Literary Connections in Whitby

This past weekend marked my second trip to Whitby in North Yorkshire, more than 10 years after my first. It was, appropriately, on the occasion of a 10-year anniversary – namely, of the existence of Emmanuel Café Church, an informal group based at the University of Leeds chaplaincy center that I was involved in during my master’s year in 2005–6. I was there for the very first year and it was a welcome source of friendship during a tough year of loneliness and homesickness, so it’s gratifying that it’s still going nearly 11 years later (but also scary that it’s all quite that long ago). The reunion was held at Sneaton Castle, a lovely venue with a resident order of Anglican nuns that’s about a half-hour walk from central Whitby.

Sneaton Castle and grounds

Whitby harbor, with St. Mary’s Church on the hill.

The more I think about it, Leeds was a fine place to do a Victorian Literature degree – it’s not too far from Haworth, the home of the Brontës, or Whitby, a setting used in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Two of my classmates and I made our own pilgrimages to both sites in 2006. The Whitby Abbey ruins rising above the churchyard of St. Mary’s certainly create a suitably creepy atmosphere. No wonder Whitby is enduringly popular with Goths and at Halloween.

Another resident of Victorian Whitby, unknown to me until I saw a plaque designating her cottage on the walk from Sneaton into town, was Mary Linskill (1840–91), who wrote short stories and novels including Between the Heather and the Northern Sea (1884), The Haven under the Hill (1886) and In Exchange for a Soul (1887). I checked Project Gutenberg and couldn’t find a trace of her work, but the University of Reading holds a copy of her Tales of the North Riding in their off-site store. Perhaps I’ll have a gander!

There are other connections to be made with Whitby, too. For one thing, it has a long maritime history: it was home to William Scoresby (“Whaler, Arctic Voyager and Inventor of the Crow’s Nest,” as the plaque outside his house reads), and Captain James Cook grew up 30 miles away and served an apprenticeship in the town. There’s a statue of Cook plus a big whalebone arch on the hill the other side of the harbor from the church and abbey. It felt particularly fitting that I’ve been reading A.N. Wilson’s forthcoming novel Resolution, about the naturalists who sailed on Captain Cook’s second major expedition in the 1770s.

There are other connections to be made with Whitby, too. For one thing, it has a long maritime history: it was home to William Scoresby (“Whaler, Arctic Voyager and Inventor of the Crow’s Nest,” as the plaque outside his house reads), and Captain James Cook grew up 30 miles away and served an apprenticeship in the town. There’s a statue of Cook plus a big whalebone arch on the hill the other side of the harbor from the church and abbey. It felt particularly fitting that I’ve been reading A.N. Wilson’s forthcoming novel Resolution, about the naturalists who sailed on Captain Cook’s second major expedition in the 1770s.

(My other apt reading for the sunny August weekend was Vanessa Lafaye’s Summertime.)

On our Sunday afternoon browse of Whitby’s town center we couldn’t resist a stop into a bargain bookshop, where my husband bought a cheap copy of David Lebovitz’s all-desserts cookbook; I picked up a classy magnetic bookmark and a novel I’d never heard of for a grand total of £1.09. I know nothing about Dirk Wittenborn’s Pharmakon, but this 10 pence paperback comes with high praise from Lionel Shriver, Bret Easton Ellis and the Guardian, so I’ll give it a try and let you know how it works out in terms of literary value for money!

Have you explored any literary destinations recently? What have you been reading on summer weekends?

European Traveling and Reading

We’ve been back from our European trip for over a week already, but I haven’t been up to writing until now. Partially this is because I’ve had a mild stomach bug that has left me feeling yucky and like I don’t want to spend any more time at a computer than is absolutely necessary for my work; partially it’s because I’ve just been a bit blue. Granted, it’s nice to be back where all the signs and announcements are in English and I don’t have to worry about making myself understood. Still, gloom over Brexit has combined with the usual letdown of coming back from an amazing vacation and resuming normal life to make this a ho-hum sort of week. Nonetheless, I want to get back into the rhythm of blogging and give a quick rundown of the books I read while I was away.

Tiny Lavin station, our base in southeastern Switzerland.

But first, some of the highlights of the trip:

- the grand architecture of the center of Brussels; live jazz emanating from a side street café

- cycling to the zoo in Freiburg with our friends and their kids

- ascending into the mountains by cable car and then on foot to circle Switzerland’s Lake Oeschinensee

- traipsing through meadows of Alpine flowers

- exploring the Engadine Valley of southeast Switzerland, an off-the-beaten track, Romansh-speaking area where the stone buildings are covered in engravings, paintings and sayings

- our one big splurge of the trip (Switzerland is ridiculously expensive; we had to live off of supermarket food): a Swiss dessert buffet followed by a horse carriage ride

- spotting ibex and chamois at Oeschinensee and marmots in the Swiss National Park

- miming “The Hills Are Alive” in fields near our accommodation in Austria (very close to where scenes from The Sound of Music were filmed)

- the sun coming out for our afternoon in Salzburg

- daily coffee and cake in Austrian coffeehouses

- riding the underground and trams of Vienna’s public transport network

- finding famous musicians’ graves in Vienna’s Zentralfriedhof cemetery

- discovering tasty vegan food at a hole-in-the-wall Chinese restaurant in Vienna that makes its own noodles

- going to Slovakia for the afternoon on a whim (its capital, Bratislava, is only 1 hour from Vienna by train – why not?!)

We went to such a variety of places and had so many different experiences. Weather and language were hugely variable, too: it rained nine days in a row; some mornings in Switzerland I wore my winter coat and hat; in Bratislava it was 95 °F. Even in the ostensibly German-speaking countries of the trip, we found that greetings and farewells changed everywhere we went (doubly true in the Romansh-speaking Engadine). Most of the time we had no idea what shopkeepers were saying to us. Just smile and nod. It was more difficult at the farm where we stayed in Austria. Thanks to Google Translate, we had no idea that the owner spoke no English; her e-mails were all in unusual but serviceable English. We speak virtually no German, so fellow farm guests, including a Dutch couple, had to translate between us. (The rest of Europe puts us to shame with their knowledge of languages!)

