2016 Runners-Up and Other Superlatives

Let’s hear it for the ladies! In 2016 women writers accounted for 9 out of my 15 top fiction picks, 12 out of my 15 nonfiction selections, and 8 of the 10 runners-up below. That’s 73%. The choices below are in alphabetical order by author, with any full reviews linked in. Many of these have already appeared on the blog in some form over the course of the year.

Ten Runners-Up:

FICTION

Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood: Atwood looks more like a good witch every year, and here she works her magic on The Tempest to produce the most satisfying volume of the Hogarth Shakespeare series yet. There’s a really clever play-within-the-play-within-the-play thing going on, and themes of imprisonment and performance resonate in multiple ways.

Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood: Atwood looks more like a good witch every year, and here she works her magic on The Tempest to produce the most satisfying volume of the Hogarth Shakespeare series yet. There’s a really clever play-within-the-play-within-the-play thing going on, and themes of imprisonment and performance resonate in multiple ways.

The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church: In Church’s debut, an amateur ornithologist learns about love and sacrifice through marriage to a Los Alamos physicist and a relationship with a Vietnam veteran. I instantly warmed to Meri as a narrator and loved following her unpredictable life story.

The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church: In Church’s debut, an amateur ornithologist learns about love and sacrifice through marriage to a Los Alamos physicist and a relationship with a Vietnam veteran. I instantly warmed to Meri as a narrator and loved following her unpredictable life story.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. This is a rich and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions; it’s a great first novel and I will follow Greenidge’s career with interest.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. This is a rich and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions; it’s a great first novel and I will follow Greenidge’s career with interest.

To the Bright Edge of the World by Eowyn Ivey: Ivey’s intricate second novel weaves together diaries, letters, photographs, and various other documents and artifacts to tell the gently supernatural story of an exploratory mission along Alaska’s Wolverine River in 1885 and its effects through to the present day. I can highly recommend this rollicking adventure tale to fans of historical fiction and magic realism.

by Eowyn Ivey: Ivey’s intricate second novel weaves together diaries, letters, photographs, and various other documents and artifacts to tell the gently supernatural story of an exploratory mission along Alaska’s Wolverine River in 1885 and its effects through to the present day. I can highly recommend this rollicking adventure tale to fans of historical fiction and magic realism.

This Must Be the Place by Maggie O’Farrell: Spreading outward from Ireland and reaching into every character’s past and future, this has all O’Farrell’s trademark insight into family and romantic relationships, as well as her gorgeous prose and precise imagery. I have always felt that O’Farrell expertly straddles the (perhaps imaginary) line between literary and popular fiction; her books are addictively readable but also hold up to critical scrutiny.

by Maggie O’Farrell: Spreading outward from Ireland and reaching into every character’s past and future, this has all O’Farrell’s trademark insight into family and romantic relationships, as well as her gorgeous prose and precise imagery. I have always felt that O’Farrell expertly straddles the (perhaps imaginary) line between literary and popular fiction; her books are addictively readable but also hold up to critical scrutiny.

Commonwealth by Ann Patchett: This deep study of blended family dynamics starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny; we see the aftermath of that party in the lives of six step-siblings in the decades to come. This is a sophisticated and atmospheric novel I would not hesitate to recommend to literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular.

by Ann Patchett: This deep study of blended family dynamics starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny; we see the aftermath of that party in the lives of six step-siblings in the decades to come. This is a sophisticated and atmospheric novel I would not hesitate to recommend to literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular.

The Last Painting of Sara de Vos by Dominic Smith: Jessie Burton, Tracy Chevalier and all others who try to write historical fiction about the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, eat your hearts out. Such a beautiful epoch-spanning novel about art and regret.

The Last Painting of Sara de Vos by Dominic Smith: Jessie Burton, Tracy Chevalier and all others who try to write historical fiction about the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, eat your hearts out. Such a beautiful epoch-spanning novel about art and regret.

