Wellcome Book Prize Blog Tour: Will Eaves’s Murmur

“This is the death of one viewpoint, and its rebirth, like land rising above the waves, or sea foam running off a crowded deck: the odd totality of persons each of whom says ‘me’.”

When I first tried reading Murmur, I enjoyed the first-person “Part One: Journal,” which was originally a stand-alone story (shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award 2017) but got stuck on “Part Two: Letters and Dreams” and ended up just giving the rest of the book a brief skim. I’m glad that the book’s shortlisting prompted me to return to it and give it proper consideration because, although it was a challenge to read, it was well worth it.

Eaves’s protagonist, Alec Pryor, sometimes just “the scientist,” is clearly a stand-in for Alan Turing, quotes from whom appear as epigraphs heading most chapters. Turing was a code-breaker and early researcher in artificial intelligence at around the time of the Second World War, but was arrested for homosexuality and subjected to chemical castration. Perhaps due to his distress at his fall from grace and the bodily changes that his ‘treatment’ entailed, he committed suicide at age 41 – although there are theories that it was an accident or an assassination. If you’ve read about the manner of his death, you’ll find eerie hints in Murmur.

Every other week, Alec meets with Dr Anthony Stallbrook, a psychoanalyst who encourages him to record his dreams and feelings. This gives rise to the book’s long central section. As is common in dreams, people and settings whirl in and out in unpredictable ways, so we get these kinds of flashes: sneaking out from the boathouse at night with his schoolboy friend, Chris Molyneux, who died young; anti-war protests at Cambridge; having sex with men; going to a fun fair; confrontations with his mother and brother; and so on. Alec and his interlocutors discuss the nature of time, logic, morality, and the threat of war.

There are repeated metaphors of mirrors, gold and machines, and the novel’s language is full of riddles and advanced vocabulary (volutes, manumitted, pseudopodium) that sometimes require as much deciphering as Turing’s codes. The point of view keeps switching, too, as in the quote I opened with: most of the time the “I” is Alec, but sometimes it’s another voice/self observing from the outside, as in Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater. There are also fragments of second- and third-person narration, as well as imagined letters to and from June Wilson, Alec’s former Bletchley Park colleague and fiancée. All of these modes of expression are ways of coming to terms with the past and present.

I am usually allergic to any book that could be described as “experimental,” but I found Murmur’s mosaic of narrative forms an effective and affecting way of reflecting its protagonist’s identity crisis. There were certainly moments where I wished this book came with footnotes, or at least an Author’s Note that would explain the basics of Turing’s situation. (Is Eaves assuming too much about readers’ prior knowledge?) For more background I recommend The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Turing.

I am usually allergic to any book that could be described as “experimental,” but I found Murmur’s mosaic of narrative forms an effective and affecting way of reflecting its protagonist’s identity crisis. There were certainly moments where I wished this book came with footnotes, or at least an Author’s Note that would explain the basics of Turing’s situation. (Is Eaves assuming too much about readers’ prior knowledge?) For more background I recommend The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Turing.

To my surprise, given my initial failure to engage with Murmur, it is now my favorite to win the Wellcome Book Prize. For one thing, it’s a perfect follow-on from last year’s winner, To Be a Machine. (“It is my fate to make machines that think,” Alec writes.) For another, it connects the main themes of this year’s long- and shortlists: mental health and sexuality. In particular, Alec’s fear that in developing breasts he’s becoming a sexual hybrid echoes the three books from the longlist that feature trans issues. Almost all of the longlisted books could be said to explore the mutability of identity to some extent, but Murmur is the very best articulation of that. A playful, intricate account of being in a compromised mind and body, it’s written in arresting prose. Going purely on literary merit, this is my winner by a mile.

My rating:

With thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review.

From Gallop: Selected Poems by Alison Brackenbury. Originally published in the volume After Beethoven.

Will Eaves is an associate professor in the Writing Programme at the University of Warwick and a former arts editor of the Times Literary Supplement. Murmur, his fourth novel, was also shortlisted for the 2018 Goldsmiths Prize and was the joint winner of the 2019 Republic of Consciousness Prize. He has also published poetry and a hybrid memoir.

Opinions on this book vary within our shadow panel; our final votes aren’t in yet, so it remains to be seen who we will announce as our winner on the 29th.

If you are within striking distance of London, please consider coming to the “5×15” shortlist event being held next Tuesday evening the 30th.

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the Wellcome Book Prize blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

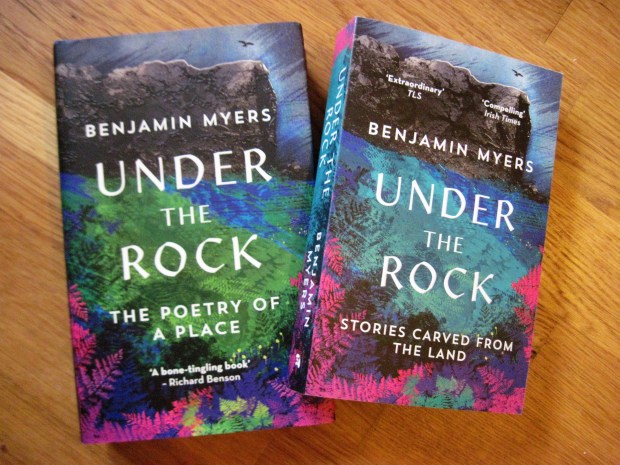

Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers: Paperback Giveaway

Benjamin Myers’s Under the Rock was my nonfiction book of 2018, so I’m delighted to be kicking off the blog tour for its paperback release on the 25th (with a new subtitle, “Stories Carved from the Land”). I’m reprinting my Shiny New Books review below, with permission, and on behalf of Elliott & Thompson I am also hosting a giveaway of a copy of the paperback. Leave a comment saying that you’d like to win and I will choose one entry at random at the end of the day on Tuesday the 30th. (Sorry, UK only.)

