First Encounter: Karl Ove Knausgaard

For years I felt behind the curve because I had not yet read the two prime examples of European autofiction: Elena Ferrante and Karl Ove Knausgaard. It seemed like everyone was raving about them, calling their work revelatory and even compulsive (Zadie Smith has famously likened Knausgaard’s autobiographical novels to literary “crack”). Well, my first experience of Ferrante (see my review of My Brilliant Friend), about this time last year, was underwhelming, so that tempered my enthusiasm for trying Knausgaard. However, I had a copy of A Death in the Family on the shelf that I’d bought with a voucher, so I was determined to give him a go.

For years I felt behind the curve because I had not yet read the two prime examples of European autofiction: Elena Ferrante and Karl Ove Knausgaard. It seemed like everyone was raving about them, calling their work revelatory and even compulsive (Zadie Smith has famously likened Knausgaard’s autobiographical novels to literary “crack”). Well, my first experience of Ferrante (see my review of My Brilliant Friend), about this time last year, was underwhelming, so that tempered my enthusiasm for trying Knausgaard. However, I had a copy of A Death in the Family on the shelf that I’d bought with a voucher, so I was determined to give him a go.

I read this first part of the six-volume “My Struggle” series over the course of about two months. That’s much longer than I generally spend with a book, and unfortunately reflects the fact that it was the opposite of compelling for me; at times I had to force myself to pick it up from a stack of far more inviting books and read just five or 10 pages so I’d see some progress. Now, a couple of weeks after finally reading the last page, I can say that I’m glad I tried Knausgaard to see what the fuss is all about, but I think it unlikely that I’ll read any of his other books.

Written in 2008, when he was 39, this is Knausgaard’s record of his childhood and adolescence – specifically his relationship with his father, a distant and sometimes harsh man who drank himself to an early death. And yet at least half the book is about other things, with the father – whether alive or dead – as just a shadow in the background. I found it so curious what Knausgaard chooses to focus on in painstaking detail versus what he skates over.

For instance, he spends ages on the preparations for a New Year’s Eve party he attended in high school: acquiring the booze, the lengths he had to go to in hiding it and lugging it through a snowy night, and so on. He gives a broader idea of his school years through some classroom scenes and word pictures of friends he was in an amateur rock band with and girls he had crushes on, but these are very brief compared to the 50 pages allotted to the party.

Part Two feels like a significant improvement. It opens at the time of composition, with Karl Ove the writer and family man in his office in Sweden – a scene we briefly saw around 30 pages into Part One. I like these interludes perhaps best of all because they make a space for his philosophical musings about writing and parenthood:

Even if the feeling of happiness [fatherhood] gives me is not exactly a whirlwind but closer to satisfaction or serenity, it is happiness all the same. Perhaps, even, at certain moments, joy. And isn’t that enough? Isn’t it enough? Yes, if joy had been the goal it would have been enough. But joy is not my goal, never has been, what good is joy to me? The family is not my goal, either. … The question of happiness is banal, but the question that follows is not, the question of meaning.

Writing is drawing the essence of what we know out of the shadows. That is what writing is about. Not what happens there, not what actions are played out there, but the there itself.

At about the book’s halfway point we finally delve into the title event. About a decade previously Karl Ove got a call from his older brother, Yngve, telling him that their father was dead. Almost instantly he found himself trying to construct a narrative around this fact, assessing his thoughts to see if they had the appropriate gravity:

this is a big, big event, it should fill me to the hilt, but it isn’t doing that, for here I am, staring at the kettle, annoyed that it hasn’t boiled yet. Here I am, looking out and thinking how lucky we were to get this flat … and not that dad’s dead, even though that is the only thing that actually has any meaning.

Karl Ove Knausgaard at Turku Book Fair, 2011. By Soppakanuuna (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons.

What puzzles me, once again, is Knausgaard’s fixation on detail. He describes every meal he and Yngve shared with their grandmother, their every conversation, what he ate, how he slept, what he wore, what he cleaned and how and when. How could he possibly remember all of this, unless the journal that he mentions keeping at the time was truly exhaustive? And why does it all matter anyway? Does this slavish recreation fulfill the same role that obsessive action did back then: displacing his feelings about his father?

This is all the more unusual to me given the numerous asides where the author/narrator denigrates his memory:

I remembered hardly anything from my childhood. That is, I remembered hardly any of the events in it. But I did remember the rooms where they took place.

nostalgia is not only shameless, it is also treacherous. What does anyone in their twenties really get out of a longing for their childhood years? For their own youth? It was like an illness.

Now I had burned all the diaries and notes I had written, there was barely a trace of the person I was until I turned twenty-five, and rightly so; no good ever came out of that place.

Why did I remember this so well? I usually forgot almost everything people, however close they were, said to me.

The best explanation I can come up with is that this is not a work of memory. It’s more novel than it is autobiography. It’s very much a constructed object. Early in Part Two he reveals that when he first tried writing about his father’s death he realized he was too close to it; he had to step back and “force [it] into another form, which of course is a prerequisite for literature.” Style and theme, he believes, should take a backseat to form.

Ultimately, then, I think of this book as an experiment in giving a literary form to his father’s life and death, which affected him more than he’d ever, at least consciously, acknowledged. Even if I found the narrative focus strange at times, I recognize that it makes for precise vision: I could clearly picture each scene in my head, most taking place in an airy house with wood paneling and shag pile carpeting matching its 1970s décor. Maybe what I’m saying is: this would make a brilliant film, but I don’t think I have the patience for the rest of the books.

