit it was actually a skylark. Also, he had to acknowledge that he hadn’t been completely honest as a preteen birder: No way had he seen a black redstart, for instance. Probably about 30% of his childhood sightings could be dismissed as cheats or downright lies. As the birdwatching bug bit again at the start of 2016, he decided it was time to set the record straight. His aim? To see 200 birds in a year, with no twitching (driving many miles to see a reported rarity) and no cheating.

Most of the book is a chronological tour through 2016, with each month’s new sightings totaled up at the end of the chapter. Being based in London isn’t the handicap one might expect – there’s a huge population of parakeets there nowadays, and the London Wetland Centre in Barnes is great for water birds – but Parikian also fills in his list through various trips around the country. He picks up red kites while in Windsor for a family wedding, and his list balloons in April thanks to trips to Minsmere and Rainham Marshes, where he finds additions like bittern and marsh harrier. The Isle of Wight, Scotland, Lindsifarne, North Norfolk… The months pass and the numbers mount until it’s the middle of December and his total is hovering at 196. Will he make it? I wouldn’t dare spoil the result for you!

I’ve always enjoyed ‘year-challenge’ books, everything from Julie Powell’s Julie and Julia to Nina Sankovitch’s Tolstoy and the Purple Chair, so I liked this memoir’s air of self-imposed competition, and its sense of humor. Having accompanied my husband on plenty of birdwatching trips, I could relate to the alternating feelings of elation and frustration. I also enjoyed the mentions of Parikian’s family history and career as a freelance conductor – I’d like to read more about this in his first book, Waving, Not Drowning (2013). This is one for fans of Alexandra Heminsley’s Leap In and Kyo Maclear’s Birds Art Life, or for anyone who needs reassurance that it’s never too late to pick up a new skill or return to a beloved hobby.

Lastly, I must mention what a beautiful physical object this book is. The good folk of Unbound have done it again. The cover image and endpapers reproduce Alan Harris’s lovely sketch of a gradually disappearing goldcrest, and if you lift the dustjacket you’re rewarded with the sight of some cheeky bird footprints traipsing across the cover.

Some favorite passages:

“Birders love a list. Day lists, week lists, month lists, year lists, life lists, garden lists, county lists, walk-to-work lists, seen-from-the-train lists, glimpsed-out-of-the-bathroom-window-while-doing-a-poo lists.”

“It’s one thing sitting in your favourite armchair, musing on the plumage differences between first- and second-winter black-headed gulls, but that doesn’t help identify the scrubby little blighter that’s just jigged into that bush, never to be seen again. And it’s no use asking them politely to damn well sit still blast you while I jot down the distinguishing features of your plumage in this notebook dammit which pocket is it in now where did I put the pencil ah here it is oh bugger it’s gone. They just won’t. Most disobliging.”

“There is a word in Swedish, gökotta, for the act of getting up early to listen to birdsong, but the knowledge that this word exists, while heartwarming, doesn’t make it any easier. It’s a bitter pill, this early rising, but my enthusiasm propels me to acts of previously unimagined heroism, and I set the alarm for an optimistic 5 a.m., before reality prompts me to change it to 5.15, no 5.30, OK then 5.45.”

My rating:

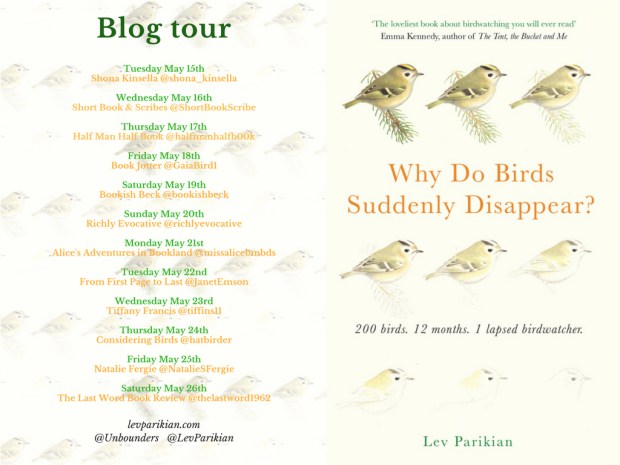

Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? was published by Unbound on May 17th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

I was delighted to be invited to participate in the blog tour for Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon (including on my hubby’s blog on Thursday!).

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths.

