My 10 Favorite Books from the Past Decade

I make no claims to objectivity here. These are simply 10 books that stand out to me from the past decade. I narrowed the list down from about 25 titles, trying not to agonize over it for too long. I’m pleased that it happens to be half female, with two POC and one work in translation. (Could be more diverse, but not too bad.)

You can see the seeds of my interest in memoirs and medical books, and the variety of fiction I love, from absurdist comedy (Auslander) to Greek-level tragedy (Vann).

In alphabetical order by author surname:

Hope: A Tragedy by Shalom Auslander (2012)

Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler (2016)

We, the Drowned by Carsten Jensen (English translation, 2010)

Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood (2017)

H Is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald (2014)

Want Not by Jonathan Miles (2013)

The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer by Siddhartha Mukherjee (2010)

A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki (2013)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot (2010)

Caribou Island by David Vann (2010)

These selections skew early in the decade; 2010‒13 happened to be particularly memorable reading years for me. All of these are books I would like to reread, sooner rather than later.

(Five of these are repeated from the list of favorite books I drew up for my 35th birthday.)

Do we overlap on any favorites?

Which books of the 2010s were standouts for you?

Thoughts on the Wellcome Book Prize Longlist

The 2018 Wellcome Book Prize longlist is here! From the prize’s website, you can click on any of these 12 books’ covers, titles or authors to get more information about them.

Some initial thoughts:

I correctly predicted three of the entries (or 25%) in yesterday’s post: In Pursuit of Memory by Joseph Jebelli, With the End in Mind by Kathryn Mannix, and I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell. I’m pretty shocked to not see Fragile Lives or Admissions on the list.

Of the remainder, I’ve already read one (Midwinter Break) and DNFed another (Stay with Me). Midwinter Break didn’t immediately suggest itself to me for this prize because its themes of ageing and alcoholism are the background to a story about the disintegration of a long marriage. Nonetheless, it’s a lovely book that hasn’t gotten as much attention as it deserves – it was on my runners-up list from last year – so I’m delighted to see it nominated. Stay with Me was also on the Women’s Prize shortlist; it appears here for its infertility theme, but I wouldn’t attempt it again unless it made the Wellcome shortlist.

As to the rest:

- I’m annoyed with myself for not remembering The Butchering Art, which I have on my Kindle. Sometimes I assume that books I’ve gotten from NetGalley are USA-only and don’t check for a UK publisher. I plan to read this and With the End in Mind (also on my Kindle) soon.

- I already knew about and was interested in Mayhem and The White Book.

- Of the ones I didn’t know about, Plot 29 appeals to me the most. I’m off to get it from the library this very afternoon, in fact. Its health theme seems quite subtle: it’s about a devoted gardener ‘digging’ into his past in an abusive family and foster care. The Guardian review describes it thus: “Like Helen Macdonald’s H Is for Hawk, this is a profoundly moving account of mental trauma told through the author’s encounters with nature. Jenkins sees his garden as a place where a person can try to escape from, and atone for, the darkness of human existence.” This is the great thing about prize lists: they can introduce you to fascinating books you might never have heard of otherwise. Even if it’s just one book that takes your fancy, who knows? It might end up being a favorite.

- While I’m not immediately drawn to the books on the history of vaccines, the evolution of human behavior, and transhumanism, I will certainly be glad to read them if they make the shortlist.

Some statistics on this year’s longlist, courtesy of the press release I was sent by e-mail:

- Three novels, three memoirs, and six nonfiction titles

- Five debut authors

- Three titles from independent publishers (Canongate and Granta/Portobello Books)

- The authors are from the UK, Ireland, USA, Nigeria, Canada, and – making their first appearance – Sweden (Sigrid Rausing) and South Korea (Han Kang)

Chair of judges Edmund de Waal writes: “The Wellcome Book Prize is unique in its reach across genres, and so the range of books that we have considered has been exhilarating in its extent and ambition. This is a remarkable time for readers, with a great flourishing of writing on ideas around science, medicine and health, lives and deaths, histories and futures. After passionate discussions we have arrived at our longlist for the Wellcome Book Prize 2018 and are proud to be part of this process of bringing to a wider public these 12 tremendous books that have moved, intrigued and inspired us. All of them bring something new to our understanding of what it is to be human.”