My review:

Benjamin Myers has been having a bit of a moment. In 2017 Bluemoose Books published his fifth novel, The Gallows Pole, which went on to win the Roger Deakin Award and the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction and is now on its fourth printing. This taste of fame has brought renewed attention to his earlier work, including Beastings (2014), recipient of the Northern Writers’ Award. I’ve been interested in Myers’s work ever since I read an extract from the then-unpublished The Gallows Pole in Autumn, the Wildlife Trusts anthology edited by Melissa Harrison, but this is the first of his books that I’ve managed to read.

“Unremarkable places are made remarkable by the minds that map them,” Myers writes, and that is certainly true of Scout Rock, a landmark overlooking Mytholmroyd, near where the author lives in the Calder Valley of West Yorkshire. When he moved up there from London over a decade ago, he and his wife lived in a rental cottage built in 1640. He approached his new patch with admirable curiosity, and supplemented the observations he made from his study window with frequent long walks with his dog, Heathcliff (“Walking is writing with your feet”), and research into the history of the area. The result is a divagating, lyrical book that ranges from geology to true crime but has an underlying autobiographical vein.

Ted Hughes was born nearby, the Brontës not that much further away, and Hebden Bridge, in particular, has become a bastion of avant-garde artists and musicians. Myers also gets plenty of mileage out of his eccentric neighbours and postman. It’s a town that seems to attract oddballs and renegades, from the vigilantes who poisoned the fishing hole to an overdose victim who turns up beneath a stand of Himalayan balsam. A strange preponderance of criminals has come from the region, too, including sexual offenders like Jimmy Savile and serial killers such as the Yorkshire Ripper and Harold Shipman (‘Doctor Death’).

On his walks Myers discovers the old town tip, still full of junk that won’t biodegrade for hundreds more years, and finds traces of the asbestos that was dumped by Acre Mill, creating a national scandal. This isn’t old-style nature writing in search of a few remaining unspoiled places. Instead, it’s part of a growing literary interest in the ‘edgelands’ between settlement and the wild – places where the human impact is undeniable but nature is creeping back in. (Other recent examples would be Common Ground by Rob Cowen, Landfill by Tim Dee, Edgelands by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, and Outskirts by John Grindrod.)

Under the Rock gives a keen sense of the seasons’ change and the seemingly inevitable melancholy that accompanies bad weather. A winter of non-stop rain left Myers nigh on delirious with flu; Storm Eva caused the Calder River to flood. He was a part of the effort to rescue trapped pensioners. Heartening as it is to see how the disaster brought people together – Sikh and Muslim charities and Syrian refugees were among the first to help – looting also resulted. One of the most remarkable things about this book is how Myers takes in such extremes of behaviour, along with mundanities, and makes them all part of a tapestry of life.

The book’s recurring themes tangle through all of the sections, even though it has been given a somewhat arbitrary four-part structure (Wood – Earth – Water – Rock). Interludes between these major parts transcribe Myers’s field notes, which are more like impromptu poems that he wrote in a notebook kept in his coat pocket. The artistry of these snippets of poetry is incredible given that they were written in situ, and their alliteration bleeds into his prose as well. My favourite of the poems was “On Lighting the First Fire”:

Autumn burns

the sky

the woods

the valley

death is everywhere

but beneath

the golden cloak

the seeds of

a summer’s

dreaming still sing.

The Field Notes sections are illustrated with Myers’s own photographs, which, again, are of enviable quality. I came away from this feeling like Myers could write anything – a thank-you note, a shopping list – and make it read as profound literature. Every sentence is well-crafted and memorable. There is also a wonderful sense of rhythm to his pages, with a pithy sentence appearing every couple of paragraphs to jolt you to attention.

“Writing is a form of alchemy,” Myers declares. “It’s a spell, and the writer is the magician.” I certainly fell under the author’s spell here. While his eyes are open to the many distressing political and environmental changes of the last few years, the ancient perspective of the Rock reminds him that, though humans are ultimately insignificant and individual lives are short, we can still rejoice in our experiences of the world’s beauty while we’re here.

From the publisher:

“Benjamin Myers was born in Durham in 1976. He is a prize-winning author, journalist and poet. His recent novels are each set in a different county of northern England, and are heavily inspired by rural landscapes, mythology, marginalised characters, morality, class, nature, dialect and post-industrialisation. They include The Gallows Pole, winner of the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction, and recipient of the Roger Deakin Award; Turning Blue, 2016; Beastings, 2014 (Portico Prize for Literature & Northern Writers’ Award winner), Pig Iron, 2012 (Gordon Burn Prize winner & Guardian Not the Booker Prize runner-up); and Richard, a Sunday Times Book of the Year 2010. Bloomsbury will publish his new novel, The Offing, in August 2019.

