I Spy TBR Challenge

I spotted this recently on Ex Urbanis and it was too fun to pass up. (I believe the meme started on YouTube, but I’ve been unable to trace the chain back to the very beginning.) There are 20 categories; for each one choose at least one title or cover that fits in some way.

I decided to limit myself to books on my to-read shelves, but had to cheat for two categories and pick books I’ve already read. Some were so easy I could have picked out at least 5–10 books that fit the bill, while others were quite a challenge.

The idea is to gather up all the books within five minutes, but because I had to go up and down the stairs and survey shelves in multiple rooms it took me just over 15! See how fast you can find something for each prompt.

Food

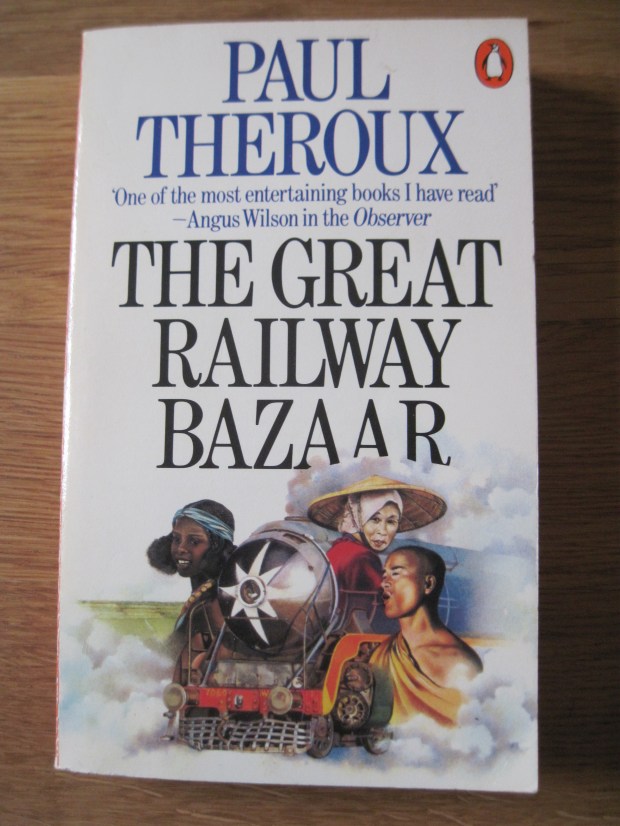

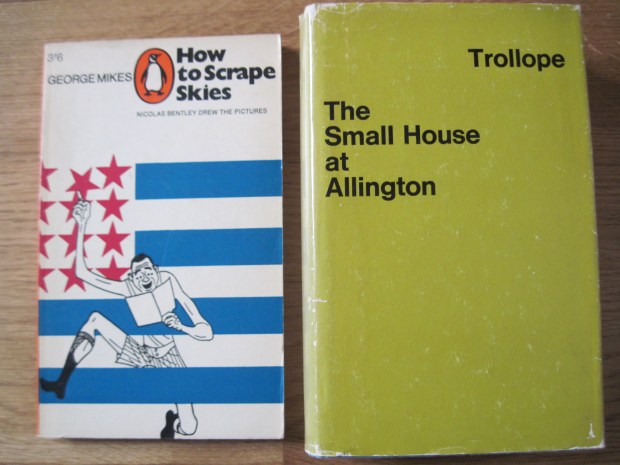

Transport

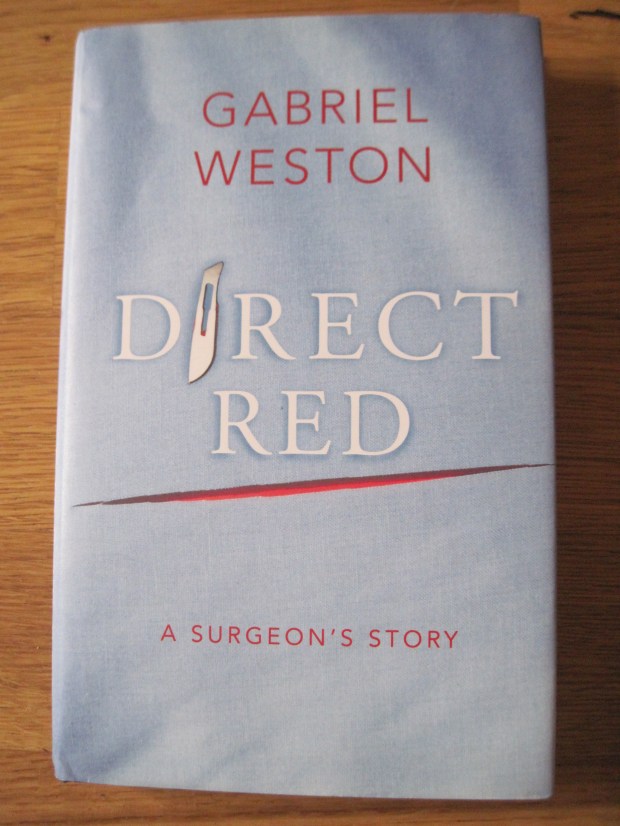

Weapon – This one was really tough, since I don’t read crime fiction. But I finally managed to find a surgeon’s memoir with a scalpel on the cover.

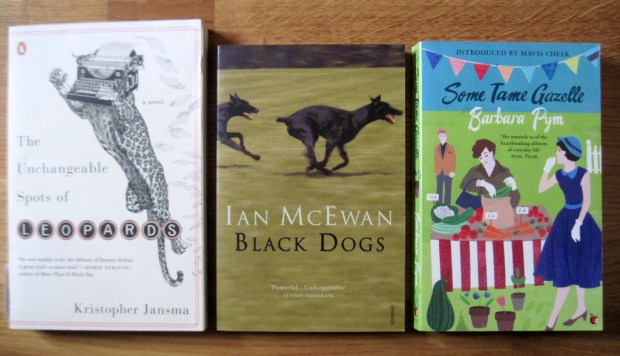

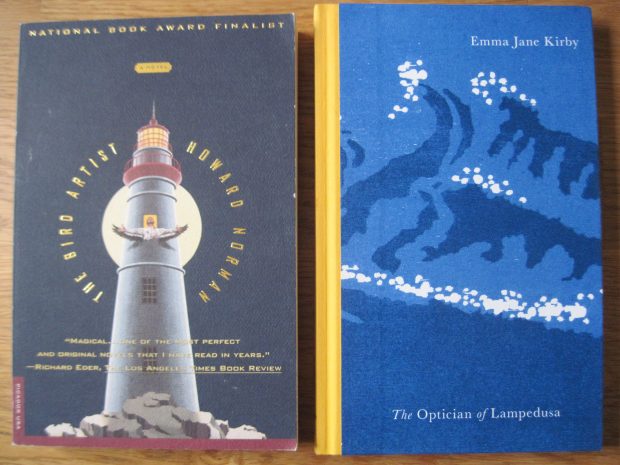

Animal – I could easily have found 15+ for this one, thanks to my husband’s nature books, but I stuck with fiction.

