Spring Reads, Part II: Blossomise, Spring Chicken & Cold Spring Harbor

Our garden is an unruly assortment of wildflowers, rosebushes, fruit trees and hedge plants, along with an in-progress pond, and we’ve made a few half-hearted attempts at planting vegetable seeds and flower bulbs. It felt more like summer earlier in May, before we left for France; as the rest of the spring plays out, we’ll see if the beetroot, courgettes, radishes and tomatoes amount to anything. The gladioli have certainly been shooting for the sky!

I recently encountered spring (if only in name) through these three books, a truly mixed bag: a novelty poetry book memorable more for the illustrations than for the words, a fascinating popular account of the science of ageing, and a typically depressing (if you know the author, anyway) novel about failing marriages and families. Part I of my Spring Reading was here.

Blossomise by Simon Armitage; illus. Angela Harding (2024)

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

A favourite passage: “Scented and powdered / she’s staging / a one-tree show / with hi-viz blossoms / and lip-gloss petals; / she’ll season the pavements / and polished stones / with something like snow.” (Public library) ![]()

Spring Chicken: Stay Young Forever (or Die Trying) by Bill Gifford (2015)

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Over the course of the book, Gifford meets all number of researchers and cranks as he attends conferences, travels to spend time with centenarians and scientists, and participates in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. There have been some truly zany ideas about how to pause or reverse aging, such as self-dosing with hormones (Suzanne Somers is one proponent), but long-term use is discouraged. Some things that do help, to an extent, are calorie restriction and periodic fasting plus, possibly, red wine, coffee and aspirin. But the basic advice is nothing we don’t already know about health: don’t eat too much and exercise, i.e., avoid obesity. The layman-interpreting-science approach reminded me of Mary Roach’s. There was some crossover in content with Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine and various books I’ve read about dementia. Fun and enlightening. (New purchase – bargain book from Dollar Tree, Bowie, MD) ![]()

Cold Spring Harbor by Richard Yates (1986)

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Evan and Rachel soon marry and agree to Gloria’s plan of sharing a house in Cold Spring Harbor, where the Shepards live (Evan’s mother is also an alcoholic, but less functional; she hides behind the “invalid” label). Take it from me: living with your in-laws is never a good idea! As the Second World War looms, and with Evan and Rachel expecting a baby, it’s clear something will have to give with this uneasy family arrangement, but the dramatic break I was expecting – along the lines of a death or accident – never arrived. Instead, there’s just additional slow crumbling, and the promise of greater suffering to come. Although Yates’s character portraits are as penetrating as in Easter Parade, I found the plot a little lacklustre here. (Secondhand – Clutterbooks, Sedbergh) ![]()

Any ‘spring’ reads for you recently?

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach (back to school in the Midwest)

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach (back to school in the Midwest) I’ll admit it: it was Angela Harding’s gorgeous cover illustration that drew me to this one. But I found a story that lived up to it, too. October, who has just turned 11 and is named after her birth month, lives in the woods with her father. Their shelter and their ways are fairly primitive, but it’s what October knows and loves. When her father has an accident and she’s forced into joining her mother’s London life, her only consolations are her rescued barn owl chick, Stig, and the mudlarking hobby she takes up with her new friend, Yusuf.

I’ll admit it: it was Angela Harding’s gorgeous cover illustration that drew me to this one. But I found a story that lived up to it, too. October, who has just turned 11 and is named after her birth month, lives in the woods with her father. Their shelter and their ways are fairly primitive, but it’s what October knows and loves. When her father has an accident and she’s forced into joining her mother’s London life, her only consolations are her rescued barn owl chick, Stig, and the mudlarking hobby she takes up with her new friend, Yusuf.

