Two Mother–Daughter Author Pairs for Mother’s Day

This coming Sunday is Mother’s Day in the USA. (Mothering Sunday generally falls in March here in the UK, so every year I have to buy a card early to send to my mother back in the States, but I still associate Mother’s Day with May.) Earlier in the year I got over halfway through a Goodreads giveaway book, Beyond the Pale by Emily Urquhart, before I realized its author was the daughter of a Canadian novelist I’d read before, Jane Urquhart. That got me thinking about other mother–daughter pairs that might be on my shelves. I found one in the form of Sue Monk Kidd’s The Secret Life of Bees plus an advance e-copy of her daughter Ann Kidd Taylor’s upcoming debut novel, The Shark Club. (I’ve previously reviewed their joint memoir, Traveling with Pomegranates.) And, as a bonus, I have a mini-review of Graham Swift’s novella Mothering Sunday: A Romance.

The Whirlpool, Jane Urquhart

From 1986, this was Urquhart’s first novel. Overall it reminded me of A. S. Byatt (especially The Virgin in the Garden) and John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Set in 1889 on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, it features characters who, each in their separate ways, are stuck in the past and obsessed with death and its symbolic stand-in, the whirlpool. Maud Grady, the local undertaker’s widow, takes possession of the corpses of those who’ve tried to swim the Falls. Her creepy young son starts off mute and becomes an expert mimic. Major David McDougal is fixated on the War of 1812, while his wife Fleda camps out in a tent reading Victorian poetry, especially Robert Browning, and awaiting a house that may never be built. Local poet Patrick sees Fleda from afar and develops romanticized ideas about her.

From 1986, this was Urquhart’s first novel. Overall it reminded me of A. S. Byatt (especially The Virgin in the Garden) and John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Set in 1889 on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, it features characters who, each in their separate ways, are stuck in the past and obsessed with death and its symbolic stand-in, the whirlpool. Maud Grady, the local undertaker’s widow, takes possession of the corpses of those who’ve tried to swim the Falls. Her creepy young son starts off mute and becomes an expert mimic. Major David McDougal is fixated on the War of 1812, while his wife Fleda camps out in a tent reading Victorian poetry, especially Robert Browning, and awaiting a house that may never be built. Local poet Patrick sees Fleda from afar and develops romanticized ideas about her.

Each of these narratives is entertaining, but I was less convinced by their intersections – except for the brilliant scenes when Patrick and Maud’s son engage in wordplay. In particular, I was unsure what the prologue and epilogue (in which Robert Browning, dying in Venice, is visited by images of Shelley’s death by drowning) were meant to add. This is the second Urquhart novel I’ve read, after Sanctuary Line. I admire her writing but her plots don’t always come together. However, I’m sure to try more of her work: I have a copy of Away on the shelf, and Changing Heaven (1990) sounds unmissable – it features the ghost of Emily Brontë! [Bought from a Lambeth charity shop for 20p.]

My rating:

Beyond the Pale: Folklore, Family and the Mystery of Our Hidden Genes, Emily Urquhart

In December 2010, the author’s first child, Sadie, was born with white hair. It took weeks to confirm that Sadie had albinism, a genetic condition associated with extreme light sensitivity and poor eyesight. A Canadian folklorist, Urquhart is well placed to trace the legends that have arisen about albinos through time and across the world, ranging from the Dead Sea Scroll story of Noah being born with blinding white skin and hair to the enduring superstition that accounts for African albinos being maimed or killed to use their body parts in folk medicine.

In December 2010, the author’s first child, Sadie, was born with white hair. It took weeks to confirm that Sadie had albinism, a genetic condition associated with extreme light sensitivity and poor eyesight. A Canadian folklorist, Urquhart is well placed to trace the legends that have arisen about albinos through time and across the world, ranging from the Dead Sea Scroll story of Noah being born with blinding white skin and hair to the enduring superstition that accounts for African albinos being maimed or killed to use their body parts in folk medicine.

