Blog Tour: Literary Landscapes, edited by John Sutherland

The sense of place can be a major factor in a book’s success – did you know there is a whole literary prize devoted to just this? (The Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize, “for a distinguished work of fiction, non-fiction or poetry, evoking the spirit of a place.”) No matter when or where a story is set, an author can bring it to life through authentic details that appeal to all the senses, making you feel like you’re on Prince Edward Island or in the Gaudarrama Mountains even if you’ve never visited Atlantic Canada or central Spain. The 75 essays of Literary Landscapes, a follow-up volume to 2016’s celebrated Literary Wonderlands, illuminate the real-life settings of fiction from Jane Austen’s time to today. Maps, author and cover images, period and modern photographs, and other full-color illustrations abound.

The sense of place can be a major factor in a book’s success – did you know there is a whole literary prize devoted to just this? (The Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize, “for a distinguished work of fiction, non-fiction or poetry, evoking the spirit of a place.”) No matter when or where a story is set, an author can bring it to life through authentic details that appeal to all the senses, making you feel like you’re on Prince Edward Island or in the Gaudarrama Mountains even if you’ve never visited Atlantic Canada or central Spain. The 75 essays of Literary Landscapes, a follow-up volume to 2016’s celebrated Literary Wonderlands, illuminate the real-life settings of fiction from Jane Austen’s time to today. Maps, author and cover images, period and modern photographs, and other full-color illustrations abound.

Each essay serves as a compact introduction to a literary work, incorporating biographical information about the author, useful background and context on the book’s publication, and observations on the geographical location as it is presented in the story – often through a set of direct quotations. (Because each work is considered as a whole, you may come across spoilers, so keep that in mind before you set out to read an essay about a classic you haven’t read but still intend to.) The authors profiled range from Mark Twain to Yukio Mishima and from Willa Cather to Elena Ferrante. A few of the world’s great cities appear in multiple essays, though New York City as variously depicted by Edith Wharton, Jay McInerney and Francis Spufford is so different as to be almost unrecognizable as the same place.

One of my favorite pieces is on Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. “Dickens was not interested in writing a literary tourist’s guide,” it explains; “He was using the city as a metaphor for how the human condition could, unattended, go wrong.” I also particularly enjoyed those on Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped. The fact that I used to live in Woking gave me a special appreciation for the essay on H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, “a novel that takes the known landscape and, brilliantly, estranges it.” The two novels I’ve been most inspired to read are Thomas Wharton’s Icefields (1995; set in Jasper, Alberta) and Kate Grenville’s The Secret River (2005; set in New South Wales).

The essays vary subtly in terms of length and depth, with some focusing on plot and themes and others thinking more about the author’s experiences and geographical referents. They were contributed by academics, writers and critics, some of whom were familiar names for me – including Nicholas Lezard, Robert Macfarlane, Laura Miller, Tim Parks and Adam Roberts. My main gripe about the book would be that the individual essays have no bylines, so to find out who wrote a certain one you have to flick to the back and skim through all the contributor biographies until you spot the book in question. There are also a few more typos than I tend to expect from a finished book from a traditional press (e.g. “Lady Deadlock” in the Bleak House essay!). Still, it is a beautifully produced, richly informative tome that should make it onto many a Christmas wish list this year; it would make an especially suitable gift for a young person heading off to study English at university. It’s one to have for reference and dip into when you want to be inspired to discover a new place via an armchair visit.

Literary Landscapes will be published by Modern Books on Thursday, October 25th. My thanks to Alison Menzies for arranging my free copy for review.

My (Tiny) Collection of Signed Copies

The other day I discovered a pencil-written recipe in the back of a secondhand book I got for Christmas. It got me thinking about handwriting in books: signatures, inscriptions, previous owners’ names, marginalia, and so on. If I can find enough examples of all those in my personal library, I might turn this into a low-key series. For now, though, I’ve rounded up my signed copies for a little photo gallery.

I’ve never placed particular value on owning signed copies of books. I’m just as likely to resell a signed book or give it away to a friend as I am a standard copy. The signed books I do have on my shelves are usually a result of having gone to an author event and figuring I may as well stick around for the signing. A few were totally accidental in secondhand purchases.