A reading-themed art installation at the Rathaus in Basel, Switzerland.

Train travel was, for the most part, easy and stress-free. Especially enjoyable were the small lines through the Engadine, which include the highest regular-service station in Europe (Ospizia Bernina, where we found fresh snowfall). The little town where we stayed in an Airbnb cabin, Lavin, was a request stop on the line, meaning you always had to press a button to get the train to stop and then walk across the tracks (!) to board. Contrary to expectations, we found that nearly all of our European trains were running late. However, they were noticeably more comfortable than British trains, especially the German ones. Thanks to train rides of an hour or more on most days, I ended up getting a ton of reading done.

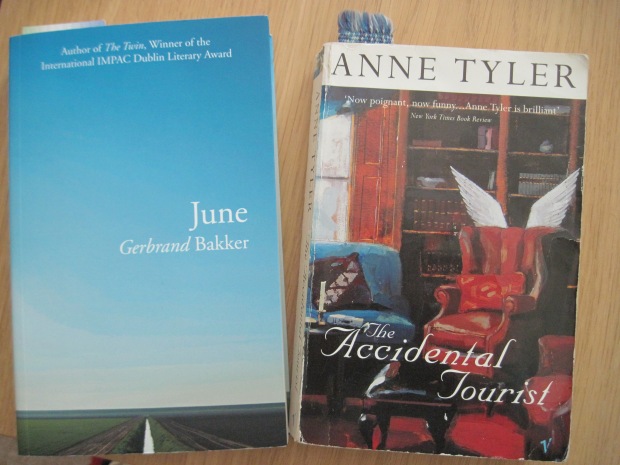

On the journey out I finished The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler. This is the first “classic” Tyler I’ve read, after her three most recent novels, and although I kept being plagued by odd feelings of ‘reverse déjà vu’, I really enjoyed it. This story of staid, reluctant traveler Macon Leary and how his life is turned upside down by a flighty dog trainer is all about the patterns of behavior we get stuck in. Tyler suggests that occasionally journeying into someone else’s unpredictable life might change ours for the good.

On the journey out I finished The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler. This is the first “classic” Tyler I’ve read, after her three most recent novels, and although I kept being plagued by odd feelings of ‘reverse déjà vu’, I really enjoyed it. This story of staid, reluctant traveler Macon Leary and how his life is turned upside down by a flighty dog trainer is all about the patterns of behavior we get stuck in. Tyler suggests that occasionally journeying into someone else’s unpredictable life might change ours for the good.

Diary of a Pilgrimage by Jerome K. Jerome was just what I expected: a very silly book about the travails of international travel. It’s much more about the luckless journey and the endurance of national stereotypes than it is about the Passion Play the travelers see once they get to Germany. It was amusing to see the ways in which some things have hardly changed in 125 years.

Diary of a Pilgrimage by Jerome K. Jerome was just what I expected: a very silly book about the travails of international travel. It’s much more about the luckless journey and the endurance of national stereotypes than it is about the Passion Play the travelers see once they get to Germany. It was amusing to see the ways in which some things have hardly changed in 125 years.

A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler, a novella set in the Austrian Alps, is the story of Andreas Egger – at various times a farmer, a prisoner of war, and a tourist guide. Various things happen to him, most of them bad. I have trouble pinpointing why Stoner is a masterpiece whereas this is just kind of boring. There’s a great avalanche scene, though.

A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler, a novella set in the Austrian Alps, is the story of Andreas Egger – at various times a farmer, a prisoner of war, and a tourist guide. Various things happen to him, most of them bad. I have trouble pinpointing why Stoner is a masterpiece whereas this is just kind of boring. There’s a great avalanche scene, though.

The Book that Matters Most by Ann Hood releases on August 9th. A new book club helps Ava cope with her divorce, her daughter Maggie’s rebelliousness, and tragic events from her past. Each month one club member picks the book that has mattered most to them in life. I thought the choices were all pretty clichéd and Ava was unrealistically passive. Although what happens to her in Paris is rather melodramatic, I most enjoyed Maggie’s sections.

The Book that Matters Most by Ann Hood releases on August 9th. A new book club helps Ava cope with her divorce, her daughter Maggie’s rebelliousness, and tragic events from her past. Each month one club member picks the book that has mattered most to them in life. I thought the choices were all pretty clichéd and Ava was unrealistically passive. Although what happens to her in Paris is rather melodramatic, I most enjoyed Maggie’s sections.

Me and Kaminski was my second novel from Daniel Kehlmann. Know-nothing art critic Sebastian Zöllner interviews reclusive artist Manuel Kaminski and then accompanies the older man on a road trip to find his lost sweetheart. Zöllner is an amusingly odious narrator, but I found the plot a bit thin. This is a rare case where I would argue the book needs to be 100 pages longer.

Me and Kaminski was my second novel from Daniel Kehlmann. Know-nothing art critic Sebastian Zöllner interviews reclusive artist Manuel Kaminski and then accompanies the older man on a road trip to find his lost sweetheart. Zöllner is an amusingly odious narrator, but I found the plot a bit thin. This is a rare case where I would argue the book needs to be 100 pages longer.

About midway through the trip I finished another I’d started earlier in the month, This Is Where You Belong by Melody Warnick. The average American moves 11.7 times in their life. I’m long past that already. The book collects an interesting set of ideas about how to feel at home wherever you are: things like learning the place on foot, shopping and eating locally, and getting to know your neighbors. I am bad about integrating into a new community every time we move, so I picked up some good tips. Warnick uses examples from all over (though mostly U.S. locations), but also makes it specific to her home of Blacksburg, Virginia.

About midway through the trip I finished another I’d started earlier in the month, This Is Where You Belong by Melody Warnick. The average American moves 11.7 times in their life. I’m long past that already. The book collects an interesting set of ideas about how to feel at home wherever you are: things like learning the place on foot, shopping and eating locally, and getting to know your neighbors. I am bad about integrating into a new community every time we move, so I picked up some good tips. Warnick uses examples from all over (though mostly U.S. locations), but also makes it specific to her home of Blacksburg, Virginia.

