Poetry Month Reviews & Interview: Amy Gerstler, Richard Scott, Etc.

April is National Poetry Month in the USA, and I was delighted to have several of my reviews plus an interview featured in a special poetry issue of Shelf Awareness on Friday. I’ve also recently read Richard Scott’s second collection.

Wrong Winds by Ahmad Almallah

Palestinian poet Ahmad Almallah’s razor-sharp third collection bears witness to the devastation of Gaza.

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Tonally, anger and grief alternate, while alliteration and slant rhymes (sweat/sweet) create entrancing rhythms. In “Before Gaza, a Fall” and “My Tongue Is Tied Up Today,” staccato phrasing and spaced-out stanzas leave room for the unspeakable. The pièce de résistance is “A Holy Land, Wasted” (co-written with Huda Fakhreddine), which situates T.S. Eliot’s existential ruin in Palestine. Almallah contrasts Gaza then and now via childhood memories and adult experiences at checkpoints. His pastiche of “The Waste Land” starts off funny (“April is not that bad actually”) but quickly darkens, scorning those who turn away from tragedy: “It’s not good/ for your nerves to watch/ all that news, the sights/ of dead children.” The wordplay dazzles again here: “to motes the world crumbles, shattered/ like these useless mots.”

For Almallah, who now lives in Philadelphia, Gaza is elusive, enduringly potent—and mourned. Sometimes earnest, sometimes jaded, Wrong Winds is a remarkable memorial. ![]()

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. “As Winter Sets In” delivers “every day/ a new face you can’t renounce or forsake.” “When I was a bird,” with its interspecies metamorphoses, introduces a more fantastical concept: “I once observed a scurry of squirrels,/ concealed in a hollow tree, wearing seventeenth/ century clothes. Alas, no one believes me.” Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen.

The collection contains five thematic slices. Part I spotlights women behaving badly (such as “Marigold,” about a wild friend; and “Mae West Sonnet,” in an hourglass shape); Part II focuses on music and sound. The third section veers from the inherited grief of “Schmaltz Alert” to the miniplay “Siren Island,” a tragicomic Shakespearean pastiche. Part IV spins elegies for lives and works cut short. The final subset includes a tongue-in-cheek account of pandemic lockdown activities (“The Cure”) and wry advice for coping (“Wound Care Instructions”).

Monologues and sonnets recur—the title’s “form” refers to poetic structures as much as to personal identity. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance. In the closing poem, “Night Herons,” nature puts life into perspective: “the whir of wings/ real or imagined/ blurs trivial things.”

This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques.

I also had the chance to interview Amy Gerstler, whose work was new to me. (I’ll certainly be reading more!) We chatted about animals, poetic forms and tone, Covid, the Los Angeles fires, and women behaving ‘badly’. ![]()

Little Mercy by Robin Walter

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

Many of Walter’s poems are as economical as haiku. “Lilies” entrances with its brief lines, alliteration, and sibilance: “Come/ dark, white/ petals// pull/close// —small fists// of night—.” A poem’s title often leads directly into the text: “Here” continues “the body, yes,/ sometimes// a river—little/ mercy.” Vocabulary and imagery reverberate, as the blessings of morning sunshine and a snow-covered meadow salve an unquiet soul (“how often, really, I want/ to end my life”).

Frequent dashes suggest affinity with Emily Dickinson, whose trademark themes of loss, nature, and loneliness are ubiquitous here, too. Vistas of the American West are a backdrop for pronghorn antelope, timothy grass, and especially the wrens nesting in Walter’s porch. Animals are also seen in peril sometimes: the family dog her father kicked in anger or a roadkilled fox she encounters. Despite the occasional fragility of the natural world, the speaker is “held by” it and granted “kinship” with its creatures. (How appropriate, she writes, that her mother named her for a bird.)

The collection skillfully illustrates how language arises from nature (“while picking raspberries/ yesterday I wanted to hold in my head// the delicious names of the things I saw/ so as to fold them into a poem later”—a lovely internal rhyme) and becomes a memorial: “Here, on earth,/ we honor our dead// by holding their names/ gentle in our hollow mouths—.”