The second in the quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories. Autumn is a time for stocking the pantry shelves with preserves, so the mice are out gathering berries, fruit and mushrooms. Young Primrose wanders off, inadvertently causing alarm – though all she does is meet a pair of elderly harvest mice and stay for tea and cake in their round nest amid the cornstalks. I love all the little touches in the illustrations: the patchwork tea cosy matches the quilt on the bed one floor up, and nearly every page is adorned with flowers and other foliage. After we get past the mild peril that seems to be de rigueur for any children’s book, all is returned to a comforting normal. Time to get the Winter volume out from the library. (Public library)

The second in the quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories. Autumn is a time for stocking the pantry shelves with preserves, so the mice are out gathering berries, fruit and mushrooms. Young Primrose wanders off, inadvertently causing alarm – though all she does is meet a pair of elderly harvest mice and stay for tea and cake in their round nest amid the cornstalks. I love all the little touches in the illustrations: the patchwork tea cosy matches the quilt on the bed one floor up, and nearly every page is adorned with flowers and other foliage. After we get past the mild peril that seems to be de rigueur for any children’s book, all is returned to a comforting normal. Time to get the Winter volume out from the library. (Public library)  The first whole book I’ve read in French in many a year. I just about coped, given that it’s a picture book with not all that many words on a page; any vocabulary I didn’t know offhand, I could understand in context. It’s late into the autumn and Papa Bear is ready to start hibernating for the year, but Little Bear spies a late-flying bee and follows it out of the woods and all the way to the big city. Papa Bear, realizing his lad isn’t beside him in the cave, sets out in pursuit and bee, cub and bear all end up at the opera hall, to the great surprise of the audience. What will Papa do with his moment in the spotlight? This is a lovely book that, despite the whimsy, still teaches about the seasons and parent–child bonds as it offers a vision of how humans and animals could coexist. I’ve since found out that this was made into a series of four books, all available in English translation. (Little Free Library)

The first whole book I’ve read in French in many a year. I just about coped, given that it’s a picture book with not all that many words on a page; any vocabulary I didn’t know offhand, I could understand in context. It’s late into the autumn and Papa Bear is ready to start hibernating for the year, but Little Bear spies a late-flying bee and follows it out of the woods and all the way to the big city. Papa Bear, realizing his lad isn’t beside him in the cave, sets out in pursuit and bee, cub and bear all end up at the opera hall, to the great surprise of the audience. What will Papa do with his moment in the spotlight? This is a lovely book that, despite the whimsy, still teaches about the seasons and parent–child bonds as it offers a vision of how humans and animals could coexist. I’ve since found out that this was made into a series of four books, all available in English translation. (Little Free Library)  This YA graphic novel is set on a Nebraska pumpkin patch that’s more like Disney World than a simple field down the road. Josiah and Deja have worked together at the Succotash Hut for the last three autumns. Today they’re aware that it’s their final Halloween before leaving for college. Deja’s goal is to try every culinary delicacy the patch has to offer – a smorgasbord of foodstuffs that are likely to be utterly baffling to non-American readers: candy apples, Frito pie (even I hadn’t heard of this one), kettle corn, s’mores, and plenty of other saccharine confections.

This YA graphic novel is set on a Nebraska pumpkin patch that’s more like Disney World than a simple field down the road. Josiah and Deja have worked together at the Succotash Hut for the last three autumns. Today they’re aware that it’s their final Halloween before leaving for college. Deja’s goal is to try every culinary delicacy the patch has to offer – a smorgasbord of foodstuffs that are likely to be utterly baffling to non-American readers: candy apples, Frito pie (even I hadn’t heard of this one), kettle corn, s’mores, and plenty of other saccharine confections.

