Blog Tour: Literary Landscapes, edited by John Sutherland

The sense of place can be a major factor in a book’s success – did you know there is a whole literary prize devoted to just this? (The Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize, “for a distinguished work of fiction, non-fiction or poetry, evoking the spirit of a place.”) No matter when or where a story is set, an author can bring it to life through authentic details that appeal to all the senses, making you feel like you’re on Prince Edward Island or in the Gaudarrama Mountains even if you’ve never visited Atlantic Canada or central Spain. The 75 essays of Literary Landscapes, a follow-up volume to 2016’s celebrated Literary Wonderlands, illuminate the real-life settings of fiction from Jane Austen’s time to today. Maps, author and cover images, period and modern photographs, and other full-color illustrations abound.

The sense of place can be a major factor in a book’s success – did you know there is a whole literary prize devoted to just this? (The Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize, “for a distinguished work of fiction, non-fiction or poetry, evoking the spirit of a place.”) No matter when or where a story is set, an author can bring it to life through authentic details that appeal to all the senses, making you feel like you’re on Prince Edward Island or in the Gaudarrama Mountains even if you’ve never visited Atlantic Canada or central Spain. The 75 essays of Literary Landscapes, a follow-up volume to 2016’s celebrated Literary Wonderlands, illuminate the real-life settings of fiction from Jane Austen’s time to today. Maps, author and cover images, period and modern photographs, and other full-color illustrations abound.

Each essay serves as a compact introduction to a literary work, incorporating biographical information about the author, useful background and context on the book’s publication, and observations on the geographical location as it is presented in the story – often through a set of direct quotations. (Because each work is considered as a whole, you may come across spoilers, so keep that in mind before you set out to read an essay about a classic you haven’t read but still intend to.) The authors profiled range from Mark Twain to Yukio Mishima and from Willa Cather to Elena Ferrante. A few of the world’s great cities appear in multiple essays, though New York City as variously depicted by Edith Wharton, Jay McInerney and Francis Spufford is so different as to be almost unrecognizable as the same place.

One of my favorite pieces is on Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. “Dickens was not interested in writing a literary tourist’s guide,” it explains; “He was using the city as a metaphor for how the human condition could, unattended, go wrong.” I also particularly enjoyed those on Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped. The fact that I used to live in Woking gave me a special appreciation for the essay on H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, “a novel that takes the known landscape and, brilliantly, estranges it.” The two novels I’ve been most inspired to read are Thomas Wharton’s Icefields (1995; set in Jasper, Alberta) and Kate Grenville’s The Secret River (2005; set in New South Wales).

The essays vary subtly in terms of length and depth, with some focusing on plot and themes and others thinking more about the author’s experiences and geographical referents. They were contributed by academics, writers and critics, some of whom were familiar names for me – including Nicholas Lezard, Robert Macfarlane, Laura Miller, Tim Parks and Adam Roberts. My main gripe about the book would be that the individual essays have no bylines, so to find out who wrote a certain one you have to flick to the back and skim through all the contributor biographies until you spot the book in question. There are also a few more typos than I tend to expect from a finished book from a traditional press (e.g. “Lady Deadlock” in the Bleak House essay!). Still, it is a beautifully produced, richly informative tome that should make it onto many a Christmas wish list this year; it would make an especially suitable gift for a young person heading off to study English at university. It’s one to have for reference and dip into when you want to be inspired to discover a new place via an armchair visit.

Literary Landscapes will be published by Modern Books on Thursday, October 25th. My thanks to Alison Menzies for arranging my free copy for review.

Blog Tour Review: The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon

The Incendiaries is a sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Will Kendall left his California Bible college when he lost his faith. Soon after transferring to Edwards in upstate New York, he falls for Phoebe Lin at a party. Although he’s working in a restaurant to pay his way, he hides his working-class background to fit in with Phoebe and her glitzy, careless friends. Phoebe is a failed piano prodigy who can’t forgive herself: her mother died in a car Phoebe was driving. John Leal, a half-Korean alumnus, worked with refugees in China and was imprisoned in North Korea. Now he’s started a vaguely Christian movement called Jejah (Korean for “disciple”) that involves forced baptisms, intense confessions and self-flagellation. It’s no coincidence his last name rhymes with zeal.

The Incendiaries is a sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Will Kendall left his California Bible college when he lost his faith. Soon after transferring to Edwards in upstate New York, he falls for Phoebe Lin at a party. Although he’s working in a restaurant to pay his way, he hides his working-class background to fit in with Phoebe and her glitzy, careless friends. Phoebe is a failed piano prodigy who can’t forgive herself: her mother died in a car Phoebe was driving. John Leal, a half-Korean alumnus, worked with refugees in China and was imprisoned in North Korea. Now he’s started a vaguely Christian movement called Jejah (Korean for “disciple”) that involves forced baptisms, intense confessions and self-flagellation. It’s no coincidence his last name rhymes with zeal.