She attends a NOAH (America’s National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation) conference, discovers potential evidence of a family history of albinism, and even makes a pilgrimage to Tanzania to meet some victims. It’s all written up in as engaging present-tense narrative of coming to terms with disability: to start with Urquhart is annoyed at people reassuring her “it could be worse,” but by the end she’s ever so slightly disappointed to learn that her second child, a boy, will not be an albino like his sister. [Goodreads giveaway copy]

My rating:

The Secret Life of Bees, Sue Monk Kidd

It’s hard to believe it was 15 years ago that this debut novel was an It book, and harder to believe that I’d never managed to get around to it until now. However, in some ways it felt familiar because I’d read a fair bit of background via Kidd’s chapter in Why We Write about Ourselves and Traveling with Pomegranates, in which she and her daughter explored the Black Madonna tradition in Europe.

It’s hard to believe it was 15 years ago that this debut novel was an It book, and harder to believe that I’d never managed to get around to it until now. However, in some ways it felt familiar because I’d read a fair bit of background via Kidd’s chapter in Why We Write about Ourselves and Traveling with Pomegranates, in which she and her daughter explored the Black Madonna tradition in Europe.

It joins unusual elements you wouldn’t expect to find in fiction – beekeeping and the divine feminine – with more well-trodden territory: the Civil Rights movement in the South in the 1960s, unhappy family relationships, secrets, and a teenage girl’s coming of age. Fourteen-year-old Lily is an appealing narrator who runs away from her memories of her mother’s death and her angry father, peach farmer T. Ray. You can’t help but fall in love with the rest of her new African-American, matriarchal clan, including their housekeeper, Rosaleen, who scandalizes the town by registering to vote, and the bee-keeping Boatwright sisters, August, June, and May, who give Lily and Rosaleen refuge when they skip town.

Although this crams in a lot of happenings and emotional ups and downs, it’s a charming story that draws you into the brutal heat of a South Carolina summer and keeps you hoping Lily will forgive herself and slip into the rhythms of a purposeful life of sisterhood. [Secondhand purchase in America]

A favorite line: “The way people lived their lives, settling for grits and cow shit, made me sick.”

My rating:

The Shark Club, Ann Kidd Taylor

Dr. Maeve Donnelly loves sharks even though she was bitten by one as a child. She’s now a leading researcher with a Florida conservancy and travels around the world to gather data. Her professional life goes from strength to strength, but her personal life is another matter. Aged 30, she’s smarting from a broken engagement to her childhood sweetheart, Daniel, and isn’t ready to open her heart to Nicholas, a British colleague going through a divorce.

Dr. Maeve Donnelly loves sharks even though she was bitten by one as a child. She’s now a leading researcher with a Florida conservancy and travels around the world to gather data. Her professional life goes from strength to strength, but her personal life is another matter. Aged 30, she’s smarting from a broken engagement to her childhood sweetheart, Daniel, and isn’t ready to open her heart to Nicholas, a British colleague going through a divorce.

Things get complicated when Daniel returns to their southwest Florida island to work as the chef at her grandmother’s hotel – with his six-year-old daughter in tow. Maeve is soon taken with precocious Hazel, who founds the title club (pledge: “With this fin, I do swear. To love sharks even when they bite. When they lose their teeth, I will find them. When I catch one, I will let it go”), but isn’t sure she can pick up where she left off with Daniel. Meanwhile, evidence has surfaced of a local shark finning operation, and she’s determined to get to the bottom of it.