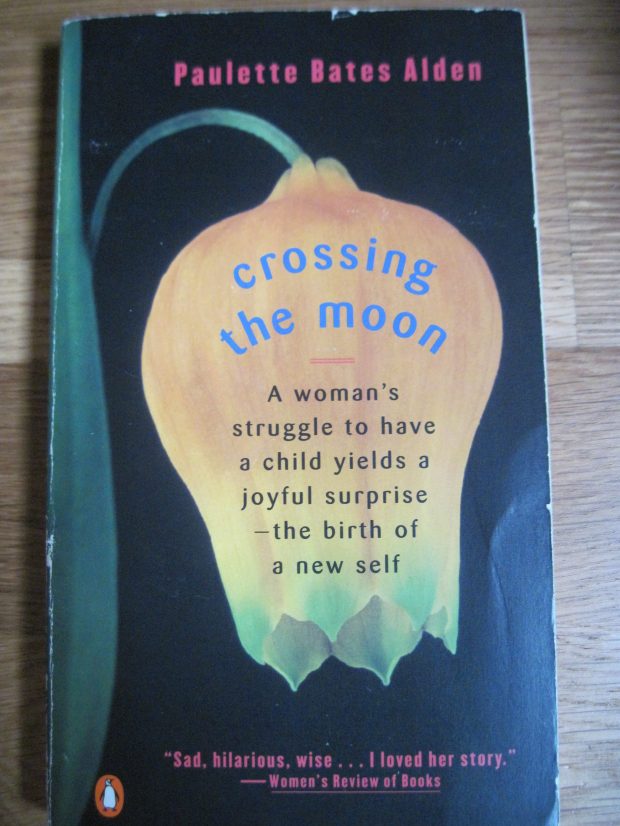

Though I’ve had personal correspondence with Paulette Bates Alden and love the three books of hers that I’ve read, this signature is entirely coincidental, in a used copy from Amazon. Shame on Patti for getting rid of it after Paulette’s book club visit in 2000!