Much of the book is filtered through Will’s perspective; even sections headed “Phoebe” and “John Leal” most often contain his second-hand recounting of Phoebe’s words, or his imagined rendering of Leal’s thoughts – bizarre and fervent. Only in a few spots is it clear that the “I” speaking is actually Phoebe. This plus a lack of speech marks makes for a somewhat disorienting reading experience, but that is very much the point. Will and Phoebe’s voices and personalities start to merge until you have to shake your head for some clarity. The irony that emerges is that Phoebe is taking the opposite route to Will’s: she is drifting from faithless apathy into radical religion, drawn in by Jejah’s promise of atonement.

As in Celeste Ng’s novels, we know from the very start the climactic event that powers the whole book: the members of Jejah set off a series of bombs at abortion clinics, killing five. The mystery, then, is not so much what happened but why. In particular, we’re left to question how Phoebe could be transformed so quickly from a vapid party girl to a religious extremist willing to suffer for her beliefs.

Kwon spent 10 years writing this book, and that time and diligence come through in how carefully honed the prose is: such precise images; not a single excess word. I can see how some might find the style frustratingly oblique, but for me it was razor sharp, and the compelling religious theme was right up my street. It’s a troubling book, one that keeps tugging at your elbow. Recommended to readers of Sweetbitter and Shelter.

Favorite lines:

“This has been the cardinal fiction of my life, its ruling principle: if I work hard enough, I’ll get what I want.”

“People with no experience of God tend to think that leaving the faith would be a liberation, a flight from guilt, rules, but what I couldn’t forget was the joy I’d known, loving Him.”

My rating:

The Incendiaries will be published by Virago Press on September 6th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Note: An excerpt from The Incendiaries appeared in The Best Small Fictions 2016 (ed. Stuart Dybek), which I reviewed for Small Press Book Review. I was interested to look back and see that, at that point, her work in progress was entitled Heroics.

I was delighted to be invited to participate in the blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews are appearing today.

Blog Tour: Extract from The Power of Dog by Andrew G. Marshall

Last April I participated in the blog tour for Andrew G. Marshall’s previous book, My Mourning Year, a memoir about the death of his partner Thom and his journey through grief.

Last April I participated in the blog tour for Andrew G. Marshall’s previous book, My Mourning Year, a memoir about the death of his partner Thom and his journey through grief.

The Power of Dog is like a sequel; it tells what happened when Andrew acquired a collie cross puppy named Flash.

Alas, a copy didn’t arrive in time for me to read it before I left for America, but to open up the blog tour today I have an extract for you, and I look forward to reading the book when I get back.

Prologue

What I wanted most and what frightened me most, when I was a child, turned out to be the same thing. Every year as I blew out my birthday cake candles, I’d wish for a puppy ‒ with my eyes tightly closed to maximise the magic. But while my daydreams were full of adoring Labradors fetching sticks, my nightmares were stalked by their distant relatives: wolves.

My parents belonged to the ‘comfortably off’ middle classes and were only too happy to pay for tennis lessons, new bikes and summer camp – indeed they were particularly keen to send me to these. My birthday cake was always home baked, a fruit cake decorated with teddy bears sitting in a spiky snow scene. Despite the growing number of candles and my entreaties, the gods of birthday wishes were unmoved. Although my mother agreed first to guinea pigs and later mice, she remained firm about getting a dog: ‘I’ll be the one who ends up walking it.’

I can pinpoint the exact moment the nightmares started. Our next-door neighbours, whom I’d christened H’auntie and H’uncle, had retired to Bournemouth and one summer we stayed overnight at their house. I must have been four or five and already possessed a vivid imagination. In the middle of the night, I had to tiptoe across an unfamiliar landing to the lavatory ‒ never toilet because my mother considered the term vulgar. Returning, I closed the bedroom door as quietly as possible and revealed a large hairy wolf ready to pounce. I can’t remember if I screamed or whether anybody came. Maybe my mother pointed out that the wolf was really a man’s woollen winter dressing gown hanging on a hook; all of those details have been forgotten but I can still remember the nightmares.

Back home in Northampton, I slept in a tall wooden bed which had originally belonged to my father. The mattress and the springs were so old that they had sunk to form a hollow which fitted exactly around my small body. I felt safe nestling between the two hills on either side. However, the old-fashioned design left a large amount of space under the bed. By day, this space housed a box of favourite toys, but at night I never had the nerve to lift the white candlewick counterpane. I instinctively knew the wolves had set up camp there. The rules of engagement were simple: I was safe in bed, but they could pounce and catch me if I didn’t run fast enough back from the loo ‒ an acceptable abbreviation. On particularly dark nights, the wolves would emerge from their lair and dance round the room with their teeth glinting in the moonlight. I’d scream out and Mummy would come and reassure me:

‘The wolves will not get you.’

