Last House Before the Mountain by Monika Helfer (#NovNov23 and #GermanLitMonth)

This Austrian novella, originally published in German in 2020, also counts towards German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy Siddal. It is Helfer’s fourth book but first to become available in English translation. I picked it up on a whim from a charity shop.

“Memory has to be seen as utter chaos. Only when a drama is made out of it is some kind of order established.”

A family saga in miniature, this has the feel of a family memoir, with the author frequently interjecting to say what happened later or who a certain character would become, yet the focus on climactic scenes – reimagined through interviews with her Aunt Kathe – gives it the shape of autofiction.

Josef and Maria Moosbrugger live on the outskirts of an alpine village with their four children. The book’s German title, Die Bagage, literally means baggage or bearers (Josef’s ancestors were itinerant labourers), but with the connotation of riff-raff, it is applied as an unkind nickname to the impoverished family. When Josef is called up to fight in the First World War, life turns perilous for the beautiful Maria. Rumours spread about her entertaining men up at their remote cottage, such that Josef doubts the parentage of the next child (Grete, Helfer’s mother) conceived during one of his short periods of leave. Son Lorenz resorts to stealing food, and has to defend his mother against the mayor’s advances with a shotgun.

If you look closely at the cover, you’ll see it’s peopled with figures from Pieter Bruegel’s Children’s Games. Helfer was captivated by the thought of her mother and aunts and uncles as carefree children at play. And despite the challenges and deprivations of the war years, you do get the sense that this was a joyful family. But I wondered if the threats were too easily defused. They were never going to starve because others brought them food; the fending-off-the-mayor scenes are played for laughs even though he very well could have raped Maria.

Helfer’s asides (“But I am getting ahead of myself”) draw attention to how she took this trove of family stories and turned them into a narrative. I found that the meta moments interrupted the flow and made me less involved in the plot because I was unconvinced that the characters really did and said what she posits. In short, I would probably have preferred either a straightforward novella inspired by wartime family history, or a short family memoir with photographs, rather than this betwixt-and-between document.

(Bloomsbury, 2023. Translated from the German by Gillian Davidson. Secondhand purchase from Bas Books and Home, Newbury.) [175 pages]

Women in the Polar Night: Christiane Ritter and Sigri Sandberg

I’m continuing a Nonfiction November focus with reviews of two recently (re-)released memoirs about women spending time in the Arctic north of Norway. I enjoy reading about survival in extreme situations – it’s the best kind of armchair traveling because you don’t have to experience the cold and privation for yourself.

A Woman in the Polar Night by Christiane Ritter (1938; English text, 1954)

[Translated by Jane Degras]

In 1934, Ritter, an Austrian painter, joined her husband Hermann for a year in Spitsbergen. He’d participated in a scientific expedition and caught the Arctic bug, it seems, for he stayed on to fish and hunt. They shared a small, remote hut with a Norwegian trapper, Karl. Ritter was utterly unprepared for the daily struggle, having expected a year’s cozy retreat: “I could stay by the warm stove in the hut, knit socks, paint from the window, read thick books in the remote quiet and, not least, sleep to my heart’s content.” Before long she was disabused of her rosy vision. “It’s a ghastly country, I think to myself. Nothing but water, fog, and rain.” The stove failed. Dry goods ran out; they relied on fresh seal meat. Would they get enough vitamins? she worried. Every time Hermann and Karl set off hunting, leaving her alone in the hut, she feared they wouldn’t return. And soon the 132 straight days of darkness set in.

In 1934, Ritter, an Austrian painter, joined her husband Hermann for a year in Spitsbergen. He’d participated in a scientific expedition and caught the Arctic bug, it seems, for he stayed on to fish and hunt. They shared a small, remote hut with a Norwegian trapper, Karl. Ritter was utterly unprepared for the daily struggle, having expected a year’s cozy retreat: “I could stay by the warm stove in the hut, knit socks, paint from the window, read thick books in the remote quiet and, not least, sleep to my heart’s content.” Before long she was disabused of her rosy vision. “It’s a ghastly country, I think to myself. Nothing but water, fog, and rain.” The stove failed. Dry goods ran out; they relied on fresh seal meat. Would they get enough vitamins? she worried. Every time Hermann and Karl set off hunting, leaving her alone in the hut, she feared they wouldn’t return. And soon the 132 straight days of darkness set in.