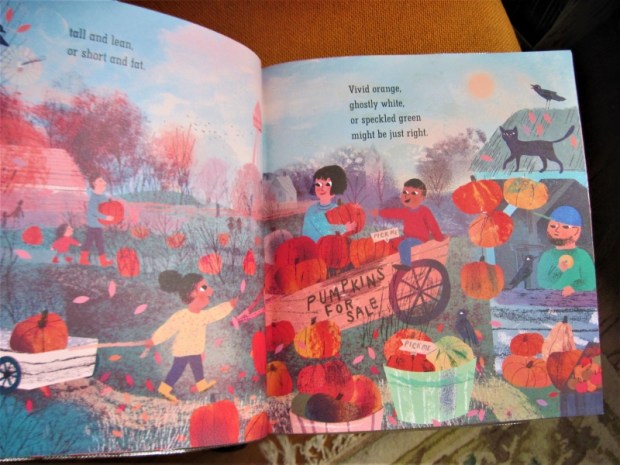

From picking the best pumpkin at the patch to going out trick-or-treating, this is a great introduction to Halloween traditions. It even gives step-by-step instructions for carving a jack-o’-lantern. The drawing style – generally 2D, and looking like it could be part cut paper collages, with some sponge painting – reminds me of Ezra Jack Keats and most of the characters are not white, which is refreshing. There are lots of little autumnal details to pick out in the two-page spreads, with a black cat and crows on most pages and a set of twins and a mouse on some others. The rhymes are either in couplets or ABCB patterns. Perfect October reading. (Public library)

From picking the best pumpkin at the patch to going out trick-or-treating, this is a great introduction to Halloween traditions. It even gives step-by-step instructions for carving a jack-o’-lantern. The drawing style – generally 2D, and looking like it could be part cut paper collages, with some sponge painting – reminds me of Ezra Jack Keats and most of the characters are not white, which is refreshing. There are lots of little autumnal details to pick out in the two-page spreads, with a black cat and crows on most pages and a set of twins and a mouse on some others. The rhymes are either in couplets or ABCB patterns. Perfect October reading. (Public library)  Any super-autumnal reading for you this year?

Any super-autumnal reading for you this year?  .

.

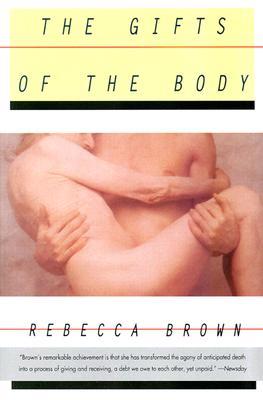

This is rather like a set of linked short stories, narrated by a home care aide who bathes and feeds those dying of AIDS. The same patients appear in multiple chapters titled “The Gift of…” (Sweat, Tears, Hunger, etc.) – Rick, Ed, Carlos, and Marty, with brief appearances from Mike and Keith. But for me the most poignant story was that of Connie Lindstrom, an old woman who got a dodgy blood transfusion after her mastectomy; the extra irony to her situation is that her son Joe is gay, and feels guilty because he thinks he should have been the one to get sick. Several characters move in and out of hospice care, and one building is so known for its AIDS victims that a savant resident greets the narrator with a roll call of its dead and dying. Brown herself had been a home-care worker, and she delivers these achingly sad vignettes in plain language that keeps the book from ever turning maudlin.

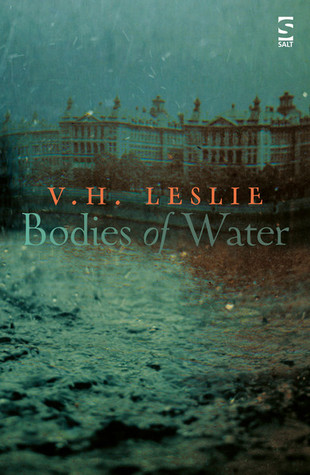

This is rather like a set of linked short stories, narrated by a home care aide who bathes and feeds those dying of AIDS. The same patients appear in multiple chapters titled “The Gift of…” (Sweat, Tears, Hunger, etc.) – Rick, Ed, Carlos, and Marty, with brief appearances from Mike and Keith. But for me the most poignant story was that of Connie Lindstrom, an old woman who got a dodgy blood transfusion after her mastectomy; the extra irony to her situation is that her son Joe is gay, and feels guilty because he thinks he should have been the one to get sick. Several characters move in and out of hospice care, and one building is so known for its AIDS victims that a savant resident greets the narrator with a roll call of its dead and dying. Brown herself had been a home-care worker, and she delivers these achingly sad vignettes in plain language that keeps the book from ever turning maudlin. Left over from my R.I.P. reading plans. This was nearly a one-sitting read for me: I read 94 pages in one go, though that may be because I was trapped under the cat. The first thing I noted was that the setup and dual timeframe are exactly the same as in Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered: we switch between the same place in 2016 and 1871. In this case it’s Wakewater House, a residential development by the Thames that incorporates the site of a dilapidated Victorian hydrotherapy center. After her partner cheats on her, Kirsten moves into Wakewater, where she’s alone apart from one neighbor, Manon, a hoarder who’s researching Anatomical Venuses – often modeled on prostitutes who drowned themselves in the river. In the historical strand, we see Wakewater through the eyes of Evelyn Byrne, who rescues street prostitutes and, after a disastrously ended relationship of her own, has arrived to take the Water Cure.