Number

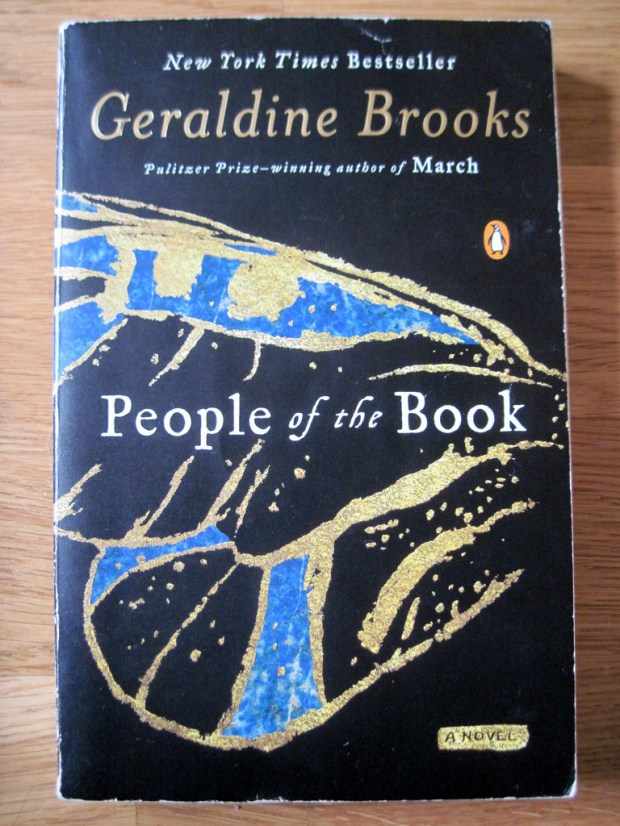

Something You Read

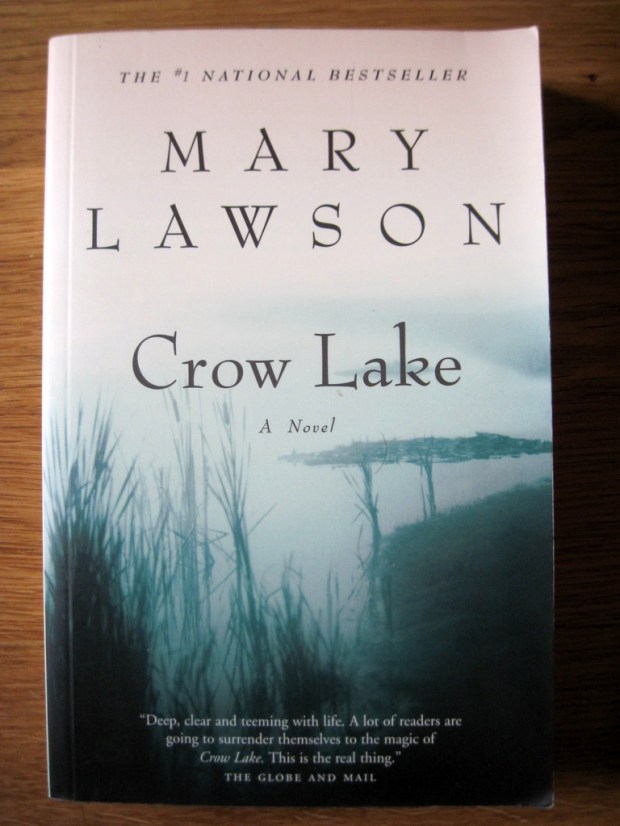

Body of Water

Product of Fire – Another really difficult one, so I cheated with this May Sarton memoir I’ve already read.

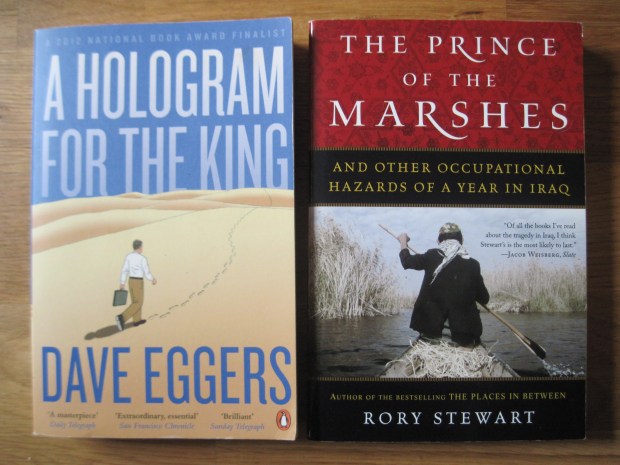

Royalty

Architecture

Clothing – Another cheat of sorts: all I could find was the cover of Bill Bryson’s memoir, which I’ve already read.