I was fascinated by the details of Ritter’s daily tasks, but also by how her perspective on the landscape changed. No longer a bleak wilderness, it became a tableau of grandeur. “A deep blue-green, the mountains rear up into a turquoise-coloured sky. From the mountaintops broad glaciers glittering in the sun flow down into the fjord.” She thought of the Arctic almost as a site of spiritual pilgrimage, where all that isn’t elemental falls away. “Forgotten are all externals; here everything is concerned with simple being.” The year is as if outside of time: she never reminisces about her life back home, and barely mentions their daughter. By the end you see that the experience has changed her: she’ll never fret over trivial things again. She lived to age 103 (only dying in 2000), so clearly the time in the Arctic did her no harm.

I was fascinated by the details of Ritter’s daily tasks, but also by how her perspective on the landscape changed. No longer a bleak wilderness, it became a tableau of grandeur. “A deep blue-green, the mountains rear up into a turquoise-coloured sky. From the mountaintops broad glaciers glittering in the sun flow down into the fjord.” She thought of the Arctic almost as a site of spiritual pilgrimage, where all that isn’t elemental falls away. “Forgotten are all externals; here everything is concerned with simple being.” The year is as if outside of time: she never reminisces about her life back home, and barely mentions their daughter. By the end you see that the experience has changed her: she’ll never fret over trivial things again. She lived to age 103 (only dying in 2000), so clearly the time in the Arctic did her no harm.

Ritter wrote only this one book. A travel classic, it has never been out of print in German but has been for 50 years in the UK. Pushkin Press is reissuing the English text on the 21st with a foreword by Sara Wheeler, a few period photographs and a hand-drawn map by Neil Gower.

My rating:

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the free copy for review.

Notes: Michelle Paver drew heavily on this book when creating the setting for Dark Matter. (There’s even a bear post outside the Ritters’ hut.)

I found some photos of the Ritters’ hut here.

(Although I did not plan it this way, this book also ties in with German Literature Month!)

An Ode to Darkness by Sigri Sandberg (2019)

[Translated by Siân Mackie]

Ritter’s book is a jumping-off point for Norwegian journalist Sandberg’s investigation of darkness as both a physical fact and a cultural construct. She travels alone from her home in Oslo to her cabin in the mountains at Finse, 400 miles south of the Arctic Circle. Ninety percent of Norway’s wildlife sleeps through the winter, and she often wishes she could hibernate as well. Although she only commits to five days in the far north compared to Ritter’s year, she experiences the same range of emotions, starting with a primitive fear of nature and the dark.

It is a fundamental truth that darkness does not exist from an astronomical standpoint. Happy fact. I’m willing to accept this. I try to find it comforting, helpful. But I still struggle to completely believe that darkness does not actually exist. Because what does it matter to a small, poorly designed human whether darkness is real or perceived? And what about the black holes in the universe, what about dark matter, what about the night sky and the threats against it, and … and now I’m exhausted. I’m done for the day. I feel so small, and I’m tired of being afraid.

Over the course of the book she talks to scientists about the human need for sleep and sunshine, discusses solitude and dark sky initiatives, and quotes from a number of poets, especially Jon Fosse, “Norway’s greatest writer,” who often employs metaphors of light and dark: “Deep inside me / … it was like the empty darkness was shining”.

Over the course of the book she talks to scientists about the human need for sleep and sunshine, discusses solitude and dark sky initiatives, and quotes from a number of poets, especially Jon Fosse, “Norway’s greatest writer,” who often employs metaphors of light and dark: “Deep inside me / … it was like the empty darkness was shining”.

In occasional passages labeled “Christiane” Sandberg also recounts fragments of Ritter’s experiences. I read Sandberg’s book first, so these served as a tantalizing introduction to A Woman in the Polar Night. “Is there anywhere as silent as a white winter plateau on a windless day? And how long can anyone spend alone before they start to feel, like Christiane did, as if their very being is disintegrating?”

This is just the sort of wide-ranging nonfiction I love; it intersperses biographical and autobiographical information with scientific and cultural observations.

[Another recent book tries to do a similar thing but is less successful – partially due to the author’s youthful optimism, but also due to the rambly, shallow nature of the writing. (My

[Another recent book tries to do a similar thing but is less successful – partially due to the author’s youthful optimism, but also due to the rambly, shallow nature of the writing. (My  review will be in the November 29th issue of the Times Literary Supplement.)]

review will be in the November 29th issue of the Times Literary Supplement.)]