The shortlist is announced on Tuesday, March 20th, and the winner will be revealed on Monday, April 30th.

Are there any books on here that you’d like to read?

A Wood of One’s Own by Ruth Pavey

In 1999 Ruth Pavey bought four acres of Somerset scrubland at a land auction. It wasn’t exactly what she’d set out to acquire: it wasn’t a “pretty” field, and traffic was audible from it. But she was pleased to return to her family’s roots in the Somerset Levels area – this “silted place of slow waters, eels, reeds, drainage engineers, buttercups, church towers, quiet” that her father came from, and where she was born – and she fancied planting some trees.

There never was a master plan […] I wanted to open up enough room for trees that might live for centuries […] I also wanted to keep areas of wilderness for the creatures […] And I wanted it to be beautiful. Not immaculate, that was too much to hope for, but, in its own ragged, benign way, beautiful.

This pleasantly meandering memoir, Pavey’s first book, is an account of nearly two decades spent working alongside nature to restore some of her land to orchard and maintain the rest in good health. The first steps were clear: she had to deal with some fallen willows, find a water source and plan a temporary shelter. Rather than a shed, which would be taken as evidence of permanent residency, she resorted to a “Rollalong,” a mobile metal cabin she could heat just enough to survive nights spent on site. Before long, though, she bought a nearby cottage to serve as her base when she left her London teaching job behind on weekends.

This pleasantly meandering memoir, Pavey’s first book, is an account of nearly two decades spent working alongside nature to restore some of her land to orchard and maintain the rest in good health. The first steps were clear: she had to deal with some fallen willows, find a water source and plan a temporary shelter. Rather than a shed, which would be taken as evidence of permanent residency, she resorted to a “Rollalong,” a mobile metal cabin she could heat just enough to survive nights spent on site. Before long, though, she bought a nearby cottage to serve as her base when she left her London teaching job behind on weekends.

Then came the hard work: after buying trees from nurseries and ordering apple varieties that would fruit quickly, Pavey had to plant it all and pick up enough knowledge about pruning, grafting, squirrel management, canker and so on to keep everything alive. There was always something new to learn, and plenty of surprises – such as the stray llama that visited her neighbor’s orchard. Local history weaves through this story, too: everything from the English Civil War to Cecil Sharp’s collecting of folk songs.

Britain has seen a recent flourishing of hybrid memoirs–nature books by the likes of Helen Macdonald, Mallachy Tallack and Clover Stroud. By comparison, Pavey is not as confiding about her personal life as you might expect. She reveals precious little about herself: she tells us that her mother died when she was young and she was mostly raised by an aunt; she hints at some failed love affairs; in the acknowledgments she mentions a son; from the jacket copy I know she’s the gardening correspondent for the Hampstead & Highgate Express. But that’s it. This really is all about the wood, and apart from serving as an apt Woolf reference the use of “one” in the title is in deliberate opposition to the confessional connotations of “my”.

Still, I think this book will appeal to readers of modern nature writers like Paul Evans and Mark Cocker – these two are Guardian Country Diarists, and Pavey develops the same healthy habit of sticking to one patch and lovingly monitoring its every development. I was also reminded of Peri McQuay’s memoir of building a home in the woods of Canada.

Still, I think this book will appeal to readers of modern nature writers like Paul Evans and Mark Cocker – these two are Guardian Country Diarists, and Pavey develops the same healthy habit of sticking to one patch and lovingly monitoring its every development. I was also reminded of Peri McQuay’s memoir of building a home in the woods of Canada.

What struck me most was how this undertaking encourages the long view: “being finished, in the sense of being brought to a satisfactory conclusion, is not something that happens in a garden, an orchard or a wood, however well planned or cultivated,” she writes. It’s an ongoing project, and she avoids nostalgia and melodrama in planning for its future after she’s gone; “I am only there for a while, a twinkling. But [the trees and creatures] … will remain.” This would make a good Christmas present for the dedicated gardener in your life, not least because of the inclusion of Pavey’s lovely black-and-white line drawings.