This poised, place-saturated collection illuminates life’s little mercies. ![]()

The three reviews above are posted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

That Broke into Shining Crystals by Richard Scott

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

It also mirrors his debut in that the book is in several discrete sections – like movements of a musical composition – and there are extended allusions to particular poets (there, Paul Verlaine and Walt Whitman; here, Andrew Marvell and Arthur Rimbaud). But there is one overall theme, and it’s a tough one: Scott’s boyhood grooming and molestation by a male adult, and how the trauma continues to affect him.

Part I contains 21 “Still Life” poems based on particular paintings, mostly by Dutch or French artists (see the Notes at the end for details). I preferred to read the poems blind so that I didn’t have the visual inspiration in my head. The imagery is startlingly erotic: the collection opens with “Like a foreskin being pulled back, the damask / reveals – pelvic bowl of pink-fringed shadow” (“Still Life with Rose”) and “Still Life with Bananas” starts “curved like dicks they sit – cosy in wicker – an orgy / of total yellowness – all plenty and arching – beyond / erect – a basketful of morning sex and sugar and sunlight”.

“O I should have been the / snail,” the poet laments; “Living phallus that can hide when threatened. But / I’m the oyster. … Cold jelly mess of a / boy shucked wide open.” The still life format allows him to freeze himself at particular moments of abuse or personal growth; “still” can refer to his passivity then as well as to his ongoing struggle with PTSD.

Part II, “Coy,” is what Scott calls a found poem or “vocabularyclept,” rearranging the words from Marvell’s 1681 “To His Coy Mistress” into 21 stanzas. The constraint means the phrases are not always grammatical, and the section as a whole is quite repetitive.

The title of the book (and of its final section) comes from Rimbaud and, according to the Notes, the 22 poems “all speak back to Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations but through the prism of various crystals and semi-precious stones – and their geological and healing properties.” My lack of familiarity with Rimbaud and his circle made me wonder if I was missing something, yet I thrilled to how visual the poems in this section were.

As with the Still Lifes, there’s an elevated vocabulary, forming a rich panoply of plants, creatures, stones, and colours. Alliteration features prominently throughout, as in “Citrine”: “O citrine – patron saint of the molested, sunny eliminator – crown us with your polychromatic glittering and awe-flecks. Offer abundance to those of us quarried. A boy is igneous.”

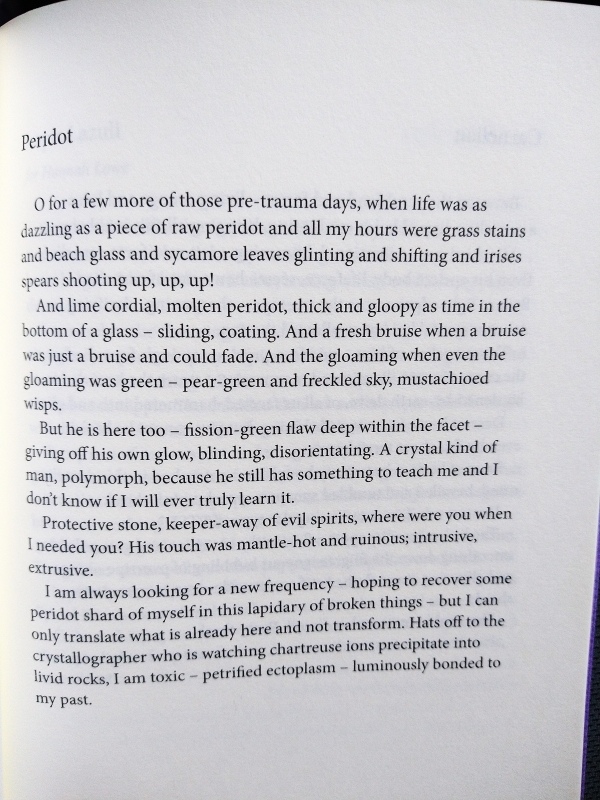

I’ve photographed “Peridot” (which was my mother’s birthstone) as an example of the before-and-after setup, the gorgeous language including alliteration, the rhetorical questioning, and the longing for lost innocence.

It was surprising to me that Scott refers to molestation and trauma so often by name, rather than being more elliptical – as poetry would allow. Though I admire this collection, my warmth towards it ebbed and flowed: I loved the first section; felt alienated by the second; and then found the third rather too much of a good thing. Perhaps encountering Part I or III as a chapbook would have been more effective. As it is, I didn’t feel the sections fully meshed, and the theme loses energy the more obsessively it’s repeated. Nonetheless, I’d recommend it to readers of Mark Doty, Andrew McMillan and Brandon Taylor. ![]()

Published today. With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review. An abridged version of this review first appeared in my Instagram post of 11 April.