My rating:

With thanks to Sphere for the free copy for review.

Related reading: This Cold Heaven: Seven Seasons in Greenland by Gretel Ehrlich

Do you like reading about polar exploration, or life’s extremes in general?

German Lit Month: The Tobacconist by Robert Seethaler

I don’t participate in a lot of blogger challenges (though I’ll be doing “Novellas in November” on Monday); it’s more of a coincidence that I finished Austrian writer Robert Seethaler’s excellent The Tobacconist (translated from the German by Charlotte Collins) towards the end of German literature month.

You may recall that I read Seethaler’s previous novel, A Whole Life, on my European travels this past summer, and didn’t think too much of it. I’d read so much praise for its sparse style, but I couldn’t grasp the appeal. Here’s what I wrote about it at the time: “This novella set in the Austrian Alps is the story of Andreas Egger – at various times a farmer, a prisoner of war, and a tourist guide. Various things happen to him, most of them bad. I have trouble pinpointing why Stoner is a masterpiece whereas this is just kind of boring. There’s a great avalanche scene, though.”

But I’m very glad that I tried again with Seethaler, because The Tobacconist is one of the few best novels I’ve read this year, and very much a book for our times despite being set in 1937–8.

But I’m very glad that I tried again with Seethaler, because The Tobacconist is one of the few best novels I’ve read this year, and very much a book for our times despite being set in 1937–8.

Seventeen-year-old Franz Huchel’s life changes for good when his mother sends him away from his quiet lakeside village to work for her old friend Otto Trsnyek, a Vienna tobacconist. “In [Franz’s] mind’s eye the future appeared like the line of a far distant shore materializing out of the morning fog: still a little blurred and unclear, but promising and beautiful, too.”

Though the First World War left him with only one leg, Trsnyek is a firebrand. Instead of keeping his head down while selling his cigars and newspapers, he makes his political opinions known. This sees him branded as a “Jew lover” and persecuted accordingly. One of the Jews he dares to associate with is Sigmund Freud, who is a regular customer even though he already has throat cancer and will die just two years later.

Especially after he falls in love with Anezka, a flirtatious but mercurial Bohemian girl, Franz turns to Professor Freud for life advice. “So I’m asking you: have I gone mad? Or has the whole world gone mad?” The professor replies, “yes, the world has gone mad. And … have no illusions, it’s going to get a lot madder than this.”

Through free indirect speech, the thought lives of the various characters, and the postcards and letters that pass between Franz and his mother, Seethaler gradually and subtly reveals the deepening worry over the rise of Hitler and the situation of the Jews. This novel is so many things: a coming-of-age story, a bittersweet romance, an out-of-the-ordinary World War II/Holocaust precursor, and a perennially relevant reminder of the importance of finding the inner courage to stand up to oppressive systems.

Freud and his family had enough money and influence to buy their way to England. So many did not escape Hitler’s regime. I knew that, but discovered it anew in this outstanding novel.

Some favorite passages:

Dear Mother,

I’ve been here in the city for quite a while now, yet to be honest it seems to me that everything just gets stranger. But maybe it’s like that all through life—from the moment you’re born, with every single day, you grow a little bit further away from yourself until one day you don’t know where you are any more. Can that really be the way it is?

And as more than twenty thousand supporters bellowed their assent into the clear Tyrolean mountain air, Adolf Hitler was probably sitting beside the radio somewhere in Berlin, licking his lips. Austria lay before him like a steaming schnitzel on a plate. Now was the time to carve it up. … People were cosseting their faint-hearted troubles and hadn’t even noticed yet that the earth beneath their feet was burning.

(from a letter from Mama) Just imagine, Hitler hangs on the wall even in the restaurant and the school now. Right next to Jesus. Although we have no idea what they think of each other.

Freud: “Most paths do at least seem vaguely familiar to me. But it’s not actually our destiny to know the paths. Our destiny is precisely not to know them. We don’t come into this world to find answers, but to ask questions. We grope around, as it were, in perpetual darkness, and it’s only if we’re very lucky that we sometimes see a little flicker of light. And only with a great deal of courage or persistence or stupidity—or, best of all, all three at once—can we make our mark here and there, indicate the way.”