“A cabinet of fantasies, a source of knowledge, a collection of lore from past and present, a place to dream… A bookshop can be so many things.” In A Very Special Year by Thomas Montasser, Valerie takes over Ringelnatz & Co. bookshop when the owner, her Aunt Charlotte, disappears. She has the entrepreneurial skills to run a business and gradually develops a love of books, too. The title book is a magical tome with blank pages that reveal the reader’s destination when the time is right. Twee but enjoyable; a quick read.

“A cabinet of fantasies, a source of knowledge, a collection of lore from past and present, a place to dream… A bookshop can be so many things.” In A Very Special Year by Thomas Montasser, Valerie takes over Ringelnatz & Co. bookshop when the owner, her Aunt Charlotte, disappears. She has the entrepreneurial skills to run a business and gradually develops a love of books, too. The title book is a magical tome with blank pages that reveal the reader’s destination when the time is right. Twee but enjoyable; a quick read.

Eleven Hours by Pamela Erens is a taut thriller set during one woman’s experience of childbirth in New York City in 2004. Flashbacks to how the patient and her Caribbean nurse got where they are now add emotional depth. Another very quick read.

Eleven Hours by Pamela Erens is a taut thriller set during one woman’s experience of childbirth in New York City in 2004. Flashbacks to how the patient and her Caribbean nurse got where they are now add emotional depth. Another very quick read.

Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig is a psychologically astute novella in which a 12-year-old tries to interpret what’s happening between his mother and a fellow hotel guest, a baron he looks up to. For this naïve boy, many things come as a shock, including the threat of sex and the possibility of deception. This reminded me most of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. (On a hill above Salzburg we discovered a strange disembodied bust of Stefan Zweig, along with a plaque and a road sign.)

Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig is a psychologically astute novella in which a 12-year-old tries to interpret what’s happening between his mother and a fellow hotel guest, a baron he looks up to. For this naïve boy, many things come as a shock, including the threat of sex and the possibility of deception. This reminded me most of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. (On a hill above Salzburg we discovered a strange disembodied bust of Stefan Zweig, along with a plaque and a road sign.)

Playing Dead by Elizabeth Greenwood (releases August 9th) was great fun. Thinking of the six-figure education debt weighing on her shoulders, she surveys various cases of people who faked their own death or simply tried to disappear. Death fraud/“pseudocide” is not as easy to get away with as you might think. Fake drownings are especially suspect. I found most ironic the case of a man who lived successfully for 20 years under an assumed name but was caught when police stopped him for having a license plate light out. I particularly liked the chapter in which Greenwood travels to the Philippines, a great place to fake your death, and comes back with a copy of her own death certificate.

Playing Dead by Elizabeth Greenwood (releases August 9th) was great fun. Thinking of the six-figure education debt weighing on her shoulders, she surveys various cases of people who faked their own death or simply tried to disappear. Death fraud/“pseudocide” is not as easy to get away with as you might think. Fake drownings are especially suspect. I found most ironic the case of a man who lived successfully for 20 years under an assumed name but was caught when police stopped him for having a license plate light out. I particularly liked the chapter in which Greenwood travels to the Philippines, a great place to fake your death, and comes back with a copy of her own death certificate.

Miss Jane by Brad Watson (releases July 12th) is a historical novel loosely based on the story of the author’s great-aunt. Born in Mississippi in 1915, she had malformed genitals, which led to lifelong incontinence. Jane is a wonderfully plucky protagonist, and her friendship with her doctor, Ed Thompson, is particularly touching. “You would not think someone so afflicted would or could be cheerful, not prone to melancholy or the miseries.” This reminded me most of What Is Visible by Kimberly Elkins, an excellent novel about living a full life and finding romance in spite of disability.

Miss Jane by Brad Watson (releases July 12th) is a historical novel loosely based on the story of the author’s great-aunt. Born in Mississippi in 1915, she had malformed genitals, which led to lifelong incontinence. Jane is a wonderfully plucky protagonist, and her friendship with her doctor, Ed Thompson, is particularly touching. “You would not think someone so afflicted would or could be cheerful, not prone to melancholy or the miseries.” This reminded me most of What Is Visible by Kimberly Elkins, an excellent novel about living a full life and finding romance in spite of disability.

I also left two novels unfinished (that’ll be for another post) and made progress in two other nonfiction titles. All in all, a great set of reading!

I’m supposed to be making my way through just the books we already own for the rest of the summer, but when I got back of course I couldn’t resist volunteering for a few new books available through Nudge and The Bookbag. Apart from a few blog reviews I’m bound to, my summer plan will be to give the occasional quick roundup of what I’ve read of late.

What have you been reading recently?

European Holiday Reading – A (Temporary) Farewell

Tomorrow we’re off to continental Europe for two weeks of train travel, making stops in Brussels, Freiburg (Germany), two towns in Switzerland, and Salzburg and Vienna in Austria. This will be some of the most extensive travel I’ve done in Europe in the 11 or so years that I’ve lived here – and the first time I’ve been to Switzerland or Austria – so I’m excited. I’ve been working like a fiend recently to catch up and/or get ahead on reviews and blogs, so it will be particularly good to spend two weeks away from a computer. It’s also nice that our adventure doesn’t have to start with going to an airport.

Here’s what I’ve packed:

- Setting Free the Bears by John Irving (his first novel; set in Vienna)

- Diary of a Pilgrimage by Jerome K. Jerome (about a train journey from England to Germany)

- Me and Kaminski by Daniel Kehlmann (the author is Austrian)

- A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler (a novella set in the Austrian Alps)

+ Enchanting Alpine Flowers & the Rough Guide to Vienna

Also on the e-readers, downloaded from Project Gutenberg:

- Three Men on the Bummel by Jerome K. Jerome (further humorous antics in Germany)

- Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig (a novella; the author is Austrian)

+ another 250+ Kindle books from a wide variety of genres and topics – I’ll certainly have no shortage of reading material!

(Looking back now, it occurs to me that this all skews rather towards Austria! Oh well. Vienna is one of our longer stops.)

I’m supposed to be making my way through the books we already own, but on Saturday I was overcome with temptation at our local charity shop when I saw that all paperbacks were on sale – 5 for £1. I’m in the middle of one of the novels I bought that day, June by Gerbrand Bakker, along with The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler, and need to decide whether to put them on hold while I’m away or take one or both with me. Either way I’ll try to finish June this month; it’s just too appropriate not to!