This is a little bit romance and a little bit mystery, and Taylor brings the Florida Keys setting to vibrant life. It took a while to suspend disbelief about Maeve’s background – an orphan and a twin and a shark bite survivor and a kid brought up in a hotel? – but I enjoyed the sweet yet unpredictable story line. Nothing earth-shattering, but great light reading for a summer day at the beach. Releases June 6th from Viking. [Edelweiss download]

My rating:

Mothering Sunday: A Romance, Graham Swift

If you’re expecting a cozy tale of maternal love, let the Modigliani nude on the U.K. cover wipe that notion out of your mind. Part of me was impressed by Swift’s compact picture of one sexy, fateful day in 1924 and the reverberations it had for a budding writer even decades later. Interesting class connotations, too. But another part of me thought, isn’t this what you would get if Ian McEwan directed a middling episode of Downton Abbey? It has undeniable similarities to Atonement and On Chesil Beach, after all, and unlike those novels it’s repetitive; it keeps cycling round to restate its main events and points. There’s some good lines, but overall this felt like a strong short story stretched out to try to achieve book length. [Library read]

If you’re expecting a cozy tale of maternal love, let the Modigliani nude on the U.K. cover wipe that notion out of your mind. Part of me was impressed by Swift’s compact picture of one sexy, fateful day in 1924 and the reverberations it had for a budding writer even decades later. Interesting class connotations, too. But another part of me thought, isn’t this what you would get if Ian McEwan directed a middling episode of Downton Abbey? It has undeniable similarities to Atonement and On Chesil Beach, after all, and unlike those novels it’s repetitive; it keeps cycling round to restate its main events and points. There’s some good lines, but overall this felt like a strong short story stretched out to try to achieve book length. [Library read]

My rating:

Now in November by Josephine Johnson

I’d never heard of this 1935 Pulitzer Prize winner before I saw a large display of titles from publisher Head of Zeus’s new imprint, Apollo, at Foyles bookshop in London the night of the Diana Athill event. Apollo, which launched with eight titles in April, aims to bring lesser-known classics out of obscurity: by making “great forgotten works of fiction available to a new generation of readers,” it intends to “challenge the established canon and surprise readers.” I’ll be reviewing Howard Spring’s My Son, My Son for Shiny New Books soon, and I’m tempted by the Eudora Welty and Christina Stead titles. Rounding out the list are two novels set in Eastern Europe, a Sardinian novel in translation, and an underrated Western.

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. She recognizes how unsuited her father, Arnold, was to farming: “He hadn’t the resignation that a farmer has to have – that resignation which knows how little use to hope or hate.” The remaining members of this female-dominated household are mother Willa, older sister Kerrin and younger sister Merle. Half-feral Kerrin is a creature apart. She’s always doing something unpredictable, like demonstrating knife-throwing to disastrous effect or taking over as the local schoolteacher, a job she’s not at all right for.

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. She recognizes how unsuited her father, Arnold, was to farming: “He hadn’t the resignation that a farmer has to have – that resignation which knows how little use to hope or hate.” The remaining members of this female-dominated household are mother Willa, older sister Kerrin and younger sister Merle. Half-feral Kerrin is a creature apart. She’s always doing something unpredictable, like demonstrating knife-throwing to disastrous effect or taking over as the local schoolteacher, a job she’s not at all right for.

The arrival of Grant Koven, a neighbor in his thirties hired to help Arnold with hard labor, seems like the only thing that might break the agricultural cycle of futile hope and disappointment. Marget quickly falls in love with him, but it takes her a while to realize that her sisters are smitten too. They all keep hoping their fortunes will change:

‘This year will have to be different,’ I thought. ‘We’ve scrabbled and prayed too long for it to end as the others have.’ The debt was still like a bottomless swamp unfilled, where we had gone year after year, throwing in hours of heat and the wrenching on stony land, only to see them swallowed up and then to creep back and begin again.

Yet as drought settles in, things only get worse. The fear of losing everything becomes a collective obsession; a sense of insecurity pervades the community. The Ramseys, black tenant farmers with nine children, are evicted. Milk producers go on strike and have to give the stuff away before it sours. Nature is indifferent and neither is there a benevolent God at work: when the Haldmarnes go to church, they are refused communion as non-members.