A Wood of One’s Own was published on September 21st by Duckworth Overlook. My thanks to the publisher for a free copy for review.

My rating:

Autumn Is Here, in Poetry and Prose

“The trees are undressing, and fling in many places –

On the gray road, the roof, the window-sill –

Their radiant robes and ribbons and yellow laces”

~from “Last Week in October,” Thomas Hardy (1928)

I recently learned that there are two different official start dates for autumn. The meteorological beginning of the season was on September 1st, while the astronomical opening is not until the 22nd. For the purposes of this review I’ll incline towards the former. I’ve been watching leaves fall since early last month, after all, but now – after a weekend spent taking a chilly boat ride down the canal, stocking the freezer with blackberries and elderberries, and setting hops to dry in the shed – it truly feels like autumn is here in southern England. Luckily, I had just the right book in hand to read over the last couple of weeks as I’ve been settling into our new place, Autumn: An anthology for the changing seasons.

This is the third of four seasonal volumes issued this year by the UK’s Wildlife Trusts, in partnership with London-based publisher Elliott & Thompson and edited by Melissa Harrison (see also my review of Summer). The format of all the books is roughly the same: pieces range from one to a few pages and run the gamut from recurring phenological records (Gilbert White and Thomas Furly Forster) and extracts from classic literature (poems by Shelley, Tennyson and Yeats) to recent nature writers (an excerpt from Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk; new work from Amy Liptrot and John Lewis-Stempel). Perhaps half the content has been contributed by talented amateurs, about 10 of them repeats from the first volumes.

This is the third of four seasonal volumes issued this year by the UK’s Wildlife Trusts, in partnership with London-based publisher Elliott & Thompson and edited by Melissa Harrison (see also my review of Summer). The format of all the books is roughly the same: pieces range from one to a few pages and run the gamut from recurring phenological records (Gilbert White and Thomas Furly Forster) and extracts from classic literature (poems by Shelley, Tennyson and Yeats) to recent nature writers (an excerpt from Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk; new work from Amy Liptrot and John Lewis-Stempel). Perhaps half the content has been contributed by talented amateurs, about 10 of them repeats from the first volumes.

This collection was slightly less memorable for me than Summer. A few pieces seem like school assignments, overly reliant on clichés of blackberry picking and crunching leaves underfoot. The best ones don’t attempt too much; they zero in on one species or experience and give a complete, self-contained story rather than general musings. A few stand-outs in this respect are Jo Cartnell chancing upon bank voles, Julian Jones on his obsession with eels, Laurence Arnold telling of his reptile surveying at London Wetland Center, and Lucy McRobert having a magic moment with dolphins off the Scilly Isles. I also enjoyed Kate Blincoe’s account of foraging for giant puffball mushrooms and Janet Willoner on pressing apples into juice – I’m looking forward to watching this at our town’s Apple Day in October.

I think all the contemporary writers would agree that you don’t have to live or go somewhere ‘special’ to commune with nature; there are marvels everywhere, even on your own tiny patch, if you will just go out and find them. For instance, South London seems an unlikely place for wildlife encounters, yet Will Harper-Penrose meets up with one of the country’s most strikingly exotic species (an introduced one), the ring-necked parakeet. Jane Adams comes across a persistent gang of wood mice in her very own attic, while Daphne Pleace spots red deer stags from the safety of her motorhome when on vacation in northwest Scotland.

A Japanese maple near the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Photo by Chris Foster.

Remarkably, the book’s disparate pieces together manage to convey a loose chronological progression, from the final days of lingering summer to the gradual onset of winter. Here’s Annie Worsley’s lovely portrayal of autumn’s approach: “In the woodlands the first trees to betray summer are silver birches: splashes of yellow dapple their fine, shimmering greenery. Here and there, long wavering larch tresses begin to change from deep green to orange and ochre.” At the other end of the autumnal continuum, David Gwilym Anthony’s somber climate change poem, “Warming,” provides a perfect close to the anthology: “These days I’ll take what Nature sends / to hoard for dour December: / a glow of warmth as autumn ends.”