I was also overcome with temptation at the thought of a new Eowyn Ivey novel coming out in August, so requested a copy for review.

It’s an odd time here in the UK. Readers from North America or elsewhere might be unaware that we’re gearing up for a referendum to decide whether to remain in the European Union. By the time we pass back through Brussels (‘capital’ of the European Union) on the 24th, there’s every chance the UK might no longer be an official member of Europe. I haven’t taken British citizenship so am ineligible to cast a vote; I won’t court debate by elaborating on a comparison of “Brexit” with the specter of Trump in the States. My husband has sent in his postal vote, so collectively we’ve done all we can do and now just have to wait and see.

We’re not back until late on the 24th, but I’ve scheduled a few posts for while we’re away. I will only have sporadic Internet access during these weeks, so won’t be replying to blog comments or reading fellow bloggers’ posts, but I promise to catch up when we get back.

Happy June reading!

When Is a Bookshop Not a Bookshop?

The answer to the riddle: when all the books are free! Christmas came early on Sunday when I visited a place I long knew of but had never visited: The Book Thing of Baltimore. It’s an entirely not-for-profit venture run with the help of volunteers and donations. “Our mission is to put unwanted books into the hands of those who want them,” says their website. My hubby and I were going into the city to meet friends for the day, so I suggested a quick run to Book Thing, a hidden treasure on an unassuming concrete lot that’s only open on the weekends.

I brought along a backpack crammed full of unwanted books from my old bedroom to donate, thinking that I would pick up just two or three in return. I was expecting one disorganized room full of pretty crummy books. To my delight, it was an enormous four-room warehouse with an amazing selection. A wonderful place to wander around and pick up things at random, but not great for seeking out particular titles given that the books – notably, fiction and biographies – are in no discernible alphabetical order.

Are you at all surprised to learn that I came away with a backpack just as overstuffed as I came with? At one point, as I was stacking up some terrific animal-themed books, my husband said, “You do realize you can only take what you can fit in your backpack? We’re going back by train!” My refrain was “but they’re all free!” I ended up with 31 books in total.

The haul.

I was especially thrilled with: The Fur Person, May Sarton’s book about cats, which I’d been hoping to find secondhand on this trip; Tigers in Red Weather, Ruth Padel’s travel book about searching for the world’s few remaining tigers in all their known habitats – I’d already read it but my husband hasn’t; Dakota by Kathleen Norris, a new favorite theology writer; Sara Nelson’s So Many Books, So Little Time (how apt!); and A Year by the Sea by Joan Anderson, which I’d never heard of but should fit right into my interest in women’s diaries.

Lest you think I’m some selfish book fiend, note that the pile on the left in the photograph below is for giving away to family and friends this Christmas. (Yes, I am aware that the pile of books we are keeping dwarfs the gift stack. Sigh.)

Dueling stacks.

All in all, it was a great day in Baltimore. We had a terrific lunch at City Café; browsed part of the amazing (and also free!) Walters Art Museum; toured the central campus of Johns Hopkins University, where my friend is a PhD student; walked through a small park; observed the shops and eateries of hipster Hampden; and saw the famous Christmas lights on 34th Street. They call it “Charm City,” and on Sunday it more than lived up to its name.

Book Thing is as sprawling as my favorite bookshop, Wonder Book (Frederick, Maryland), but you needn’t hand over any money. It’s as varied and tempting as any public library, but you don’t have to bring the books back. Nothing says “Merry Christmas” like free books!

Two Trips to the Theatre

Jane Eyre at the National Theatre

On October 3rd I was lucky enough to see a new production of Jane Eyre at London’s National Theatre. Thanks to theatre vouchers I had lying around, I paid all of £8 for my back-row seat, from which I had an excellent view, especially thanks to the pair of mini binoculars. Ten actors and musicians share all the roles. Sometimes a change of dress or hat is all that makes the distinction. For instance, the same actress (Laura Elphinstone) plays Helen Burns, Grace Poole, Adèle Varens, and St. John Rivers. One actor even plays Pilot the dog. His persistent “whoo-whoo” bark and habit of flopping at people’s feet make for charming comedy.

But the play belongs, of course, to Jane, and Madeleine Worrall is perfectly cast: unassuming yet passionate, a little firebrand. I can’t say for certain, but my impression is that she never leaves the stage during the entire production. She plays Jane at all ages: she voices a creepy baby cry when the bundle of cloth representing her infant self appears; other actors help her in and out of various dresses over a simple white shift as she grows up. The addition of a corset and petticoat indicates that she is now an adult, and a wedding dress and veil are the symbols of true love dangled before her eyes and then snatched away.

Set, props and music are all used to great effect. The action takes place on a complex of boardwalks, staircases and ladders, and most of the props are also wood and metal: stools, crates and window frames moved around to model different settings. The multiple levels allow for comings and goings but also for subtle displays of power relations. Objects hanging from the ceiling help to create location – family portraits and ominous red lighting signify Gateshead (the Reed house), simple sacking garments characterize Lowood School, and window frames and bare bulbs that flicker to Bertha’s laughs quite effectively evoke Thornfield Hall.

There is live musical backing at many points, with a piano, guitar, double bass and drums tucked off center under one of the boardwalks. The music ranges from instrumentals that wouldn’t be out of place in Downton Abbey or The Lord of the Rings to pop songs. An opera singer in a red satin dress wanders around singing snatches of folk spirituals and contemporary numbers. I certainly didn’t expect to hear Cee Lo Green’s “Crazy” during an adaptation of a nineteenth-century novel, but somehow it fits brilliantly.

The play is admirably true to the book. The two climactic fire scenes work very well, better than one might expect, and the romantic moments between Jane and Rochester are touchingly believable. I especially liked how journeys are suggested: a huddle of actors stand in the center of the stage and run in place to a percussion backing and a chant of destinations. One coach journey is even interrupted by a ‘piddle break’! Deaths are marked by opening a trap door near the edge of the stage and a character slowly descending some stairs out of sight.