Marget skips around in time to pinpoint the central moments of their struggle, her often fragmentary thoughts joined by ellipses – a style that seemed to me ahead of its time:

if anything could fortify me against whatever was to come […] it would have to be the small and eternal things – the whip-poor-wills’ long liquid howling near the cave… the shape of young mules against the ridge, moving lighter than bucks across the pasture… things like the chorus of cicadas, and the ponds stained red in evenings.

Michael Schmidt, the critic who selected the first eight Apollo books, likens Now in November to the work of two very different female writers: Marilynne Robinson and Emily Brontë. What I think he is emphasizing with those comparisons is the sense of isolation and the feeling that struggle is writ large on the landscape. The Haldmarne sisters certainly wander the nearby hills like the Brontë sisters did the Yorkshire moors.

The cover image, reproduced in full on the endpapers, is Jackson Pollock’s “Man with Hand Plow,” c. 1933.

As points of reference I would also add Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres and Joan Chase’s During the Reign of the Queen of Persia (resurrected by NYRB Classics in 2014), which also give timeless weight to the female experience of Midwest farming. Like the Smiley, Now in November stars a trio of sisters and makes conscious allusions to King Lear. Kerrin reads the play and thinks of their father as Lear, while Marget quotes it as a prophecy that the worst is yet to come: “I remembered the awful words in Lear: ‘The worst is not so long as we can say “This is the worst.”’ Already this year, I’d cried, This is enough! uncounted times, and the end had never come.”

Johnson lived to age 80 and published another 11 books, but nothing ever lived up to the success of her first. This is an atmospheric and strangely haunting novel. The plot is simple enough, but the writing elevates it into something special. The plaintive tone, the folksy metaphors, and the philosophical earnestness all kept me eagerly traveling along with Marget to see where this tragic story might lead. Apollo has done the literary world a great favor in bringing this lost classic to light.

With thanks to Blake Brooks at Head of Zeus for the free copy.

My rating:

Happy 200th Birthday, Charlotte Brontë!

Today marks a big anniversary: the bicentennial of Charlotte Brontë’s birth. I’ve noticed a whole cluster of books being published or reissued in time for her 200th birthday, many of which I’ve reviewed with enjoyment; some of which I’ve sampled and left unfinished. I hope you’ll find at least one book on this list that will take your fancy. There could be no better time for going back to Charlotte Brontë’s timeless stories and her quiet but full life story.

Short Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre

MINOR SPOILERS AHEAD.

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre, edited by Tracy Chevalier

Reader, I Married Him: Stories Inspired by Jane Eyre, edited by Tracy Chevalier

A mixed bag. Although there are some very good stand-alone stories (from Tessa Hadley, Sarah Hall, Emma Donoghue and Elizabeth McCracken, as you might expect), ultimately the theme is not strong enough to tie them all together and some seem like pieces the authors had lying around and couldn’t figure out what else to do with. Think about it this way: what story isn’t about romance and the decision to marry?

A few of the tales do put an interesting slant on this age-old storyline by positing a lesbian relationship for the protagonist or offering the possibility of same-sex marriage. Then there are the stories that engage directly with the plot and characters of Jane Eyre, giving Grace Poole’s (Helen Dunmore) or Mr. Rochester’s (Salley Vickers) side of things, putting Jane and Rochester in couples therapy (Francine Prose), or making Jane and Helen Burns part of a post-WWII Orphan Exchange (Audrey Niffenegger). My feeling with these spinoff stories was, I’m afraid, what’s the point? Plus there were a number of others that just felt tedious.

My least favorites were probably by Lionel Shriver (incredibly boring!), Kirsty Gunn (unrealistic, and she gives the name Mr. Rochester to a dog!) and Susan Hill (the title story, but she’s made it about Wallis Simpson – and has the audacity to admit, as if proudly, that she’s never read Jane Eyre!). On the other hand, one particular standout is by Elif Shafak. A Turkish Muslim falls in love with a visiting Dutch student but is so unfamiliar with romantic cues that she doesn’t realize he isn’t equally taken with her.