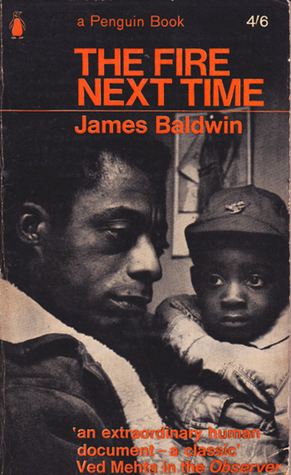

Left over from my R.I.P. reading plans. This was nearly a one-sitting read for me: I read 94 pages in one go, though that may be because I was trapped under the cat. The first thing I noted was that the setup and dual timeframe are exactly the same as in Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered: we switch between the same place in 2016 and 1871. In this case it’s Wakewater House, a residential development by the Thames that incorporates the site of a dilapidated Victorian hydrotherapy center. After her partner cheats on her, Kirsten moves into Wakewater, where she’s alone apart from one neighbor, Manon, a hoarder who’s researching Anatomical Venuses – often modeled on prostitutes who drowned themselves in the river. In the historical strand, we see Wakewater through the eyes of Evelyn Byrne, who rescues street prostitutes and, after a disastrously ended relationship of her own, has arrived to take the Water Cure. This was written yesterday, right? Actually, it was 55 years ago, but apart from the use of the word “Negro” you might have fooled me. Baldwin’s writing is still completely relevant, and eminently quotable. I can’t believe I hadn’t read him until now. This hard-hitting little book is composed of two essays that first appeared elsewhere. The first, “My Dungeon Shook,” a very short piece from the Madison, Wisconsin Progressive, is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation. No doubt it directly inspired Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me.

This was written yesterday, right? Actually, it was 55 years ago, but apart from the use of the word “Negro” you might have fooled me. Baldwin’s writing is still completely relevant, and eminently quotable. I can’t believe I hadn’t read him until now. This hard-hitting little book is composed of two essays that first appeared elsewhere. The first, “My Dungeon Shook,” a very short piece from the Madison, Wisconsin Progressive, is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation. No doubt it directly inspired Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. How to See Nature (1940), a quaint and perhaps slightly patronizing book by Shropshire naturalist and photographer Frances Pitt, was intended to help city evacuees cope with life in the countryside. Recently Pitt’s publisher, Batsford, commissioned Shropshire naturalist Paul Evans to revisit the topic. The result is a simply lovely volume (with a cover illustration by Angela Harding and black-and-white interior drawings by Evans’s partner, Maria Nunzia) that reflects on the range of modern relationships with nature and revels in the wealth of wildlife and semi-wild places we still have in Britain.

How to See Nature (1940), a quaint and perhaps slightly patronizing book by Shropshire naturalist and photographer Frances Pitt, was intended to help city evacuees cope with life in the countryside. Recently Pitt’s publisher, Batsford, commissioned Shropshire naturalist Paul Evans to revisit the topic. The result is a simply lovely volume (with a cover illustration by Angela Harding and black-and-white interior drawings by Evans’s partner, Maria Nunzia) that reflects on the range of modern relationships with nature and revels in the wealth of wildlife and semi-wild places we still have in Britain. Throughout, Evans treats issues like tree blight, climate change and species persecution with a light touch. Although it’s clear he’s aware of the diminished state of nature and quietly irate at how we are all responsible for pollution and invasive species, he writes lovingly and with poetic grace. I would not hesitate to recommend this to fans of contemporary nature writing.

Throughout, Evans treats issues like tree blight, climate change and species persecution with a light touch. Although it’s clear he’s aware of the diminished state of nature and quietly irate at how we are all responsible for pollution and invasive species, he writes lovingly and with poetic grace. I would not hesitate to recommend this to fans of contemporary nature writing.