The play started life in Bristol as a two-part adaptation stretching to four hours; for its move to London it has been condensed to just over three hours, but this still feels long, especially towards the end of the first act or in the aftermath of the revelation about Bertha. The St. John material, especially, drags – though that is true of the book as well. My main criticism of the production would be the way it sometimes tries to externalize Jane’s thoughts by having her ‘talk to herself’ via three or four other actors arguing. An angsty monologue à la Hamlet would have done the job just fine. Revealing Jane’s feelings for Rochester through a performance of the song “Mad About the Boy” likewise struck me as unsubtle.

![Painted by Evert A. Duyckinck, based on a drawing by George Richmond [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons/](https://bookishbeck.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/charlotte_bronte_coloured_drawing.png?w=620)

Charlotte Brontë. Painted by Evert A. Duyckinck, based on a drawing by George Richmond [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

A big anniversary is coming up: 2016 is the bicentennial of Charlotte Brontë’s birth. I’ve noticed a cluster of books being published or reissued in advance of her 200th birthday, such as Claire Harman’s biography, which I’ll review for For Books’ Sake, and a novel translated from the Dutch about Emily and Charlotte’s time in Belgium, Charlotte Brontë’s Secret Love by Jolien Janzing, which I’ll read for The Bookbag. There could be no better time for going back to her timeless stories, whether through the books themselves or another artistic expression.

To compare the thoughts of some professional theatregoers and see a few photos, check out the reviews on the Guardian and Telegraph websites.

When We Are Married by the Twyford & Ruscombe Players

J.B Priestley (1894–1984) is not a very familiar name for me, but my husband assures me he’s well known and loved here in England, if only for the play An Inspector Calls, which he studied at GCSE (it’s still a set text) and saw on stage. When We Are Married, one of the prolific Yorkshire author’s many plays, was first performed in 1938, though it’s set in 1908. I went to see it in our local village hall this past Saturday night.

The premise is simple: three couples (the Helliwells, Parkers and Soppitts) are celebrating their silver wedding anniversary, having all been married in the same chapel on the same morning. They even have a photo commemorating the occasion, and today they hope to recreate that shot. Over the years they have done well for themselves: one man is an alderman and another a counsellor; all three are heavily involved in their local chapel.

Press photograph of the original 1938 production: (clockwise from top left) Raymond Huntley, Lloyd Pearson, Ernest Butcher, Ethel Coleridge, Muriel George, and Helena Pickard. (From “The World of the Theatre,” Illustrated London News, 5 November 1938.)

All is not well in this small Yorkshire village, however. They are disappointed with their newly hired organist, a la-di-da southerner named Gerald Forbes who has been seen stepping out with young ladies at night. The whole play takes place in the drawing room of Alderman Helliwell’s home, and in an early scene the three gentlemen summon Gerald with the intention of dismissing him. However, he has his own surprise: a letter from the parish’s former parson, confessing that he wasn’t properly licensed to perform wedding ceremonies at the time. Consequently, these three pillars of the community are not legally married after all.

The news soon gets out thanks to a sullen cook who was listening behind the door and broadcasts the story at the local pub. In Act II the couples – including Gerald and his secret sweetheart, the Helliwells’ niece – take it in turns to come on stage for private chats. They spend time imagining what could be different in their lives if they really were single. Henpecked Herbert Soppitt gets his own back after years of cowering, while Mrs. Parker finally tells the Counsellor how dull and stingy she’s always found him to be.

The two best characters are Ruby Birtle, the Helliwells’ garrulous maid, and Henry Ormonroyd, a drunken photographer sent by the Yorkshire Argus. He functions like the Fool in this Shakespearean comedy of reversals, and happens to have some of the most profound lines. Will these unlucky couples get their anniversary photograph after all?

This was an enjoyable local production. The simple set was easy to maintain, and the acting – especially the Yorkshire accents – unimpeachable. The audience was in three sections in a rough semicircle around the action; my chair was just five feet behind a chaise longue on set. My only criticism would be that one of the three wives looked 20 years younger than the rest. I’ll certainly venture out for another show by the Twyford & Ruscombe Players.

Literary Tourism in Dublin

Almost immediately after our trip to Manchester (see my write-up of the literary destinations), we left again for Dublin, where my husband was attending a Royal Entomological Society conference. Like we did last year when he presented a poster at a conference in Florence, I went along since we only had to pay for my flight and meals.

We stayed north of the Liffey at one of the branches of Jurys Inn. For some reason they put us in a disabled room, which meant the bathroom was a bit odd, but I can’t complain about the breakfast buffet, which included black pudding, soda bread, fruit scones, and particularly delicious porridge.

Across the street was the terrific Chapters bookstore, with extensive secondhand and new stock. I highly recommend the Lonely Planet guide to Dublin, which provided my maps and many of my ideas for the week; I even managed to do 8 of their 10 recommended activities.