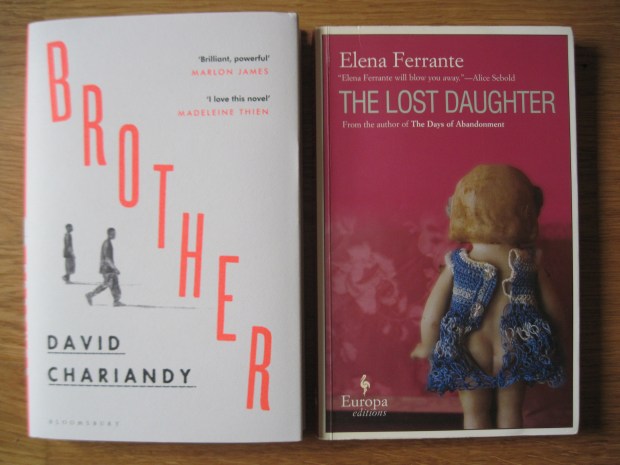

Family Member

Time of Day

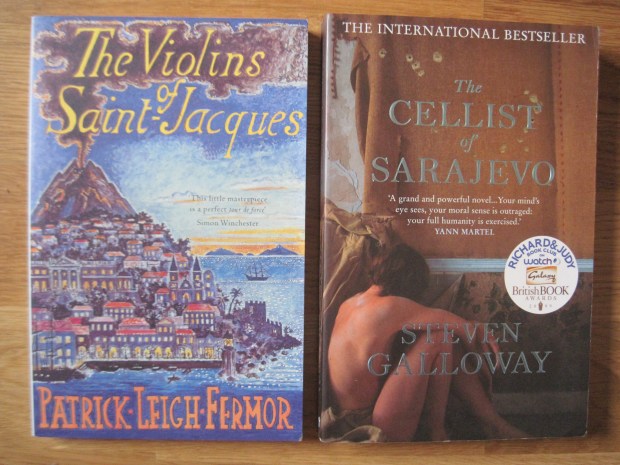

Music

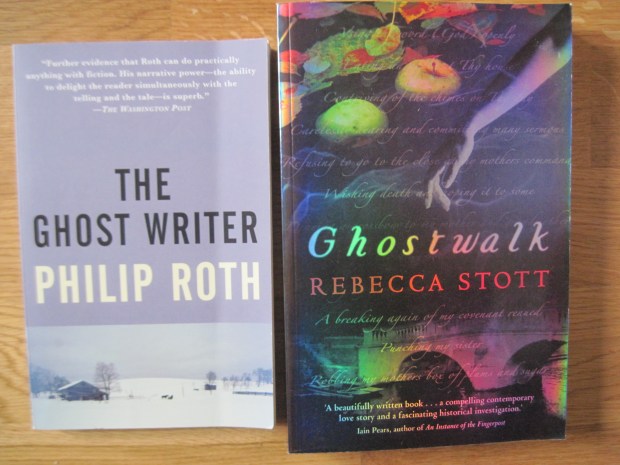

Paranormal Being

Occupation

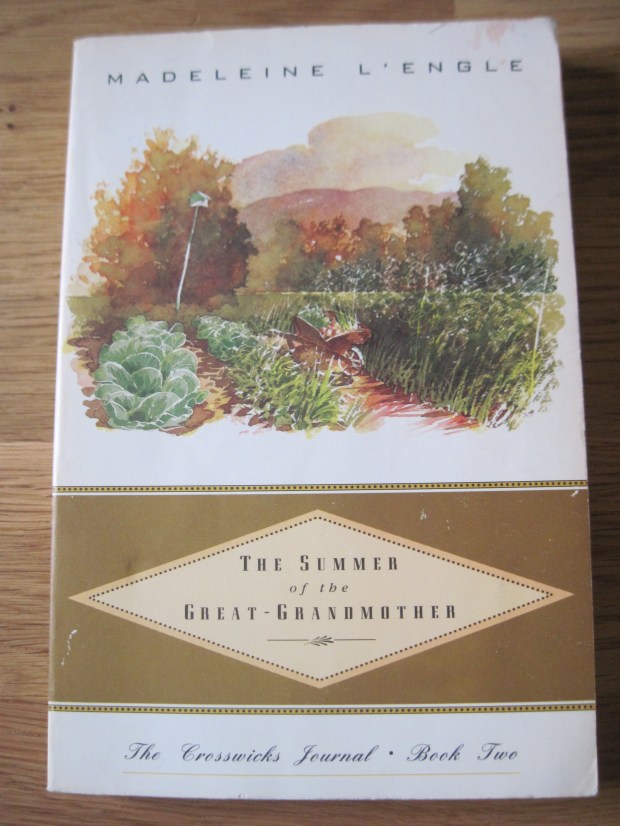

Season

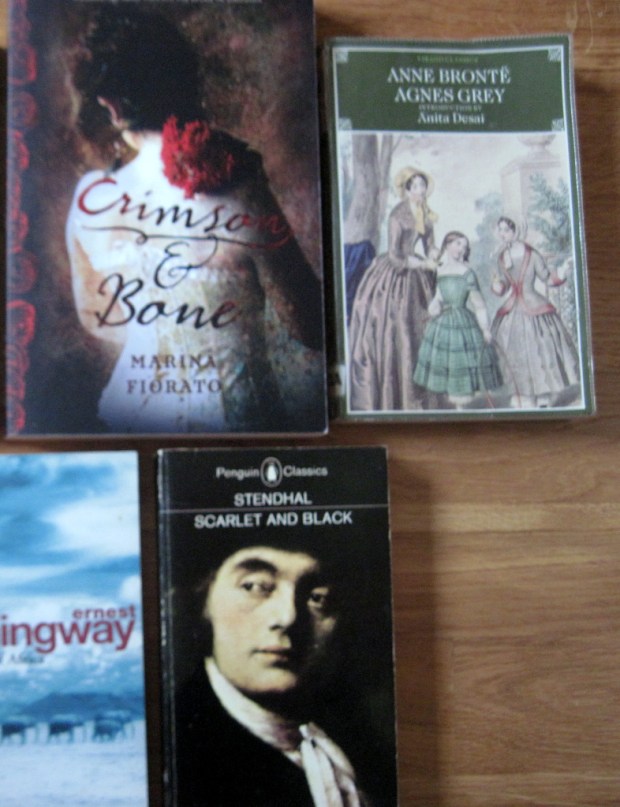

Color – Another one I could have amassed tons for. (Partially cut off is Ernest Hemingway’s Green Hills of Africa.)

Celestial Body

Something that Grows

Blog Tour: The Secret Life of Mrs. London by Rebecca Rosenberg

I have a weakness for novels about history’s famous wives, whether that’s Zelda Fitzgerald, the multiple Mrs. Hemingways, or the First Ladies of the U.S. presidents. A valuable addition to that delightful sub-genre of fiction is The Secret Life of Mrs. London, the recent debut novel by California lavender farmer Rebecca Rosenberg. I’m pleased to be closing out the blog tour today with a mini review. So many thorough reviews have already appeared that I won’t attempt to compete with them, but will just share a few reasons why I found this a worthwhile read.

I have a weakness for novels about history’s famous wives, whether that’s Zelda Fitzgerald, the multiple Mrs. Hemingways, or the First Ladies of the U.S. presidents. A valuable addition to that delightful sub-genre of fiction is The Secret Life of Mrs. London, the recent debut novel by California lavender farmer Rebecca Rosenberg. I’m pleased to be closing out the blog tour today with a mini review. So many thorough reviews have already appeared that I won’t attempt to compete with them, but will just share a few reasons why I found this a worthwhile read.

Set in 1915 to 1917, this is the story of the last couple of years of Jack London’s life, narrated by his second wife, Charmian, who was five years his senior. The novel opens in California at the Londons’ Beauty Ranch and Wolf House complex and also travels to Hawaii and New York City. Events are condensed and fictionalized, but true to life – thanks to the biography Charmian wrote of Jack and the author’s access to her journals and their letters.