My rating:

Happy Thanksgiving to all my American readers! In previous years we’ve been able to find canned pumpkin in the UK to make a pumpkin pie, but alas, this year there have been supply issues (my husband blames Brexit). Nor can we find a real pumpkin – they disappear from the shops after Halloween. Without pumpkin pie it doesn’t feel much like Thanksgiving.

At any rate, here’s a flashback to the seasonal posts I wrote last year, one about five things I was grateful for as a freelance writer (they all still hold true!) and a list of recommended Thanksgiving reading.

European Traveling and Reading

We’ve been back from our European trip for over a week already, but I haven’t been up to writing until now. Partially this is because I’ve had a mild stomach bug that has left me feeling yucky and like I don’t want to spend any more time at a computer than is absolutely necessary for my work; partially it’s because I’ve just been a bit blue. Granted, it’s nice to be back where all the signs and announcements are in English and I don’t have to worry about making myself understood. Still, gloom over Brexit has combined with the usual letdown of coming back from an amazing vacation and resuming normal life to make this a ho-hum sort of week. Nonetheless, I want to get back into the rhythm of blogging and give a quick rundown of the books I read while I was away.

Tiny Lavin station, our base in southeastern Switzerland.

But first, some of the highlights of the trip:

- the grand architecture of the center of Brussels; live jazz emanating from a side street café

- cycling to the zoo in Freiburg with our friends and their kids

- ascending into the mountains by cable car and then on foot to circle Switzerland’s Lake Oeschinensee

- traipsing through meadows of Alpine flowers

- exploring the Engadine Valley of southeast Switzerland, an off-the-beaten track, Romansh-speaking area where the stone buildings are covered in engravings, paintings and sayings

- our one big splurge of the trip (Switzerland is ridiculously expensive; we had to live off of supermarket food): a Swiss dessert buffet followed by a horse carriage ride

- spotting ibex and chamois at Oeschinensee and marmots in the Swiss National Park

- miming “The Hills Are Alive” in fields near our accommodation in Austria (very close to where scenes from The Sound of Music were filmed)

- the sun coming out for our afternoon in Salzburg

- daily coffee and cake in Austrian coffeehouses

- riding the underground and trams of Vienna’s public transport network

- finding famous musicians’ graves in Vienna’s Zentralfriedhof cemetery

- discovering tasty vegan food at a hole-in-the-wall Chinese restaurant in Vienna that makes its own noodles

- going to Slovakia for the afternoon on a whim (its capital, Bratislava, is only 1 hour from Vienna by train – why not?!)

We went to such a variety of places and had so many different experiences. Weather and language were hugely variable, too: it rained nine days in a row; some mornings in Switzerland I wore my winter coat and hat; in Bratislava it was 95 °F. Even in the ostensibly German-speaking countries of the trip, we found that greetings and farewells changed everywhere we went (doubly true in the Romansh-speaking Engadine). Most of the time we had no idea what shopkeepers were saying to us. Just smile and nod. It was more difficult at the farm where we stayed in Austria. Thanks to Google Translate, we had no idea that the owner spoke no English; her e-mails were all in unusual but serviceable English. We speak virtually no German, so fellow farm guests, including a Dutch couple, had to translate between us. (The rest of Europe puts us to shame with their knowledge of languages!)

A reading-themed art installation at the Rathaus in Basel, Switzerland.

Train travel was, for the most part, easy and stress-free. Especially enjoyable were the small lines through the Engadine, which include the highest regular-service station in Europe (Ospizia Bernina, where we found fresh snowfall). The little town where we stayed in an Airbnb cabin, Lavin, was a request stop on the line, meaning you always had to press a button to get the train to stop and then walk across the tracks (!) to board. Contrary to expectations, we found that nearly all of our European trains were running late. However, they were noticeably more comfortable than British trains, especially the German ones. Thanks to train rides of an hour or more on most days, I ended up getting a ton of reading done.

On the journey out I finished The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler. This is the first “classic” Tyler I’ve read, after her three most recent novels, and although I kept being plagued by odd feelings of ‘reverse déjà vu’, I really enjoyed it. This story of staid, reluctant traveler Macon Leary and how his life is turned upside down by a flighty dog trainer is all about the patterns of behavior we get stuck in. Tyler suggests that occasionally journeying into someone else’s unpredictable life might change ours for the good.