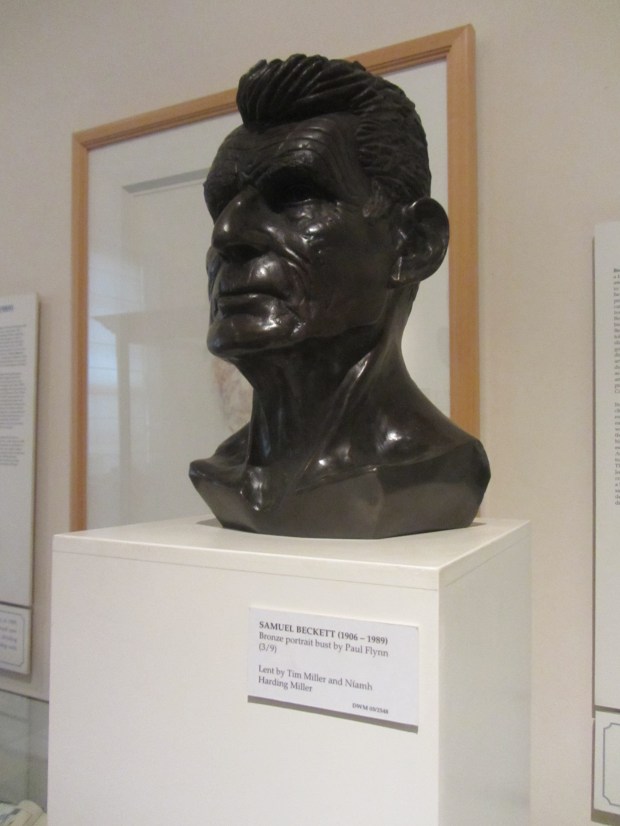

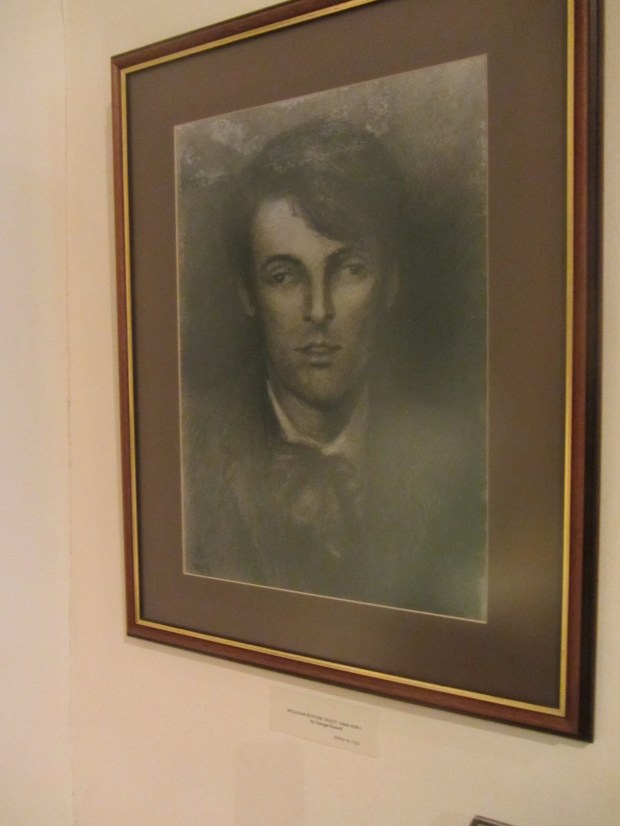

On Wednesday I wandered just a few minutes down the road to the Dublin Writers’ Museum. An audio guide takes you through the chronological displays about minor figures as well as the big names like W.B. Yeats, Oscar Wilde, and George Bernard Shaw. One caveat: only dead writers are considered; the museum is definitely missing a trick there – they could easily fill another room with living authors.

On the whole I found the place looking a bit shabby nowadays, but I passed a pleasant hour and a half here before popping a few doors down to the Dublin City Gallery, where they have multiple paintings by Jack B. Yeats (William Butler’s brother) as well as gems like a Monet and a Monet.