As a journalist, he has written widely about music, arts and nature. He lives in the Upper Calder Valley, West Yorkshire, the inspiration for Under the Rock.”

Blog Tour Review: The Point of Poetry by Joe Nutt

Lots of adults are afraid of poetry, Joe Nutt believes. As a Midlands lad he loved going to the public library and had a magical first encounter with poetry at secondary school – the last time many people will ever read it. A former English teacher and Times Educational Supplement columnist who has written books about Shakespeare, Donne and Milton, he also spent many years in the business world, where he sensed apprehension and even hostility towards poetry. This book is meant as a gentle introduction, or reintroduction, to the joys of reading a poem for yourself.

The 22 chapters each focus on a particular poem, ranging in period and style from the stately metaphysical verse of Andrew Marvell to the rapid-fire performance rhythms of Hollie McNish. The pattern in these essays is to provide background on the poet and his or her milieu or style before moving into more explicit interpretation of the poem’s themes and techniques; the poem is then generally printed at the end of the chapter.*

I most appreciated the essays on poems I already knew and loved but gained extra insight into (“Blackberry-Picking” by Seamus Heaney and “The Darkling Thrush” by Thomas Hardy) or had never read before, even if I knew other things by the same poets (“The Bistro Styx” by Rita Dove and “The Sea and the Skylark” by Gerard Manley Hopkins). The Dove poem echoes the Demeter and Persephone myth as it describes a meeting between a mother and daughter in a Paris café. The mother worries she’s lost her daughter to Paris – and, what’s worse, to a kitschy gift shop and an artist for whom she works as a model. Meanwhile, Heaney, Hardy and Hopkins all reflect – in their various, subtle ways – on environmental and societal collapse and ask what hope we might find in the midst of despair.

Joe Nutt

Other themes that come through in the chosen poems include Englishness and countryside knowledge (E. Nesbit and Edward Thomas), love, war and death. Nutt points out the things to look out for, such as doubling of words or sounds, punctuation, and line length. His commentary is especially useful in the chapters on Donne, Wordsworth and Hopkins. In other chapters, though, he can get sidetracked by personal anecdotes or hang-ups like people not knowing the difference between rifles and shotguns (his main reason for objecting to Vicki Feaver’s “The Gun,” to which he devotes a whole chapter) or Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize. These felt like unnecessary asides and detracted from the central goal of celebrating poetry. One can praise the good without denigrating what one thinks bad, yes?

*Except for a few confusing cases where it’s not. Where’s Ted Hughes’s “Tractor”? If reproduction rights couldn’t be obtained, a different poem should have been chosen. Why does a chapter on Keats’s “The Eve of St. Agnes” quote just a few fragments from it in the text but then end with a passage from Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis (ditto with the excerpt from Donne that ends the chapter on Milton)? The particular Carol Ann Duffy and Robert Browning poems Nutt has chosen are TL; DR, while he errs to the other extreme by not quoting enough from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Paradise Lost, perhaps assuming too much audience familiarity. (I’ve never read either!)

*Except for a few confusing cases where it’s not. Where’s Ted Hughes’s “Tractor”? If reproduction rights couldn’t be obtained, a different poem should have been chosen. Why does a chapter on Keats’s “The Eve of St. Agnes” quote just a few fragments from it in the text but then end with a passage from Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis (ditto with the excerpt from Donne that ends the chapter on Milton)? The particular Carol Ann Duffy and Robert Browning poems Nutt has chosen are TL; DR, while he errs to the other extreme by not quoting enough from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Paradise Lost, perhaps assuming too much audience familiarity. (I’ve never read either!)

So, overall, a bit of a mixed bag: probably better suited to those less familiar with poetry; and, oddly, often more successful for me in its generalizations than in its particulars:

if you once perceive that poetry operates on the edges of man’s knowledge and experience, that it represents in art a profoundly sincere attempt by individuals to grapple with the inexorable conditions of human life, then you are well on the way to becoming not just a reader of it but a fan.

The poet’s skill is in making us look at the world anew, through different, less tainted lenses.

A poem, however unique and strange, however pure and white the page it sits on, doesn’t enter your life unaccompanied. It comes surrounded by literary echoes and memories, loaded with the past. That’s why you get better at understanding [poems], why you enjoy them more, the more you read.

Poetry is so often parsimonious. It makes us work for our supper.

Rossetti deliberately avoids certainty throughout. I enjoy that in any poem. It makes you think.

There is really only one response to great poetry: an unqualified, appreciative ‘yes’.

Related reading:

- The Hatred of Poetry by Ben Lerner

- 52 Ways of Looking at a Poem by Ruth Padel

- The Poem and the Journey and 60 Poems to Read Along the Way by Ruth Padel

- The Poetry Pharmacy by William Sieghart

- Why Poetry by Matthew Zapruder

(I have read and can recommend all of these. Padel’s explication of poetry is top-notch.)

The Point of Poetry was published by Unbound on March 21st (World Poetry Day). My thanks to the publisher for a free copy for review.