On the journey out I finished The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler. This is the first “classic” Tyler I’ve read, after her three most recent novels, and although I kept being plagued by odd feelings of ‘reverse déjà vu’, I really enjoyed it. This story of staid, reluctant traveler Macon Leary and how his life is turned upside down by a flighty dog trainer is all about the patterns of behavior we get stuck in. Tyler suggests that occasionally journeying into someone else’s unpredictable life might change ours for the good.

Diary of a Pilgrimage by Jerome K. Jerome was just what I expected: a very silly book about the travails of international travel. It’s much more about the luckless journey and the endurance of national stereotypes than it is about the Passion Play the travelers see once they get to Germany. It was amusing to see the ways in which some things have hardly changed in 125 years.

Diary of a Pilgrimage by Jerome K. Jerome was just what I expected: a very silly book about the travails of international travel. It’s much more about the luckless journey and the endurance of national stereotypes than it is about the Passion Play the travelers see once they get to Germany. It was amusing to see the ways in which some things have hardly changed in 125 years.

A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler, a novella set in the Austrian Alps, is the story of Andreas Egger – at various times a farmer, a prisoner of war, and a tourist guide. Various things happen to him, most of them bad. I have trouble pinpointing why Stoner is a masterpiece whereas this is just kind of boring. There’s a great avalanche scene, though.

A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler, a novella set in the Austrian Alps, is the story of Andreas Egger – at various times a farmer, a prisoner of war, and a tourist guide. Various things happen to him, most of them bad. I have trouble pinpointing why Stoner is a masterpiece whereas this is just kind of boring. There’s a great avalanche scene, though.

The Book that Matters Most by Ann Hood releases on August 9th. A new book club helps Ava cope with her divorce, her daughter Maggie’s rebelliousness, and tragic events from her past. Each month one club member picks the book that has mattered most to them in life. I thought the choices were all pretty clichéd and Ava was unrealistically passive. Although what happens to her in Paris is rather melodramatic, I most enjoyed Maggie’s sections.

The Book that Matters Most by Ann Hood releases on August 9th. A new book club helps Ava cope with her divorce, her daughter Maggie’s rebelliousness, and tragic events from her past. Each month one club member picks the book that has mattered most to them in life. I thought the choices were all pretty clichéd and Ava was unrealistically passive. Although what happens to her in Paris is rather melodramatic, I most enjoyed Maggie’s sections.

Me and Kaminski was my second novel from Daniel Kehlmann. Know-nothing art critic Sebastian Zöllner interviews reclusive artist Manuel Kaminski and then accompanies the older man on a road trip to find his lost sweetheart. Zöllner is an amusingly odious narrator, but I found the plot a bit thin. This is a rare case where I would argue the book needs to be 100 pages longer.

Me and Kaminski was my second novel from Daniel Kehlmann. Know-nothing art critic Sebastian Zöllner interviews reclusive artist Manuel Kaminski and then accompanies the older man on a road trip to find his lost sweetheart. Zöllner is an amusingly odious narrator, but I found the plot a bit thin. This is a rare case where I would argue the book needs to be 100 pages longer.

About midway through the trip I finished another I’d started earlier in the month, This Is Where You Belong by Melody Warnick. The average American moves 11.7 times in their life. I’m long past that already. The book collects an interesting set of ideas about how to feel at home wherever you are: things like learning the place on foot, shopping and eating locally, and getting to know your neighbors. I am bad about integrating into a new community every time we move, so I picked up some good tips. Warnick uses examples from all over (though mostly U.S. locations), but also makes it specific to her home of Blacksburg, Virginia.

About midway through the trip I finished another I’d started earlier in the month, This Is Where You Belong by Melody Warnick. The average American moves 11.7 times in their life. I’m long past that already. The book collects an interesting set of ideas about how to feel at home wherever you are: things like learning the place on foot, shopping and eating locally, and getting to know your neighbors. I am bad about integrating into a new community every time we move, so I picked up some good tips. Warnick uses examples from all over (though mostly U.S. locations), but also makes it specific to her home of Blacksburg, Virginia.

“A cabinet of fantasies, a source of knowledge, a collection of lore from past and present, a place to dream… A bookshop can be so many things.” In A Very Special Year by Thomas Montasser, Valerie takes over Ringelnatz & Co. bookshop when the owner, her Aunt Charlotte, disappears. She has the entrepreneurial skills to run a business and gradually develops a love of books, too. The title book is a magical tome with blank pages that reveal the reader’s destination when the time is right. Twee but enjoyable; a quick read.