She would lift the counterpane and show me.

‘There’s nothing there.’

It was easy for her to say – the wolves would disappear as soon as she’d open my bedroom door. But after she’d told me to ‘sleep tight’ and gone back to bed, they would rematerialise, slink back into the lair and an uneasy truce would be established.

Wolves did not have a monopoly on my fears. For a while in the sixties a ‘cop killer’ called Harry Roberts evaded the police by haunting my nightmares. If there was a strange-looking man drinking alone at the rugby club bar ‒ where my father was treasurer ‒ I would sidle up to one of my parents and whisper: ‘THERE’S HARRY ROBERTS.’ It must have been embarrassing for my parents, but in defence of my seven-year-old self, the rugby club did attract an odd crowd.

Fortunately, my fear of Harry Roberts was easy to cure. One night in 1966, I was allowed to stay up late to watch his capture on the news. I can still picture the small makeshift camp in the woods ‒ the blanket strung between three trees and the discarded tin cans ‒ but not where (except it was many miles from my home). I slept soundly that night.

Flushed by her success with Harry Roberts, my mother took me to London Zoo. I was softened up with lions, monkeys and possibly even a ride on an elephant. Next, she casually mentioned that they had wolves too. I can’t remember what I was wearing but I can picture myself in an anorak so large it came down past my knees ‒ ‘you’ll grow into it’ – being taken to an enclosure hidden in some back alley of the Zoo. Did I actually look at the wolves? Perhaps I refused. Perhaps they were asleep in their den. Whatever happened next, the pack under my bed would not be exorcised so easily.

At that age it was impossible to believe I would ever reach ten; but I did. I even turned eighteen and left home for university where I studied Politics and Sociology. After graduating, I got a job first at BRMB Radio in Birmingham (in the newsroom) and then Essex Radio in Southend (as a presenter and producer) and Radio Mercury in Crawley (where I rose to become Deputy Programme Controller). My nightmares about wolves had long since ended, but if they appeared on TV they would still make me feel uneasy and I would switch channels. I still wanted a dog, but I was far too practical. I had a career to pursue. Who would walk the dog? Would it be fair to leave it alone while I worked? I couldn’t be tied down by such responsibilities.

At thirty, I fell in love with Thom and we talked about getting a dog together. However, for the first four and a half years, he lived in Germany and I lived in Hurstpierpoint (a small Sussex village). In the spring of 1995, Thom finally moved over to England with plans to set up an interior design company. However, six months later, he fell ill. All our plans for dog-owning were put on hold, while we concentrated on getting him better. He spent months in hospital first in England and then in Germany and I spent a lot of time flying backwards and forwards between the two countries. I loved Thom with a passion that sometimes terrified me, so when he died, on 9 March 1997, I was completely inconsolable.

I moved into the office he’d created in our spare room, but I couldn’t stop the computer from still sending faxes from Andrew Marshall and Thom Hartwig. As far as Microsoft Word was concerned, he was immortal. I tried various strategies to cope with my bereavement but three different counsellors did not shift it. Two short-term relationships made me feel worse not better. I had just turned forty. My regular sources of income – being Agony Uncle for Live TV and writing a column for the Independent newspaper – were both terminated. My grief was further isolating me and many of Thom’s and my couple friendships had just withered away.

Approaching the Millennium, something had to change, but what?

The Power of Dog will be released by RedDoor Publishing on Thursday, July 12th. My thanks to the publisher for a review copy.

Blog Tour: Extract from Song by Michelle Jana Chan

Song escapes the poverty and natural disasters of his hometown in China by sailing to Guiana. The village medicine man describes Guiana as a kind of paradise, and tells him he can earn free passage if he presents himself to the Englishmen in Guangzhou. What he doesn’t realize is that he will effectively be an indentured servant, working in the sugarcane fields for years just to pay for the voyage. From Singapore to India to Guiana, it’s a long and fraught journey, and though his new home does dazzle with its colors and wildlife, it’s not the idyll he expected. Still, Song is determined to make something of himself. “He would yet live a life that was a story worth telling.”

Song escapes the poverty and natural disasters of his hometown in China by sailing to Guiana. The village medicine man describes Guiana as a kind of paradise, and tells him he can earn free passage if he presents himself to the Englishmen in Guangzhou. What he doesn’t realize is that he will effectively be an indentured servant, working in the sugarcane fields for years just to pay for the voyage. From Singapore to India to Guiana, it’s a long and fraught journey, and though his new home does dazzle with its colors and wildlife, it’s not the idyll he expected. Still, Song is determined to make something of himself. “He would yet live a life that was a story worth telling.”