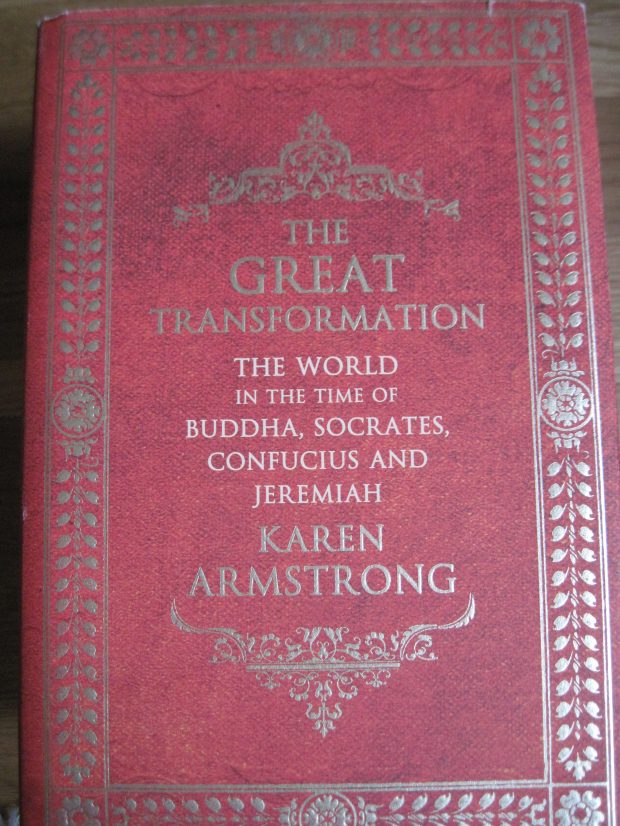

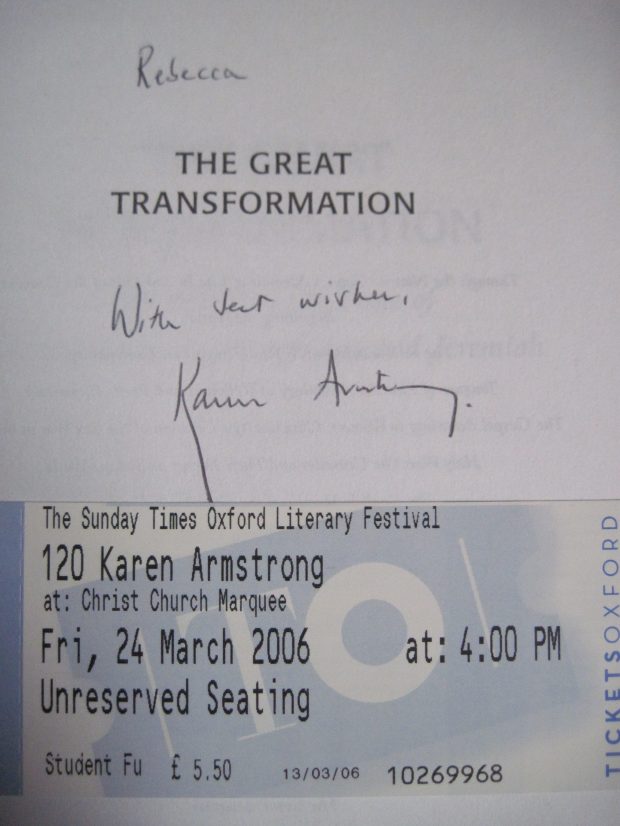

I love Karen Armstrong’s work, especially her two memoirs about deciding not to be a nun, and A History of God. I’ve seen her speak twice and am always impressed by her clear reasoning. (Tell you a secret, though: I couldn’t get through this particular book.)

While my husband worked at Royal Holloway we saw Alain de Botton speak at the Runnymede Literary Festival and I had him sign a copy of my favorite of his books.