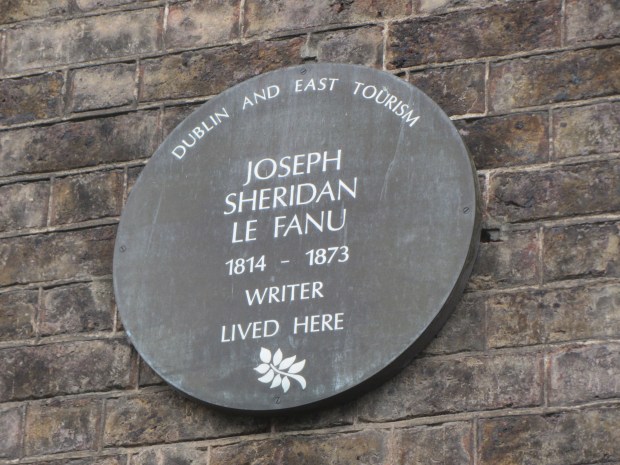

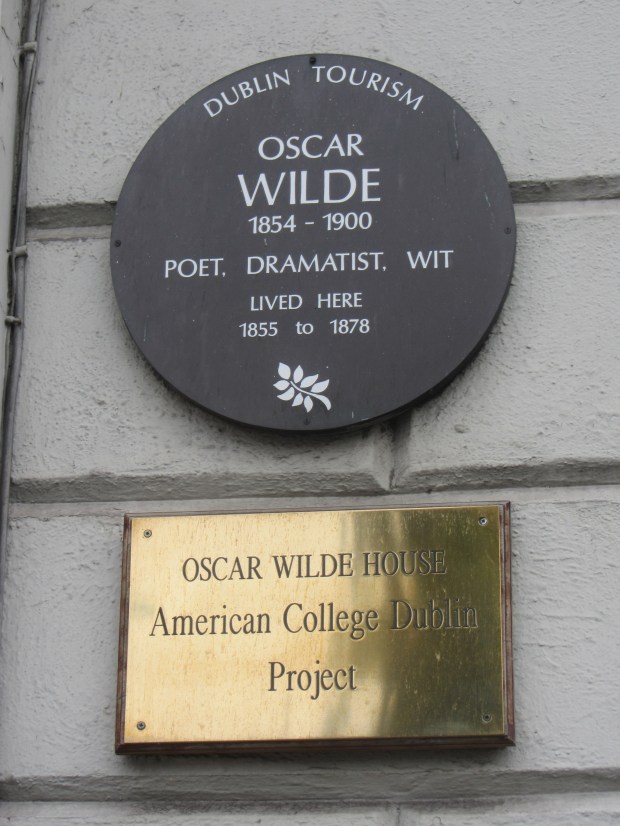

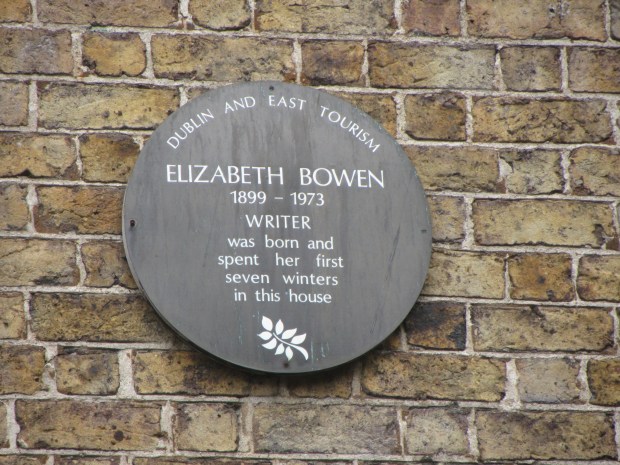

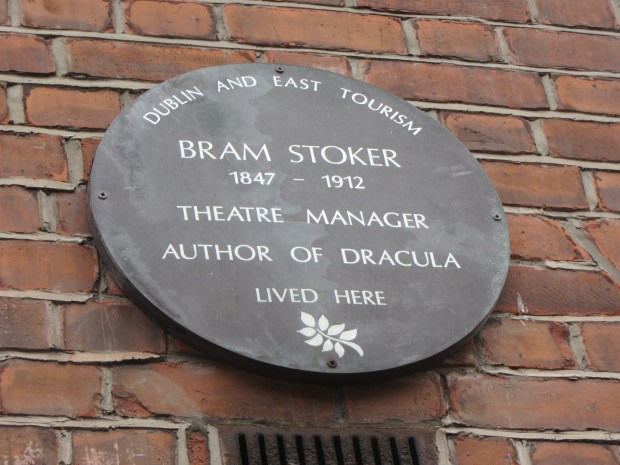

On Thursday I used the DK guide for a recommended walk through literary and Georgian Dublin. Along the way I discovered plaques to Yeats, Wilde (his home is now the headquarters of the American College and not open to the public, alas), ghost story writer Joseph Sheridan LeFanu, Bram Stoker, and Elizabeth Bowen, and a statue of poet Patrick Kavanagh by the canal. Fitzwilliam and Merrion Squares reminded me of London’s Bloomsbury Square (the latter houses a deliciously camp statue of Wilde), and St. Stephen’s Green would be a Hyde Park-type lovely spot for a sunny stroll – though it was drizzling and chilly as I walked through.

At the National Museum (Archaeology), I learned about Brian Boru, the national hero who kicked out the Vikings at the Battle of Clontarf and united the country.

My husband’s conference was at Trinity College, so he had a special chance to look in at the Old Library and the Book of Kells for a discounted price, but I didn’t end up going. On Thursday night we did something quintessentially Irish: found a pub with live traditional Irish folk music. Although we paid through the teeth for a pint of Guinness and a bottle of cider, it was an experience we wouldn’t have missed.

On Friday, after finishing up some reviewing work in the morning and checking out of the hotel, I returned to the Lonely Planet for a guided walk through Viking and medieval Dublin. The route took in the two cathedrals plus various other churches, ending up at the Castle and the Chester Beatty Library. I skipped the former but enjoyed a brief look at the rare books and manuscripts of the latter (mostly relating to the Far East, with a special focus on Asian religions) before walking back to the National Gallery to see the permanent collection.

That afternoon we moved on to Howth, a Dublin suburb only about 20 minutes away on the DART commuter train, but that somehow feels a world away: it’s a pleasant seaside village with heather- and gorse-covered hills and a lighthouse. It felt good to get out of the city – which was extremely busy and seemed to be mostly full of fellow tourists and the homeless – even if just for a little while.

This was our first Airbnb experience and turned out well after some unfortunate communication difficulties. Before settling in to our B&B we found a cheap and filling meal of fish and chips. The next day we explored the cliffs and met some friendly hooded crows before heading back into Dublin for a look at the wonderfully musty Natural History Museum and an excellent dinner at The Woollen Mills (interesting American fusion food: I had pork belly mac & cheese, and our dessert platter included an Oreo peanut butter tart).

My overall feeling was that Dublin still isn’t making as much of its literary heritage as it might do. I was perhaps not as impressed as I’d hoped to be – it’s a lot like London, and not as quaint as I might have expected. Still, I’m glad I went. Next time, though, I suspect we’ll go to less inhabited and more picturesque areas in the south and west.

I hadn’t the courage to face Joyce’s Ulysses or some other monolith of Irish literature, but I did continue Anne Enright’s The Green Road while in Dublin. I was also working on My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff, Of Human Bondage by W. Somerset Maugham (my current doorstopper), and The Heart Goes Last by Margaret Atwood.

Any comments about Ireland and its literary sites and/or heroes are most welcome!

Literary Tourism in Manchester

Over the August bank holiday weekend, my husband and I went to Manchester for the first time. Big cities aren’t our usual vacation destinations of choice, but we were going for the Sufjan Stevens gig at the O2 Apollo on the 31st and wanted to do the city justice while we were there, so stayed two nights at a chain hotel and worked out everything we wanted to see and do there, including two literary pilgrimages for me: Elizabeth Gaskell’s House and Chetham’s Library, where Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels met and discussed ideas in the summer of 1845. Armed only with a two-page map sliced out of an eleven-year-old Rough Guide, we felt perhaps a little ill-equipped, but managed to have a nice time nonetheless.

In preparation, I read The Communist Manifesto on the train ride north. It’s only 50 pages, and even with an introduction and multiple prefaces my Vintage Classics copy only comes to 70-some pages. That’s not to say it’s an easy read. I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the thread of the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. In fact, it had never occurred to me that this was first issued in Marx’s native German; like Darwin’s Origin of Species, another seminal Victorian text, it has so many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors that have entered into common discourse that I simply assumed it was composed in English.

After leaving our bags at the hotel on Sunday afternoon, we wandered over to the Gaskell House. It’s only open a few days a week, so we were lucky to be around during its opening hours. All of the house’s contents were sold at auction early in the twentieth century, so none of the furnishings are original, but the current contents have been painstakingly chosen to suggest what the house would have looked like at the time Gaskell and her family – a Unitarian minister husband and their four daughters – lived there. I especially enjoyed seeing William’s study and hearing how Charlotte Brontë hid behind the curtains in the drawing room so she wouldn’t have to socialize with the Gaskells’ visitors. The staff are knowledgeable and unfussy; unlike in your average National Trust house, they let you sit on the furniture and touch the objects. The gardens are also beautifully landscaped.

Talk about a contrast, though: look across the street and you see council housing and rubbish piled up on the pavement. In Gaskell’s time this was probably a genteel suburb, but now it’s an easy walk from the city center and in a considerably down-at-heel area. Indeed, we were taken aback by how grimy parts of Manchester were, and by how many homeless we encountered.