Dylan Thomas Prize Blog Tour: Eye Level by Jenny Xie

The Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize recognizes the best published work in the English language written by an author aged 39 or under. All literary genres are eligible, so short stories and poetry sit alongside novels on this year’s longlist of 12 titles:

- Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Friday Black

- Michael Donkor, Hold

- Clare Fisher, How the Light Gets In

- Zoe Gilbert, Folk

- Emma Glass, Peach

- Guy Gunaratne, In Our Mad and Furious City

- Louisa Hall, Trinity

- Sarah Perry, Melmoth

- Sally Rooney, Normal People

- Richard Scott, Soho

- Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, House of Stone

- Jenny Xie, Eye Level

For this stop on the official blog tour, I’m featuring the debut poetry collection Eye Level by Jenny Xie (winner of the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets), which was published by Graywolf Press in 2018 and was a National Book Award finalist in the USA last year. Xie, who was born in Hefei, China and grew up in New Jersey, now teaches at New York University. Her poems focus on the sense of displacement that goes hand in hand with immigration or just everyday travel, and on familial and evolutionary inheritance.

The opening sequence of poems is set in Vietnam, Cambodia and Corfu, with heat and rain as common experiences that also enter into the imagery: “See, counting’s hard in half-sleep, and the rain pulls a sheet // over the sugar palms and their untroubled leaves” and “The riled heat reaches the river shoal before it reaches the dark.” The tragic and the trivial get mixed up in ordinary sightseeing:

The tourists curate vacation stories,

days summed up in a few lines.

Killing fields tour, Sambo the elephant

in clotted street traffic,

dusky-complexioned children hesitant in their approach.

Seeing and being seen are a primary concern, with the “eye” of the title deliberately echoing the “I” that narrates most of the poems. I actually wondered if there was a bit too much first person in the book, which always complicates the question of whether the narrator equals the poet. One tends to assume that the story of a father going to study in the USA and the wife following, giving up her work as a doctor for a dining hall job, is autobiographical. The same goes for the experiences in “Naturalization” and “Exile.”

The metaphors Xie uses for places are particularly striking, often likening a city/country to a garment or a person’s appearance: “Seeing the collars of this city open / I wish for higher meaning and its histrionics to cease,” “The new country is ill fitting, lined / with cheap polyester, soiled at the sleeves,” and “Here’s to this new country: / bald and without center.”

The poet contemplates what she has absorbed from her family line and upbringing, and remembers the sting of feeling left behind when a romance ends:

I thought I owned my worries, but here I was only pulled along by the needle

of genetics, by my mother’s tendency to pry at openings in her life.

Love’s laws are simple. The leaving take the lead.

The left-for takes a knife to the knots of narrative.

Those last two lines are a good example of the collection’s reliance on alliteration, which, along with repetition, is used much more often than end rhymes and internal or slant rhymes. Speaking of which, this was my favorite pair of lines:

Slant rhyme of current thinking

and past thinking.

Meanwhile, my single favorite poem was “Hardwired,” about the tendency to dwell on the negative:

Though I didn’t always connect with Xie’s style – it can be slightly detached and formal in a way that is almost at odds with the fairly personal subject matter, and there were some pronouncements that seemed to me not as profound as they intended to be (it may well be that her work would be best read aloud) – there were occasional lines and images that pulled me up short and made me think, Yes, she gets it. What it’s like to be from one place but live in another; what it’s like to be fond but also fearful of the ways in which you resemble your parents. I expect this to be a strong contender for the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist, which will be announced on April 2nd. The winner is then announced on May 16th.

My thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review.

Wellcome Book Prize 10th Anniversary Blog Tour: Teach Us to Sit Still by Tim Parks (2010)

“Launched in 2009, the Wellcome Book Prize, worth £30,000, celebrates the best new books that engage with an aspect of medicine, health or illness, showcasing the breadth and depth of our encounters with medicine through exceptional works of fiction and non-fiction.” I was delighted to be asked to participate in the official Wellcome Book Prize 10th anniversary blog tour. For this stop on the tour I’m highlighting a shortlisted title from 2010, a very strong year. The winning book, Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, along with Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Emperor of All Maladies, turned me on to health-themed reading and remains one of my most memorable reads of the past decade.

Teach Us to Sit Still: A Sceptic’s Search for Health and Healing by Tim Parks

Tim Parks, an Englishman, has lived and worked in Italy for over 30 years. He teaches translation at the university in Milan, and is also a novelist and a frequent newspaper columnist on literary topics. Starting in his forties, Parks was plagued by urinary problems and abdominal pain. Each night he had to get up five or six times to urinate, and when he didn’t have fiery pangs shooting through his pelvic area he had a dull ache. Doctors assessed his prostate and bladder in tests that seemed more like torture sessions, but ultimately found nothing wrong. While he was relieved that his worst fears of cancer were allayed, he was left with a dilemma: constant, unexplained discomfort and no medical strategy for treating it.

Tim Parks, an Englishman, has lived and worked in Italy for over 30 years. He teaches translation at the university in Milan, and is also a novelist and a frequent newspaper columnist on literary topics. Starting in his forties, Parks was plagued by urinary problems and abdominal pain. Each night he had to get up five or six times to urinate, and when he didn’t have fiery pangs shooting through his pelvic area he had a dull ache. Doctors assessed his prostate and bladder in tests that seemed more like torture sessions, but ultimately found nothing wrong. While he was relieved that his worst fears of cancer were allayed, he was left with a dilemma: constant, unexplained discomfort and no medical strategy for treating it.