Shelter by Jung Yun: A Korean-American family faces up to violence past and present in a strong debut that offers the hope of redemption. I would recommend this to fans of David Vann and Richard Ford.

NONFICTION

I Will Find You by Joanna Connors: By using present-tense narration, Connors makes the events of 1984 feel as if they happened yesterday: a blow-by-blow of the sex acts forced on her at knife-point over the nearly one-hour duration of her rape; the police reports and trials; and the effects it all had on her marriage and family. This is an excellent work of reconstruction and investigative reporting.

by Joanna Connors: By using present-tense narration, Connors makes the events of 1984 feel as if they happened yesterday: a blow-by-blow of the sex acts forced on her at knife-point over the nearly one-hour duration of her rape; the police reports and trials; and the effects it all had on her marriage and family. This is an excellent work of reconstruction and investigative reporting.

Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge: Younge built this book by choosing a 24-hour period (November 22 to 23, 2013) and delving into all 10 gun deaths of young Americans on record for that time: seven black, two Latino, and one white; aged nine to 18; about half at least vaguely gang-related, while in two – perhaps the most crushing cases – there was an accident while playing around with a gun. I dare anyone to read this and then try to defend gun ‘rights’ in the face of such senseless, everyday loss.

Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge: Younge built this book by choosing a 24-hour period (November 22 to 23, 2013) and delving into all 10 gun deaths of young Americans on record for that time: seven black, two Latino, and one white; aged nine to 18; about half at least vaguely gang-related, while in two – perhaps the most crushing cases – there was an accident while playing around with a gun. I dare anyone to read this and then try to defend gun ‘rights’ in the face of such senseless, everyday loss.

Various Superlatives:

Best Discoveries of the Year: Apollo Classics reprints (I reviewed three of them this year); Diana Abu-Jaber, Linda Grant and Kristopher Jansma.

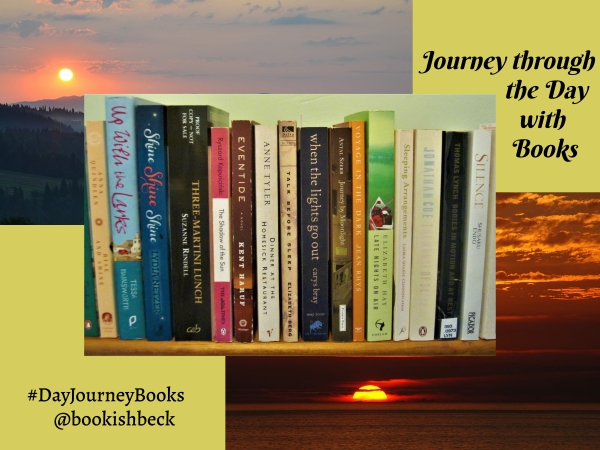

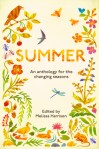

Most Pleasant Year-Long Reading Experience: The seasonal anthologies issued by the UK Wildlife Trusts and edited by Melissa Harrison (I reviewed three of them this year).

Most Improved: I heartily disliked Sarah Perry’s debut novel, After Me Comes the Flood. But her second, The Essex Serpent, is exquisite.

Debut Novelists Whose Next Work I’m Most Looking Forward to: Stephanie Danler, Kaitlyn Greenidge, Francis Spufford, Andria Williams and Sunil Yapa.

The Year’s Biggest Disappointments: Here I Am by Jonathan Safran Foer, Today Will Be Different by Maria Semple, and Swing Time by Zadie Smith. Here’s hoping 2017 doesn’t bring any letdowns from beloved authors.

The Worst Book I Read This Year: Paulina & Fran (2015) by Rachel B. Glaser. My only one-star review of the year. ’Nuff said?

The 2016 Novels I Most Wish I’d Gotten to: (At least the 10 I’m most regretful about)

- The Power by Naomi Alderman

- The Museum of You by Carys Bray

- The Course of Love by Alain de Botton

- What Belongs to You by Garth Greenwell*

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi- The Waiting Room by Leah Kaminsky

- The Inseparables by Stuart Nadler

- Harmony by Carolyn Parkhurst*

- The Nest by Cynthia D’Aprix Sweeney*

- The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead*

*Haven’t been able to find anywhere yet; the rest are on my Kindle.