I have an extract from Chapter 1, about the flooding in China, to whet your appetite:

Lishui Village, China, 1878

At first they were glad the rains came early. They had already finished their planting and the seedlings were beginning to push through. The men and women of Lishui straightened their backs, buckled from years of labouring, led the buffalo away and waited for the fields to turn green. With such early rains there might be three rice harvests if the weather continued to be clement. But they quickly lost hope of that. The sun did not emerge to bronze the crop. Instead the clouds hung heavy. More rain beat down upon an already sodden earth and lakes were born where even the old people said they could not remember seeing standing water.

The Li rose higher and higher. Every morning the men of the village walked to the river to watch the water lap at its banks like flames. Sometimes they stood there for hours, their faces as grey as the flat slate light. Still the rain fell, yet no one cared about their clothes becoming wet or the nagging coughs the chill brought on. Occasionally a man lifted his arm to wipe his face. But mostly they stood still like figures in a painting, staring upstream, watching the water barrel down, bulging under its own mass.

Before the end of the week the Li had spilled over its banks. A few days later the water had covered the footpaths and cart tracks, spreading like a tide across the land and sweeping away all the fine shoots of newly planted rice. Further upstream the river broke up carts, bamboo bridges and outbuildings; it knocked over vats of clean water and seeped beneath the doors of homes. Carried on its swirling currents were splintered planks of wood, rotting food, and shreds of sacking and rattan.

Song awoke to feel the straw mat wet beneath him. He reached out his hand. The water was gently rising and ebbing as if it was breathing. His brother Xiao Bo was crying in his sleep. The little boy had rolled off his mat and was lying curled up in the water. He was hugging his knees as if to stop himself from floating away.

Song’s father was not home yet. He and the other men had been working through the night trying to raise walls of mud and rein back the river’s strength. But the earthen barriers washed away even as they built them; they could only watch, hunched over their shovels.

The men did not return that day. As the hours passed the women grew anxious. They stopped by each other’s homes, asking for news, but nobody had anything to say. Song’s mother Zhang Je was short with the children. The little ones whimpered, sensing something was wrong.

Song huddled low with his sisters and brothers around the smoking fire which sizzled and spat but gave off no heat. They had wedged among the firewood an iron bowl but the rice inside was not warming. That was all they had left to eat now. Xiao Wan curled up closer to Song. His little brother followed him everywhere nowadays. His sisters Xiao Mei and San San sat opposite him, adding wet wood to the fire and poking at the ash with a stick. His mother stood in the doorway, the silhouette of Xiao Bo strapped to her back and her large rounded stomach tight with child.

The children dipped their hands into the bowl, squeezing grains of rice together, careful not to take more than their share. Song was trying to feed Xiao Wan but he was too weak even to swallow. The little boy closed his eyes and rested his head in Song’s lap, wheezing with each breath. Their mother continued to look out towards the fields, waiting, with Xiao Bo’s head slumped unnaturally to the side as he slept.

‘I don’t think they’re coming back.’

Song could barely hear what his mother was saying.

‘They’re too late,’ she muttered.

Song wasn’t sure if she was talking to him. ‘Mama?’

Her voice was more brisk. ‘They’re not coming back, I said.’

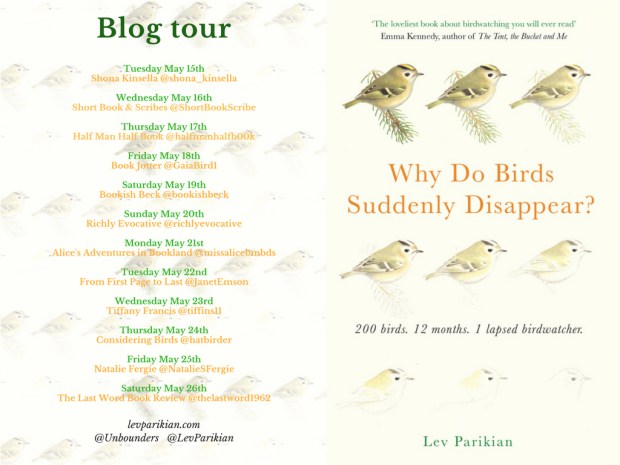

Blog Tour Review: Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? by Lev Parikian

Lev Parikian was a keen birdwatcher when he was 11, but as an adult he barely remembered most of what he used to know about birds. He’d confidently declare that he’d seen a nightingale and then be too embarrassed to later admit it was actually a skylark. Also, he had to acknowledge that he hadn’t been completely honest as a preteen birder: No way had he seen a black redstart, for instance. Probably about 30% of his childhood sightings could be dismissed as cheats or downright lies. As the birdwatching bug bit again at the start of 2016, he decided it was time to set the record straight. His aim? To see 200 birds in a year, with no twitching (driving many miles to see a reported rarity) and no cheating.