When conventional medicine failed him, Parks asked himself probing questions: Had he in some way brought this pain on himself through his restless, uptight and pessimistic ways? Had he ever made peace with his minister father’s evangelical Christianity after leaving it for a life based on reason? Was his obsession with transmuting experience into words keeping him from living authentically? During a translation conference in Delhi, he consulted an ayurvedic doctor on a whim and heard words that haunted him: “This is a problem you will never get over, Mr Parks, until you confront the profound contradiction in your character.”

The good news is: some things helped. One was the book A Headache in the Pelvis, which teaches a paradoxical relaxation technique that Parks used for up to an hour a day, lying on a yoga mat in his study. Another was exercise, especially running and kayaking – a way of challenging himself and seeking thrills in a controlled manner. He also started shiatsu therapy. And finally, Vipassana meditation retreats helped him shift his focus off the mind’s experience of pain and onto bodily wholeness. Vipassana is all about “seeing things as they really are,” so the retreats were for him a “showdown with this tangled self” and a chance to face the inevitability of death. Considering he couldn’t take notes at the time, I was impressed by the level of detail with which Parks describes his breakthroughs during meditation.

Though I was uneasy reading about a middle-aged man’s plumbing issues and didn’t always follow the author on his digressions into literary history (Coleridge et al.), I found this to be an absorbing and surprising quest narrative. If not with the particulars, I could sympathize with the broader strokes of Parks’s self-interrogation. He wonders whether sitting at a desk, tense and with poor posture, and wandering around with eyes on the ground and mind on knots of words for years contributed to his medical crisis. Borrowing the title phrase from T.S. Eliot, he’s charted an unlikely journey towards mindfulness in a thorough, bracingly honest, and diverting book that won’t put off those suspicious of New Age woo-woo.

My rating:

With thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review.

Wellcome Book Prize 2010

Winner: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

Shortlist: Angel of Death by Gareth Williams; Grace Williams Says It Loud by Emma Henderson; So Much for That by Lionel Shriver; Medic by John Nicols and Tony Rennell; Teach Us to Sit Still by Tim Parks

Judges: Comedy writer and television presenter Clive Anderson (chair); novelist and academic Maggie Gee; academic and writer Michael Neve; television presenter and author Alice Roberts; academic and writer A.C. Grayling

The 2019 Wellcome Book Prize longlist will be announced in February. I’m already looking forward to it, of course, and I’m planning to run a shadow panel once again.

Elif Shafak, award-winning author, is the chair of this year’s judges and is joined on the panel by Kevin Fong, consultant anaesthetist at University College London Hospitals; Viv Groskop, writer, broadcaster and stand-up comedian; Jon Day, writer, critic, and academic; and Rick Edwards, broadcaster and author.

See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon as part of the Wellcome Book Prize 10th anniversary blog tour.

Blog Tour: Literary Landscapes, edited by John Sutherland

The sense of place can be a major factor in a book’s success – did you know there is a whole literary prize devoted to just this? (The Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize, “for a distinguished work of fiction, non-fiction or poetry, evoking the spirit of a place.”) No matter when or where a story is set, an author can bring it to life through authentic details that appeal to all the senses, making you feel like you’re on Prince Edward Island or in the Gaudarrama Mountains even if you’ve never visited Atlantic Canada or central Spain. The 75 essays of Literary Landscapes, a follow-up volume to 2016’s celebrated Literary Wonderlands, illuminate the real-life settings of fiction from Jane Austen’s time to today. Maps, author and cover images, period and modern photographs, and other full-color illustrations abound.

The sense of place can be a major factor in a book’s success – did you know there is a whole literary prize devoted to just this? (The Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize, “for a distinguished work of fiction, non-fiction or poetry, evoking the spirit of a place.”) No matter when or where a story is set, an author can bring it to life through authentic details that appeal to all the senses, making you feel like you’re on Prince Edward Island or in the Gaudarrama Mountains even if you’ve never visited Atlantic Canada or central Spain. The 75 essays of Literary Landscapes, a follow-up volume to 2016’s celebrated Literary Wonderlands, illuminate the real-life settings of fiction from Jane Austen’s time to today. Maps, author and cover images, period and modern photographs, and other full-color illustrations abound.

Each essay serves as a compact introduction to a literary work, incorporating biographical information about the author, useful background and context on the book’s publication, and observations on the geographical location as it is presented in the story – often through a set of direct quotations. (Because each work is considered as a whole, you may come across spoilers, so keep that in mind before you set out to read an essay about a classic you haven’t read but still intend to.) The authors profiled range from Mark Twain to Yukio Mishima and from Willa Cather to Elena Ferrante. A few of the world’s great cities appear in multiple essays, though New York City as variously depicted by Edith Wharton, Jay McInerney and Francis Spufford is so different as to be almost unrecognizable as the same place.

One of my favorite pieces is on Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. “Dickens was not interested in writing a literary tourist’s guide,” it explains; “He was using the city as a metaphor for how the human condition could, unattended, go wrong.” I also particularly enjoyed those on Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped. The fact that I used to live in Woking gave me a special appreciation for the essay on H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, “a novel that takes the known landscape and, brilliantly, estranges it.” The two novels I’ve been most inspired to read are Thomas Wharton’s Icefields (1995; set in Jasper, Alberta) and Kate Grenville’s The Secret River (2005; set in New South Wales).