Read any good poetry recently?

Interview with Neil Griffiths of Weatherglass Books (#NovNov24)

Back in September, I attended a great “The Future of the Novella” event in London, hosted by Weatherglass. I wrote about it here, and earlier this month I reviewed the first of the two winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, Astraea by Kate Kruimink*. Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths kindly sent review copies of both winning books, and agreed to answer some questions over e-mail.

Back in September, I attended a great “The Future of the Novella” event in London, hosted by Weatherglass. I wrote about it here, and earlier this month I reviewed the first of the two winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, Astraea by Kate Kruimink*. Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths kindly sent review copies of both winning books, and agreed to answer some questions over e-mail.

Samantha Harvey’s 136-page Orbital won the Booker Prize, the film adaptation of Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These is in cinemas: Is the novella having a moment? If so, how do you account for its fresh prominence? Or has it always been a powerful form and we’re realizing it anew?

I do wonder whether Orbital is a novella, by which I mean, number of pages can be deceptive – there are a lot of words per page! I think it probably sneaks in under our Novella Prize max word count: under 40K. Also, I wonder whether Small Things like These would make it over our minimum 20K. I don’t think so. But what I think we can say is that there is something happening around length.

I do wonder whether Orbital is a novella, by which I mean, number of pages can be deceptive – there are a lot of words per page! I think it probably sneaks in under our Novella Prize max word count: under 40K. Also, I wonder whether Small Things like These would make it over our minimum 20K. I don’t think so. But what I think we can say is that there is something happening around length.

My co-founder of Weatherglass, Damian Lanigan, says this: “the novella is the form for our times: befitting our short attention spans, but also with its tight focus, with its singular atmosphere – it’s the ideal form for glimpsing something essential about the world and ourselves in an increasingly chaotic world.”

But then if we look over the history of the prose fiction over the last 200 hundred years, there are so many novellas that have defined an era: Turgenev’s Love, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Carr’s A Month in the Country, Orwell’s Animal Farm, Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Why did Weatherglass choose to focus on short books? Do economic and environmental factors come into it (short books = less paper = lower printing costs as well as fewer trees cut down)?

Economic and environmental factors play a role, but there is also craft. Writers need to ask themselves the question: does this story need to be this length, and the answer is, more often than not: no. I think constraints bring the best out of writers. If a novel comes in at 70K words, our first thought is to cut 10K. (I should say, my last novel, very kindly reviewed by yourself, was a whooping 190K words. It should have been 150K! Since then I’ve written two pieces of fiction, both under 35K.)

Economic and environmental factors play a role, but there is also craft. Writers need to ask themselves the question: does this story need to be this length, and the answer is, more often than not: no. I think constraints bring the best out of writers. If a novel comes in at 70K words, our first thought is to cut 10K. (I should say, my last novel, very kindly reviewed by yourself, was a whooping 190K words. It should have been 150K! Since then I’ve written two pieces of fiction, both under 35K.)

Neil Griffiths

We’ve heard about the bloating of films, that they’re something like 20% longer on average than they were 40 years ago; will books take the opposite trajectory? Can a one-sitting read compete with a film?

I don’t think I’ve ever read even the shortest novella in one sitting. I need time to reflect. I don’t think comparing the two forms is helpful because they require different things of us. Take music: Morton Feldman’s 2nd String Quartet is 5 hours long, without a break. I’d commit to that in the concert hall, but I couldn’t read for 5 hours without a break or sit through a film.

How did you bring Ali Smith on board as the judge for the first two years of the Weatherglass Novella Prize? There was a blind judging process and you ended up with an all-female shortlist in the inaugural year. Do you have a theory as to why?

Ali Smith

Damian kept saying Ali Smith would be the best judge and I kept saying “but how do we get to her?” Then someone told me they had her email address. I didn’t expect to get an answer. A ‘Yes’ came an hour later. She’s been wonderful to work with. And she’s enjoyed it so much she’s agreed to do it ongoingly.

I do think the shortlist question is an important one. Certainly we don’t have to ask ourselves any questions when it’s an all-female short list, but we would if it was all-male. What does that say? I don’t know why the strongest were by women.

Do you have any personal favourite novellas?