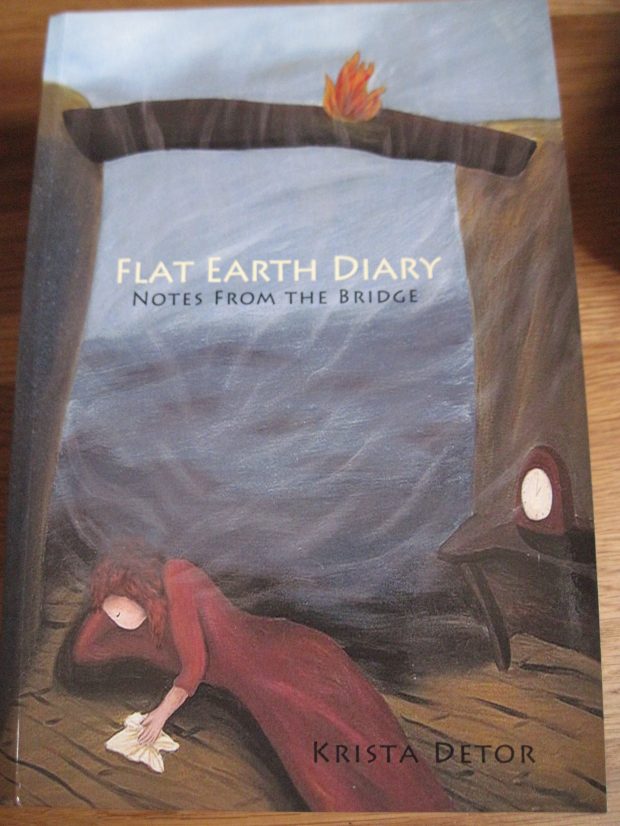

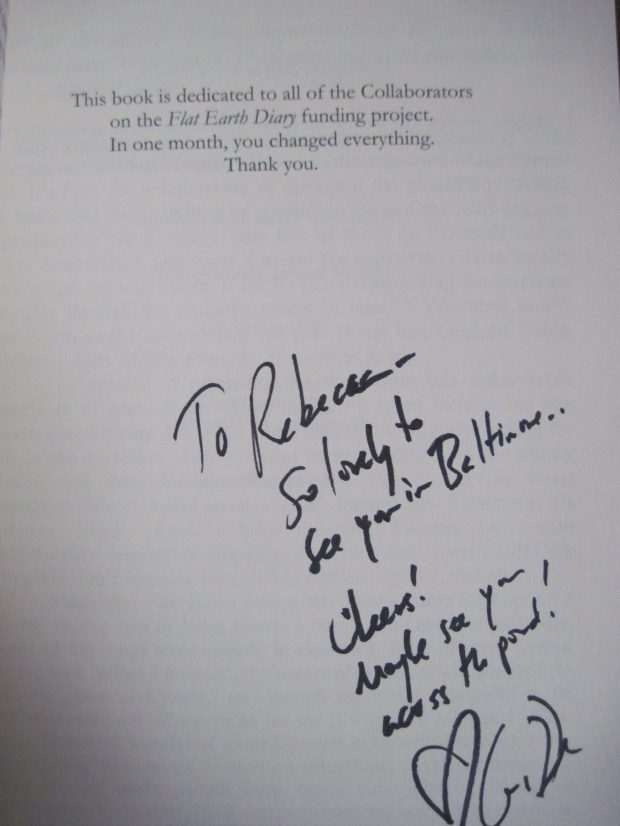

Krista Detor is one of our favorite singer-songwriters. We’ll be seeing her play for the fourth time in March. Luckily for us (but unluckily for the world, and for her coffers), this folk songstress from Indiana is unknown enough to play folk clubs and house concerts on both sides of the Atlantic. She wrote a book documenting the creative process behind her next-to-last album; when I saw her in Maryland she signed it with “Maybe see you across the pond!”

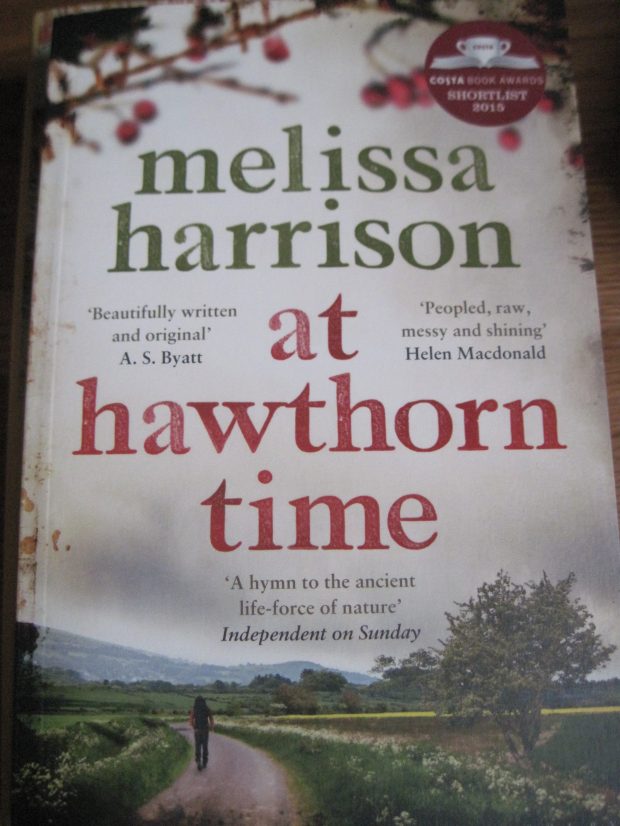

I have yet to read one of Melissa Harrison’s books, though I’m interested in her novels and her book on British weather. However, she edited the Seasons anthologies issued by the Wildlife Trusts last year – two of which my husband’s writing appeared in. When she spoke on the University of Reading campus about notions of the countryside in literature, my husband went along to meet her and bought a paperback of her second novel for her to sign.

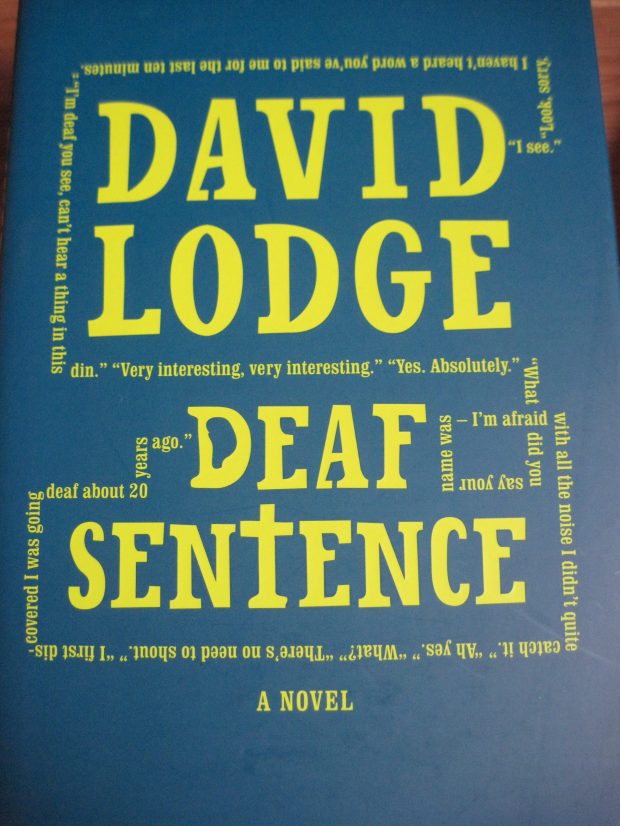

I’ve seen David Lodge speak twice, both times at the London Review Bookshop. He’s one of my favorite authors ever but, alas, isn’t all that funny or personable live; his autobiography is similarly humorless compared to his novels. Deaf Sentence was a return to his usual comic style after his first stab at historical fiction (Author, Author, about Henry James’s later life). The second time I saw him he was promoting A Man of Parts, which again imagines the inner life of a famous author – this time H.G. Wells.