The essays vary subtly in terms of length and depth, with some focusing on plot and themes and others thinking more about the author’s experiences and geographical referents. They were contributed by academics, writers and critics, some of whom were familiar names for me – including Nicholas Lezard, Robert Macfarlane, Laura Miller, Tim Parks and Adam Roberts. My main gripe about the book would be that the individual essays have no bylines, so to find out who wrote a certain one you have to flick to the back and skim through all the contributor biographies until you spot the book in question. There are also a few more typos than I tend to expect from a finished book from a traditional press (e.g. “Lady Deadlock” in the Bleak House essay!). Still, it is a beautifully produced, richly informative tome that should make it onto many a Christmas wish list this year; it would make an especially suitable gift for a young person heading off to study English at university. It’s one to have for reference and dip into when you want to be inspired to discover a new place via an armchair visit.

Literary Landscapes will be published by Modern Books on Thursday, October 25th. My thanks to Alison Menzies for arranging my free copy for review.

Blog Tour Review: The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon

The Incendiaries is a sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Will Kendall left his California Bible college when he lost his faith. Soon after transferring to Edwards in upstate New York, he falls for Phoebe Lin at a party. Although he’s working in a restaurant to pay his way, he hides his working-class background to fit in with Phoebe and her glitzy, careless friends. Phoebe is a failed piano prodigy who can’t forgive herself: her mother died in a car Phoebe was driving. John Leal, a half-Korean alumnus, worked with refugees in China and was imprisoned in North Korea. Now he’s started a vaguely Christian movement called Jejah (Korean for “disciple”) that involves forced baptisms, intense confessions and self-flagellation. It’s no coincidence his last name rhymes with zeal.

The Incendiaries is a sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Will Kendall left his California Bible college when he lost his faith. Soon after transferring to Edwards in upstate New York, he falls for Phoebe Lin at a party. Although he’s working in a restaurant to pay his way, he hides his working-class background to fit in with Phoebe and her glitzy, careless friends. Phoebe is a failed piano prodigy who can’t forgive herself: her mother died in a car Phoebe was driving. John Leal, a half-Korean alumnus, worked with refugees in China and was imprisoned in North Korea. Now he’s started a vaguely Christian movement called Jejah (Korean for “disciple”) that involves forced baptisms, intense confessions and self-flagellation. It’s no coincidence his last name rhymes with zeal.

Much of the book is filtered through Will’s perspective; even sections headed “Phoebe” and “John Leal” most often contain his second-hand recounting of Phoebe’s words, or his imagined rendering of Leal’s thoughts – bizarre and fervent. Only in a few spots is it clear that the “I” speaking is actually Phoebe. This plus a lack of speech marks makes for a somewhat disorienting reading experience, but that is very much the point. Will and Phoebe’s voices and personalities start to merge until you have to shake your head for some clarity. The irony that emerges is that Phoebe is taking the opposite route to Will’s: she is drifting from faithless apathy into radical religion, drawn in by Jejah’s promise of atonement.

As in Celeste Ng’s novels, we know from the very start the climactic event that powers the whole book: the members of Jejah set off a series of bombs at abortion clinics, killing five. The mystery, then, is not so much what happened but why. In particular, we’re left to question how Phoebe could be transformed so quickly from a vapid party girl to a religious extremist willing to suffer for her beliefs.

Kwon spent 10 years writing this book, and that time and diligence come through in how carefully honed the prose is: such precise images; not a single excess word. I can see how some might find the style frustratingly oblique, but for me it was razor sharp, and the compelling religious theme was right up my street. It’s a troubling book, one that keeps tugging at your elbow. Recommended to readers of Sweetbitter and Shelter.

Favorite lines:

“This has been the cardinal fiction of my life, its ruling principle: if I work hard enough, I’ll get what I want.”

“People with no experience of God tend to think that leaving the faith would be a liberation, a flight from guilt, rules, but what I couldn’t forget was the joy I’d known, loving Him.”

My rating:

The Incendiaries will be published by Virago Press on September 6th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Note: An excerpt from The Incendiaries appeared in The Best Small Fictions 2016 (ed. Stuart Dybek), which I reviewed for Small Press Book Review. I was interested to look back and see that, at that point, her work in progress was entitled Heroics.

I was delighted to be invited to participate in the blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews are appearing today.

Blog Tour: Extract from The Power of Dog by Andrew G. Marshall

Last April I participated in the blog tour for Andrew G. Marshall’s previous book, My Mourning Year, a memoir about the death of his partner Thom and his journey through grief.

Last April I participated in the blog tour for Andrew G. Marshall’s previous book, My Mourning Year, a memoir about the death of his partner Thom and his journey through grief.

The Power of Dog is like a sequel; it tells what happened when Andrew acquired a collie cross puppy named Flash.

Alas, a copy didn’t arrive in time for me to read it before I left for America, but to open up the blog tour today I have an extract for you, and I look forward to reading the book when I get back.

Prologue

What I wanted most and what frightened me most, when I was a child, turned out to be the same thing. Every year as I blew out my birthday cake candles, I’d wish for a puppy ‒ with my eyes tightly closed to maximise the magic. But while my daydreams were full of adoring Labradors fetching sticks, my nightmares were stalked by their distant relatives: wolves.

My parents belonged to the ‘comfortably off’ middle classes and were only too happy to pay for tennis lessons, new bikes and summer camp – indeed they were particularly keen to send me to these. My birthday cake was always home baked, a fruit cake decorated with teddy bears sitting in a spiky snow scene. Despite the growing number of candles and my entreaties, the gods of birthday wishes were unmoved. Although my mother agreed first to guinea pigs and later mice, she remained firm about getting a dog: ‘I’ll be the one who ends up walking it.’