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths. A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was

A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was  From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.” I’ve been reading up a storm in 2021, of course, but I’m having an unusual problem: I can’t seem to finish anything. Okay, I’ve finished three books so far –

I’ve been reading up a storm in 2021, of course, but I’m having an unusual problem: I can’t seem to finish anything. Okay, I’ve finished three books so far –  Spinster by Kate Bolick: Written as she was approaching 40, this is a cross between a memoir, a social history of unmarried women (mostly in the USA), and a group biography of five real-life heroines who convinced her it was alright to not want marriage and motherhood. First was Maeve Brennan; now I’m reading about Neith Boyce. The writing is top-notch.

Spinster by Kate Bolick: Written as she was approaching 40, this is a cross between a memoir, a social history of unmarried women (mostly in the USA), and a group biography of five real-life heroines who convinced her it was alright to not want marriage and motherhood. First was Maeve Brennan; now I’m reading about Neith Boyce. The writing is top-notch. America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo: Set in the 1990s in the Philippines and in the Filipino immigrant neighborhoods of California, this novel throws you into an unfamiliar culture and history right at the deep end. The characters shine and the story is complex and confident – I’m reminded especially of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s work.

America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo: Set in the 1990s in the Philippines and in the Filipino immigrant neighborhoods of California, this novel throws you into an unfamiliar culture and history right at the deep end. The characters shine and the story is complex and confident – I’m reminded especially of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s work. Some Body to Love by Alexandra Heminsley: Finally pregnant after a grueling IVF process, Heminsley thought her family was perfect. But then her husband began transitioning. This is not just a memoir of queer family-making, but, as the title hints, a story of getting back in touch with her body after an assault and Instagram’s obsession with exercise perfection.

Some Body to Love by Alexandra Heminsley: Finally pregnant after a grueling IVF process, Heminsley thought her family was perfect. But then her husband began transitioning. This is not just a memoir of queer family-making, but, as the title hints, a story of getting back in touch with her body after an assault and Instagram’s obsession with exercise perfection. The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard: We’re reading the first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles for a supplementary book club meeting. I can hardly believe it was published in 1990; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of 1937‒8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex as war approaches. It’s so Downton Abbey; I love it and will continue the series.

The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard: We’re reading the first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles for a supplementary book club meeting. I can hardly believe it was published in 1990; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of 1937‒8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex as war approaches. It’s so Downton Abbey; I love it and will continue the series. Outlawed by Anna North: After Reese Witherspoon chose it for her book club, there’s no chance you haven’t heard about this one. I requested it because I’m a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, but I’m also enjoying this alternative history/speculative take on the Western. It’s very Handmaid’s, with a fun medical slant.

Outlawed by Anna North: After Reese Witherspoon chose it for her book club, there’s no chance you haven’t heard about this one. I requested it because I’m a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, but I’m also enjoying this alternative history/speculative take on the Western. It’s very Handmaid’s, with a fun medical slant. Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud: It was already on my TBR after the

Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud: It was already on my TBR after the

Banana Skin Shoes, Badly Drawn Boy – His best since his annus mirabilis of 2002. Funky pop gems we’ve been caught dancing to by people walking past the living room window … oops! A track to try: “

Banana Skin Shoes, Badly Drawn Boy – His best since his annus mirabilis of 2002. Funky pop gems we’ve been caught dancing to by people walking past the living room window … oops! A track to try: “ Where the World Is Thin, Kris Drever – You may know him from Lau. Top musicianship and the most distinctive voice in folk. Nine folk-pop winners, including a lockdown anthem. A track to try: “

Where the World Is Thin, Kris Drever – You may know him from Lau. Top musicianship and the most distinctive voice in folk. Nine folk-pop winners, including a lockdown anthem. A track to try: “ Henry Martin, Edgelarks – Mention traditional folk and I’ll usually run a mile. But the musical skill and new arrangements, along with Hannah Martin’s rich alto, hit the spot. A track to try: “

Henry Martin, Edgelarks – Mention traditional folk and I’ll usually run a mile. But the musical skill and new arrangements, along with Hannah Martin’s rich alto, hit the spot. A track to try: “ Blindsided, Mark Erelli – We saw him perform the whole of his new folk-Americana album live in lockdown. Love the Motown and Elvis influences; his voice is at a peak. A track to try: “

Blindsided, Mark Erelli – We saw him perform the whole of his new folk-Americana album live in lockdown. Love the Motown and Elvis influences; his voice is at a peak. A track to try: “ American Foursquare, Denison Witmer – A gorgeous ode to family life in small-town Pennsylvania from a singer-songwriter whose career we’ve been following for upwards of 15 years. A track to try: “

American Foursquare, Denison Witmer – A gorgeous ode to family life in small-town Pennsylvania from a singer-songwriter whose career we’ve been following for upwards of 15 years. A track to try: “

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.

now

now The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.  then /

then /  I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.