A few more favorite lines:

- “Dusk, when the edges of all things blur. A time of mauve and moonlight, of shapeshiftings and stirrings, of magic.” (Alexi Francis)

- “Go down the village street on a late September afternoon and the warm burnt smell of jam-making oozes out of open cottage doors.” (Clare Leighton, 1933)

- “There are miniature Serengetis like this under most logs, if you take the time to look.” (Ryan Clark)

- “Ah, the full autumn Bisto bouquet comes powering to the nose: mouldering leaves, decaying mushrooms, rusting earth.” (John Lewis-Stempel)

My favorite essay of all, though, is by Jon Dunn: playful yet ultimately elegiac, it’s about returning to his croft on a remote Shetland island to find that an otter has been picking off his chickens.

All Saint’s Church in Woolstone, Oxfordshire. Photo by Chris Foster.

Like Summer, this gives a good sense of autumn as a whole, including its metaphorical associations. As Harrison puts it in her introduction, autumn “makes tangible a suite of emotions – wistfulness, nostalgia, a comfortable kind of melancholy – that are, at other times of the year, just out of reach.” It’s been my favorite season since childhood, probably because it combines the start of the school year, my birthday, and American holidays like Halloween and Thanksgiving. Whatever your own experience of autumn – whether it’s a much loved season or not; even if you call it “fall” instead – I can highly recommend this anthology’s chorus of voices old and new. There’s no better way for a book lover to usher in the season.

With thanks to Jennie Condell at Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

My rating:

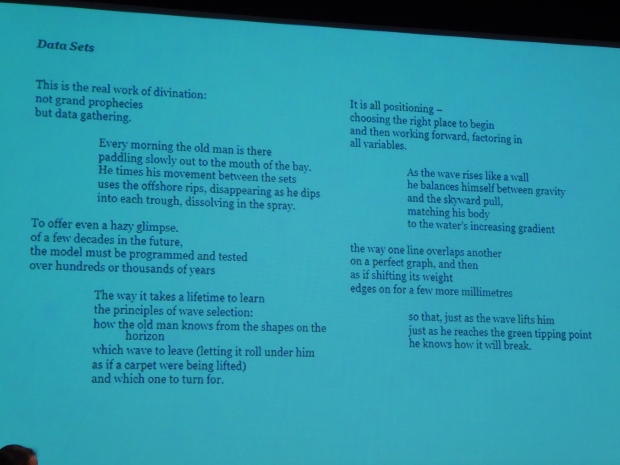

What Is Nature (Poetry) For?

I’ve been pondering this question thanks to an excellent conference my husband and I attended in Stamford in the middle of November: New Networks for Nature. This is the third year my husband (a teaching associate in the biology department at the University of Reading) has participated, and the second year in a row I’ve chosen one day to go. Last year I had the privilege of seeing some truly phenomenal nature writers. Dave Goulson spoke about his efforts to protect bumblebees; Helen Macdonald gave a reading from H is for Hawk; and Paul Evans and Mark Cocker were on a panel about being Guardian country diarists.

This year one of the conference highlights was a debate between Guardian journalist and rewilding proponent George Monbiot (Feral) and Tony Juniper (What Has Nature Ever Done for Us?), former head of Friends of the Earth. The topic: Is nature an economic resource or a thing of intrinsic value? Both gentlemen came out swinging and were at their most convincing.

Unless we make an economic case for preserving nature (pollinators, hydroelectric power, ecotourism), Juniper believes, we will lose it. If we reframe our approach to play on bastard politicians’ turf, Monbiot counters, we’ve already lost our integrity. Nature is worth saving for its own sake; the problem is not our arguments but our lack of power.

I tended to agree with Juniper: we aren’t winning the conservation debate in any other way, so why not introduce financial incentives? This doesn’t stop us from appreciating nature for aesthetic and spiritual reasons; it’s just another strategy.

I amused myself by imagining the opponents as a solitary noble knight waving the flag of idealism (Monbiot) and a new Noah packing nature into a money-papered Trojan horse to trick the pesky government (Juniper).

Male house sparrow. Courtesy of Chris Foster

If these two, in a roundabout way, pondered what nature is for, the previous session had asked more specifically what nature poetry is for. Led by Ruth Padel, one of my favorite poets, the roster also included Jo Shapcott and Pascale Petit. Each read from her work for 15 minutes and then together they answered audience questions as a panel.

I’d never heard of Petit but ended up loving her poems – they were the highlight of my day. One was about the piece of land her mother left her in France; she asked herself in what sense she could possess the place, and soon realized that it was really a pair of resident kingfishers who owned it. She writes around her difficult childhood, imagining a father who could never be cruel to birds – but then picturing him polishing off an ortolan bunting as his last meal, as Mitterrand was said to do. Along with birds, big cats provide many of the metaphors in her work, including Aramis, a black jaguar in the Paris Zoo, and the jaguar corridor in Belize.

Padel read “The Alligator’s Great Need and Great Desire,” followed by several poems from The Mara Crossing that she had written for members of the conference steering committee, such as one about storm petrels off the Skelligs and a snippet of biographical verse about Audubon. The lovely “Nocturne” commemorates nightly jellyfish migration, a “ghostly flotilla.”

She also read one that she said was the closest she gets to an angry poem: “The Forest, the Corrupt Official and a Bowl of Penis Soup” (from 2004’s The Soho Leopard), on the absurdity of killing rare animals – in this case the tiger – so their parts can be used in medicine or cuisine. Her final reading, from memory, was “Tiger Drinking at Forest Pool”; I nearly teared up when she spoke of “Sadness healed. Haven, in the mind, // To anyone hurt by littleness.”

Shapcott read two series of wildlife-themed poems. The first set, commissioned by Padel for the Zoological Society of London, was about the slender loris, which is also suffering from its use in traditional medicine as well as habitat loss. The second was a sequence about beekeeping, from the perspective of a woman who has just been left by a beekeeper. “Telling the Bees” reflects the folk belief that you have to inform bees of major events or they will leave; it ends “he’s gone, honeys; now you’re mine.” As the poem cycle continues, the hive becomes incorporated into her body until she can’t be separated from the bees.

Padel prefaced the discussion by asking how poetry should be in the face of extinctions and the destruction of the planet. She believes a sophistication of voice and expression is required; it’s not a matter of grabbing people by the lapels and saying “LOOK AT THIS,” but of putting the details together and being a witness.

Buff-tailed bumblebee. Courtesy of Chris Foster.

Shapcott echoed her with Heidegger’s query – what is the poet for in a desperate time? She reiterated that the poet should hold up key questions and let them resonate in people’s imaginations, not force-feed answers. Petit added that in her poetry birds are metaphors for the exploitation for the weak. All three agreed poetry is about embodiment, sensory response to the world – essential since we live least in our bodies of any species, Shapcott observed.

The theme of this year’s conference was “Place and Belonging,” and it struck me that all three poets were responding to the idea that nature belongs to us and can be used like any other possession. Instead, they reply, we should think about the places we belong to, and how we can serve rather than exploit nature. But the key is not to spell that out in polemic verse, but rather to speak of life’s particulars and hope that we manage to point to the universal.

I’ll end with part of a stanza from Padel’s “The Watcher” that seems to reinforce the personal, spiritual value of nature that so much of the conference suggested:

Quest for the sacred. And if I

could track that one stork down

on its winter ground, maybe I’d know

what has become of life and me

and where to go. I’d pour libations, follow

the omen, set up sacrifice

to the god of wayfarers, even pay a call

on the seer who decodes

the flight of birds. I’d prophesy.

What Makes a Review Popular?

I’ve only been reviewing on Goodreads for a couple years, but in that time I’ve noticed some contradictory trends. The most-liked reviews can be thousands of words long or two sentences; disjointed ramblings or concise analysis; gif after gif (screen captures of moving or still images from TV or film) or pure text; strewn with typos or perfectly honed; personal or detached; gimmicky or straightforward; gushing praise or forthright dismissal. In other words, I’m somewhat puzzled as to what makes a review popular.

To some extent it’s down to the popularity of a reviewer: the more friends and followers they have, the more likely people are to ‘like’ their review (if you’re not familiar with Goodreads, it has a ‘like’ button just like on Facebook, and reviews of a certain book then arrange themselves in order with the ones with the highest likes on the top). But this isn’t a sure thing. Although top reviewers probably account for a good percentage of the most popular reviews, there are always those sneaky book reviews that come out of nowhere and go viral.

Here are my thoughts on what is likely to make a review popular, thinking not just of Goodreads but of other sites I’ve worked with:

The book has buzz already, and/or has won a major prize.

By far, my most popular review ever is of Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries [458 likes]. It won the Man Booker Prize in 2013.

My second most popular review ever is of Gabrielle Zevin’s The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry [264 likes]. It was a New York Times bestseller and especially successful with the bookish types on Goodreads.

My second most popular review ever is of Gabrielle Zevin’s The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry [264 likes]. It was a New York Times bestseller and especially successful with the bookish types on Goodreads.

To my knowledge, our most popular article ever published on Bookkaholic was a book debate we did about Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2013. I rated it 3 stars, while my opponent, an Australian blogger, gave it 5.

There’s thousands of 5-star ratings for Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, the 2015 Pulitzer winner, so while mine is not one of the top reviews by any means, it’s still my fifth most popular one at 62 likes.

You get in there early.

Mine was one of the first reviews of The Luminaries to hit Goodreads, thanks to an advanced reader’s copy sent to me by We Love This Book. I also managed to review A.J. Fikry a few weeks before the publication date thanks to an Edelweiss download. With an early review, you can sometimes set the trend.

Mine was one of the first reviews of The Luminaries to hit Goodreads, thanks to an advanced reader’s copy sent to me by We Love This Book. I also managed to review A.J. Fikry a few weeks before the publication date thanks to an Edelweiss download. With an early review, you can sometimes set the trend.

Helen Macdonald’s superb memoir, H is for Hawk, was released in the UK about a year before it finally arrived in the States, so that allowed my review time to gain some momentum (though not as much as a review that contained lots of photographs, something I still haven’t figured out how to do in html). It’s my sixth most popular review at 48 likes.

You epitomize the positive (or dissenting) response.

My third most popular review is of Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being [138 likes], one of my favorite books from 2013 or any year. That was an unreserved 5-star rating. My 5-star review of Jo Baker’s Longbourn, my fourth most popular at 64 likes, went up the week of publication and started off strong before being overtaken by some other positive reviews.

My third most popular review is of Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being [138 likes], one of my favorite books from 2013 or any year. That was an unreserved 5-star rating. My 5-star review of Jo Baker’s Longbourn, my fourth most popular at 64 likes, went up the week of publication and started off strong before being overtaken by some other positive reviews.

By contrast, my reviews of The Luminaries and A.J. Fikry are lukewarm and critical, respectively. For the latter, I seem to represent the negative response: people who were disappointed by how clichéd and sappy a promising bibliophile’s novel turned out to be.

[Note: The above numbers were correct as of October 12, 2015; I will now stop updating them as it was taking up too much of my time and memory! My Goodreads teaser for A Little Life has now overtaken H is for Hawk as my sixth most popular review.]

Do you have any theories as to what makes a review popular? If you’re a blogger and/or reviewer, what have been some of your most popular pieces?

All comments welcome!

The Tsar of Love and Techno

The Tsar of Love and Techno

Mad Feast

Mad Feast Charlotte Brontë: A Life

Charlotte Brontë: A Life

Addiction Is Addiction

Addiction Is Addiction The Gratitude Diaries by Janice Kaplan: We can all do with a little encouragement to appreciate what we already have. In so many areas of life – finances, career, relationship, even the weather – we’re all too often hoping for more or better than what we are currently experiencing. Here Kaplan undertakes a year-long experiment to see if gratitude can improve every aspect of her life. She draws her information from interviews with researchers and celebrities, quotes from philosophers, and anecdotes from her own and friends’ lives. It’s easy, pleasant reading I’d recommend to fans of Gretchen Rubin.