Lev Parikian was a keen birdwatcher when he was 11, but as an adult he barely remembered most of what he used to know about birds. He’d confidently declare that he’d seen a nightingale and then be too embarrassed to later admit it was actually a skylark. Also, he had to acknowledge that he hadn’t been completely honest as a preteen birder: No way had he seen a black redstart, for instance. Probably about 30% of his childhood sightings could be dismissed as cheats or downright lies. As the birdwatching bug bit again at the start of 2016, he decided it was time to set the record straight. His aim? To see 200 birds in a year, with no twitching (driving many miles to see a reported rarity) and no cheating.

Most of the book is a chronological tour through 2016, with each month’s new sightings totaled up at the end of the chapter. Being based in London isn’t the handicap one might expect – there’s a huge population of parakeets there nowadays, and the London Wetland Centre in Barnes is great for water birds – but Parikian also fills in his list through various trips around the country. He picks up red kites while in Windsor for a family wedding, and his list balloons in April thanks to trips to Minsmere and Rainham Marshes, where he finds additions like bittern and marsh harrier. The Isle of Wight, Scotland, Lindsifarne, North Norfolk… The months pass and the numbers mount until it’s the middle of December and his total is hovering at 196. Will he make it? I wouldn’t dare spoil the result for you!

I’ve always enjoyed ‘year-challenge’ books, everything from Julie Powell’s Julie and Julia to Nina Sankovitch’s Tolstoy and the Purple Chair, so I liked this memoir’s air of self-imposed competition, and its sense of humor. Having accompanied my husband on plenty of birdwatching trips, I could relate to the alternating feelings of elation and frustration. I also enjoyed the mentions of Parikian’s family history and career as a freelance conductor – I’d like to read more about this in his first book, Waving, Not Drowning (2013). This is one for fans of Alexandra Heminsley’s Leap In and Kyo Maclear’s Birds Art Life, or for anyone who needs reassurance that it’s never too late to pick up a new skill or return to a beloved hobby.

Lastly, I must mention what a beautiful physical object this book is. The good folk of Unbound have done it again. The cover image and endpapers reproduce Alan Harris’s lovely sketch of a gradually disappearing goldcrest, and if you lift the dustjacket you’re rewarded with the sight of some cheeky bird footprints traipsing across the cover.

Some favorite passages:

“Birders love a list. Day lists, week lists, month lists, year lists, life lists, garden lists, county lists, walk-to-work lists, seen-from-the-train lists, glimpsed-out-of-the-bathroom-window-while-doing-a-poo lists.”

“It’s one thing sitting in your favourite armchair, musing on the plumage differences between first- and second-winter black-headed gulls, but that doesn’t help identify the scrubby little blighter that’s just jigged into that bush, never to be seen again. And it’s no use asking them politely to damn well sit still blast you while I jot down the distinguishing features of your plumage in this notebook dammit which pocket is it in now where did I put the pencil ah here it is oh bugger it’s gone. They just won’t. Most disobliging.”

“There is a word in Swedish, gökotta, for the act of getting up early to listen to birdsong, but the knowledge that this word exists, while heartwarming, doesn’t make it any easier. It’s a bitter pill, this early rising, but my enthusiasm propels me to acts of previously unimagined heroism, and I set the alarm for an optimistic 5 a.m., before reality prompts me to change it to 5.15, no 5.30, OK then 5.45.”

My rating:

Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? was published by Unbound on May 17th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

I was delighted to be invited to participate in the blog tour for Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon (including on my hubby’s blog on Thursday!).

Blog Tour: Mr Peacock’s Possessions by Lydia Syson

Mr Peacock’s Possessions, Lydia Syson’s first novel for adults, will be published in the UK by Zaffre on May 17th. You might think of it as a cross between Lloyd Jones’s Mister Pip and Lucy Treloar’s Salt Creek. Set in the late 1870s in New Zealand and Oceania, it’s the story of the Peacock family, who settled on Monday Island two years ago, believing it would be their own “piece of paradise.” Mr Peacock is a self-assured man of many schemes. One day fifteen-year-old Lizzie spots a ship, and a Pacific Islander jumps off it and swims ashore. This is Kalala, who learned English and gentlemanly manners from “Mr Reverend” and narrates his chapters in a charming patois. He’s here to help with manual labour, but Mr Peacock unsettles him: “he goes from light to dark like a forest walk,” as his family knows all too well. The novel is based loosely on Syson’s husband’s family history.