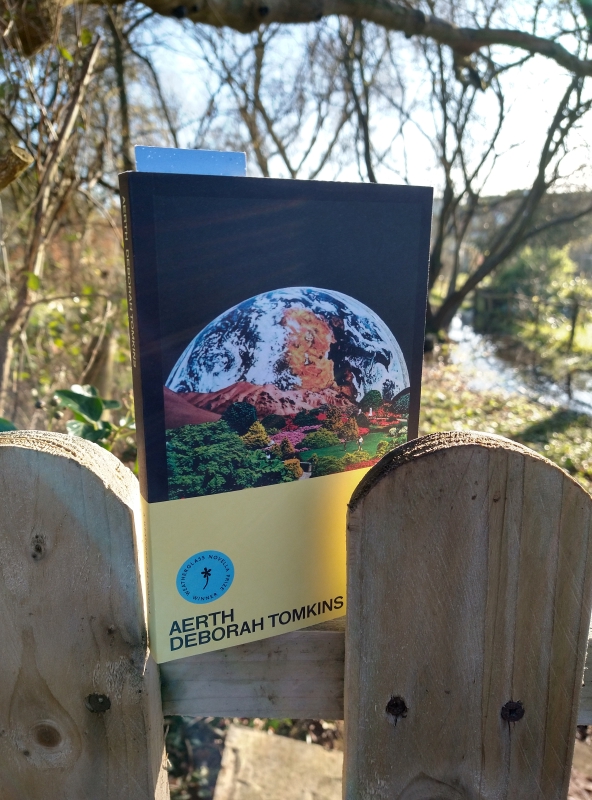

A Month in the Country might be the exemplar of the form for me. But there is a little-read novella by Tolstoy, Hadji Murat, which is also close to perfect. More contemporaneously, Gerald Murnane’s Border Districts. And I’m pleased to say: all three novellas we’re publishing from our inaugural prize are up there: Astraea, Aerth and We Hexed the Moon.

A Month in the Country might be the exemplar of the form for me. But there is a little-read novella by Tolstoy, Hadji Murat, which is also close to perfect. More contemporaneously, Gerald Murnane’s Border Districts. And I’m pleased to say: all three novellas we’re publishing from our inaugural prize are up there: Astraea, Aerth and We Hexed the Moon.

*Though it won’t be published until 25 January, I have a finished copy of the other winner, Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, a novella-in-flash set on alternative earths and incorporating second- and third-person narration and various formats. I’ve been enjoying it so far and hope to review it soon as my first recommendation for 2025.

A Journey through Chronic Pain: Heal Me by Julia Buckley

Julia Buckley can pinpoint the very moment when her battle with chronic pain began: it was a Tuesday morning in May 2012, and she was reaching across her desk for a cold cup of coffee. Although she had some underlying health issues, the “fire ants” down her arm and “carving knife” in her armpit? These were new. From there it just got worse: neck and back pain, swollen legs, and agonizing periods. Heal Me is a record of four years of chronic pain and the search for something, anything to take the pain away. “I couldn’t say no – that was a forbidden word on my journey. You never know who’s going to be your saviour.”

Having exhausted the conventional therapies available privately and via the NHS, most of which focus on cognitive behavioral therapy and coping strategies, Buckley quit work and registered as disabled. Ultimately she had to acknowledge that forces beyond the physiological might be at work. Despite her skepticism, she began to seek out alternative practitioners in her worldwide quest for a cure. Potential saviors included a guru in Vienna, traditional healers in Bali and South Africa, a witch doctor in Haiti, an herbalist in China, and a miracle worker in Brazil. She went everywhere from Colorado Springs (for medical marijuana) to Lourdes (to be baptized in the famous grotto). You know she was truly desperate when you read about her bathing in the blood and viscera of a sacrificial chicken.

Having exhausted the conventional therapies available privately and via the NHS, most of which focus on cognitive behavioral therapy and coping strategies, Buckley quit work and registered as disabled. Ultimately she had to acknowledge that forces beyond the physiological might be at work. Despite her skepticism, she began to seek out alternative practitioners in her worldwide quest for a cure. Potential saviors included a guru in Vienna, traditional healers in Bali and South Africa, a witch doctor in Haiti, an herbalist in China, and a miracle worker in Brazil. She went everywhere from Colorado Springs (for medical marijuana) to Lourdes (to be baptized in the famous grotto). You know she was truly desperate when you read about her bathing in the blood and viscera of a sacrificial chicken.