Here are a few things I particularly liked about the novel:

A fantastic opening scene: September 1915: Charmian decides to fix Jack’s hangover with strong coffee and a boxing match – with her! – while their Japanese servant, Nakata, and their house guests look on with bemusement. “Nothing breathes vigor into a marriage like a boxing match.”

A fantastic opening scene: September 1915: Charmian decides to fix Jack’s hangover with strong coffee and a boxing match – with her! – while their Japanese servant, Nakata, and their house guests look on with bemusement. “Nothing breathes vigor into a marriage like a boxing match.”- A glimpse into Jack London’s lesser-known writings: I’ve only ever read White Fang and The Call of the Wild, as a child. But in addition to his adventure stories he also wrote realist/sociopolitical novels and science fiction. At the time when the novel opens, he’s working on The Star Rover. This has inspired me to look into some of his more obscure work.

- The occasional clash of the spouses’ ambitions: Charmian considers it her duty to hold Jack to his promise of writing 1,000 words a day. However, she is an aspiring writer herself, and she often needles Jack to talk to his publisher about accepting her books. (She eventually published two travel books, The Log of the Snark (1915), about their years sailing the Pacific, and Our Hawaii (1917), as well as her biography of her late husband, The Book of Jack London, in 1921.)

- Charmian’s longing for motherhood: Jack London had an ex-wife and two daughters, Joan and Becky. In 1910 Charmian gave birth to a daughter, Joy, who soon died. Even though she is 43 by the time the book opens, she still wants to try again for a baby. Her hopes and disappointments are a poignant part of the story.