In Patricia Park’s story, my favorite of all, a Korean girl from Buenos Aires moves to New York City to study English. Park turns Jane Eyre on its head by having Teresa give up on the chance of romance to gain stability by marrying Juan, the St. John Rivers character. I loved getting a glimpse into a world I was entirely ignorant of – who knew there was major Korean settlement in Argentina? This also redoubled my wish to read Park’s novel, Re Jane. She’s working on a second novel set in Buenos Aires, so perhaps it will expand on this story.

The Bookbag reviews

Charlotte Brontë’s Secret Love by Jolien Janzing

by Jolien Janzing

Charlotte and Emily Brontë’s time in Belgium – specifically, Charlotte’s passion for her teacher, Constantin Heger – is the basis for this historical novel. The authoritative yet inviting narration is a highlight, but some readers may be uncomfortable with the erotic portrayal; it doesn’t seem to fit the historical record, which suggests an unrequited love affair.

Sanctuary by Robert Edric

by Robert Edric

Branwell Brontë narrates his final year of life, when alcoholism, mental illness and a sense of disgrace hounded him to despair. I felt I never came to understand Branwell’s inner life, beneath the decadence and all the feeling sorry for himself. This gives a sideways look at Charlotte, Emily and Anne, though the sisters are little more than critical voices here; none of them has a distinctive personality.

Mutable Passions : Charlotte Brontë: A Disquieting Affair by Philip Dent

: Charlotte Brontë: A Disquieting Affair by Philip Dent

Dent focuses on a short period in Charlotte Brontë’s life: with all her siblings dead and Villette near completion, a surprise romance with her father’s curate lends a brief taste of happiness. Given her repeated, vociferous denial of feelings for Mr. Nicholls, I had trouble believing that, just 20 pages later, his marriage proposal would provoke rapturous happiness. To put this into perspective, I felt Dent should have referenced the three other marriage proposals Brontë is known to have received. Overwritten and suited to readers of romance novels than to Brontë enthusiasts, this might work well as a play. Dent is better at writing individual scenes and dialogue than at providing context.

Two Abandonees

I had bad luck with these two novels, which both sounded incredibly promising but I eventually abandoned (along with Yuki Chan in Brontë Country, featured in last month’s Six Books I Abandoned Recently post):

Jane Steele by Lyndsay Faye

Jane Steele by Lyndsay Faye

Jane Steele is not quite Jane Eyre, though her life seems to mirror that of Brontë’s heroine in most particulars. How she differs is in her violent response to would-be sexual abusers. She’s a feminist vigilante wreaking vengeance on her enemies, whether her repulsive cousin or the vindictive master of “Lowan Bridge” (= Cowan Bridge, Brontë’s real-life school + Lowood, Jane Eyre’s). I stopped reading because I didn’t honestly think Faye was doing enough to set her book apart. “Reader, I murdered him” – nice spin-off line, but there wasn’t enough original material here to hold my attention. (Read the first 22%.)

The Madwoman Upstairs by Catherine Lowell

The Madwoman Upstairs by Catherine Lowell

There was every reason for me to love this novel – awkward American narrator, Oxford setting, Brontë connections aplenty, snarky literary criticism – but I got bored with it. Perhaps it was the first-person narration: being stuck in sarcastic Samantha Whipple’s head means none of the other characters feel real; they’re just paper dolls, with Orville a poor excuse for a Mr. Rochester substitute. I did laugh out loud a few times at Samantha’s unorthodox responses to classic literature (“Agnes Grey is, without question, the most boring book ever written”), but I gave up when I finally accepted that I had no interest in how the central mystery/treasure hunt played out. (Read the first 56%.)