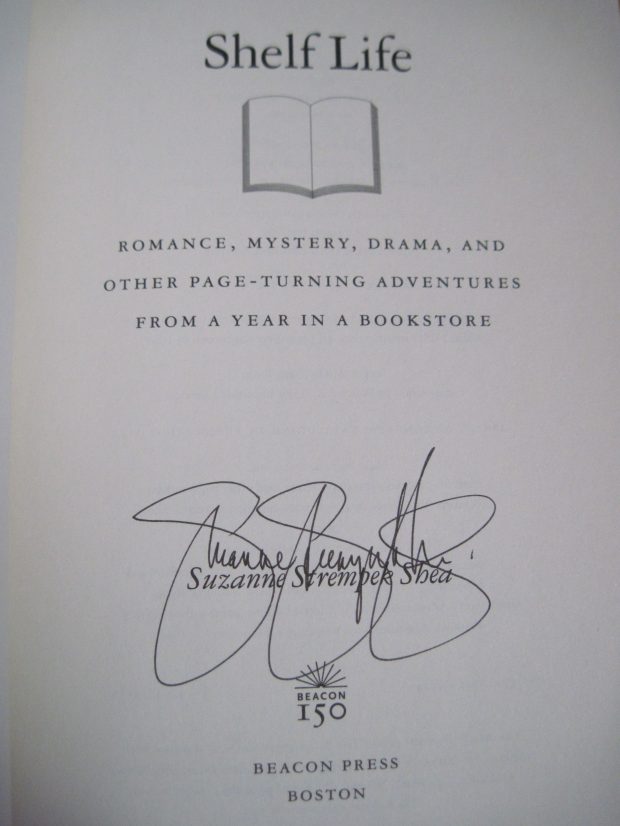

An obscene bargain from Amazon that just happened to be signed. I’m looking forward to starting this one soon: books about book are (almost) always such a cozy delight.

- You can tell she enjoys her S’s.

Plus three signed copies languishing in boxes in America:

- Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott: I love Lamott’s nonfiction but have never tried one of her novels. I found this one at a library book sale, going for $1; I guess nobody noticed the signature.

- The Sixteenth of June by Maya Lang: I originally read the book via NetGalley, but it quickly became a favorite. After she saw my five-star review, Maya asked me to help her out with word-of-mouth promotion and was kind enough to send me a signed copy as thanks.

- The Life of D.H. Lawrence: An Illustrated Biography by Keith M. Sagar: Sagar was one of the keynote speakers at the D.H. Lawrence Society of North America conference I attended in the summer of 2005.

Barcode by Jordan Frith: The barcode was patented in 1952 but didn’t come into daily use until 1974. It was developed for use by supermarkets – the Universal Product Code or UPC. (These days a charity shop is the only place you might have a shopping experience that doesn’t rely on barcodes.) A grocery industry committee chose between seven designs, two of which were round. IBM’s design won and became the barcode as we know it. “Barcodes are a bit of a paradox,” Frith, a communications professor with previous books on RFID and smartphones to his name, writes. “They are ignored yet iconic. They are a prime example of the learned invisibility of infrastructure yet also a prominent symbol of cultural critique in everything from popular science fiction to tattoos.” In 1992, President Bush was considered to be out of touch when he expressed amazement at barcode scanning technology. I was most engaged with the chapter on the Bible – Evangelicals, famously, panicked that the Mark of the Beast heralded by the book of Revelation would be an obligatory barcode tattooed on every individual. While I’m not interested enough in technology to have read the whole thing, which does skew dry, I found interesting tidbits by skimming. (Public library) [152 pages]