I can pinpoint the exact moment the nightmares started. Our next-door neighbours, whom I’d christened H’auntie and H’uncle, had retired to Bournemouth and one summer we stayed overnight at their house. I must have been four or five and already possessed a vivid imagination. In the middle of the night, I had to tiptoe across an unfamiliar landing to the lavatory ‒ never toilet because my mother considered the term vulgar. Returning, I closed the bedroom door as quietly as possible and revealed a large hairy wolf ready to pounce. I can’t remember if I screamed or whether anybody came. Maybe my mother pointed out that the wolf was really a man’s woollen winter dressing gown hanging on a hook; all of those details have been forgotten but I can still remember the nightmares.

Back home in Northampton, I slept in a tall wooden bed which had originally belonged to my father. The mattress and the springs were so old that they had sunk to form a hollow which fitted exactly around my small body. I felt safe nestling between the two hills on either side. However, the old-fashioned design left a large amount of space under the bed. By day, this space housed a box of favourite toys, but at night I never had the nerve to lift the white candlewick counterpane. I instinctively knew the wolves had set up camp there. The rules of engagement were simple: I was safe in bed, but they could pounce and catch me if I didn’t run fast enough back from the loo ‒ an acceptable abbreviation. On particularly dark nights, the wolves would emerge from their lair and dance round the room with their teeth glinting in the moonlight. I’d scream out and Mummy would come and reassure me:

‘The wolves will not get you.’

She would lift the counterpane and show me.

‘There’s nothing there.’

It was easy for her to say – the wolves would disappear as soon as she’d open my bedroom door. But after she’d told me to ‘sleep tight’ and gone back to bed, they would rematerialise, slink back into the lair and an uneasy truce would be established.

Wolves did not have a monopoly on my fears. For a while in the sixties a ‘cop killer’ called Harry Roberts evaded the police by haunting my nightmares. If there was a strange-looking man drinking alone at the rugby club bar ‒ where my father was treasurer ‒ I would sidle up to one of my parents and whisper: ‘THERE’S HARRY ROBERTS.’ It must have been embarrassing for my parents, but in defence of my seven-year-old self, the rugby club did attract an odd crowd.

Fortunately, my fear of Harry Roberts was easy to cure. One night in 1966, I was allowed to stay up late to watch his capture on the news. I can still picture the small makeshift camp in the woods ‒ the blanket strung between three trees and the discarded tin cans ‒ but not where (except it was many miles from my home). I slept soundly that night.

Flushed by her success with Harry Roberts, my mother took me to London Zoo. I was softened up with lions, monkeys and possibly even a ride on an elephant. Next, she casually mentioned that they had wolves too. I can’t remember what I was wearing but I can picture myself in an anorak so large it came down past my knees ‒ ‘you’ll grow into it’ – being taken to an enclosure hidden in some back alley of the Zoo. Did I actually look at the wolves? Perhaps I refused. Perhaps they were asleep in their den. Whatever happened next, the pack under my bed would not be exorcised so easily.

At that age it was impossible to believe I would ever reach ten; but I did. I even turned eighteen and left home for university where I studied Politics and Sociology. After graduating, I got a job first at BRMB Radio in Birmingham (in the newsroom) and then Essex Radio in Southend (as a presenter and producer) and Radio Mercury in Crawley (where I rose to become Deputy Programme Controller). My nightmares about wolves had long since ended, but if they appeared on TV they would still make me feel uneasy and I would switch channels. I still wanted a dog, but I was far too practical. I had a career to pursue. Who would walk the dog? Would it be fair to leave it alone while I worked? I couldn’t be tied down by such responsibilities.

At thirty, I fell in love with Thom and we talked about getting a dog together. However, for the first four and a half years, he lived in Germany and I lived in Hurstpierpoint (a small Sussex village). In the spring of 1995, Thom finally moved over to England with plans to set up an interior design company. However, six months later, he fell ill. All our plans for dog-owning were put on hold, while we concentrated on getting him better. He spent months in hospital first in England and then in Germany and I spent a lot of time flying backwards and forwards between the two countries. I loved Thom with a passion that sometimes terrified me, so when he died, on 9 March 1997, I was completely inconsolable.

I moved into the office he’d created in our spare room, but I couldn’t stop the computer from still sending faxes from Andrew Marshall and Thom Hartwig. As far as Microsoft Word was concerned, he was immortal. I tried various strategies to cope with my bereavement but three different counsellors did not shift it. Two short-term relationships made me feel worse not better. I had just turned forty. My regular sources of income – being Agony Uncle for Live TV and writing a column for the Independent newspaper – were both terminated. My grief was further isolating me and many of Thom’s and my couple friendships had just withered away.

Approaching the Millennium, something had to change, but what?

The Power of Dog will be released by RedDoor Publishing on Thursday, July 12th. My thanks to the publisher for a review copy.

Blog Tour: Extract from Song by Michelle Jana Chan

Song escapes the poverty and natural disasters of his hometown in China by sailing to Guiana. The village medicine man describes Guiana as a kind of paradise, and tells him he can earn free passage if he presents himself to the Englishmen in Guangzhou. What he doesn’t realize is that he will effectively be an indentured servant, working in the sugarcane fields for years just to pay for the voyage. From Singapore to India to Guiana, it’s a long and fraught journey, and though his new home does dazzle with its colors and wildlife, it’s not the idyll he expected. Still, Song is determined to make something of himself. “He would yet live a life that was a story worth telling.”