“A cabinet of fantasies, a source of knowledge, a collection of lore from past and present, a place to dream… A bookshop can be so many things.” In A Very Special Year by Thomas Montasser, Valerie takes over Ringelnatz & Co. bookshop when the owner, her Aunt Charlotte, disappears. She has the entrepreneurial skills to run a business and gradually develops a love of books, too. The title book is a magical tome with blank pages that reveal the reader’s destination when the time is right. Twee but enjoyable; a quick read.

Eleven Hours by Pamela Erens is a taut thriller set during one woman’s experience of childbirth in New York City in 2004. Flashbacks to how the patient and her Caribbean nurse got where they are now add emotional depth. Another very quick read.

Eleven Hours by Pamela Erens is a taut thriller set during one woman’s experience of childbirth in New York City in 2004. Flashbacks to how the patient and her Caribbean nurse got where they are now add emotional depth. Another very quick read.

Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig is a psychologically astute novella in which a 12-year-old tries to interpret what’s happening between his mother and a fellow hotel guest, a baron he looks up to. For this naïve boy, many things come as a shock, including the threat of sex and the possibility of deception. This reminded me most of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. (On a hill above Salzburg we discovered a strange disembodied bust of Stefan Zweig, along with a plaque and a road sign.)

Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig is a psychologically astute novella in which a 12-year-old tries to interpret what’s happening between his mother and a fellow hotel guest, a baron he looks up to. For this naïve boy, many things come as a shock, including the threat of sex and the possibility of deception. This reminded me most of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. (On a hill above Salzburg we discovered a strange disembodied bust of Stefan Zweig, along with a plaque and a road sign.)

Playing Dead by Elizabeth Greenwood (releases August 9th) was great fun. Thinking of the six-figure education debt weighing on her shoulders, she surveys various cases of people who faked their own death or simply tried to disappear. Death fraud/“pseudocide” is not as easy to get away with as you might think. Fake drownings are especially suspect. I found most ironic the case of a man who lived successfully for 20 years under an assumed name but was caught when police stopped him for having a license plate light out. I particularly liked the chapter in which Greenwood travels to the Philippines, a great place to fake your death, and comes back with a copy of her own death certificate.

Playing Dead by Elizabeth Greenwood (releases August 9th) was great fun. Thinking of the six-figure education debt weighing on her shoulders, she surveys various cases of people who faked their own death or simply tried to disappear. Death fraud/“pseudocide” is not as easy to get away with as you might think. Fake drownings are especially suspect. I found most ironic the case of a man who lived successfully for 20 years under an assumed name but was caught when police stopped him for having a license plate light out. I particularly liked the chapter in which Greenwood travels to the Philippines, a great place to fake your death, and comes back with a copy of her own death certificate.

Miss Jane by Brad Watson (releases July 12th) is a historical novel loosely based on the story of the author’s great-aunt. Born in Mississippi in 1915, she had malformed genitals, which led to lifelong incontinence. Jane is a wonderfully plucky protagonist, and her friendship with her doctor, Ed Thompson, is particularly touching. “You would not think someone so afflicted would or could be cheerful, not prone to melancholy or the miseries.” This reminded me most of What Is Visible by Kimberly Elkins, an excellent novel about living a full life and finding romance in spite of disability.

Miss Jane by Brad Watson (releases July 12th) is a historical novel loosely based on the story of the author’s great-aunt. Born in Mississippi in 1915, she had malformed genitals, which led to lifelong incontinence. Jane is a wonderfully plucky protagonist, and her friendship with her doctor, Ed Thompson, is particularly touching. “You would not think someone so afflicted would or could be cheerful, not prone to melancholy or the miseries.” This reminded me most of What Is Visible by Kimberly Elkins, an excellent novel about living a full life and finding romance in spite of disability.

I also left two novels unfinished (that’ll be for another post) and made progress in two other nonfiction titles. All in all, a great set of reading!

I’m supposed to be making my way through just the books we already own for the rest of the summer, but when I got back of course I couldn’t resist volunteering for a few new books available through Nudge and The Bookbag. Apart from a few blog reviews I’m bound to, my summer plan will be to give the occasional quick roundup of what I’ve read of late.