- Cameos from other historical figures: Harry Houdini and his wife, especially, have a large part to play in the novel, particularly in the last quarter.

I wasn’t so keen on the sex scenes, which are fairly frequent. However, I can recommend this to fans of Nancy Horan’s work.

My rating:

The Secret Life of Mrs. London was published by Lake Union Publishing on January 30th. I read an e-copy via NetGalley.

Literary Blind Spots: Hemingway and Fitzgerald

Despite being educated through university level in the United States, I’m better acquainted with British literature than American, in part due to my own predilections. Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald are two of the American authors I’ve most struggled with. For one thing, their novels’ titles are interchangeable, abstract quotations that I can never keep straight. Which is which? The Sun Also Rises is the bullfighting one, right? And is A Farewell to Arms the other one I’ve read? Fitzgerald is an even worse offender as titles go, with The Great Gatsby the only one that actually refers to its contents.

Despite being educated through university level in the United States, I’m better acquainted with British literature than American, in part due to my own predilections. Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald are two of the American authors I’ve most struggled with. For one thing, their novels’ titles are interchangeable, abstract quotations that I can never keep straight. Which is which? The Sun Also Rises is the bullfighting one, right? And is A Farewell to Arms the other one I’ve read? Fitzgerald is an even worse offender as titles go, with The Great Gatsby the only one that actually refers to its contents.

For the record, I recognize The Great Gatsby as a masterpiece, and I absolutely loved A Moveable Feast, Hemingway’s memoir of life in Paris. I also enjoy reading about the Hemingways (Paula McLain’s The Paris Wife and Naomi Wood’s Mrs. Hemingway) and the Fitzgeralds (Therese Anne Fowler’s Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald and R. Clifton Spargo’s Beautiful Fools). But when I’ve tried to go deeper into the authors’ work, it hasn’t been an unmitigated success. The above two Hemingway novels are just okay for me. The Sun Also Rises struck me as having a thin plot, two-dimensional characters and repetitious dialogue.

For the record, I recognize The Great Gatsby as a masterpiece, and I absolutely loved A Moveable Feast, Hemingway’s memoir of life in Paris. I also enjoy reading about the Hemingways (Paula McLain’s The Paris Wife and Naomi Wood’s Mrs. Hemingway) and the Fitzgeralds (Therese Anne Fowler’s Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald and R. Clifton Spargo’s Beautiful Fools). But when I’ve tried to go deeper into the authors’ work, it hasn’t been an unmitigated success. The above two Hemingway novels are just okay for me. The Sun Also Rises struck me as having a thin plot, two-dimensional characters and repetitious dialogue.

When I eagerly approached Tender Is the Night last year – having recently read a novel about the real-life couple who inspired Fitzgerald’s portrait of Dick and Nicole Diver, Gerald and Sara Murphy (Villa America by Liza Klaussmann) – I pulled out a lot of great individual lines but had trouble following the basic plot and only really enjoyed the early chapters of Book Two. Here are some of those pearls of prose:

The delight in Nicole’s face—to be a feather again instead of a plummet, to float and not to drag. She was a carnival to watch—at times primly coy, posing, grimacing and gesturing—sometimes the shadow fell and the dignity of old suffering flowed down into her finger tips.

somehow Dick and Nicole had become one and equal, not apposite and complementary; she was Dick too, the drought in the marrow of his bones. He could not watch her disintegrations without participating in them.

Well, you never knew exactly how much space you occupied in people’s lives.

women marry all their husbands’ talents and naturally, afterwards, are not so impressed with them as they may keep up the pretense of being.

Imagine my surprise when I learned from a note at the end of my Penguin paperback that Fitzgerald made a major revision that rearranged the action into chronological order, thus opening with Book Two. That text, edited by Malcolm Cowley, appeared in 1951 and was printed by Penguin from 1955. However, the version I have – as reprinted from 1982 onwards – goes back to Fitzgerald’s first edition. Would I have had a more favorable reaction to the novel if I’d encountered it in its revised version? Somehow I think so.

Is there a Hemingway or Fitzgerald novel that will change my opinion about these literary lions? Share your favorites.