Now the travel editor of the Independent and Evening Standard, Buckley captures all these destinations and encounters in vivid detail, taking readers along on her rollercoaster ride of new treatment ideas and periodically dashed hopes. She is especially incisive in her accounting of doctors’ interactions with her. All too often she felt like a statistic or a diagnosis instead of a person, and sensed that her (usually male) doctors dismissed her as a stereotypically hysterical woman. Fat shaming came into the equation, too. Brief bursts of compassion, wherever they came from, made all the difference.

I was morbidly fascinated with this story, which is so bizarre and eventful that it reads like a great novel. I’ll be cheering it on in next year’s Wellcome Book Prize race.

My rating:

Heal Me: In Search of a Cure is published today, January 25th, by Weidenfeld & Nicolson. My thanks to the publisher for a free copy for review.

Julia graciously agreed to take part in a Q&A over e-mail. We talked about invisible disabilities, the gendered treatment of pain, and whether she believes in miracles.

“I spent a day at the Paralympic stadium with tens of thousands cheering on equality, but when it was time to go home, nobody wanted to give me a seat on the Central Line. I was, I swiftly realised, the wrong kind of disabled.”

Yours was largely an invisible disability. How can the general public be made more aware of these?

I feel like things are very, very gradually moving forward – speaking as a journalist, I know that stories about invisible disabilities do very well, and I think as we all try to be more “on” things and “woke” awareness is growing. But people are still cynical – Heathrow and Gatwick now have invisible disability lanyards for travellers and someone I was interviewing about it said “How do I know the person isn’t inventing it?” I think the media has a huge part to play in raising awareness, as do things like books (cough cough). And when trains have signs saying things like “be aware that not all disabilities are visible” on their priority seats, I think that’s a step forward. Openness helps, too, if people are comfortable about it – I’m a huge believer in oversharing.

“I wondered whether it was a peculiarly female trait to blame oneself when a treatment fails.”

You make a strong case for the treatment of chronic pain being gendered, and your chapter epigraphs, many from women writers who were chronic pain or mental health patients, back this up. There’s even a name for this phenomenon: Yentl Syndrome. Can you tell us a little more about that? What did you do to push back against it?

Yentl Syndrome is the studied phenomenon that male doctors are un/consciously sexist in their dealings with female patients – with regards to pain, they’re twice as likely to ascribe female pain to psychological reasons and half as likely to give them adequate painkillers. In the US, women have to cycle through 12 doctors, on average, before they find the one to treat their pain adequately. There are equally shocking stats if you look at race and class, too.

I did absolutely nothing to push back against it when I was being treated, to be honest, because I didn’t recognise what was going on, had never heard of Yentl Syndrome and thought it was my problem, not theirs. It was really only when I met Thabiso, my sangoma in South Africa, that I felt the scales lift from my eyes about what had been going on. I make up for it now, though – I recently explained to a GP what it was, and suggested he be tested for it (long story, but we were on the phone and he was being incredibly patronising and not letting me speak). He hung up on me.

“In my head I added, I don’t care what they do to me, as long as it helps the pain.”

Meatloaf sang, “I would do anything for love, but I won’t do that.” Can you think of anything you wouldn’t have done in the search for a cure?

Well, I refused a spiritual surgery from John of God – I would have had the medical clamp up my nose or happily been cut into, but I was phobic about having my eyeball scraped – I had visions of Un Chien Andalou. So I had said repeatedly I was up for the other stuff but wouldn’t do the eye-scraping, and was told that probably meant I’d get the eye-scraping so I should go for the “invisible” surgery instead. But I can’t think of anything else I wouldn’t have done. The whole point, for me, was that if I didn’t throw myself into something completely, if I didn’t get better I’d never know if that was the treatment not working or my fault. Equally, my life was worthless to me – I knew I would probably be dead if I didn’t find an answer, so I didn’t have anything to lose.

Having said that, I know I would have had major difficulties slaughtering a goat if I’d gone back to Thabiso – I’m not sure if I could even have asked anyone else to do that for me.

Looking back, do you see your life in terms of a clear before and after? Are you the same person as you were before you went through this chronic pain experience?