Mr Peacock’s Possessions, Lydia Syson’s first novel for adults, will be published in the UK by Zaffre on May 17th. You might think of it as a cross between Lloyd Jones’s Mister Pip and Lucy Treloar’s Salt Creek. Set in the late 1870s in New Zealand and Oceania, it’s the story of the Peacock family, who settled on Monday Island two years ago, believing it would be their own “piece of paradise.” Mr Peacock is a self-assured man of many schemes. One day fifteen-year-old Lizzie spots a ship, and a Pacific Islander jumps off it and swims ashore. This is Kalala, who learned English and gentlemanly manners from “Mr Reverend” and narrates his chapters in a charming patois. He’s here to help with manual labour, but Mr Peacock unsettles him: “he goes from light to dark like a forest walk,” as his family knows all too well. The novel is based loosely on Syson’s husband’s family history.

Today as part of the blog tour I have an extract from Kalala’s narration as he approaches the island.

In water once more, all my limbs are joyful, and my ears too, joyful with bubbling whoosh, all sluice and surge and flow, a dulled and busy quietness which is never silence. Eyes open in infinite blue. A slow-winging turtle rises. I rise myself, for air, and sink again. The sea argues: back and forth, it tests me sorely – but I know these tricks and tumbles, and I have power enough in mind and body to work these waves to my delight.

Head up and out.

The shore approaches.

I am down and under, and now give way and let the water roller me in – the rocks cry out a warning – I swim sideways with all my ebbing strength – so fast so fast – and then a mighty power throws me down, hard, in whiteness. Yet I claw for life with so much longing that nothing can pull me back. Fiercely I fight – my enemy, my friend – the suck of it, guzzling and gulping at my legs. Ploughing and pushing, now in air, gasping, now under foam, I launch my body and dive for land.

My bellowing back ups and downs, unasked. My chest is first fast and roaring, then slower and slower still. Smallest of stones print my face, embed their heat in all my body. Ears whine and sing. Foam flicks and waves reach, rush, drag at my feet, trying to lure me back into water, over and again, but I resist the sea’s entreaties, crawl from its hungry reach. My head hammers and hums and stars whirl brightly in my closed eyes. I wait for all to slow, for glow to dim, for land to cease its tipping.

And then I raise my head and look up and down the beach. Nobody. Spume slides slowly on flat wet sand where sky and clouds lie spread and wrinkled. Some scattered rocks. So much sand. On and on and on all along the shore. Out of the sea’s reach, the land dries and lightens, stretches up to a wall of rock, grass at bottom and green bushes tipping from on top. Not so high you could not climb it. There will be holes for fingers and toes in the red-brown lumps and chunks. Or I will find another way to reach the houses and the children. When I can breathe. I hardly can hold my head up yet.

Thud. Thud. Thud. As this thumping lulls in head and heart, I gather strength. Here I am, Monday Island. I have come as commanded. Now it is for you to make good your promise.

Wellcome Book Prize Blog Tour: Sigrid Rausing’s Mayhem

“Now that it’s all over I find myself thinking about family history and family memories; the stories that hold a family together and the acts that can split it apart.”

Sigrid Rausing’s brother, Hans, and his wife, Eva, were wealthy philanthropists – and drug addicts who kept it together long enough to marry and have children before relapsing. Hans survived that decade-long dive back into addiction, but Eva did not: in July 2012 the 48-year-old’s decomposed body was found in a sealed-off area of the couple’s £70 million Chelsea mansion. The postmortem revealed that she had been using cocaine, which threw her already damaged heart into a chaotic rhythm. She’d been dead in their drug den for over two months.

Those are the bare facts. Scandalous enough for you? But Mayhem is no true crime tell-all. It does incorporate the straightforward information that is in the public record – headlines, statements and appearances – but blends them into a fragmentary, dreamlike family memoir that proceeds through free association and obsessively deliberates about the nature and nurture aspects of addictive personalities. “We didn’t understand that every addiction case is the same dismal story,” she writes, in a reversal of Tolstoy’s maxim about unhappy families.

Rausing’s memories of idyllic childhood summers in Sweden reminded me of Tove Jansson stories, and the incessant self-questioning of a family member wracked by remorse is similar to what I’ve encountered in memoirs and novels about suicide in the family, such as Jill Bialosky’s History of a Suicide and Miriam Toews’ All My Puny Sorrows. Despite all the pleading letters and e-mails she sent Hans and Eva, and all the interventions and rehab spells she helped arrange, Rausing has a nagging “sense that when I tried I didn’t try hard enough.”

The book moves sinuously between past and present, before and after, fact and supposition. There are a lot of peculiar details and connections in this story, starting with the family history of dementia and alcoholism. Rausing’s grandfather founded the Tetra Pak packaging company, later run by her father. Eva had a pet conspiracy theory that her father-in-law murdered Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme in 1986.