Which of these should I get reading on the double?

Coming tomorrow: Some reading goals for 2017.

Review: The Girl Who Slept with God, Val Brelinski

That striking title sets the scene for an out-of-the-ordinary coming-of-age novel set in a fundamentalist Christian family in Arco, Idaho in 1970. The Quanbecks renounce dancing, movies, alcohol and everything else that represents regular teenage life for thirteen-year-old Jory. She and her sisters are sheltered from the world within their church and Christian school. That sense of being set apart only grows stronger when seventeen-year-old Grace comes back pregnant from a short mission trip to Mexico. Grace swears it was an immaculate conception and she, like Mary, has been entrusted with carrying God’s child. Is she telling the truth, is she repressing a traumatic event, or is she mentally ill? Val Brelinski keeps that question largely open throughout her strong debut novel.

That striking title sets the scene for an out-of-the-ordinary coming-of-age novel set in a fundamentalist Christian family in Arco, Idaho in 1970. The Quanbecks renounce dancing, movies, alcohol and everything else that represents regular teenage life for thirteen-year-old Jory. She and her sisters are sheltered from the world within their church and Christian school. That sense of being set apart only grows stronger when seventeen-year-old Grace comes back pregnant from a short mission trip to Mexico. Grace swears it was an immaculate conception and she, like Mary, has been entrusted with carrying God’s child. Is she telling the truth, is she repressing a traumatic event, or is she mentally ill? Val Brelinski keeps that question largely open throughout her strong debut novel.

Grace’s actions will have a lasting effect on Jory. The girls’ parents – their father a Harvard-educated astronomer and their mother a virtual shut-in who relies on prescription anxiety pills – decide that Grace will live away from them and the community, and Jory will keep her company. Dr. Quanbeck buys a small house next-door to Hilda Kleinfelter and withdraws both girls from school so word can’t get around. Jory will attend secular Schism High, where she gets an education in teenage socialization that includes the Homecoming dance, liquor and an accidental LSD trip. Hilda becomes a sort of surrogate grandmother to the girls, and Grip, a deadbeat ice cream van driver in his twenties, is their new best friend.

Brelinski is sensitive to the ways in which religion and romantic infatuation influence her characters’ choices, and even when things get a little bit uncomfortable – like when Grip and Jory steal a kiss – the plot feels true to life. The choice of close third-person narration from Jory’s perspective, rather than first-person, thankfully keeps the book from resembling a teen diary. This is the best of both worlds: we get Jory’s thoughts, but in more sophisticated literary language. The novel also blends biblical metaphors and Dr. Quanbeck’s astronomical vocabulary to good effect, as in this lovely passage near the end:

The universe had opened up and revealed its own perfectly blank face to [Jory’s] own, returning her gaze with a flattened emptiness that stretched on and on and on—a world so wide and featureless and open, so dark and formless, that light never pierced it: no sun, no moon, no stars. And it now seemed entirely possible that two girls … could stumble mutely on across the face of it forever, seeking a home, and a resting place, and finding none.

In a book full of memorable characters, I found Grace and Dr. Quanbeck to be the most compelling ones, mostly for how logic and superstition collide in their thinking. Like the father in A Song for Issy Bradley by Carys Bray, one of my favorite novels from last year, Dr. Quanbeck could almost seem like the villain here for the choices he imposes on his family, but the picture of him is nuanced so that you can see how desperately he loves his family and wants to protect them from worldly pain.

In a book full of memorable characters, I found Grace and Dr. Quanbeck to be the most compelling ones, mostly for how logic and superstition collide in their thinking. Like the father in A Song for Issy Bradley by Carys Bray, one of my favorite novels from last year, Dr. Quanbeck could almost seem like the villain here for the choices he imposes on his family, but the picture of him is nuanced so that you can see how desperately he loves his family and wants to protect them from worldly pain.

Along with Issy Bradley (set in Britain’s Mormon community), the novel reminded me most of We Sinners by Hanna Pylväinen, another picture of family life under strict religious guidelines, and How to Tell Toledo from the Night Sky by Lydia Netzer, a love story with astronomical overtones. Much as I liked it, I did think Brelinski’s novel was about a quarter too long; both the middle section – where Jory is negotiating her newfound freedom – and the dénouement felt drawn out. It would be interesting to see Brelinski’s talent for characterization and scene-setting applied to short stories or a much shorter novel. I also thought the initial decision to set the two girls up in their own home felt slightly far-fetched.

Along with Issy Bradley (set in Britain’s Mormon community), the novel reminded me most of We Sinners by Hanna Pylväinen, another picture of family life under strict religious guidelines, and How to Tell Toledo from the Night Sky by Lydia Netzer, a love story with astronomical overtones. Much as I liked it, I did think Brelinski’s novel was about a quarter too long; both the middle section – where Jory is negotiating her newfound freedom – and the dénouement felt drawn out. It would be interesting to see Brelinski’s talent for characterization and scene-setting applied to short stories or a much shorter novel. I also thought the initial decision to set the two girls up in their own home felt slightly far-fetched.

All the same, I appreciated this balanced picture of family life. The Quanbecks are never just oddities or your stereotypical dysfunctional family, but as idealistic and messed up as all the rest of us. As Mrs. Kleinfelter puts it, “Most [families] are pretty much the same, I think. Good and bad mixed together in a small bag. Or a small house.”

I received early access to this book through the Penguin First to Read program.

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

Such sentiments also reminded me of the relatable, but by no means ground-breaking, contents of

Such sentiments also reminded me of the relatable, but by no means ground-breaking, contents of  A few years ago I read Royle’s An English Guide to Birdwatching, one of the stranger novels I’ve ever come across (it brings together a young literary critic’s pet peeves, a retired couple’s seaside torture by squawking gulls, the confusion between the two real-life English novelists named Nicholas Royle, and bird-themed vignettes). It was joyfully over-the-top, full of jokes and puns as well as trenchant observations about modern life.

A few years ago I read Royle’s An English Guide to Birdwatching, one of the stranger novels I’ve ever come across (it brings together a young literary critic’s pet peeves, a retired couple’s seaside torture by squawking gulls, the confusion between the two real-life English novelists named Nicholas Royle, and bird-themed vignettes). It was joyfully over-the-top, full of jokes and puns as well as trenchant observations about modern life. Wizenberg announced her coming-out and her separation from Brandon on her blog, so I was aware of all this for the last few years and via

Wizenberg announced her coming-out and her separation from Brandon on her blog, so I was aware of all this for the last few years and via  It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?!

It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?! My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.

My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.

This collects 45 super-short stories that stand out for their structure, voice, and character development—all in spite of often extreme brevity. Humor and pathos provide sharp pivot points. It helps to have an unusual perspective, like that of a Venus flytrap observing a household’s upheavals (Janey Skinner’s “Carnivores”), or of potential names gathering around a baptismal font (Alberto Chimal’s “The Waterfall”). Hard as it is to choose from such a diverse bunch, I do have three favorites: Elizabeth Morton’s “Parting,” in which a divorce causes things to be literally divided; Mary-Jane Holmes’s “Trifle,” where alliteration and culinary vocabulary contrast an English summer with Middle Eastern traces; and Amir Adam’s “The Physics of Satellites,” which uses images from astronomy and a recent suicide to contrast falling, flying, and barely holding on. There are fewer highlights than in

This collects 45 super-short stories that stand out for their structure, voice, and character development—all in spite of often extreme brevity. Humor and pathos provide sharp pivot points. It helps to have an unusual perspective, like that of a Venus flytrap observing a household’s upheavals (Janey Skinner’s “Carnivores”), or of potential names gathering around a baptismal font (Alberto Chimal’s “The Waterfall”). Hard as it is to choose from such a diverse bunch, I do have three favorites: Elizabeth Morton’s “Parting,” in which a divorce causes things to be literally divided; Mary-Jane Holmes’s “Trifle,” where alliteration and culinary vocabulary contrast an English summer with Middle Eastern traces; and Amir Adam’s “The Physics of Satellites,” which uses images from astronomy and a recent suicide to contrast falling, flying, and barely holding on. There are fewer highlights than in

These nine stories examine what characters do in extreme, often violent situations. My three favorites were “Bunny,” reminiscent of The Fattest Man in Britain with its picture of a friendship between an obese man and a young woman who sees more in him than his size; “The Woodpecker and the Wolf,” a brilliantly suspenseful tale set in space – it reminded me of the Sandra Bullock movie Gravity; and “The Weir,” which imagines the unexpectedly lasting relationship between a lonely middle-aged man and the young woman he rescues from a near-suicide by drowning. “Wodwo” starts off as a terrific Christmas horror story but goes on far too long and loses power. I would say that about several of these stories, actually: they’re that bit too long, so that you start waiting for them to be over. I prefer sudden endings that give a bit of a kick. All in all, though, two-thirds of the stories are fairly memorable, and I’d say I liked this better than any of Haddon’s three novels.

These nine stories examine what characters do in extreme, often violent situations. My three favorites were “Bunny,” reminiscent of The Fattest Man in Britain with its picture of a friendship between an obese man and a young woman who sees more in him than his size; “The Woodpecker and the Wolf,” a brilliantly suspenseful tale set in space – it reminded me of the Sandra Bullock movie Gravity; and “The Weir,” which imagines the unexpectedly lasting relationship between a lonely middle-aged man and the young woman he rescues from a near-suicide by drowning. “Wodwo” starts off as a terrific Christmas horror story but goes on far too long and loses power. I would say that about several of these stories, actually: they’re that bit too long, so that you start waiting for them to be over. I prefer sudden endings that give a bit of a kick. All in all, though, two-thirds of the stories are fairly memorable, and I’d say I liked this better than any of Haddon’s three novels.  Kleeman’s debut novel,

Kleeman’s debut novel,

On Tuesday I finished All That Man Is by David Szalay, from the Booker Prize shortlist. Whether it’s a novel or actually short stories is certainly a matter for debate! After I read Madeleine Thien’s shortlisted novel (I’ll be picking it up from the library on Friday) I’ll report back on both in advance of the prize announcement at the end of October.

On Tuesday I finished All That Man Is by David Szalay, from the Booker Prize shortlist. Whether it’s a novel or actually short stories is certainly a matter for debate! After I read Madeleine Thien’s shortlisted novel (I’ll be picking it up from the library on Friday) I’ll report back on both in advance of the prize announcement at the end of October. I’m also currently making my way through How Much the Heart Can Hold, a set of seven stories from the likes of Carys Bray and Donal Ryan on the theme of different types of love, and Petina Gappah’s forthcoming collection, Rotten Row. (Both are out in early November.)

I’m also currently making my way through How Much the Heart Can Hold, a set of seven stories from the likes of Carys Bray and Donal Ryan on the theme of different types of love, and Petina Gappah’s forthcoming collection, Rotten Row. (Both are out in early November.) You Are Having a Good Time: Stories by Amie Barrodale

You Are Having a Good Time: Stories by Amie Barrodale

Sweet Home by Carys Bray

Sweet Home by Carys Bray

Parfums: A Catalogue of Remembered Smells by Philippe Claudel

Parfums: A Catalogue of Remembered Smells by Philippe Claudel  Absalom’s Daughters by Suzanne Feldman

Absalom’s Daughters by Suzanne Feldman

The Hemingway Thief by Shaun Harris

The Hemingway Thief by Shaun Harris Setting Free the Bears by John Irving

Setting Free the Bears by John Irving