Barcode by Jordan Frith: The barcode was patented in 1952 but didn’t come into daily use until 1974. It was developed for use by supermarkets – the Universal Product Code or UPC. (These days a charity shop is the only place you might have a shopping experience that doesn’t rely on barcodes.) A grocery industry committee chose between seven designs, two of which were round. IBM’s design won and became the barcode as we know it. “Barcodes are a bit of a paradox,” Frith, a communications professor with previous books on RFID and smartphones to his name, writes. “They are ignored yet iconic. They are a prime example of the learned invisibility of infrastructure yet also a prominent symbol of cultural critique in everything from popular science fiction to tattoos.” In 1992, President Bush was considered to be out of touch when he expressed amazement at barcode scanning technology. I was most engaged with the chapter on the Bible – Evangelicals, famously, panicked that the Mark of the Beast heralded by the book of Revelation would be an obligatory barcode tattooed on every individual. While I’m not interested enough in technology to have read the whole thing, which does skew dry, I found interesting tidbits by skimming. (Public library) [152 pages]  Island by Julian Hanna: The most autobiographical, loosest and least formulaic of these three, and perhaps my favourite in the series to date. Hanna grew up on Vancouver Island and has lived on Madeira; his genealogy stretches back to another island nation, Ireland. Through disparate travels he comments on islands that have long attracted expats: Hawaii, Ibiza, and Hong Kong. From sweltering Crete to the polar night, from family legend to Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, the topics are as various as the settings. Although Hanna is a humanities lecturer, he even gets involved in designing a gravity battery for Eday in the Orkneys (fully powered by renewables), having won funding through a sustainable energy prize, and is part of a team that builds one in situ there in three days. I admired the honest exploration of the positives and negatives of islands. An island can promise paradise, a time out of time, “a refuge for eccentrics.” Equally, it can be a site of isolation, of “domination and exploitation of fellow humans and of nature.” We may think that with the Internet the world has gotten smaller, but islands are still bastions of distinct culture. In an era of climate crisis, though, some will literally cease to exist. Written primarily during the Covid years, the book contrasts the often personal realities of death, grief and loneliness with idyllic desert-island visions. Whimsically, Hanna presents each chapter as a message in a bottle. What a different book this would have been if written by, say, a geographer. (Read via Edelweiss) [180 pages]

Island by Julian Hanna: The most autobiographical, loosest and least formulaic of these three, and perhaps my favourite in the series to date. Hanna grew up on Vancouver Island and has lived on Madeira; his genealogy stretches back to another island nation, Ireland. Through disparate travels he comments on islands that have long attracted expats: Hawaii, Ibiza, and Hong Kong. From sweltering Crete to the polar night, from family legend to Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, the topics are as various as the settings. Although Hanna is a humanities lecturer, he even gets involved in designing a gravity battery for Eday in the Orkneys (fully powered by renewables), having won funding through a sustainable energy prize, and is part of a team that builds one in situ there in three days. I admired the honest exploration of the positives and negatives of islands. An island can promise paradise, a time out of time, “a refuge for eccentrics.” Equally, it can be a site of isolation, of “domination and exploitation of fellow humans and of nature.” We may think that with the Internet the world has gotten smaller, but islands are still bastions of distinct culture. In an era of climate crisis, though, some will literally cease to exist. Written primarily during the Covid years, the book contrasts the often personal realities of death, grief and loneliness with idyllic desert-island visions. Whimsically, Hanna presents each chapter as a message in a bottle. What a different book this would have been if written by, say, a geographer. (Read via Edelweiss) [180 pages]  X-Ray by Nicole Lobdell: X-ray technology has been with us since 1895, when it was developed by German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen. He received the first Nobel Prize in physics but never made any money off of his discovery and died in penury of a cancer that likely resulted from his work. From the start, X-rays provoked concerns about voyeurism. People were right to be wary of X-rays in those early days, but radiation was more of a danger than the invasion of privacy. Lobdell, an English professor, tends to draw slightly simplistic metaphorical messages about the secrets of the body. But X-rays make so many fascinating cultural appearances that I could forgive the occasional lack of subtlety. There’s an in-depth discussion of H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man, and Superman was only one of the comic-book heroes to boast X-ray vision. The technology has been used to measure feet for shoes, reveal the hidden history of paintings, and keep air travellers safe. I went in for a hospital X-ray of my foot not long after reading this. It was such a quick and simple process, as you’ll find at the dentist’s office as well, and safe enough that my radiographer was pregnant. (Read via Edelweiss) [152 pages]