An Excellent Biography

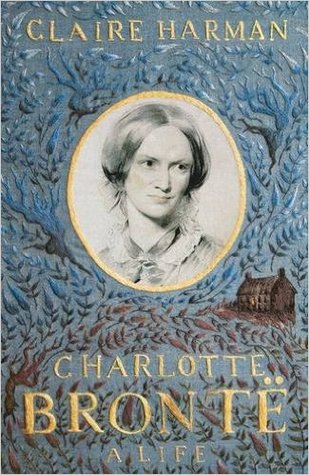

If I could recommend just one book from the recent flurry of Brontëana, it would be Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman, which I reviewed for For Books’ Sake back in November.

If I could recommend just one book from the recent flurry of Brontëana, it would be Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman, which I reviewed for For Books’ Sake back in November.

One of the things Harman’s wonderful biography does best is to trace how the Brontës’ childhood experiences found later expression in their fiction. A chapter on the publication of Jane Eyre (1847) is a highlight. Diehard fans might not encounter lots of new material, but Harman does make a revelation concerning Charlotte’s cause of death – not TB, as previously believed, but hyperemesis gravidarum, or extreme morning sickness. This will help you appreciate afresh the work of a “poet of suffering” whose novels were “all the more subversive because of [their] surface conventionality.” Interesting piece of trivia for you: this and the Janzing novel (above) open with the same scene from Charlotte’s time in Belgium.

If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma.

If you need to like a protagonist, expect frustration. Some of George’s behaviour is downright maddening, as when he obsessively plays his old Gameboy while his mother and Jenny pack up his childhood room. Tracing his relationships with his mother, his sister Cressida, and Jenny is rewarding. Sometimes they confront him over his shortcomings; other times they enable him. The novel is very funny, but it’s a biting, ironic humour, and there’s plenty of pathos as well. There are a few particular gut-punches, one relating to George’s father and others surrounding nice things he tries to do that backfire horribly. I thought of George as a rejoinder to all those ‘So-and-So Is Not Okay at All’ type of books featuring a face-planting woman on the cover. Greathead’s portrait is incisive but also loving. And yes, there is that hint of George, c’est moi recognition. His failings are all too common: the mildest of first-world tragedies but still enough to knock your confidence and make you question your purpose. For me this had something of the old-school charm of Jennifer Egan and Jonathan Safran Foer novels I read in the Naughties. I’ll seek out the author’s debut, Laura & Emma. The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection.

The family’s lies and secrets – also involving a Christmas run-in with Bruce’s shell-shocked brother decades ago – lead to everything coming to a head in a snowstorm. (As best I can tell, the 1995 setting was important mostly so there wouldn’t be cell phones during this crisis.) As with The Book of George, the episodic nature of the narrative means that particular moments are memorable but the whole maybe less so, and the interactions between characters stand out more than the people themselves. I’ll Come to You, named after a throwaway line in the text, is poorly served by both its cover and title, which give no sense of the contents. However, it’s a sweet, offbeat portrait of genuine, if generic, Americans; I was most reminded of J. Ryan Stradal’s work. Although I DNFed Kauffman’s The Gunners some years back, I’d be interested in trying her again with Chorus, which sounds like another linked story collection. Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.)

Mills and Shaw consider the same fundamental issues: bi erasure, with bisexuality the least understood and most easily overlooked element of LGBT and many passing as straight if in heterosexual marriages; and the stereotype of bis as hypersexual or promiscuous. Mills is keen to stress that bisexuals have very different trajectories and phases. Like Wilde, they might have a heterosexual era of happy marriage and parenthood followed by a homosexual spree. Or they might have simultaneous lovers of multiple genders. Some might never even act on strong same-sex desires. (Late last year I encountered a similar unity-in-diversity approach in Daniel Tamet’s Nine Minds, a group biography about autistic people.) I’ve also read Watts’

I’ve also read Watts’

Seamus is the subject of the opening title story and “Gorgon’s Head,” so he felt to me like the core of the novel and I would happily have had him as the protagonist throughout. He’s a spiky would-be poet who ends up offending his classmates with his snobby opinions (“her poems were, in the words of a fictional Robert Lowell in an Elizabeth Bishop biopic, ‘observations broken into lines’ … she lacked a poetic intelligence”) and funds his studies by working in the kitchen at a hospice, where he meets a rough local named Bert and they have a sexual encounter that shades into cruelty.