Rausing did anthropology fieldwork in Estonia and is now the publisher of Granta Books and Granta magazine. True to her career in editing, she’s treated this book project like a wild saga that had to be tamed, “all the sad and sordid details redacted,” but “I fear I have redacted too much,” she admits towards the end. She’s constantly pushing back against the more sensational aspects of this story, seeking instead to ground it in family experience. The book’s sketchy nature is in a sense necessary because information about her four nieces and nephews, of whom she took custody in 2007, cannot legally be revealed. But if she’d waited until they were all of age, might this have been a rather different memoir?

Mayhem effectively conveys the regret and guilt that plague families of addicts. It invites you to feel what it is really like to live through the “years of failed hope” that characterize this type of family tragedy. It doesn’t offer any easy lessons seen in hindsight. That makes it an uncomfortable read, but an honest one.

With thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review.

My gut feeling: This book’s style could put off more readers than it attracts. I can think of two other memoirs from the longlist that I would have preferred to see in this spot. I suppose I see why the judges rate Mayhem so highly – Edmund de Waal, the chair of this year’s judging panel, describes the Wellcome shortlist as “books that start debates or deepen them, that move us profoundly, surprise and delight and perplex us” – but it’s not in my top tier.

See what the rest of the shadow panel has to say about this book:

Annabel’s review: “Rausing is clearly a perceptive writer. She is very hard on herself; she is brutally honest, knowing that others will be hurt by the book.”

Clare’s review: “Rausing writes thoughtfully about the nature of addiction and its many contradictions.”

Laura’s review: “One of the saddest bits of Mayhem is when Rausing simply lists some of the press headlines that deal with her family story in reverse order, illustrating the seemingly inescapable spiral of addiction.”

Paul’s review: “It is not an easy read subject wise, thankfully Rausing’s sparse but beautiful writing helps makes this an essential read.”

Also, be sure to visit Laura’s blog today for an exclusive extract from Mayhem.

Shortlist strategy: Tomorrow I’ll post a quick response to Meredith Wadman’s The Vaccine Race.

If you are within striking distance of London, please consider coming to one of the shortlist events being held this Saturday and Sunday.

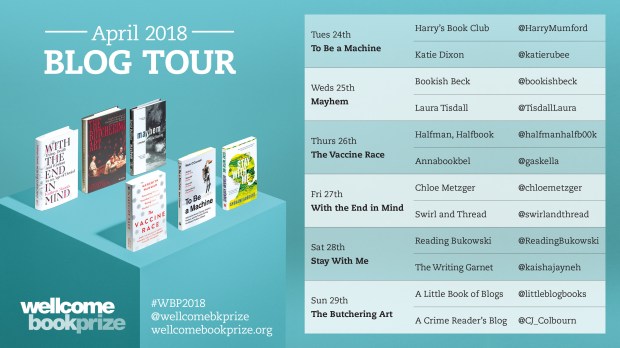

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the Wellcome Book Prize blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and extracts have appeared or will be appearing soon.

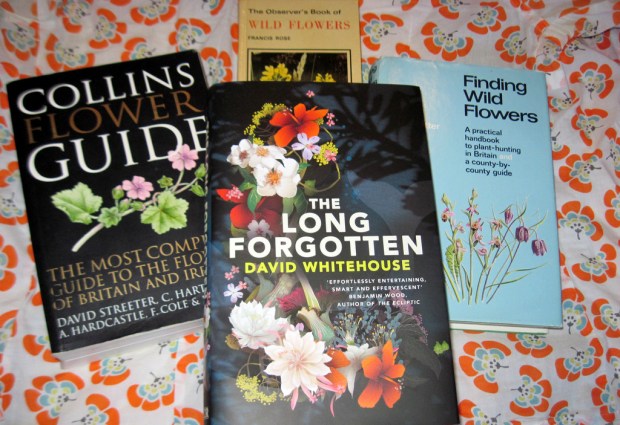

Blog Tour: The Long Forgotten by David Whitehouse

Have you noticed how many botanical titles and covers are out there this year? If you appreciate this publishing trend as much as I do, and especially if you enjoyed Susan Orlean’s The Orchid Thief, I can highly recommend The Long Forgotten. David Whitehouse’s third novel features plant hunting everywhere from Chile to Namibia, but it opens underwater: Professor Jeremiah Cole is in a submersible 200 miles west of Perth, Australia. He’s running out of oxygen down there when he collides with a goose-beaked whale that pulls his craft to the surface. The injured whale soon dies, and when the professor’s crew brings its corpse on board to perform an autopsy, they discover in its belly the black box of Flight PS570, lost on its way from Jakarta to London 30 years ago and dubbed “The Long Forgotten.”

