Reviewing Two Books by Cancelled Authors

I don’t have anything especially insightful to say about these authors’ reasons for being cancelled, although in my review of the Clanchy I’ve noted the textual examples that have been cited as problematic. Alexie is among the legion of male public figures to have been accused of sexual misconduct in recent years. I’m not saying those aren’t serious allegations, but as Claire Dederer wrestled with in Monsters, our judgement of a person can be separate from our response to their work. So that’s the good news: I thought these were both fantastic books. They share a theme of education.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (illus. Ellen Forney) (2007)

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

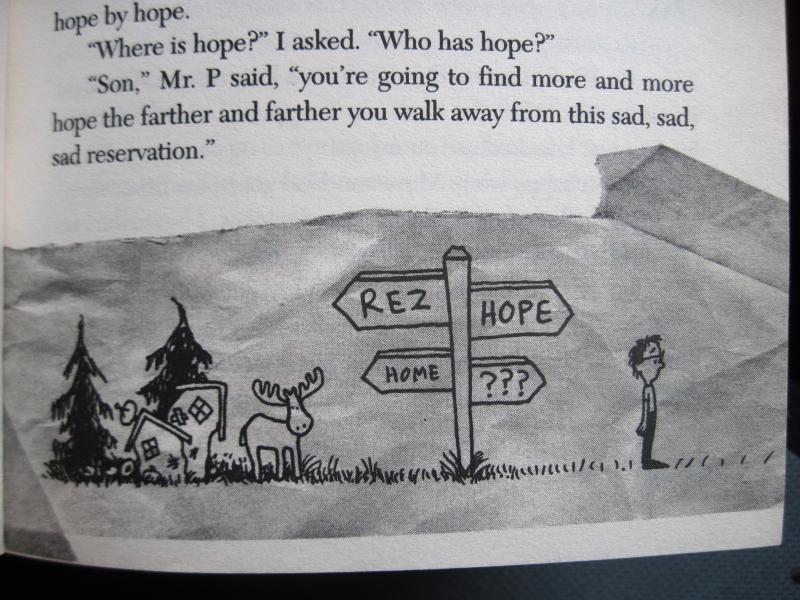

It reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable; Alexie’s tone is spot on. Junior has had a tough life on a Spokane reservation in Washington, being bullied for his poor eyesight and speech impediments that resulted from brain damage at birth and ongoing seizures. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations here because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior’s parents never got to pursue their dreams and his sister has run away to Montana, but he has a chance to change the trajectory. A rez teacher says his only hope for a bright future is to transfer to the elite high school in Reardan. So he does, even though it often requires hitch-hiking or walking miles.

Junior soon becomes adept at code-switching: “Traveling between Reardan and Wellpinit, between the little white town and the reservation, I always felt like a stranger. I was half Indian in one place and half white in the other.” He gets a white girlfriend, Penelope, but has to work hard to conceal how impoverished he is. His best friend, Rowdy, is furious with him for abandoning his people. That resentment builds all the way to a climactic basketball match between Reardan and Wellpinit that also functions as a symbolic battle between the parts of Junior’s identity. Along the way, there are multiple tragic deaths in which alcohol, inevitably, plays a role. “I’m fourteen years old and I’ve been to forty-two funerals,” he confides. “Jeez, what a sucky life. … I kept trying to find the little pieces of joy in my life. That’s the only way I managed to make it through all of that death and change.”

One of those joys, for him, is cartooning. Describing his cartoons to his new white friend, Gordy, he says, “I use them to understand the world.”

Forney’s black-and-white illustrations make the cartoons look like found objects – creased scraps of notebook paper sellotaped into a diary. This isn’t a graphic novel, but most of the short chapters include several illustrations. There’s a casual intimacy to the whole book that feels absolutely authentic. Bridging the particular and universal, it’s a heartfelt gem, and not just for teens. (University library) ![]()

Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy (2019)

If your Twitter sphere and mine overlap, you may remember the controversy over the racialized descriptions in this Orwell Prize-winning memoir of 30 years of teaching – and the fact that, rather than issuing a humbled apology, Clanchy, at least initially, doubled down and refuted all objections, even when they came from BIPOC. It wasn’t a good look. Nor was it the first time I’ve found Clanchy to be prickly. (She is what, in another time, might have been called a formidable woman.) Anyway, I waited a few years for the furore to die down before trying this for myself.

I know vanishingly little about the British education system because I don’t have children and only experienced uni here at a distance, through my junior year abroad. So there may be class-based nuances I missed – for instance, in the chapter about selecting a school for her oldest son and comparing it with the underprivileged Essex school where she taught. But it’s clear that a lot of her students posed serious challenges. Many were refugees or immigrants, and she worked for a time on an “Inclusion Unit,” which seems to be more in the business of exclusion in that it’s for students who have been removed from regular classrooms. They came from bad family situations and were more likely to end up in prison or pregnant. To get any of them to connect with Shakespeare, or write their own poetry, was a minor miracle.