My rating:

Whether or not you’ve read Knausgaard, do you grasp his appeal? Should I persist with his books?

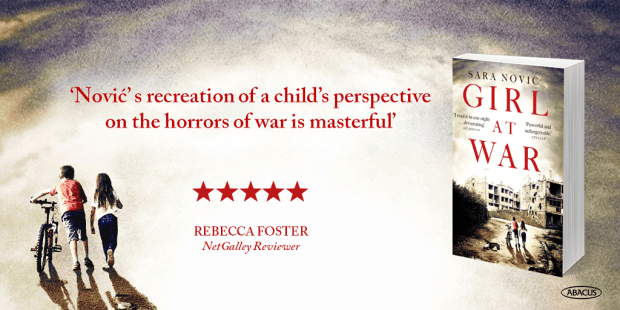

Girl at War Paperback Release

Next Thursday, the 24th, marks the UK paperback publication of Girl at War by Sara Nović, which I reviewed last year for BookBrowse (a subscription-only site, but you can see an excerpt of my review here). It was #3 on my list of last year’s best fiction, so I’m delighted that Little, Brown Book Group got in touch asking me to help publicize the paperback release. They created a shareable image with a snippet of my NetGalley feedback.

This pitch-perfect debut novel is an inside look at the Yugoslavian Civil War and its aftermath, from the perspective of a young girl caught up in the fighting. If you haven’t already read it, I encourage you to seek it out soon.

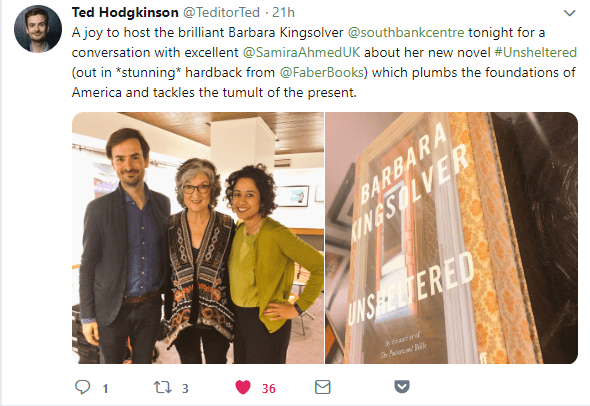

In person Kingsolver was a delight – warm and funny, with a generic American accent that doesn’t betray her Kentucky roots. In her beaded caftan and knee-high oxblood boots, she exuded girlish energy despite the shock of white in her hair. Although her fervor for the scientific method and a socially responsible government came through clearly, there was a lightness about her that tempered the weighty issues she covers in her novel.

In person Kingsolver was a delight – warm and funny, with a generic American accent that doesn’t betray her Kentucky roots. In her beaded caftan and knee-high oxblood boots, she exuded girlish energy despite the shock of white in her hair. Although her fervor for the scientific method and a socially responsible government came through clearly, there was a lightness about her that tempered the weighty issues she covers in her novel.

) and have also been moderating their online book club discussion of it. It’s been fascinating to see the spread of opinions, especially in the thread asking readers to describe the novel in three words. Descriptors have ranged from “preachy,” “political” and “repressive” to “prophetic,” “hopeful” and “truth.” My own three-word summary was “Bold, complex, polarizing.” I sensed that Kingsolver was going to divide readers – American ones, anyway; British readers should be a lot more positive because even centrist politics here start significantly further left, and there is for the most part very little resistance to concepts like socialism and climate change. I have a feeling the site’s users are predominantly middle-class, middle-aged white ladies (which, to be fair, was also true of the London audience), and we know that they’re a bastion of Trump support.

) and have also been moderating their online book club discussion of it. It’s been fascinating to see the spread of opinions, especially in the thread asking readers to describe the novel in three words. Descriptors have ranged from “preachy,” “political” and “repressive” to “prophetic,” “hopeful” and “truth.” My own three-word summary was “Bold, complex, polarizing.” I sensed that Kingsolver was going to divide readers – American ones, anyway; British readers should be a lot more positive because even centrist politics here start significantly further left, and there is for the most part very little resistance to concepts like socialism and climate change. I have a feeling the site’s users are predominantly middle-class, middle-aged white ladies (which, to be fair, was also true of the London audience), and we know that they’re a bastion of Trump support.

Frank and tender, this is a wonderful memoir about women’s reproductive choices – or the way life sometimes takes those choices out of your hands. Alden was happily married, with a beloved cat named Cecil and her first short story collection coming out soon. At age 39, she still hadn’t thought all that much about motherhood, but suddenly decision time was on her. Despite her ambivalence (“I might never have a child, and the irony is not lost on me, that I’m not even sure I want one”), she went ahead with multiple rounds of infertility treatment, only conceding defeat and grieving her loss when she was 42.

Frank and tender, this is a wonderful memoir about women’s reproductive choices – or the way life sometimes takes those choices out of your hands. Alden was happily married, with a beloved cat named Cecil and her first short story collection coming out soon. At age 39, she still hadn’t thought all that much about motherhood, but suddenly decision time was on her. Despite her ambivalence (“I might never have a child, and the irony is not lost on me, that I’m not even sure I want one”), she went ahead with multiple rounds of infertility treatment, only conceding defeat and grieving her loss when she was 42.