Song escapes the poverty and natural disasters of his hometown in China by sailing to Guiana. The village medicine man describes Guiana as a kind of paradise, and tells him he can earn free passage if he presents himself to the Englishmen in Guangzhou. What he doesn’t realize is that he will effectively be an indentured servant, working in the sugarcane fields for years just to pay for the voyage. From Singapore to India to Guiana, it’s a long and fraught journey, and though his new home does dazzle with its colors and wildlife, it’s not the idyll he expected. Still, Song is determined to make something of himself. “He would yet live a life that was a story worth telling.”

I have an extract from Chapter 1, about the flooding in China, to whet your appetite:

Lishui Village, China, 1878

At first they were glad the rains came early. They had already finished their planting and the seedlings were beginning to push through. The men and women of Lishui straightened their backs, buckled from years of labouring, led the buffalo away and waited for the fields to turn green. With such early rains there might be three rice harvests if the weather continued to be clement. But they quickly lost hope of that. The sun did not emerge to bronze the crop. Instead the clouds hung heavy. More rain beat down upon an already sodden earth and lakes were born where even the old people said they could not remember seeing standing water.

The Li rose higher and higher. Every morning the men of the village walked to the river to watch the water lap at its banks like flames. Sometimes they stood there for hours, their faces as grey as the flat slate light. Still the rain fell, yet no one cared about their clothes becoming wet or the nagging coughs the chill brought on. Occasionally a man lifted his arm to wipe his face. But mostly they stood still like figures in a painting, staring upstream, watching the water barrel down, bulging under its own mass.

Before the end of the week the Li had spilled over its banks. A few days later the water had covered the footpaths and cart tracks, spreading like a tide across the land and sweeping away all the fine shoots of newly planted rice. Further upstream the river broke up carts, bamboo bridges and outbuildings; it knocked over vats of clean water and seeped beneath the doors of homes. Carried on its swirling currents were splintered planks of wood, rotting food, and shreds of sacking and rattan.

Song awoke to feel the straw mat wet beneath him. He reached out his hand. The water was gently rising and ebbing as if it was breathing. His brother Xiao Bo was crying in his sleep. The little boy had rolled off his mat and was lying curled up in the water. He was hugging his knees as if to stop himself from floating away.

Song’s father was not home yet. He and the other men had been working through the night trying to raise walls of mud and rein back the river’s strength. But the earthen barriers washed away even as they built them; they could only watch, hunched over their shovels.

The men did not return that day. As the hours passed the women grew anxious. They stopped by each other’s homes, asking for news, but nobody had anything to say. Song’s mother Zhang Je was short with the children. The little ones whimpered, sensing something was wrong.

Song huddled low with his sisters and brothers around the smoking fire which sizzled and spat but gave off no heat. They had wedged among the firewood an iron bowl but the rice inside was not warming. That was all they had left to eat now. Xiao Wan curled up closer to Song. His little brother followed him everywhere nowadays. His sisters Xiao Mei and San San sat opposite him, adding wet wood to the fire and poking at the ash with a stick. His mother stood in the doorway, the silhouette of Xiao Bo strapped to her back and her large rounded stomach tight with child.

The children dipped their hands into the bowl, squeezing grains of rice together, careful not to take more than their share. Song was trying to feed Xiao Wan but he was too weak even to swallow. The little boy closed his eyes and rested his head in Song’s lap, wheezing with each breath. Their mother continued to look out towards the fields, waiting, with Xiao Bo’s head slumped unnaturally to the side as he slept.

‘I don’t think they’re coming back.’

Song could barely hear what his mother was saying.

‘They’re too late,’ she muttered.

Song wasn’t sure if she was talking to him. ‘Mama?’

Her voice was more brisk. ‘They’re not coming back, I said.’

Like so many children on both sides of the Atlantic, I grew up with Roald Dahl’s classic tales: James and the Giant Peach, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and Matilda. I was aware that he had published work for adults, too, but hadn’t experienced any of it until I was asked to join this blog tour in advance of Roald Dahl Day on September 13th.

Like so many children on both sides of the Atlantic, I grew up with Roald Dahl’s classic tales: James and the Giant Peach, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and Matilda. I was aware that he had published work for adults, too, but hadn’t experienced any of it until I was asked to join this blog tour in advance of Roald Dahl Day on September 13th.

I also dipped into Trickery: Tales of Deceit and Cunning and particularly liked “The Wish,” in which a boy imagines a carpet is a snakepit and then falls into it, and “Princess Mammalia,” a Princess Bride-style black comedy about a royal who decides to wrest power from her father but gets her mischief turned right back on her. I’ll also pick up Fear, Dahl’s curated set of ghost stories by other authors, during October for the R.I.P. challenge.

I also dipped into Trickery: Tales of Deceit and Cunning and particularly liked “The Wish,” in which a boy imagines a carpet is a snakepit and then falls into it, and “Princess Mammalia,” a Princess Bride-style black comedy about a royal who decides to wrest power from her father but gets her mischief turned right back on her. I’ll also pick up Fear, Dahl’s curated set of ghost stories by other authors, during October for the R.I.P. challenge.