I’ve read four of Gaskell’s books: Mary Barton, North and South, Cranford and The Life of Charlotte Brontë. She’s not one of my favorite Victorian novelists, but I enjoyed each of those and intend to – someday – read Sylvia’s Lovers and Wives and Daughters, which was a few pages from completion when Gaskell died of a sudden heart attack in their second home in Hampshire, aged 55, in 1865.

Afterwards we stopped into the city’s Art Gallery and then headed to Mr Thomas’s Chop House for roast lamb and corned beef hash, then on to Sugar Junction to meet a blogger friend, the fabulous Lucy (aka Literary Relish), who I’d been corresponding with online for about two years but never met in real life. She graciously treated us to drinks and dessert at this cute café (one of the city’s many hip eateries) where she often hosts the Manchester Book Club, and we chatted about books and travel spots for a pleasant hour and a half.

On Monday we explored the Castlefield area with its canals and Roman ruins and went round both the Museum of Science and Industry and the People’s Museum, which together give a powerful sense of the city’s industrial and revolutionary past. We also toured the cathedral, took a peek at a Special Collections exhibit on the Gothic plus the main reading room at John Rylands Library, and browsed the huge selection at the main Waterstones branch. (On a future visit we are reliably informed that we must go find Sharston Books, a warehouse-scale secondhand shop out of town.) After a necessary pit stop for caffeine at The Foundation Coffee House and the best pizza we’ve ever had in the UK at Slice (including a Nutella and banana calzone for pudding), we headed over to the gig, which was terrific but not the purpose of this blog post.

Contrast between old and new Manchester: the hideous Beetham Tower on the left and Roman ruins in the foreground.

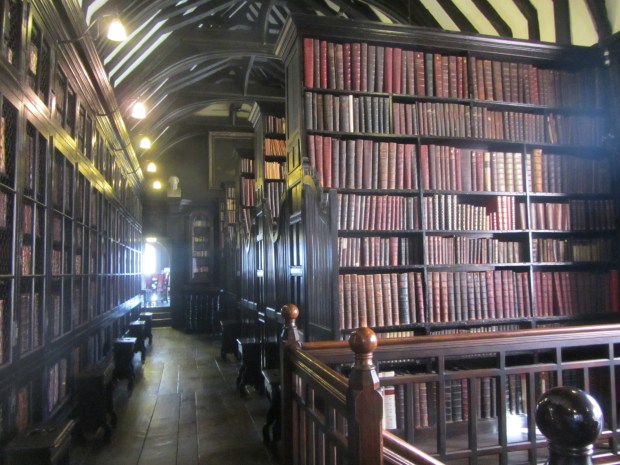

Our trip only spanned a Sunday and a bank holiday, so we missed seeing the inside of the hugely impressive Central Library and the 19th-century Portico Library. On Tuesday morning, though, we had just enough time before our train back to stop into Chetham’s Library. It’s a beautiful old library with rank after rank of leather-bound books sheltering amidst dark wood and mullioned windows. I love being in these kinds of places. They smell divine, and you can imagine holing up in a corner and reading all day, with the atmosphere beaming all kinds of lofty thoughts into your brain. We had the place to ourselves on this sunny morning and sat for a while in the bright alcove where Marx and Engels studied.

Apart from The Communist Manifesto, my reading on this trip was largely unrelated: My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff, a delightful literary memoir (review coming later this month); Number 11 by Jonathan Coe, a funny and mildly disturbing state-of-England and coming-of-age novel (releases November 11th); and The Mountain Can Wait by Sarah Leipciger, an atmospheric family novel set in the forests of Canada.

What have been some of your recent literary destinations? Do you like to read books related to the place you’re going, or do you choose your holiday reading at random?

After Me Comes the Flood was rejected by 14 publishers; even her viva examiners, who passed her without corrections, were “ungracious,” she remarked. What it comes down to, she thinks, is simply that no one liked the book or knew what to make of it. It seemed unmarketable because it didn’t fit into a particular genre. At this point I was sheepishly keeping my head down, glad that Perry couldn’t possibly know about my largely unfavorable review in Third Way magazine. I confess that my reaction was roughly similar to the general consensus: “Not quite an allegory, [the book] still suffers from that genre’s pitfalls, such as one-dimensional characters,” I wrote.

After Me Comes the Flood was rejected by 14 publishers; even her viva examiners, who passed her without corrections, were “ungracious,” she remarked. What it comes down to, she thinks, is simply that no one liked the book or knew what to make of it. It seemed unmarketable because it didn’t fit into a particular genre. At this point I was sheepishly keeping my head down, glad that Perry couldn’t possibly know about my largely unfavorable review in Third Way magazine. I confess that my reaction was roughly similar to the general consensus: “Not quite an allegory, [the book] still suffers from that genre’s pitfalls, such as one-dimensional characters,” I wrote. It will be interesting to see how she imagines a platonic friendship between the sexes in a historical setting, and the Dickensian and Gothic touches, even from the little taster I got, were delicious. I was especially intrigued to learn about her research into the friendship ‘triangle’ (betrayal! early death! forgiveness!) between William Ewart Gladstone, Alfred Tennyson, and Arthur Henry Hallam. Perry said she thinks the tide may be turning, that friendships rather than romantic love could be starting to dominate fiction; perhaps Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life from last year would be a good example.

It will be interesting to see how she imagines a platonic friendship between the sexes in a historical setting, and the Dickensian and Gothic touches, even from the little taster I got, were delicious. I was especially intrigued to learn about her research into the friendship ‘triangle’ (betrayal! early death! forgiveness!) between William Ewart Gladstone, Alfred Tennyson, and Arthur Henry Hallam. Perry said she thinks the tide may be turning, that friendships rather than romantic love could be starting to dominate fiction; perhaps Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life from last year would be a good example. In the other sessions I attended, a group of clergy revealed the shortlist for the £10,000

In the other sessions I attended, a group of clergy revealed the shortlist for the £10,000  Chaired by contemporary Anglican novelist

Chaired by contemporary Anglican novelist