Last Love Your Library of 2025 & Another for #DoorstoppersInDecember

Thanks to Eleanor, Margaret and Skai for writing about their recent library reading! Marcie also joined in with a post about completing Toronto Public Library’s 2025 Reading Challenge with books by Indigenous authors.

I managed to fit in a few more 2025 releases before Christmas. My plan for January is to focus on reading from my own shelves (which includes McKitterick Prize submissions and perhaps also review copies to catch up on), so expect next month to be a lighter one.

My recent reading has featured many mentions of how much libraries mean, particularly to young women.

In her autobiographical poetry collection Visitations (coming out in April), Julia Alvarez writes of how her family’s world changed when they moved to New York City from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s. “Waiting for My Father to Pick Me Up at the Library” adopts the tropes of Alice in Wonderland: as her future expands, her father’s life shrinks.

In her autobiographical poetry collection Visitations (coming out in April), Julia Alvarez writes of how her family’s world changed when they moved to New York City from the Dominican Republic in the 1960s. “Waiting for My Father to Pick Me Up at the Library” adopts the tropes of Alice in Wonderland: as her future expands, her father’s life shrinks.

In The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson, the public library is a haven for Mercy, growing up in Bradford in the 1960s. She can hardly believe it’s free for everyone to use, even Black people. Greek mythology is her escape from an upbringing that involves domestic violence and molestation. “It’s peaceful and quiet in the Library. No one shouts or throws things or hits anyone. If anyone talks, the Librarian puts a finger to her mouth and tells them to shush.”

In The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson, the public library is a haven for Mercy, growing up in Bradford in the 1960s. She can hardly believe it’s free for everyone to use, even Black people. Greek mythology is her escape from an upbringing that involves domestic violence and molestation. “It’s peaceful and quiet in the Library. No one shouts or throws things or hits anyone. If anyone talks, the Librarian puts a finger to her mouth and tells them to shush.”

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer affirms the social benefits of libraries: “I love bookstores for many reasons but revere both the idea and the practice of public libraries. To me, they embody the civic-scale practice of a gift economy and the notion of common property. … We don’t each have to own everything. The books at the library belong to everyone, serving the public with free books”.

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer affirms the social benefits of libraries: “I love bookstores for many reasons but revere both the idea and the practice of public libraries. To me, they embody the civic-scale practice of a gift economy and the notion of common property. … We don’t each have to own everything. The books at the library belong to everyone, serving the public with free books”.

After Rebecca Knuth retired from an academic career in library and information science, she moved to London for a master’s degree in creative nonfiction and joined the London Library as well as the public library. But in her memoir London Sojourn (coming out in January), she recalls that she caught the library bug early: “Each weekday, I bused to school and, afterward, trudged to the library and then rode home with my geologist father. … Mostly, I read.”

After Rebecca Knuth retired from an academic career in library and information science, she moved to London for a master’s degree in creative nonfiction and joined the London Library as well as the public library. But in her memoir London Sojourn (coming out in January), she recalls that she caught the library bug early: “Each weekday, I bused to school and, afterward, trudged to the library and then rode home with my geologist father. … Mostly, I read.”

And in Joyride, Susan Orlean recounts the writing of each of her books, including The Library Book, which is about the 1986 arson at the Los Angeles Central Library but also, more widely, about what libraries have to offer and the oddballs often connected with them.

And in Joyride, Susan Orlean recounts the writing of each of her books, including The Library Book, which is about the 1986 arson at the Los Angeles Central Library but also, more widely, about what libraries have to offer and the oddballs often connected with them.

My library use over the last month:

(links are to any reviews of books not already covered on the blog)

READ

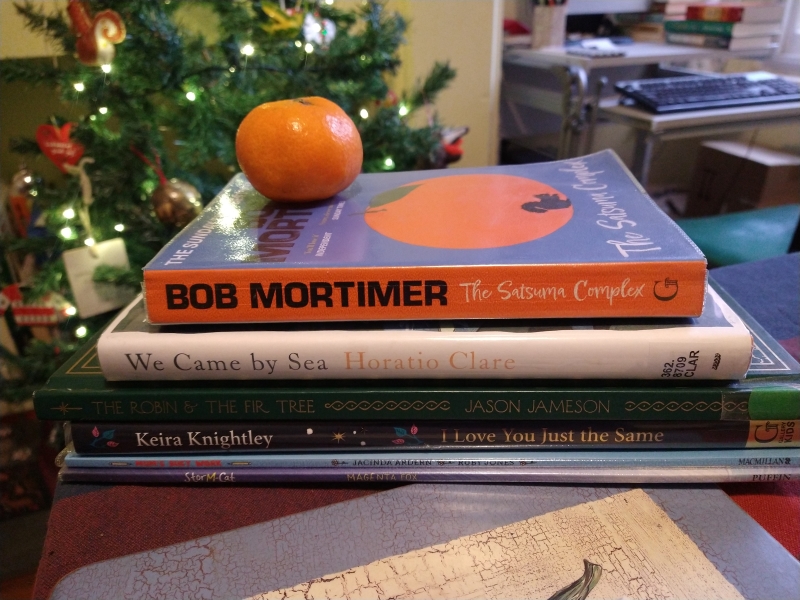

- Mum’s Busy Work by Jacinda Ardern; illus. Ruby Jones

- Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood

- Storm-Cat by Magenta Fox

- The Robin & the Fir Tree by Jason Jameson

- I Love You Just the Same by Keira Knightley – Proof that celebrities should not be writing children’s books. I would say the story and drawings were pretty good … if she were a college student.

- Winter by Val McDermid

- The Search for the Giant Arctic Jellyfish, The Search for Carmella, & The Search for Our Cosmic Neighbours by Chloe Savage

- Weirdo Goes Wild by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird; illustrated by Magenta Fox

- Murder Most Unladylike by Robin Stevens

+ A final contribution to #DoorstoppersInDecember

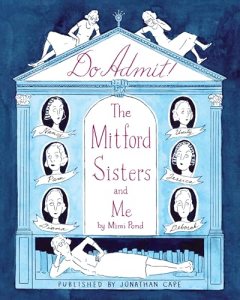

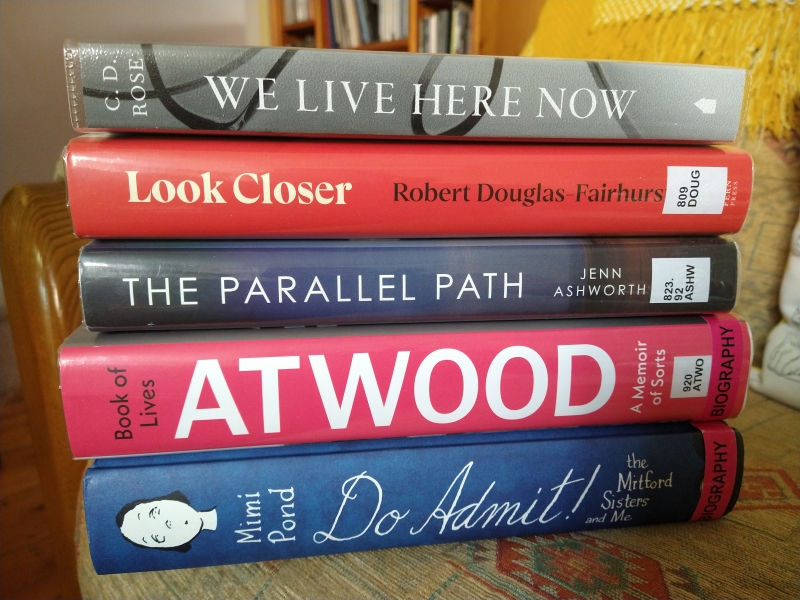

Do Admit: The Mitford Sisters and Me by Mimi Pond

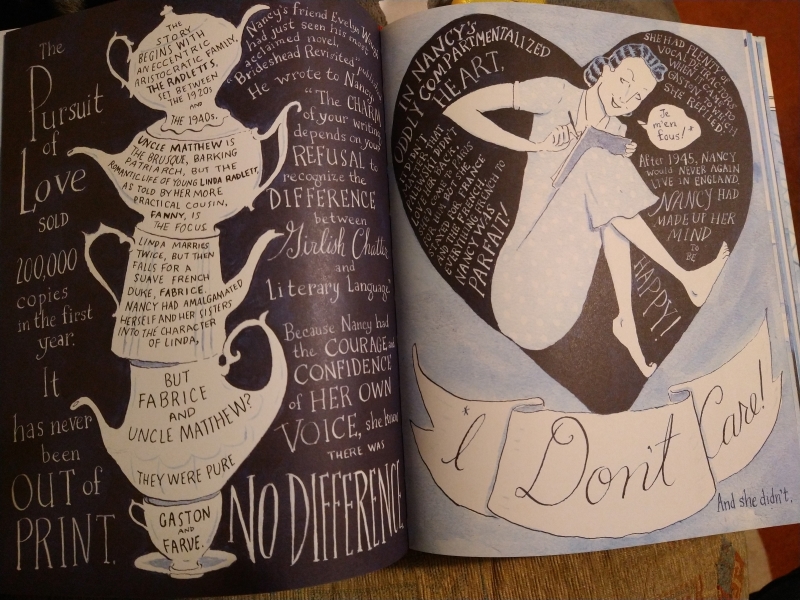

Truth really is stranger than fiction. Of the six Mitford sisters, two were fascists (Diana and Unity) and one was a communist (Jessica). Two became popular authors (Nancy and Jessica). One (Unity) was pals with Hitler and shot herself in the head when Britain went to war with Germany; she didn’t die then but nine years later of an infection from the bullet still stuck in her brain. This is all rich fodder for a biographer – the batshit lives of the rich and famous are always going to fascinate us peons – and Pond’s comics treatment is a great way of keeping history from being one boring event after another. Although she uses the same Prussian blue tones throughout, she mixes up the format, sometimes employing 3–5 panes but often choosing to create one- or two-page spreads focusing on a face, a particular setting or a montage. No two pages are exactly alike and information is conveyed through dialogue, documents and quotations. If just straight narrative, there are different typefaces or text colours and it is interspersed with the pictures in a novel way. Whether or not you know a thing about the Mitfords, the book intrigues with its themes of family dynamics, grief, political divisions, wealth and class. My only misgiving, really, was about the “and Me” part of the title; Pond appears in maybe 5% of the book, and the only personal connections I gleaned were that she wished she had sisters, wanted to escape, and envied privilege and pageantry. [444 pages]

Truth really is stranger than fiction. Of the six Mitford sisters, two were fascists (Diana and Unity) and one was a communist (Jessica). Two became popular authors (Nancy and Jessica). One (Unity) was pals with Hitler and shot herself in the head when Britain went to war with Germany; she didn’t die then but nine years later of an infection from the bullet still stuck in her brain. This is all rich fodder for a biographer – the batshit lives of the rich and famous are always going to fascinate us peons – and Pond’s comics treatment is a great way of keeping history from being one boring event after another. Although she uses the same Prussian blue tones throughout, she mixes up the format, sometimes employing 3–5 panes but often choosing to create one- or two-page spreads focusing on a face, a particular setting or a montage. No two pages are exactly alike and information is conveyed through dialogue, documents and quotations. If just straight narrative, there are different typefaces or text colours and it is interspersed with the pictures in a novel way. Whether or not you know a thing about the Mitfords, the book intrigues with its themes of family dynamics, grief, political divisions, wealth and class. My only misgiving, really, was about the “and Me” part of the title; Pond appears in maybe 5% of the book, and the only personal connections I gleaned were that she wished she had sisters, wanted to escape, and envied privilege and pageantry. [444 pages] ![]()

CURRENTLY READING

- The Parallel Path: Love, Grit and Walking the North by Jenn Ashworth

- The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier

- Of Thorn & Briar: A Year with the West Country Hedgelayer by Paul Lamb

- The Satsuma Complex by Bob Mortimer (for book club in January; I’m grumpy about it because I didn’t vote for this one, had no idea who the author [a TV comedian in the UK] was, and the writing is shaky at best)

- We Live Here Now by C.D. Rose

SKIMMED

- Look Closer: How to Get More out of Reading by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- It’s Not a Bloody Trend: Understanding Life as an ADHD Adult by Kat Brown

- We Came by Sea by Horatio Clare

ON HOLD, TO BE COLLECTED

- The Two Faces of January by Patricia Highsmith

- Arsenic for Tea by Robin Stevens

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Honour & Other People’s Children by Helen Garner

- Snegurochka by Judith Heneghan

- Ultra-Processed People by Dr. Chris van Tulleken (for book club in February)

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Night Life: Walking Britain’s Wild Landscapes after Dark by John Lewis-Stempel

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

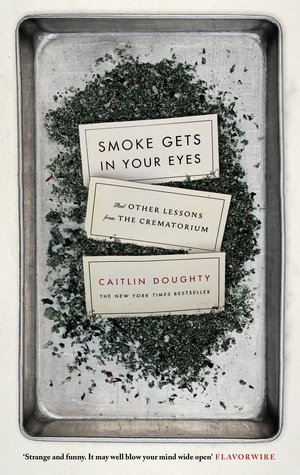

Review: Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, by Caitlin Doughty

Caitlin Doughty, a funeral director in her early thirties, is on a mission. Her goal? Nothing less than completely changing how we think about death and the customs surrounding it. Her odyssey through the death industry began when she was 23 and started working at suburban San Francisco’s Westwind Crematorium. She had spent her first 18 years in Hawaii and saw her first dead body at age eight when she went to a Halloween costume contest at the mall and saw a little girl plummet 30 feet over a railing. In another century, she reflects, it would have been rare for a child to go that long before seeing a corpse; nineteenth-century tots might have experienced the death of multiple siblings, if not a parent.

Caitlin Doughty, a funeral director in her early thirties, is on a mission. Her goal? Nothing less than completely changing how we think about death and the customs surrounding it. Her odyssey through the death industry began when she was 23 and started working at suburban San Francisco’s Westwind Crematorium. She had spent her first 18 years in Hawaii and saw her first dead body at age eight when she went to a Halloween costume contest at the mall and saw a little girl plummet 30 feet over a railing. In another century, she reflects, it would have been rare for a child to go that long before seeing a corpse; nineteenth-century tots might have experienced the death of multiple siblings, if not a parent.

“Today, not being forced to see corpses is a privilege of the developed world,” she writes. And if we do see a dead body, it will have been so prettified by mortuary workers that it might bear little resemblance to how the person looked in life. Here Doughty reveals all the tricks of the American trade – from embalming (a post-Civil War development) and heavy-duty makeup to gluing eyes closed and sewing mouths shut – that give the dead that peaceful, lifelike look we like to see at wakes. Compare our squeamishness with the openness of various Asian countries, where one might see dozens of corpses floating down the Ganges or Buddhist monks meditating on a decomposing corpse as a memento mori.

Doughty is in a somewhat awkward position: she is part of the very American death industry she is criticizing – those “professionals whose job was not ritual but obfuscation, hiding the truths of what bodies are and what bodies do.” Although she reveled in her work at the crematorium despite its occasional gruesomeness and seems to believe cremation is an efficient and responsible choice for body disposal, she also worries that it might be a further sign of people’s determination to keep bodies out of sight and out of mind. As anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer noted, “In many cases, it would appear, cremation is chosen because it is felt to get rid of the dead more completely and finally than does burial.”

Could cremation be noble instead? Doughty traces its origins to ancient Roman funeral pyres, as different as could be from the enclosed, clinical environment of a modern crematorium. Two factors led directly to cremation becoming increasingly accepted and popular after the 1960s. One was Jessica Mitford’s book The American Way of Death (1961), which mocked the same Los Angeles area cemetery Evelyn Waugh does in The Loved One, Forest Lawn. The other was Pope Paul VI overturning the Catholic Church’s ban on cremation in 1963. Doughty quotes George Bernard Shaw’s rapturous account of his mother’s cremation in 1913 as proof that it can be not only natural, but even aesthetically pleasing:

And behold! The feet burst miraculously into streaming ribbons of garnet colored lovely flame, smokeless and eager, like Pentecostal tongues, and as the whole coffin passed in it sprang into flame all over, and my mother became that beautiful fire.