The Gratitude Diaries by Janice Kaplan: We can all do with a little encouragement to appreciate what we already have. In so many areas of life – finances, career, relationship, even the weather – we’re all too often hoping for more or better than what we are currently experiencing. Here Kaplan undertakes a year-long experiment to see if gratitude can improve every aspect of her life. She draws her information from interviews with researchers and celebrities, quotes from philosophers, and anecdotes from her own and friends’ lives. It’s easy, pleasant reading I’d recommend to fans of Gretchen Rubin. The Water Book by Alok Jha: An interdisciplinary look at water’s remarkable properties and necessity for life on earth. For the most part, Jha pitches his work at an appropriate level. However, if it’s been a while since you studied chemistry at school, you may struggle. Part IV, on the search for water in space, is too in-depth for popular science and tediously long. In December 2013 Jha was part of a month-long Antarctic expedition. He uses the trip as an effective framing device, but I would have liked more memoiristic passages. All in all, I was hoping for less hard science and more reflection on water’s importance to human culture.

The Water Book by Alok Jha: An interdisciplinary look at water’s remarkable properties and necessity for life on earth. For the most part, Jha pitches his work at an appropriate level. However, if it’s been a while since you studied chemistry at school, you may struggle. Part IV, on the search for water in space, is too in-depth for popular science and tediously long. In December 2013 Jha was part of a month-long Antarctic expedition. He uses the trip as an effective framing device, but I would have liked more memoiristic passages. All in all, I was hoping for less hard science and more reflection on water’s importance to human culture. Claxton: Field Notes from a Small Planet by Mark Cocker: Mark Cocker is the Guardian’s country diarist for Norfolk. The short pieces in this book are reprints of his columns, some expanded or revised. I would advise keeping this as a bedside or coffee table book from which you read no more than one or two entries a week, so that you always stay in chronological sync. You’ll appreciate the book most if you experience nature along with Cocker, rather than reading from front cover to back in a few sittings. The problem with the latter approach is that there is inevitable repetition of topics across years. All told, after spending a vicarious year in Claxton, you’ll agree: “How miraculous that we are all here, now, in this one small place.”

Claxton: Field Notes from a Small Planet by Mark Cocker: Mark Cocker is the Guardian’s country diarist for Norfolk. The short pieces in this book are reprints of his columns, some expanded or revised. I would advise keeping this as a bedside or coffee table book from which you read no more than one or two entries a week, so that you always stay in chronological sync. You’ll appreciate the book most if you experience nature along with Cocker, rather than reading from front cover to back in a few sittings. The problem with the latter approach is that there is inevitable repetition of topics across years. All told, after spending a vicarious year in Claxton, you’ll agree: “How miraculous that we are all here, now, in this one small place.” A Mile Down by David Vann: Vann, better known for fiction, tells the real-life story of his ill-fated journeys at sea. He hired a Turkish crew to build him a boat of his own, and before long shoddy workmanship, language difficulties, bureaucracy, and debts started to make it all seem like a very bad idea. Was he cursed? Would he follow his father into suicide? The day-to-day details of boat-building and sailing can be tedious, and there’s an angry tone that’s unpleasant; Vann seems to think everybody else was incompetent or a crook. However, he does an incredible job of narrating two climactic storms he sailed through.

A Mile Down by David Vann: Vann, better known for fiction, tells the real-life story of his ill-fated journeys at sea. He hired a Turkish crew to build him a boat of his own, and before long shoddy workmanship, language difficulties, bureaucracy, and debts started to make it all seem like a very bad idea. Was he cursed? Would he follow his father into suicide? The day-to-day details of boat-building and sailing can be tedious, and there’s an angry tone that’s unpleasant; Vann seems to think everybody else was incompetent or a crook. However, he does an incredible job of narrating two climactic storms he sailed through.

Running on the March Wind by Lenore Keeshig: Keeshig is a First Nations Canadian; these poems are full of images of Nanabush the Trickster, language from legal Indian acts, and sly subversion of stereotypes – cowboys and Indians, the only good Indian is a dead Indian (in “Making New”), the white man’s burden, and so on. In places I found these more repetitive and polemical than musical, though I did especially like the series of poems on trees.