X-Ray by Nicole Lobdell: X-ray technology has been with us since 1895, when it was developed by German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen. He received the first Nobel Prize in physics but never made any money off of his discovery and died in penury of a cancer that likely resulted from his work. From the start, X-rays provoked concerns about voyeurism. People were right to be wary of X-rays in those early days, but radiation was more of a danger than the invasion of privacy. Lobdell, an English professor, tends to draw slightly simplistic metaphorical messages about the secrets of the body. But X-rays make so many fascinating cultural appearances that I could forgive the occasional lack of subtlety. There’s an in-depth discussion of H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man, and Superman was only one of the comic-book heroes to boast X-ray vision. The technology has been used to measure feet for shoes, reveal the hidden history of paintings, and keep air travellers safe. I went in for a hospital X-ray of my foot not long after reading this. It was such a quick and simple process, as you’ll find at the dentist’s office as well, and safe enough that my radiographer was pregnant. (Read via Edelweiss) [152 pages]

The Portable Veblen by Elizabeth McKenzie: Veblen, named after the late-nineteenth-century Norwegian-American economist, is one of the oddest heroines you’ll ever meet. She thinks squirrels are talking to her and kisses flowers. But McKenzie doesn’t just play Veblen for laughs; she makes her a believable character well aware of her own psychological backstory. I suspect the squirrel material could be a potential turn-off for readers who can’t handle too much whimsy. Over-the-top silly in places, this is nonetheless a serious account of the difficulty of Veblen and Paul, her neurology researcher fiancé, blending their dysfunctional families and different ideologies – which is what marriage is all about.

The Portable Veblen by Elizabeth McKenzie: Veblen, named after the late-nineteenth-century Norwegian-American economist, is one of the oddest heroines you’ll ever meet. She thinks squirrels are talking to her and kisses flowers. But McKenzie doesn’t just play Veblen for laughs; she makes her a believable character well aware of her own psychological backstory. I suspect the squirrel material could be a potential turn-off for readers who can’t handle too much whimsy. Over-the-top silly in places, this is nonetheless a serious account of the difficulty of Veblen and Paul, her neurology researcher fiancé, blending their dysfunctional families and different ideologies – which is what marriage is all about. Weathering by Lucy Wood: This atmospheric debut novel is set in a crumbling house by an English river and stars three generations of women – one of them a ghost. Ada has returned to her childhood home after 13 years to scatter her mother Pearl’s ashes, sort through her belongings, and get the property ready to sell. In a sense, then, this is a haunted house story. Yet Wood introduces the traces of magical realism so subtly that they never feel jolting. Like the river, the novel is fluid, moving between the past and present with ease. The vivid picture of the English countryside and clear-eyed look at family dynamics remind me most of Tessa Hadley (

Weathering by Lucy Wood: This atmospheric debut novel is set in a crumbling house by an English river and stars three generations of women – one of them a ghost. Ada has returned to her childhood home after 13 years to scatter her mother Pearl’s ashes, sort through her belongings, and get the property ready to sell. In a sense, then, this is a haunted house story. Yet Wood introduces the traces of magical realism so subtly that they never feel jolting. Like the river, the novel is fluid, moving between the past and present with ease. The vivid picture of the English countryside and clear-eyed look at family dynamics remind me most of Tessa Hadley (

The Life and Death of Sophie Stark by Anna North: The twisty, clever story of a doomed filmmaker – perfect for fans of

The Life and Death of Sophie Stark by Anna North: The twisty, clever story of a doomed filmmaker – perfect for fans of  Casualties by Betsy Marro: A powerful, melancholy debut novel about how war affects whole families, not just individual soldiers. As in Bill Clegg’s

Casualties by Betsy Marro: A powerful, melancholy debut novel about how war affects whole families, not just individual soldiers. As in Bill Clegg’s  Mr. Splitfoot

Mr. Splitfoot Rush Oh! by Shirley Barrett: A debut novel in which an Australian whaler’s daughter looks back at 1908, a catastrophic whaling season but also her first chance at romance. I felt that additional narrators, such as a whaleman or an omniscient voice, would have allowed for more climactic scenes. Still, I found this gently funny, especially the fact that the family’s cow and horse are inseparable and must be together on any outing. There are some great descriptions of whales, too.