What have you been reading recently?

European Holiday Reading – A (Temporary) Farewell

Tomorrow we’re off to continental Europe for two weeks of train travel, making stops in Brussels, Freiburg (Germany), two towns in Switzerland, and Salzburg and Vienna in Austria. This will be some of the most extensive travel I’ve done in Europe in the 11 or so years that I’ve lived here – and the first time I’ve been to Switzerland or Austria – so I’m excited. I’ve been working like a fiend recently to catch up and/or get ahead on reviews and blogs, so it will be particularly good to spend two weeks away from a computer. It’s also nice that our adventure doesn’t have to start with going to an airport.

Here’s what I’ve packed:

- Setting Free the Bears by John Irving (his first novel; set in Vienna)

- Diary of a Pilgrimage by Jerome K. Jerome (about a train journey from England to Germany)

- Me and Kaminski by Daniel Kehlmann (the author is Austrian)

- A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler (a novella set in the Austrian Alps)

+ Enchanting Alpine Flowers & the Rough Guide to Vienna

Also on the e-readers, downloaded from Project Gutenberg:

- Three Men on the Bummel by Jerome K. Jerome (further humorous antics in Germany)

- Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig (a novella; the author is Austrian)

+ another 250+ Kindle books from a wide variety of genres and topics – I’ll certainly have no shortage of reading material!

(Looking back now, it occurs to me that this all skews rather towards Austria! Oh well. Vienna is one of our longer stops.)

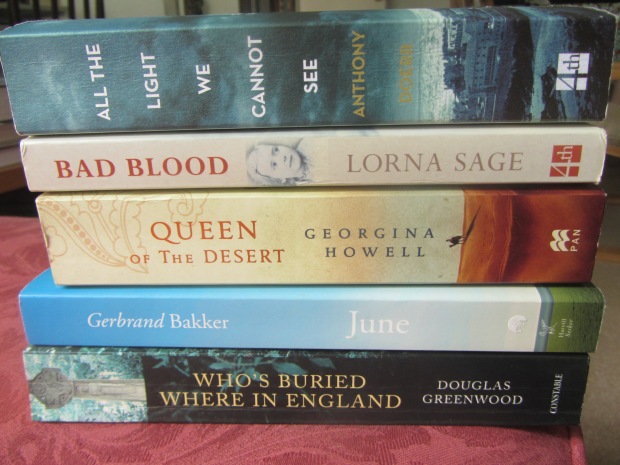

I’m supposed to be making my way through the books we already own, but on Saturday I was overcome with temptation at our local charity shop when I saw that all paperbacks were on sale – 5 for £1. I’m in the middle of one of the novels I bought that day, June by Gerbrand Bakker, along with The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler, and need to decide whether to put them on hold while I’m away or take one or both with me. Either way I’ll try to finish June this month; it’s just too appropriate not to!

I was also overcome with temptation at the thought of a new Eowyn Ivey novel coming out in August, so requested a copy for review.

It’s an odd time here in the UK. Readers from North America or elsewhere might be unaware that we’re gearing up for a referendum to decide whether to remain in the European Union. By the time we pass back through Brussels (‘capital’ of the European Union) on the 24th, there’s every chance the UK might no longer be an official member of Europe. I haven’t taken British citizenship so am ineligible to cast a vote; I won’t court debate by elaborating on a comparison of “Brexit” with the specter of Trump in the States. My husband has sent in his postal vote, so collectively we’ve done all we can do and now just have to wait and see.

We’re not back until late on the 24th, but I’ve scheduled a few posts for while we’re away. I will only have sporadic Internet access during these weeks, so won’t be replying to blog comments or reading fellow bloggers’ posts, but I promise to catch up when we get back.

Happy June reading!