Seamus is the subject of the opening title story and “Gorgon’s Head,” so he felt to me like the core of the novel and I would happily have had him as the protagonist throughout. He’s a spiky would-be poet who ends up offending his classmates with his snobby opinions (“her poems were, in the words of a fictional Robert Lowell in an Elizabeth Bishop biopic, ‘observations broken into lines’ … she lacked a poetic intelligence”) and funds his studies by working in the kitchen at a hospice, where he meets a rough local named Bert and they have a sexual encounter that shades into cruelty. I discovered Grace Nichols a few years ago when I reviewed Passport to Here and There for Wasafiri. One of “Five Gold Reads” to mark Virago’s 50th anniversary, this was the Guyanese-British poet’s second collection (the reissue also includes a few poems from her first book, I Is a Long-Memoried Woman).

I discovered Grace Nichols a few years ago when I reviewed Passport to Here and There for Wasafiri. One of “Five Gold Reads” to mark Virago’s 50th anniversary, this was the Guyanese-British poet’s second collection (the reissue also includes a few poems from her first book, I Is a Long-Memoried Woman).

I picked this up expecting a cute cat tale for children, only realizing afterwards that it’s considered horror. When a grey kitten wanders into their garden, Davy is less enamoured than the rest of the Burrell family. His suspicion mounts as the creature starts holding court in the lounge, expecting lavish meals and attention at all times. His parents and sister seem to be under the cat’s spell in some way, and it’s growing much faster than any young animal should. Davy and his pal George decide to do something about it. Since I’m a cat owner, I’m not big into evil cat stories (e.g., Cat out of Hell by Lynne Truss), and this one was so short as to feel underdeveloped.

I picked this up expecting a cute cat tale for children, only realizing afterwards that it’s considered horror. When a grey kitten wanders into their garden, Davy is less enamoured than the rest of the Burrell family. His suspicion mounts as the creature starts holding court in the lounge, expecting lavish meals and attention at all times. His parents and sister seem to be under the cat’s spell in some way, and it’s growing much faster than any young animal should. Davy and his pal George decide to do something about it. Since I’m a cat owner, I’m not big into evil cat stories (e.g., Cat out of Hell by Lynne Truss), and this one was so short as to feel underdeveloped.  “The Old Nurse’s Story” by Elizabeth Gaskell (1852)

“The Old Nurse’s Story” by Elizabeth Gaskell (1852) The unnamed narrator is a disgraced teacher who leaves London for a rental cottage on the Hare House estate in Galloway. Her landlord, Grant Henderson, and his rebellious teenage sister, Cass, are still reeling from the untimely death of their brother. The narrator gets caught up in their lives even though her shrewish neighbour warns her not to. There was a lot that I loved about the atmosphere of this one: the southwest Scotland setting; the slow turn of the seasons as the narrator cycles around the narrow lanes and finds it getting dark earlier, and cold; the inclusion of shape-shifting and enchantment myths; the creepy taxidermy up at the manor house; and the peculiar fainting girls/mass hysteria episode that precipitated the narrator’s banishment and complicates her relationship with Cass. The further you get, the more unreliable you realize this narrator is, yet you keep rooting for her. There are a few too many set pieces involving dead animals, and, overall, perhaps more supernatural influences than are fully explored, but I liked Hinchcliffe’s writing enough to look out for what else she will write. (Readalikes:

The unnamed narrator is a disgraced teacher who leaves London for a rental cottage on the Hare House estate in Galloway. Her landlord, Grant Henderson, and his rebellious teenage sister, Cass, are still reeling from the untimely death of their brother. The narrator gets caught up in their lives even though her shrewish neighbour warns her not to. There was a lot that I loved about the atmosphere of this one: the southwest Scotland setting; the slow turn of the seasons as the narrator cycles around the narrow lanes and finds it getting dark earlier, and cold; the inclusion of shape-shifting and enchantment myths; the creepy taxidermy up at the manor house; and the peculiar fainting girls/mass hysteria episode that precipitated the narrator’s banishment and complicates her relationship with Cass. The further you get, the more unreliable you realize this narrator is, yet you keep rooting for her. There are a few too many set pieces involving dead animals, and, overall, perhaps more supernatural influences than are fully explored, but I liked Hinchcliffe’s writing enough to look out for what else she will write. (Readalikes:  Ever since I read

Ever since I read  .

. Basics: 11 stories, grouped under 4 mythical locales

Basics: 11 stories, grouped under 4 mythical locales Basics: 8 linked stories following 7th-grade teacher Beatrice Hempel through her twenties and thirties

Basics: 8 linked stories following 7th-grade teacher Beatrice Hempel through her twenties and thirties Basics: 18 stories, some of flash fiction length

Basics: 18 stories, some of flash fiction length

#1 The main character’s sweet nickname takes me to Sugar and Other Stories by A.S. Byatt. Byatt is my favourite author. Rereading her

#1 The main character’s sweet nickname takes me to Sugar and Other Stories by A.S. Byatt. Byatt is my favourite author. Rereading her  #2 The title of that memorable story takes me to

#2 The title of that memorable story takes me to  #3 According to a search of my Goodreads library, the only other book I’ve ever read by a Miranda is A Girl Walks into a Book by Miranda K. Pennington, a charming bibliomemoir about the lives and works of the Brontës. I especially enjoyed the cynical dissection of Wuthering Heights, a classic I’ve never managed to warm to.

#3 According to a search of my Goodreads library, the only other book I’ve ever read by a Miranda is A Girl Walks into a Book by Miranda K. Pennington, a charming bibliomemoir about the lives and works of the Brontës. I especially enjoyed the cynical dissection of Wuthering Heights, a classic I’ve never managed to warm to. #4 From one famous set of sisters in the arts to another with Vanessa and Her Sister by Priya Parmar, a novel about Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf. It is presented as Vanessa’s diary, incorporating letters and telegrams. The interactions with their Bloomsbury set are delightful, and sibling rivalry is a perennial theme I can’t resist.

#4 From one famous set of sisters in the arts to another with Vanessa and Her Sister by Priya Parmar, a novel about Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf. It is presented as Vanessa’s diary, incorporating letters and telegrams. The interactions with their Bloomsbury set are delightful, and sibling rivalry is a perennial theme I can’t resist. #5 Another Vanessa novel and one I would highly recommend to anyone wanting a nuanced look at the #MeToo phenomenon is My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell. It’s utterly immersive and as good a first-person narrative as anything Curtis Sittenfeld has ever written. I also appreciated the allusions to other works of literature, from Nabokov (the title is from Pale Fire) to Swift. This would make a great book club selection.

#5 Another Vanessa novel and one I would highly recommend to anyone wanting a nuanced look at the #MeToo phenomenon is My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell. It’s utterly immersive and as good a first-person narrative as anything Curtis Sittenfeld has ever written. I also appreciated the allusions to other works of literature, from Nabokov (the title is from Pale Fire) to Swift. This would make a great book club selection. #6 Speaking of feminist responses to #MeToo, Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo is just as good as you’ve heard. If you haven’t read it yet, why not? It’s a linked short story collection about 12 black women navigating twentieth-century and contemporary Britain – balancing external and internal expectations to build lives of their own. It reads like poetry.

#6 Speaking of feminist responses to #MeToo, Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo is just as good as you’ve heard. If you haven’t read it yet, why not? It’s a linked short story collection about 12 black women navigating twentieth-century and contemporary Britain – balancing external and internal expectations to build lives of their own. It reads like poetry.