Rush Oh! by Shirley Barrett: A debut novel in which an Australian whaler’s daughter looks back at 1908, a catastrophic whaling season but also her first chance at romance. I felt that additional narrators, such as a whaleman or an omniscient voice, would have allowed for more climactic scenes. Still, I found this gently funny, especially the fact that the family’s cow and horse are inseparable and must be together on any outing. There are some great descriptions of whales, too. Felicity by Mary Oliver: I was disappointed with my first taste of Mary Oliver’s poetry. So many readers praise her work to the skies, and I’ve loved excerpts I’ve read elsewhere. However, I found these to be rather simplistic and clichéd, especially poems’ final lines, e.g. “Soon now, I’ll turn and start for home. / And who knows, maybe I’ll be singing.” or “Late, late, but now lovely and lovelier. / And the two of us, together—a part of it.” I’ll definitely try more of her work, but I’ll look out for an older, classic collection.

Felicity by Mary Oliver: I was disappointed with my first taste of Mary Oliver’s poetry. So many readers praise her work to the skies, and I’ve loved excerpts I’ve read elsewhere. However, I found these to be rather simplistic and clichéd, especially poems’ final lines, e.g. “Soon now, I’ll turn and start for home. / And who knows, maybe I’ll be singing.” or “Late, late, but now lovely and lovelier. / And the two of us, together—a part of it.” I’ll definitely try more of her work, but I’ll look out for an older, classic collection. Paulina & Fran by Rachel B. Glaser: Full of blunt, faux-profound sentences and smutty, two-dimensional characters. Others may rave about it, but this wasn’t for me. I get that it is a satire on female friendship and youth entitlement. But I hated how the main characters get involved in a love triangle, and once they leave college any interest I had in them largely disappeared. Least favorite lines: “Paulina. She’s like Cleopatra, but more squat.” / “She’s more like Humphrey Bogart” and “She craved the zen-ness of being rammed.”

Paulina & Fran by Rachel B. Glaser: Full of blunt, faux-profound sentences and smutty, two-dimensional characters. Others may rave about it, but this wasn’t for me. I get that it is a satire on female friendship and youth entitlement. But I hated how the main characters get involved in a love triangle, and once they leave college any interest I had in them largely disappeared. Least favorite lines: “Paulina. She’s like Cleopatra, but more squat.” / “She’s more like Humphrey Bogart” and “She craved the zen-ness of being rammed.”

Noah’s Wife by Lindsay Starck: I kept wanting to love this book, but never quite did. It’s more interesting as a set of ideas – a town where it won’t stop raining, a minister losing faith, homeless zoo animals sheltering with ordinary folk – than as an executed plot. My main problem was that the minor characters take over so that you never get to know the title character, who remains nameless. There’s also a ton of platitudes towards the end. It reminded me most of

Noah’s Wife by Lindsay Starck: I kept wanting to love this book, but never quite did. It’s more interesting as a set of ideas – a town where it won’t stop raining, a minister losing faith, homeless zoo animals sheltering with ordinary folk – than as an executed plot. My main problem was that the minor characters take over so that you never get to know the title character, who remains nameless. There’s also a ton of platitudes towards the end. It reminded me most of  Spill Simmer Falter Wither by Sara Baume: This sounded like a charmingly offbeat story about a loner and his adopted dog setting off on a journey. As it turns out, this debut is much darker than expected, but what saves it from being unremittingly depressing is the same careful attention to voice you encounter in fellow Irish writers like Donal Ryan and Anne Enright. It’s organized into four sections, with the title’s four verbs as headings. In a novel low on action, the road trip is much the most repetitive section, extending to the language as well. Even so, Baume succeeds in giving a compassionate picture of a character whose mental state comes into question. (Full review in March 2016 issue of Third Way magazine.)

Spill Simmer Falter Wither by Sara Baume: This sounded like a charmingly offbeat story about a loner and his adopted dog setting off on a journey. As it turns out, this debut is much darker than expected, but what saves it from being unremittingly depressing is the same careful attention to voice you encounter in fellow Irish writers like Donal Ryan and Anne Enright. It’s organized into four sections, with the title’s four verbs as headings. In a novel low on action, the road trip is much the most repetitive section, extending to the language as well. Even so, Baume succeeds in giving a compassionate picture of a character whose mental state comes into question. (Full review in March 2016 issue of Third Way magazine.) Medium Hero

Medium Hero Glitter and Glue

Glitter and Glue The Ballroom

The Ballroom Life without a Recipe

Life without a Recipe Arctic Summer

Arctic Summer