Philip Rhayader is a lonely bird artist on the Essex marshes by an abandoned lighthouse. “His body was warped, but his heart was filled with love for wild and hunted things. He was ugly to look upon, but he created great beauty.” One day a little girl, Fritha, brings him an injured snow goose and he puts a splint on its wing. The recovered bird becomes a friend to them both, coming back each year to spend time at Philip’s makeshift bird sanctuary. As Fritha grows into a young woman, she and Philip fall in love (slightly creepy), only for him to leave to help with the evacuation of Dunkirk. This is a melancholy and in some ways predictable little story. It was originally published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1940 and became a book the following year. I read a lovely version illustrated by Angela Barrett. It’s the second of Gallico’s animal fables I’ve read; I slightly preferred

Philip Rhayader is a lonely bird artist on the Essex marshes by an abandoned lighthouse. “His body was warped, but his heart was filled with love for wild and hunted things. He was ugly to look upon, but he created great beauty.” One day a little girl, Fritha, brings him an injured snow goose and he puts a splint on its wing. The recovered bird becomes a friend to them both, coming back each year to spend time at Philip’s makeshift bird sanctuary. As Fritha grows into a young woman, she and Philip fall in love (slightly creepy), only for him to leave to help with the evacuation of Dunkirk. This is a melancholy and in some ways predictable little story. It was originally published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1940 and became a book the following year. I read a lovely version illustrated by Angela Barrett. It’s the second of Gallico’s animal fables I’ve read; I slightly preferred

“A Search for the World’s Purest, Deepest Snowfall” reads the subtitle on the cover. English set out from his home in London for two years of off-and-on travel in snowy places, everywhere from Greenland to Washington State. In Jericho, Vermont, he learns about Wilson Bentley, an amateur scientist who was the first to document snowflake shapes through microscope photographs. In upstate New York, he’s nearly stranded during the Blizzard of 2006. He goes skiing in France and learns about the deadliest avalanches – Britain’s worst was in Lewes in 1836. In Scotland’s Cairngorms, he learns how those who work in the ski industry are preparing for the 60–80% reduction of snow predicted for this century. An appendix dubbed “A Snow Handbook” gives some technical information on how snow forms, what the different crystal shapes are called, and how to build an igloo, along with whimsical lists of 10 snow stories (I’ve read six), 10 snowy films, etc.

“A Search for the World’s Purest, Deepest Snowfall” reads the subtitle on the cover. English set out from his home in London for two years of off-and-on travel in snowy places, everywhere from Greenland to Washington State. In Jericho, Vermont, he learns about Wilson Bentley, an amateur scientist who was the first to document snowflake shapes through microscope photographs. In upstate New York, he’s nearly stranded during the Blizzard of 2006. He goes skiing in France and learns about the deadliest avalanches – Britain’s worst was in Lewes in 1836. In Scotland’s Cairngorms, he learns how those who work in the ski industry are preparing for the 60–80% reduction of snow predicted for this century. An appendix dubbed “A Snow Handbook” gives some technical information on how snow forms, what the different crystal shapes are called, and how to build an igloo, along with whimsical lists of 10 snow stories (I’ve read six), 10 snowy films, etc.

This has a very similar format and scope to The Snow Tourist, with Campbell ranging from Greenland and continental Europe to the USA in her search for the science and stories of ice. For English’s chapter on skiing, substitute a section on ice skating. I only skimmed this one because – in what I’m going to put down to a case of reader–writer mismatch – I started it three times between November 2018 and now and could never get further than page 60. See these reviews from

This has a very similar format and scope to The Snow Tourist, with Campbell ranging from Greenland and continental Europe to the USA in her search for the science and stories of ice. For English’s chapter on skiing, substitute a section on ice skating. I only skimmed this one because – in what I’m going to put down to a case of reader–writer mismatch – I started it three times between November 2018 and now and could never get further than page 60. See these reviews from  The travails of his long trial runs with the dogs – the sled flipping over, having to walk miles after losing control of the dogs, being sprayed in the face by multiple skunks – sound bad enough, but once the Iditarod begins the misery ramps up. The course is nearly 1200 miles, over 17 days. It’s impossible to stay warm or get enough food, and a lack of sleep leads to hallucinations. At one point he nearly goes through thin ice. At another he’s run down by a moose. He also watches in horror as a fellow contestant kicks a dog to death.

The travails of his long trial runs with the dogs – the sled flipping over, having to walk miles after losing control of the dogs, being sprayed in the face by multiple skunks – sound bad enough, but once the Iditarod begins the misery ramps up. The course is nearly 1200 miles, over 17 days. It’s impossible to stay warm or get enough food, and a lack of sleep leads to hallucinations. At one point he nearly goes through thin ice. At another he’s run down by a moose. He also watches in horror as a fellow contestant kicks a dog to death. Two nonfiction books entitled Wintering:

Two nonfiction books entitled Wintering: