Interview with Neil Griffiths of Weatherglass Books (#NovNov24)

Back in September, I attended a great “The Future of the Novella” event in London, hosted by Weatherglass. I wrote about it here, and earlier this month I reviewed the first of the two winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, Astraea by Kate Kruimink*. Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths kindly sent review copies of both winning books, and agreed to answer some questions over e-mail.

Back in September, I attended a great “The Future of the Novella” event in London, hosted by Weatherglass. I wrote about it here, and earlier this month I reviewed the first of the two winners of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, Astraea by Kate Kruimink*. Weatherglass Books co-founder and novelist Neil Griffiths kindly sent review copies of both winning books, and agreed to answer some questions over e-mail.

Samantha Harvey’s 136-page Orbital won the Booker Prize, the film adaptation of Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These is in cinemas: Is the novella having a moment? If so, how do you account for its fresh prominence? Or has it always been a powerful form and we’re realizing it anew?

I do wonder whether Orbital is a novella, by which I mean, number of pages can be deceptive – there are a lot of words per page! I think it probably sneaks in under our Novella Prize max word count: under 40K. Also, I wonder whether Small Things like These would make it over our minimum 20K. I don’t think so. But what I think we can say is that there is something happening around length.

I do wonder whether Orbital is a novella, by which I mean, number of pages can be deceptive – there are a lot of words per page! I think it probably sneaks in under our Novella Prize max word count: under 40K. Also, I wonder whether Small Things like These would make it over our minimum 20K. I don’t think so. But what I think we can say is that there is something happening around length.

My co-founder of Weatherglass, Damian Lanigan, says this: “the novella is the form for our times: befitting our short attention spans, but also with its tight focus, with its singular atmosphere – it’s the ideal form for glimpsing something essential about the world and ourselves in an increasingly chaotic world.”

But then if we look over the history of the prose fiction over the last 200 hundred years, there are so many novellas that have defined an era: Turgenev’s Love, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Carr’s A Month in the Country, Orwell’s Animal Farm, Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Why did Weatherglass choose to focus on short books? Do economic and environmental factors come into it (short books = less paper = lower printing costs as well as fewer trees cut down)?

Economic and environmental factors play a role, but there is also craft. Writers need to ask themselves the question: does this story need to be this length, and the answer is, more often than not: no. I think constraints bring the best out of writers. If a novel comes in at 70K words, our first thought is to cut 10K. (I should say, my last novel, very kindly reviewed by yourself, was a whooping 190K words. It should have been 150K! Since then I’ve written two pieces of fiction, both under 35K.)

Economic and environmental factors play a role, but there is also craft. Writers need to ask themselves the question: does this story need to be this length, and the answer is, more often than not: no. I think constraints bring the best out of writers. If a novel comes in at 70K words, our first thought is to cut 10K. (I should say, my last novel, very kindly reviewed by yourself, was a whooping 190K words. It should have been 150K! Since then I’ve written two pieces of fiction, both under 35K.)

Neil Griffiths

We’ve heard about the bloating of films, that they’re something like 20% longer on average than they were 40 years ago; will books take the opposite trajectory? Can a one-sitting read compete with a film?

I don’t think I’ve ever read even the shortest novella in one sitting. I need time to reflect. I don’t think comparing the two forms is helpful because they require different things of us. Take music: Morton Feldman’s 2nd String Quartet is 5 hours long, without a break. I’d commit to that in the concert hall, but I couldn’t read for 5 hours without a break or sit through a film.

How did you bring Ali Smith on board as the judge for the first two years of the Weatherglass Novella Prize? There was a blind judging process and you ended up with an all-female shortlist in the inaugural year. Do you have a theory as to why?

Ali Smith

Damian kept saying Ali Smith would be the best judge and I kept saying “but how do we get to her?” Then someone told me they had her email address. I didn’t expect to get an answer. A ‘Yes’ came an hour later. She’s been wonderful to work with. And she’s enjoyed it so much she’s agreed to do it ongoingly.

I do think the shortlist question is an important one. Certainly we don’t have to ask ourselves any questions when it’s an all-female short list, but we would if it was all-male. What does that say? I don’t know why the strongest were by women.

Do you have any personal favourite novellas?

A Month in the Country might be the exemplar of the form for me. But there is a little-read novella by Tolstoy, Hadji Murat, which is also close to perfect. More contemporaneously, Gerald Murnane’s Border Districts. And I’m pleased to say: all three novellas we’re publishing from our inaugural prize are up there: Astraea, Aerth and We Hexed the Moon.

A Month in the Country might be the exemplar of the form for me. But there is a little-read novella by Tolstoy, Hadji Murat, which is also close to perfect. More contemporaneously, Gerald Murnane’s Border Districts. And I’m pleased to say: all three novellas we’re publishing from our inaugural prize are up there: Astraea, Aerth and We Hexed the Moon.

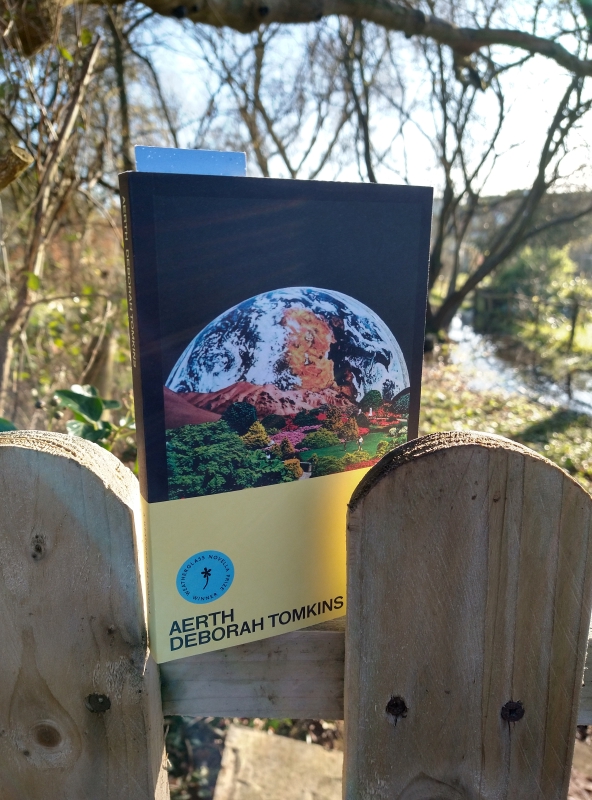

*Though it won’t be published until 25 January, I have a finished copy of the other winner, Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, a novella-in-flash set on alternative earths and incorporating second- and third-person narration and various formats. I’ve been enjoying it so far and hope to review it soon as my first recommendation for 2025.

Astraea by Kate Kruimink (Weatherglass Novella Prize) #NovNov24

Astraea by Kate Kruimink is one of two winners* of the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize, as chosen by Ali Smith. Back in September, I was introduced to it through Weatherglass Books’ “The Future of the Novella” event in London (my write-up is here).

Taking place within about a day and a half on a 19th-century convict ship bound for Australia, it is the intense story of a group of women and children chafing against the constraints men have set for them. The protagonist is just 15 years old and postpartum. Within a hostile environment, the women have created an almost cosy community based on sisterhood. They look out for each other; an old midwife can still bestow her skills.

The ship was their shelter, the small chalice carrying them through that which was inhospitable to human life. But there was no shelter for her there, she thought. There was only a series of confines between which she might move but never escape.

The ship’s doctor and chaplain distrust what they call the “conspiracy of women” and are embarrassed by the bodily reality of one going into labour, another tending to an ill baby, and a third haemorrhaging. They have no doubt they know what is best for their charges yet can barely be bothered to learn their names.

Indeed, naming is key here. The main character is effectively erased from the historical record when a clerk incorrectly documents her as Maryanne Maginn. Maryanne’s only “maybe-friend,” red-haired Sarah, has the surname Ward. “Astraea” is the name not just of the ship they travel on but also of a star goddess and a new baby onboard.

The drama in this novella arises from the women’s attempts to assert their autonomy. Female rage and rebellion meet with punishment, including a memorable scene of solitary confinement. A carpenter then constructs a “nice little locking box that will hold you when you sin, until you’re sorry for it and your souls are much recovered,” as he tells the women. They are all convicts, and now their discipline will become a matter of religious theatrics.

Given the limitations of setting and time and the preponderance of dialogue, I could imagine this making a powerful play. The novella length is as useful a framework as the ship itself. Kruimink doesn’t waste time on backstory; what matters is not what these women have done to end up here, but how their treatment is an affront to their essential dignity. Even in such a low page count, though, there are intriguing traces of the past and future, as well as a fleeting hint of homoeroticism. I would recommend this to readers of The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave, Devotion by Hannah Kent and Women Talking by Miriam Toews. And if you get a hankering to follow up on the story, you can: this functions as a prequel to Kruimink’s first novel, A Treacherous Country. (See also Cathy’s review.)

[115 pages]

With thanks to Weatherglass Books for the free copy for review.

*The other winner, Aerth by Deborah Tomkins, a novella-in-flash set on alternative earths, will be published in January. I hope to have a proof copy in hand before the end of the month to review for this challenge plus SciFi Month.

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler,” as Joe Hill said. Hard to believe, but it’s now the FIFTH year that Cathy of 746 Books and I have been co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long blogger/social media challenge celebrating the art of the short book. A novella is a book of 20,000 to 40,000 words, but because that’s hard for a reader to gauge, we tend to say anything under 200 pages (even nonfiction). I’m going to make it a personal challenge to limit myself to books of ~150 pages or less.

We’re keeping it simple this year with just the one buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey. (Though we chose it weeks ago, its shortlisting for the Booker Prize is all the more reason to read it!) The UK hardback has 144 pages. Here’s part of the blurb to entice you:

“Six astronauts rotate in their spacecraft above the earth. … Together they watch their silent blue planet, circling it sixteen times, spinning past continents and cycling through seasons, taking in glaciers and deserts, the peaks of mountains and the swells of oceans. Endless shows of spectacular beauty witnessed in a single day. Yet although separated from the world they cannot escape its constant pull. News reaches them of the death of a mother, and with it comes thoughts of returning home. … They begin to ask, what is life without earth? What is earth without humanity?”

Please join us in reading it at any time between now and the end of November!

We won’t have any official themes or prompts, but you might want to start off the month with a My Year in Novellas retrospective looking at any novellas you have read since last NovNov, and finish it with a New to My TBR list based on what novellas others have tempted you to try in the future.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Margaret Atwood Reading Month and SciFi Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that could count towards multiple challenges?

From 1 November there will be a pinned post on my site from which you can join the link-up. Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books), and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov24.

“The Future of the Novella”

On the 11th, at Foyles in London, I attended a perfect event to get me geared up for Novellas in November. Indie publisher Weatherglass Books and judge Ali Smith introduced us to the two winners she chose for the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize: Kate Kruimink’s Astraea (set on a 19th-century Australian convict ship), out now, and Deborah Tomkins’ Aerth (a sci-fi novella in flash set on alternative earths), coming out in January.

Ali Smith

We heard readings from both novellas, and Neil Griffiths and Damian Lanigan of Weatherglass told us some more about what they publish and the process of reading the prize submissions (blind!). Lanigan called the novella “a form for our times” and put this down not just to modern attention spans but to focus – the glimpse of something essential. He and Smith mentioned F. Scott Fitzgerald, Claire Keegan, Françoise Sagan and Muriel Spark as some of the masters of the novella form.

The effortlessly cool Smith spoke about the delight of spending weekend mornings – she writes during the week but gives herself the weekends off to read – in bed with a pot of coffee and a Weatherglass novella. She particularly enjoyed going into each book from the shortlist without any context and lamented that blurbs mean the story has to be, to some extent, given away to the reader. She said the ending of a novella has to land “like a cat, on its feet” (Griffiths then appended that it must also be ambiguous).

Kate Kruimink

Kruimink, who edits short stories for a magazine, explained that she thinks of Astraea as a long short story. She wrote it especially for this prize, within two months and for Ali Smith, as it were (she mentioned how formative How to Be Both was for her as a writer). Due to time and word limit constraints, she deliberately crafted a small character arc and didn’t do loads of research, though she had been looking into ships’ surgeons’ journals at the time. She has Irish convict ancestry but noted that this is not uncommon in Tasmania. Astraea is a “sneaky prequel” to her first novel, which has been published in Australia.

Deborah Tomkins

Aerth was originally titled First, Do No Harm, which had the potential to confuse those looking for a medical read. Aerth and Urth are different planets with parallels to our own. The novella tells the story of Magnus, an Everyman on a deeply forested planet heading into an Ice Age. Tomkins first wrote it for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted, then added to it. She initially sent the book to sci-fi publishers but was told it was not ‘sci-fi enough’.

Griffiths remarked that the shortlist was all-female and that the two winners show how a novella can do many different things: Astraea is at the low end of the word count at 22,000 words and takes place over just 36 hours; Aerth is towards the upper limit at 36,000 words and spans about 40 years.

Neil Griffiths

All the panellists dismissed the idea of a hierarchy with the full-length novel at the top. Griffiths said that the constraints of the novella, to need to discard and discard, make it stand out.

A further title from the 2024 shortlist, We Hexed the Moon by Mollyhall Seeley, will also be published by Weatherglass next year, and submissions are now open for the Weatherglass Novella Prize 2025.

Many thanks for my free ticket to a great event. Weatherglass has also kindly offered to send Cathy and me copies of the two novellas to review over the course of #NovNov. I’m looking forward to reading both winners!