#1952Club: Patricia Highsmith, Paul Tillich & E.B. White

Simon and Karen’s classics reading weeks are always a great excuse to pick up some older books. I assembled an unlikely trio of lesbian romance, niche theology, and an animal-lover’s children’s classic.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith

Originally published as The Price of Salt under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, this is widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending (it’s more open-ended, really, but certainly not tragic; suicide was a common consequence in earlier fiction). Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer in New York City, takes a job selling dolls in a department store one Christmas season. Her boyfriend, Richard, is a painter and has promised to take her to Europe, but she’s lukewarm about him and the physical side of their relationship has never interested her. One day, a beautiful blonde woman in a fur coat – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – comes to her counter to order a doll and have it sent to her out in New Jersey. Therese sends a Christmas card to the same address, and the women start meeting up for drinks and meals.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

The second half of the book has Carol and Therese setting out on a road trip out West. It should be an idyllic consummation, but they realize they’re being trailed by a private detective collecting evidence for Carol’s husband Harge to use against her in a custody battle. I was reminded of the hunt for Humbert Humbert and his charge in Lolita; “the whole world was ready to be their enemy,” Therese realizes, and to consider their relationship “sordid and pathological,” as Richard describes it in a letter.

The novel is a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds against it. I’d read five of Highsmith’s mysteries and thought them serviceable but nothing special (I don’t read crime in general). This does, however, share their psychological intensity and the suspense about how things will play out. Highsmith gives details about Therese’s early life and Carol’s previous intimate friendship that help to explain some things but never reduce either character to a diagnosis or a tendency. Neither of them wanted just anyone, some woman; it was this specific combination of souls that sparked at first sight. (Secondhand from a charity shop that closed long ago, so I know I’d had it on my shelf unread since 2016!) ![]()

The Courage to Be by Paul Tillich

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

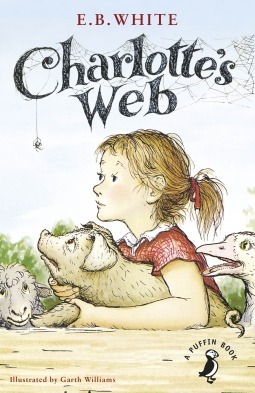

Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

Charlotte is a fine specimen of a barn spider, well spoken and witty. She puts her mind to saving Wilbur’s bacon by weaving messages into her web, starting with “Some Pig.” He’s soon a county-wide spectacle, certain to survive the chop. But a farm is always, inevitably, a place of death. White fashions such memorable characters, including Templeton the gluttonous rat, and captures the hope of new life returning as the seasons turn over. Talking animals aren’t difficult to believe in when Fern can hear every word they say. The black-and-white line drawings are adorable. And making readers care about invertebrates? That’s a lasting achievement. I’m sure I read this several times as a child, but I appreciated it all the more as an adult. (Little Free Library) ![]()

I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, 1940 Club, 1937 Club, and 1970 Club.

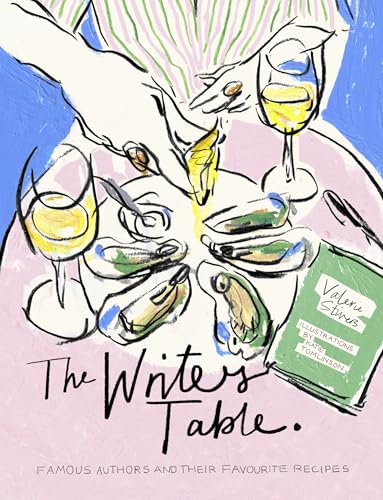

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”