Clanchy is also a poet and novelist – I’ve read one of her novels, and her Selected Poems – and did much to encourage her students to develop a voice and the confidence to have their work published (she’s produced anthologies of student work). In many cases, she gave them strategies for giving literary shape to traumatic memories. The book’s engaging vignettes have all had the identifying details removed, and are collected under thematic headings that address the second part of the title: “About Love, Sex, and the Limits of Embarrassment” and “About Nations, Papers, and Where We Belong” are two example chapters. She doesn’t avoid contentious topics, either: the hijab, religion, mental illness and so on.

You get the feeling that she was a friend and mentor to her students, not just their teacher, and that they could talk to her about anything and rely on her support. Watching them grow in self-expression is heart-warming; we come to care for these young people, too, because of how sincerely they have been created from amalgams. Indeed, Clanchy writes in the introduction that “I have included nobody, teacher or pupil, about whom I could not write with love.”

And that is, I think, why she was so hurt and disbelieving when people pointed out racism in her characterization:

I was baffled when a boy with jet-black hair and eyes and a fine Ashkenazi nose named David Marks refused any Jewish heritage

her furry eyebrows, her slanting, sparking black eyes, her general, Mongolian ferocity. [but she’s Afghan??]

(of girls in hijabs) I never saw their (Asian/silky/curly?) hair in eight years.

They’re a funny pair: Izzat so small and square and Afghan with his big nose and premature moustache; Mo so rounded and mellow and Pakistani with his long-lashed eyes and soft glossy hair.

There are a few other ill-advised passages. She admits she can’t tell the difference between Kenyan and Somali faces; she ponders whether being a Scot in England gave her some taste of the prejudice refugees experience. And there’s this passage about sexuality:

Are we all ‘fluid’ now? Perhaps. It is commonplace to proclaim oneself transsexual. And to actually be gay, especially if you are as pretty as Kristen Stewart, is positively fashionable. A couple of kids have even changed gender, a decision … deliciously of the moment

My take: Clanchy wanted to craft affectionate pen portraits that celebrated children’s uniqueness, but had to make them anonymous, so resorted to generalizations. Doing this on a country or ethnicity basis was the mistake. Journalistic realism doesn’t require a focus on appearances (I would hope that, if I were ever profiled, someone could find more interesting things to say about me than that I am short and have a large nose). She could have just introduced the students with ‘facts,’ e.g., “Shakila, from Afghanistan, wore a hijab and was feisty and outspoken.” Note to self: white people can be clueless, and we need to listen and learn. The book was reissued in 2022 by independent publisher Swift Press, with offending passages removed (see here for more info). I’d be keen to see the result and hope that the book will find more readers because, truly, it is lovely. (Little Free Library) ![]()

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (#NovNov Nonfiction Buddy Read)

For nonfiction week of Novellas in November, our buddy read is The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (1903). You can download the book for free from Project Gutenberg here if you’d still like to join in.

Keller’s story is culturally familiar to us, perhaps from the William Gibson play The Miracle Worker, but I’d never read her own words. She was born in Alabama in 1880; her father had been a captain in the Confederate Army. An illness (presumed to be scarlet fever) left her blind and deaf at the age of 19 months, and she describes herself in those early years as mischievous and hot-tempered, always frustrated at her inability to express herself. The arrival of her teacher, Anne Sullivan, when Helen was six years old transformed her “silent, aimless, dayless life.”

I was fascinated by the glimpses into child development and education. Especially after she learned Braille, Keller loved books, but she believed she learned just as much from nature: “everything that could hum or buzz, or sing, or bloom, had a part in my education.” She loved to sit in the family orchard and would hold insects or fossils and track plant and tadpole growth. Her first trip to the ocean (Chapter 10) was a revelation, and rowing and sailing became two of her chief hobbies, along with cycling and going to the theatre and museums.

At age 10 Keller relearned to speak – a more efficient way to communicate than her usual finger-spelling. She spent winters in Boston and eventually attended the Cambridge School for Young Ladies in preparation for starting college at Radcliffe. Her achievements are all the more remarkable when you consider that smell and touch – senses we tend to overlook – were her primary ones. While she used a typewriter to produce schoolwork, a teacher spelling into her hand was still her main way to intake knowledge. Specialist textbooks for mathematics and multiple languages were generally not available in Braille. Digesting a lesson and completing homework thus took her much longer than it did her classmates, but still she felt “impelled … to try my strength by the standards of those who see and hear.”

It was surprising to find, at the center of the book, a detailed account of a case of unwitting plagiarism (Chapter 14). Eleven-year-old Keller wrote a story called “The Frost King” for a beloved teacher at the Perkins Institution for the Blind. He was so pleased that he printed it in one of their publications, but it soon came to his attention that the plot was very similar to “The Frost Fairies” in Birdie and His Friends by Margaret T. Canby. The tale must have been read to Keller long ago but become so deeply buried in the compost of a mind’s memories that she couldn’t recall its source. Some accused Keller and Sullivan of conspiring, and this mistrust more than the incident itself cast a shadow over her life for years to come. I was impressed by Keller discussing in depth something that it would surely have been more comfortable to bury. (I’ve sometimes had the passing thought that if I wrote a memoir I would structure it around my regrets or most embarrassing moments. Would that be penance or masochism?)