There’s definitely a clear before and after in terms of how I think of my life – before the accident and after it. The date is in my head and I measure everything in my life around that, whether that’s a work event, a holiday, anything else – it’s always XX months/years before or after the accident. I don’t have the same thing with the day I got better because I try not to think about what happened and why, so I still calculate everything around the accident even though I should probably try and move my life to revolve around that happier day.

Largely I’m the same person. I still have the same interests and the same job, so I haven’t changed in that way. But I’d say I’m more focused – I lost so much of my life that I’m trying to make up for it now. So I don’t watch TV, I don’t go out to anything I’m not really interested in, I didn’t go to the work Christmas party because I could think of better things to do than stand around sober shouting over music … so I’m more ruthless about how I spend my time.

I also think invisible illness – or people’s reaction to it – hardens you. You have to grow a shell, otherwise you wouldn’t get through it. So I’m probably more brusque. I’m also really fucking angry about how I was treated and how I see other people – especially other women – being treated and I know that low-level anger shows through a lot. But as I said to a friend (male, obviously) recently, when he read my book and was upset at my anger: once you start noticing what’s going on, when you see people’s lives ruined because of pain, when in extreme cases you see women dying because of their gender, how can you not be angry? I think we should all be more angry. Maybe we could get more done.

You got a book contract before you’d completed all the travel. At that point you didn’t know what the conclusion of your quest would be: a cure, or acceptance of chronic pain as your new normal. Given that uncertainty, how did you go about shaping this narrative?

For the proposal for the book I did a country-by-country, treatment-by-treatment chapter plan (it was wildly ambitious, but pain and finances put the dampeners on it) and suggested the last chapter would be at a meditation retreat in Dorset, learning acceptance. I put in some waggish comment like “assuming I don’t get cured first hahaha”, but secretly I knew there was no way I could write the book if I wasn’t cured, partly on a very literal level – I physically wouldn’t be able to do it – but more because I didn’t see how I would ever be able to accept it. I actually postponed the deadline twice for the same reasons, and when I realised deadline 3 was looming and I wasn’t better and I was going to have to suck it up and write it I was distraught. I genuinely thought that putting all that I had been through onto the page and having to admit that I had failed – and failed my fellow pain people I was doing it for – would kill me. So I don’t know what I would have done if it had come to the crunch; luckily I got my pot of white chrysanthemums and didn’t have to see what happened.

You are leery of words like “miracle” and “cure,” so what terms might you use to describe what ended your pain after four years?

Something happened, and it happened in Brazil. But I would never tell anyone to hop on a plane to Brazil. What happened to me happened after four years of soul-searching and introspection as well as all those treatments. If I’d gone to Brazil first, I don’t know what would have happened.

Who do you see being among the audience for your book?

I’d love people who need it to read it and take what they need from it, but I’d also love doctors to read it – as an insight into patient psychology if nothing else – and I’d love it to be seen as a continuation of the whole #MeToo debate. That sounds holier than thou, and obviously it’d be great for people to read it as a Jon-Ronson-meets-Elizabeth-Gilbert-style romp because I’d feel like I’d succeeded from a writing point of view, but to be honest the only reason I wanted to write it in the first place was to show what’s happening to people in pain, and once I got better, the only thing that mattered to me was getting it into the hands of people who need it. I know how much I needed something like this.

I appreciated the variety of forms and voices here. One story set in a dystopian future has an epistolary element, including letters and memos; two others use second-person or first-person plural narration, respectively. There’s also a lot to think about in terms of gender. For instance, one protagonist frets about out-of-control pubic hair, while another finds it difficult to maintain her trans identity on a male prison ward. “A Real Live Baby” was a stand-out for me. Its title is a tease, though, because Chloe is doing the Egg Baby project in school and ‘babysits’ for her delusional neighbor, who keeps a doll in a stroller. The conflation of dolls and babies is also an element in recent stories by

I appreciated the variety of forms and voices here. One story set in a dystopian future has an epistolary element, including letters and memos; two others use second-person or first-person plural narration, respectively. There’s also a lot to think about in terms of gender. For instance, one protagonist frets about out-of-control pubic hair, while another finds it difficult to maintain her trans identity on a male prison ward. “A Real Live Baby” was a stand-out for me. Its title is a tease, though, because Chloe is doing the Egg Baby project in school and ‘babysits’ for her delusional neighbor, who keeps a doll in a stroller. The conflation of dolls and babies is also an element in recent stories by