I Do Love a Good Book List

In the same way that I love following literary prize races (see my post on that topic from a couple weeks ago), I adore a good book list. This includes everything from an inspirational lifetime reading menu such as 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die to those gimmicky “5 Novels About…” or “10 Books for People Who Like…” lists you get on websites like BuzzFeed and the Huffington Post.

Every time a new ‘Best Books Ever’ type of checklist comes out, I gleefully scan through to figure out how many I’ve already read. Usually the disappointing results smack me back and remind me that for all my voracious reading, I still haven’t read many of the classics everyone’s supposed to have read by my age.

Here for your delectation (if you like this sort of thing) is a sampling of the book lists I’ve bookmarked over the years, with my running total noted in brackets after each:

THE BEST OF THE BEST

The 100 Greatest Novels of All Time, as chosen by the Guardian in 2003 [33]

1000 novels everyone must read, as chosen by the Guardian in 2009 (interestingly, they divide it up by genre: Love Stories, Crime Fiction, Comedy, Family & Self, State of the Nation, Science Fiction & Fantasy, and War & Travel) [155 + 2 in progress]

The 100 greatest non-fiction books, as chosen by the Guardian in 2011 [7]

Vintage 21, a set of 21 modern classics chosen in 2011 [14]

100 novels everyone should read, as chosen by the Telegraph in April [29]

The 100 best novels written in English, as chosen by Robert McCrum in the Guardian last week [34]

PARTICULAR TIMES OF LIFE

65 Books You Need To Read in Your 20s, from BuzzFeed (alas, it’s too late for many of us) [13, 12 of which I think I read in my 20s]

25 Books to Help You Survive Your Mid-20s, from Bustle (ditto) [9, all read in my 20s, I think]

Conversely, here’s 15 Books You Should Definitely Not Read in Your 20s from Flavorwire (well, that’s alright, then) [I disobeyed them on 4 counts]

21 Books Every Woman Should Read By 35, from Bustle (I’ve got 3.13 years to work on it) [5; I left The Flamethrowers unfinished]

11 Novels That Expectant Parents Should Read Instead of Parenting Books, from Electric Literature (my mother may be reading this, so I must hastily add that THIS SITUATION DOES NOT APPLY TO ME!) [6]

SPECIFIC AUTHORS

The Best Hemingway Novels, on Publishers Weekly [2 out of 6, but A Moveable Feast is my favorite from him]

The 13 Best John Steinbeck Books, on Publishers Weekly [3]

The 10 Best Mark Twain Books, on Publishers Weekly [just 1!]

23 Contemporary Writers You Should Have Read by Now, on Reader’s Digest [I’ve read 3, Elizabeth Spencer, Percival Everett and Pamela Erens]

Beyond Murakami: 7 Japanese Authors to Read, on Book Riot [none so far]

SPECIFIC GENRES

20 Classic Novels You’ve Never Heard of, from QwikLit [I’ve heard of plenty of these, but only read 1]

12 Fiction Books That Will Shape Your Theology, from RELEVANT Magazine [3]

The 10 Best Books Shorter Than 150 Pages, on Publishers Weekly [2]

10 Best Southern Gothic Books, on Publishers Weekly [none so far]

10 Novels with Multiple Narratives, on Publishers Weekly [2]

The 10 Best Short Story Collections You’ve Never Read, on Publishers Weekly [they got that right; none so far]

The top 10 novels about childbirth, on the Guardian (again, NOT APPLICABLE TO ME!) [7]

I also highly recommend Nancy Pearl’s Book Lust series of four books, each one divided into themes.

ONE LAST LIST

Not a book list, but it may be useful for all you bibliophiles:

The 25 Best Websites for Literature Lovers, by Flavorwire

Do you love book lists as much as I do? Are you addicted to counting how many you’ve read from a checklist?

How do you fare on the lists above?

Review: The House of Hawthorne by Erika Robuck

We often resent books we’re forced to read in school, but The Scarlet Letter wasn’t like that for me. Even though it was assigned reading for high school, I could instantly sense how important it was in the history of American literature. The tragic story of Hester Prynne and her judgmental community is one that stays with me half a lifetime later. I reread it in college for a Hawthorne & Melville course, for which I also read The Blithedale Romance, The House of the Seven Gables, and several of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s best short stories.