This short memoir was first serialized in the Ladies’ Home Journal. Keller was only 23 and partway through her college degree at the time of publication. An initial chronological structure later turns more thematic and the topics are perhaps a little scattershot. I would attribute this, at least in part, to the method of composition: it would be difficult to make large-scale edits on a manuscript because everything she typed had to be spelled back to her for approval. Minor line edits would be easy enough, but not big structural changes. (I wonder if it’s similar with work that’s been dictated, like May Sarton’s later journals.)

Helen Keller in graduation cap and gown. (PPOC, Library of Congress. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Keller went on to write 12 more books. It would be interesting to follow up with another one to learn about her travels and philanthropic work. For insight into a different aspect of her life – bearing in mind that it’s fiction – I recommend Helen Keller in Love by Rosie Sultan. In a couple of places Keller mentions Laura Bridgman, her less famous predecessor in the deaf–blind community; Kimberly Elkins’ 2014 What Is Visible is a stunning novel about Bridgman.

For such a concise book – running to just 75 pages in my Dover Thrift Editions paperback – this packs in so much. Indeed, I’ve found more to talk about in this review than I might have expected. The elements that most intrigued me were her early learning about abstractions like love and thought, and her enthusiastic rundown of her favorite books: “In a word, literature is my Utopia. Here I am not disenfranchised. No barrier of the senses shuts me out from the sweet, gracious discourse of my book-friends.”

It’s possible some readers will find her writing style old-fashioned. It would be hard to forget you’re reading a work from nearly 120 years ago, given the sentimentality and religious metaphors. But the book moves briskly between anecdotes, with no filler. I remained absorbed in Keller’s story throughout, and so admired her determination to obtain a quality education. I know we’re not supposed to refer to disabled authors’ work as “inspirational,” so instead I’ll call it both humbling and invigorating – a reminder of my privilege and of the force of the human will. (Secondhand purchase, Barter Books)

Also reviewed by:

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

This is not about

This is not about

The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes was the other book I popped in the back of my purse for yesterday’s London outing. Barnes is one of my favourite authors – I’ve read 21 books by him now! – but I remember not being very taken with this Booker winner when I read it just over 10 years ago. (I prefer to think of his win as being for his whole body of work as he’s written vastly more original and interesting books, like

The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes was the other book I popped in the back of my purse for yesterday’s London outing. Barnes is one of my favourite authors – I’ve read 21 books by him now! – but I remember not being very taken with this Booker winner when I read it just over 10 years ago. (I prefer to think of his win as being for his whole body of work as he’s written vastly more original and interesting books, like  The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark was January’s book club selection. I had remembered no details apart from the title character being a teacher. It’s a between-the-wars story set in Edinburgh. Miss Brodie’s pet students are girls with attributes that remind her of aspects of herself. Our group was appalled at what we today would consider inappropriate grooming, and at Miss Brodie’s admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. Educational theory was interesting to think about, however. Spark’s work is a little astringent for me, and I also found this one annoyingly repetitive on the sentence level. (Public library)

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark was January’s book club selection. I had remembered no details apart from the title character being a teacher. It’s a between-the-wars story set in Edinburgh. Miss Brodie’s pet students are girls with attributes that remind her of aspects of herself. Our group was appalled at what we today would consider inappropriate grooming, and at Miss Brodie’s admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. Educational theory was interesting to think about, however. Spark’s work is a little astringent for me, and I also found this one annoyingly repetitive on the sentence level. (Public library)

Brit-Think, Ameri-Think: A Transatlantic Survival Guide by Jane Walmsley: This is the revised edition from 2003, so I must have bought it as preparatory reading for my study abroad year in England. This may even be the third time I’ve read it. Walmsley, an American in the UK, compares Yanks and Brits on topics like business, love and sex, parenting, food, television, etc. I found my favourite lines again (in a panel entitled “Eating in Britain: Things that Confuse American Tourists”): “Why do Brits like snacks that combine two starches? (a) If you’ve got spaghetti, do you really need the toast? (b) What’s a ‘chip-butty’? Is it fatal?” The explanation of the divergent sense of humour is still spot on, and I like the Gray Jolliffe cartoons. Unfortunately, a lot of the rest feels dated – she’d updated it to 2003’s pop culture references, but these haven’t aged well. (New purchase?)

Brit-Think, Ameri-Think: A Transatlantic Survival Guide by Jane Walmsley: This is the revised edition from 2003, so I must have bought it as preparatory reading for my study abroad year in England. This may even be the third time I’ve read it. Walmsley, an American in the UK, compares Yanks and Brits on topics like business, love and sex, parenting, food, television, etc. I found my favourite lines again (in a panel entitled “Eating in Britain: Things that Confuse American Tourists”): “Why do Brits like snacks that combine two starches? (a) If you’ve got spaghetti, do you really need the toast? (b) What’s a ‘chip-butty’? Is it fatal?” The explanation of the divergent sense of humour is still spot on, and I like the Gray Jolliffe cartoons. Unfortunately, a lot of the rest feels dated – she’d updated it to 2003’s pop culture references, but these haven’t aged well. (New purchase?)