Running on the March Wind by Lenore Keeshig: Keeshig is a First Nations Canadian; these poems are full of images of Nanabush the Trickster, language from legal Indian acts, and sly subversion of stereotypes – cowboys and Indians, the only good Indian is a dead Indian (in “Making New”), the white man’s burden, and so on. In places I found these more repetitive and polemical than musical, though I did especially like the series of poems on trees. Very British Problems Abroad

Very British Problems Abroad Purity

Purity A Brief History of Seven Killings

A Brief History of Seven Killings Kitchens of the Great Midwest

Kitchens of the Great Midwest The Japanese Lover

The Japanese Lover Accidental Saints: Finding God in All the Wrong People

Accidental Saints: Finding God in All the Wrong People The Road to Little Dribbling: Adventures of an American in Britain by Bill Bryson: Bryson’s funniest book for many years. It meant a lot to me since I am also an American expat in England. Two points of criticism, though: although he moves roughly from southeast to northwest in the country, the stops he makes are pretty arbitrary, and his subjects of mockery are often what you’d call easy targets. Do we really need Bryson’s lead to scorn litterbugs and reality television celebrities? Still, I released many an audible snort of laughter while reading.

The Road to Little Dribbling: Adventures of an American in Britain by Bill Bryson: Bryson’s funniest book for many years. It meant a lot to me since I am also an American expat in England. Two points of criticism, though: although he moves roughly from southeast to northwest in the country, the stops he makes are pretty arbitrary, and his subjects of mockery are often what you’d call easy targets. Do we really need Bryson’s lead to scorn litterbugs and reality television celebrities? Still, I released many an audible snort of laughter while reading. Shaler’s Fish

Shaler’s Fish

Landfalls

Landfalls Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill: Not as innovative or profound as I was expecting given the rapturous reviews from so many quarters. It’s an attempt to tell an old, old story in a new way: wife finds out her husband is cheating. Offill’s style is fragmentary and aphoristic. Some of the facts and sayings are interesting, but most just sit there on the page and don’t add to the story. What I did find worthwhile was tracing the several tense and pronoun changes: from first-person, past tense into present tense, then to third-person and back to first-person for the final page.

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill: Not as innovative or profound as I was expecting given the rapturous reviews from so many quarters. It’s an attempt to tell an old, old story in a new way: wife finds out her husband is cheating. Offill’s style is fragmentary and aphoristic. Some of the facts and sayings are interesting, but most just sit there on the page and don’t add to the story. What I did find worthwhile was tracing the several tense and pronoun changes: from first-person, past tense into present tense, then to third-person and back to first-person for the final page. As Far As I Know by Roger McGough: A bit silly for my tastes; lots of puns and other plays on words. In style they feel like children’s poems, but with vocabulary and themes more suited to adults. I did like “Indefinite Definitions,” especially BRUPT: “A brupt is a person, curt and impolite / Brusque and impatient / Who thinks he’s always right.” The whole series is like that: words with the indefinite article cut off and an explanation playing on the original word’s connotations. From the “And So to Bed” concluding cycle, I loved Camp bed: “A la Recherche du Temps Perdu / on the bedside table / Gardenia on the pillow / Silk pyjamas neatly folded.”

As Far As I Know by Roger McGough: A bit silly for my tastes; lots of puns and other plays on words. In style they feel like children’s poems, but with vocabulary and themes more suited to adults. I did like “Indefinite Definitions,” especially BRUPT: “A brupt is a person, curt and impolite / Brusque and impatient / Who thinks he’s always right.” The whole series is like that: words with the indefinite article cut off and an explanation playing on the original word’s connotations. From the “And So to Bed” concluding cycle, I loved Camp bed: “A la Recherche du Temps Perdu / on the bedside table / Gardenia on the pillow / Silk pyjamas neatly folded.” The Penguin Lessons: What I Learned from a Remarkable Bird

The Penguin Lessons: What I Learned from a Remarkable Bird