It is rare, however – and, for the workers, nerve-racking – to have witnesses at a cremation. For the most part Westwind worked like a factory, cremating six bodies per weekday. Doughty experienced all sides of the work: collecting dead fetuses from hospitals for free cremation, shaving adult corpses before burning, enduring the stench of decomposing flesh, and taking delivery of a box of heads whose bodies were donated to science. She is largely unsentimental about it all; who is this fairytale witch who speaks of “tossing” babies into the oven and grinding their little bones?

“Handmaiden to the underworld,” she describes herself, and given her medieval history degree and Goth-lite looks, you can see that a certain macabre cast of mind is necessary for this line of work. She also has a good ear for arrestingly witty one-liners; my favorite was “As a general rule, if anyone ever asks you to put stockings on a ninety-year-old deceased Romanian woman with edema, your answer should be no.”

Still, Doughty recognizes the almost unbearable sadness of many of the cases the crematorium sees – the young man who traveled to California from Washington just to stand in the path of a train, the “floaters” found in the ocean, the elderly with oozing bed sores, and the homeless folk of Los Angeles who were cremated and dumped in a mass grave after they were used for embalming practice at her mortuary school. She even considered committing suicide herself on a lonely trip out to a redwood forest.

What has kept her going is the desire to combat misconceptions and superstitions about the dead. As she realized after a potentially serious car accident on the freeway, she has lost her own fear of death, and she wants to help others do the same. This will require getting people talking about death, something she is doing through her online community Order of the Good Death and her Ask a Mortician YouTube videos. She would also like to see people having involvement with dead bodies again, as they did in previous centuries, perhaps by washing their dead relatives or keeping them at home before the funeral rather than having them taken away. “It is never too early to start thinking about your own death and the deaths of those you love.” This is not morbid; it’s just planning ahead for an inevitable experience. “We can wander further into the death dystopia, denying that we will die and hiding dead bodies from our sight. Making that choice means we will continue to be terrified and ignorant of death, and the huge role it plays in how we live our lives.”

The sections of personal anecdote in this book are better than those based on anthropological research – which is not woven in entirely naturally. Ultimately, it’s a little unclear exactly how Doughty plans to change things. She speaks of designing her own welcoming crematorium, an open, airy space that doesn’t suggest a death factory. But it’s enough that she’s part of a movement in the right direction, and beneath her wry tone her passion is clear.

Further reading suggestions: For more on how people are revolutionizing how we think about death, I highly recommend Anne Karpf’s book for the School of Life, How to Age. Other death-themed reads I have particularly enjoyed are The Undertaking by Thomas Lynch, The Removers by Andrew Meredith, and A Tour of Bones by Denise Inge. Less effective as a memoir but still interesting for its view of the funeral home business is The Undertaker’s Daughter by Kate Mayfield.

Note: I was originally going to review this book for a British website, so I received a free copy of the UK edition from Canongate. Doughty inserts British statistics and information to increase the book’s relevance to a new audience. She also astutely notes that British funerals minimize interaction with a dead body, something I have certainly found true in the two cremations I have attended in England. The Irish are famous for their wakes, but the British do not have this custom. In fact, when we attended my brother-in-law’s viewing and funeral in America earlier this year, it was the first time my husband (aged 31) had seen a dead body. Although I can see Doughty’s point about a prettified corpse not being representative of what the dead ‘should’ look like, I must also say that the funeral home had done a fantastic job of making him look happy and at peace, like he was sleeping and having pleasant dreams. He certainly didn’t look like a man who had suffered the ravages of brain cancer for four years. The same was not true for my ninety-something grandmother, however, who was nearly unrecognizable.