Whitehouse’s inspiration for the novel was the Malaysian Airlines flight that went missing in 2014, along with a story he read about the Rafflesia “corpse flower” 15 years ago. After the curious incident with the whale, more gentle magic is to come as we meet Dove, a lonely young man who works as an ambulance dispatcher in present-day London and starts tuning into the memories of Peter Manyweathers. In 1980s New York City, Peter gave up cleaning the houses of the dead to chase after the exotic plants mentioned in a love letter he found in an encyclopedia. Through a local botanical etching club he met Dr. Hens Berg, a memory researcher from Denmark, who encouraged him in the quest. Soon Peter was off to China and Gibraltar to find rare plants under a washing machine or along a steep cliff face. Along the way he fell in love and had to decide whom to trust and what was of most value to him.

How Peter and Dove are connected is a mystery whose unspooling is a continual surprise. I found it quite unusual that this novel ends with the plane crash; I can think of books that start with one, like Before the Fall by Noah Hawley, but no others that end on one. This late flashback to the crash, followed by a memorial service delivered by Prof. Cole, proves that the flight’s victims are far from forgotten. The mixture of genres, including magic realism, made me think of Haruki Murakami, and Whitehouse’s style is also slightly reminiscent of Joshua Ferris and Mark Haddon. Themes of memory and family, along with vivid scenes set around the globe and bizarre plants that trap sheep or reek of death, make this book stand out. If any of these elements even vaguely appeal to you, it’s well worth taking a chance on it.

A favorite passage:

“There on a ledge no bigger than an upturned hand was the Gibraltar campion. It was about forty centimeters high, with sun-kissed green leaves, no more interesting to the casual observer than any houseplant, quite ugly even. But nestled amongst the leaves, swaying, Peter found a small and beautifully detailed bilobed flower. White from a distance, up close an ethereal explosion of colour washed across the petals, from pink to purple. Elegant and soft, but surviving here, battered like a lighthouse by the wind and waves, a candle lit inside a tempest.

Peter was overcome by the sheer unlikeliness of its existence, and felt a kinship with the flower that seemed to distort him for a second. Above them, an infinite number of galaxies, planets and possibilities. Unknowns of a number that cannot be expressed. Yet here, on a protruding ledge and at the end of a rope, endless variables had colluded to bring him and the flower together.”

My rating:

The Long Forgotten was published by Picador on March 22nd. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review, and to Anne Cater for inviting me on the blog tour.

Like so many children on both sides of the Atlantic, I grew up with Roald Dahl’s classic tales: James and the Giant Peach, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and Matilda. I was aware that he had published work for adults, too, but hadn’t experienced any of it until I was asked to join this blog tour in advance of Roald Dahl Day on September 13th.

Like so many children on both sides of the Atlantic, I grew up with Roald Dahl’s classic tales: James and the Giant Peach, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and Matilda. I was aware that he had published work for adults, too, but hadn’t experienced any of it until I was asked to join this blog tour in advance of Roald Dahl Day on September 13th.

I also dipped into Trickery: Tales of Deceit and Cunning and particularly liked “The Wish,” in which a boy imagines a carpet is a snakepit and then falls into it, and “Princess Mammalia,” a Princess Bride-style black comedy about a royal who decides to wrest power from her father but gets her mischief turned right back on her. I’ll also pick up Fear, Dahl’s curated set of ghost stories by other authors, during October for the R.I.P. challenge.

I also dipped into Trickery: Tales of Deceit and Cunning and particularly liked “The Wish,” in which a boy imagines a carpet is a snakepit and then falls into it, and “Princess Mammalia,” a Princess Bride-style black comedy about a royal who decides to wrest power from her father but gets her mischief turned right back on her. I’ll also pick up Fear, Dahl’s curated set of ghost stories by other authors, during October for the R.I.P. challenge.

Eleven-year-old Deming Guo and his mother Peilan (nicknamed “Polly”), an undocumented immigrant, live in New York City with another Fuzhounese family: Leon, Polly’s boyfriend, works in a slaughterhouse, and they share an apartment with his sister Vivian and her son Michael. Deming gets back from school one day to find that his mother never came home from her job at a nail salon. She’d been talking about moving to Florida to work in a restaurant, but how could she just leave him behind with no warning?

Eleven-year-old Deming Guo and his mother Peilan (nicknamed “Polly”), an undocumented immigrant, live in New York City with another Fuzhounese family: Leon, Polly’s boyfriend, works in a slaughterhouse, and they share an apartment with his sister Vivian and her son Michael. Deming gets back from school one day to find that his mother never came home from her job at a nail salon. She’d been talking about moving to Florida to work in a restaurant, but how could she just leave him behind with no warning?