We often resent books we’re forced to read in school, but The Scarlet Letter wasn’t like that for me. Even though it was assigned reading for high school, I could instantly sense how important it was in the history of American literature. The tragic story of Hester Prynne and her judgmental community is one that stays with me half a lifetime later. I reread it in college for a Hawthorne & Melville course, for which I also read The Blithedale Romance, The House of the Seven Gables, and several of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s best short stories.

My more-than-average interest in Hawthorne, combined with my love of historical fiction about “famous wives” (see my BookTrib articles on the subject, including one specifically about the Hemingway and Fitzgerald wives) meant that I was eager to read Erika Robuck’s latest. She’s made a name for herself with novels about some of history’s famous women, including Zelda Fitzgerald, Edna St. Vincent Millay and one of the Hemingway wives, but somehow I’ve never read anything by her until now.

“Time flies over us, but leaves its shadow behind.”

(one of Robuck’s epigraphs, from Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun)

The novel is from the first-person perspective of Sophia Peabody, later the wife of Nathaniel Hawthorne. The Peabodys were an artistic, intellectual family who encouraged Sophia to cultivate her talent as a painter and sculptor, but illness often held her back: she suffered from debilitating headaches and turned to morphine and mesmerism for relief. The story begins and ends in the spring of 1864, when Nathaniel, suffering from a stomach ailment, sets off on a final journey without Sophia. In between these bookends, the novel spans the 1830s through the 1860s, taking in Sophia’s sojourn in Cuba as a young woman, her and Nathaniel’s courtship, and the challenges of parenthood and making a living from art.

My favorite portions of the novel were set in Concord, Massachusetts, that haven for writers and Transcendentalists. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Herman Melville all play minor roles. It’s especially amusing to see Melville, Hawthorne’s ardent admirer, overstep the boundaries of polite society and become an irksome stalker. What I did not realize from previous biographical reading about the Hawthornes is that they nearly always struggled for money. They rented Emerson’s uncle’s house in Concord but were evicted when they fumbled to make payments. Nathaniel’s jobs in the Custom House and as the U.S. Consul in Liverpool (appointed by President Franklin Pierce, who was a personal friend and whose biography he wrote) were undertaken out of financial desperation rather than interest.

The Hawthornes’ time in Europe was another highlight of the novel for me. They encounter the Brownings and finally get a chance to see all the Italian art that has inspired Sophia over the years. Their oldest daughter, Una, also falls ill with malaria, which provides some great dramatic scenes in later chapters. I warmed to this late vision of Sophia as a devoted mother, whereas I struggled to accept her as a vibrant young woman and a randy wife. Her constant complaints about headaches are annoying, and I wasn’t convinced that the Cuba chapters were relevant to the novel as a whole; Robuck tries to link Sophia’s observations of slavery there with the abolitionist sentiments of the 1860s, but Sophia’s devotion to the antislavery cause was only ever half-hearted, so I didn’t believe the experience in Cuba could have affected her that deeply. Her unconsummated lust for Fernando is also, I suppose, meant to prefigure her abiding passion for Nathaniel – which is described in frequent, cringe-worthy sex scenes and flowery lines like “In his gaze, I feel our souls rise up to meet each other.”

Ultimately, my disconnection from Sophia as narrator meant that I would prefer to read about the Hawthornes in biographies, of which there are plenty. Two novels I would recommend that incorporate many of the same historical figures are Miss Fuller by April Bernard and What Is Visible by Kimberly Elkins (about the deaf-blind Laura Bridgman – who has a tiny cameo here). Beautiful Fools by R. Clifton Spargo uses a Cuba setting to better effect in telling the story of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald’s last holiday. I preferred all three of these to The House of Hawthorne. However, I’m certainly up for trying more of Robuck’s fiction.

I received early access to this book through the Penguin First to Read program.

You Are Having a Good Time: Stories by Amie Barrodale

You Are Having a Good Time: Stories by Amie Barrodale

Sweet Home by Carys Bray

Sweet Home by Carys Bray

Parfums: A Catalogue of Remembered Smells by Philippe Claudel

Parfums: A Catalogue of Remembered Smells by Philippe Claudel  Absalom’s Daughters by Suzanne Feldman

Absalom’s Daughters by Suzanne Feldman

The Hemingway Thief by Shaun Harris

The Hemingway Thief by Shaun Harris Setting Free the Bears by John Irving

Setting Free the Bears by John Irving