#NonFicNov: Being the Expert on Covid Diaries

This year the Be/Ask/Become the Expert week of the month-long Nonfiction November challenge is hosted by Veronica of The Thousand Book Project. (In previous years I’ve contributed lists of women’s religious memoirs (twice), accounts of postpartum depression, and books on “care”.)

I’ve been devouring nonfiction responses to COVID-19 for over a year now. Even memoirs that are not specifically structured as diaries take pains to give a sense of what life was like from day to day during the early months of the pandemic, including the fear of infection and the experience of lockdown. Covid is mentioned in lots of new releases these days, fiction or nonfiction, even if just via an introduction or epilogue, but I’ve focused on books where it’s a major element. At the end of the post I list others I’ve read on the theme, but first I feature four recent releases that I was sent for review.

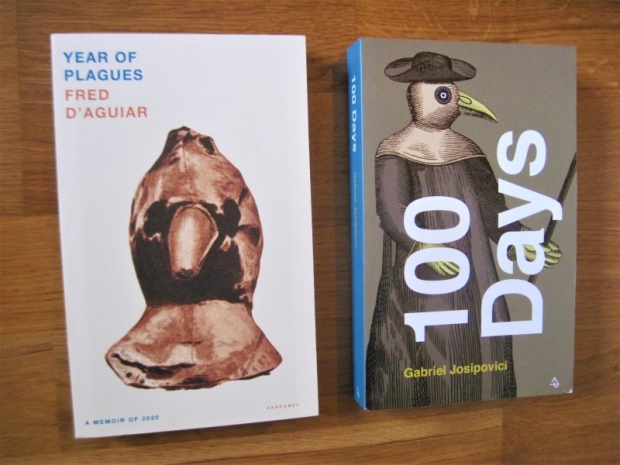

Year of Plagues: A Memoir of 2020 by Fred D’Aguiar

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

Cancer needs a song: tambourine and cymbals and a choir, not to raise it from the dead but [to] lay it to rest finally.

Tracing the effects of his cancer on his wife and children as well as on his own body, he wonders if the treatment will disrupt his sense of his own masculinity. I thought the narrative would hit home given that I have a family member going through the same thing, but it struck me as a jumble, full of repetition and TMI moments. Expecting concision from a poet, I wanted the highlights reel instead of 323 rambling pages.

(Carcanet Press, August 26.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Still, I appreciated Josipovici’s thoughts on literature and his own aims for his work (more so than the rehashing of Covid statistics and official briefings from Boris Johnson et al., almost unbearable to encounter again):

In my writing I have always eschewed visual descriptions, perhaps because I don’t have a strong visual memory myself, but actually it is because reading such descriptions in other people’s novels I am instantly bored and feel it is so much dead wood.

nearly all my books and stories try to force the reader (and, I suppose, as I wrote, to force me) to face the strange phenomenon that everything does indeed pass, and that one day, perhaps sooner than most people think, humanity will pass and, eventually, the universe, but that most of the time we live as though all was permanent, including ourselves. What rich soil for the artist!

Why have I always had such an aversion to first person narratives? I think precisely because of their dishonesty – they start from a falsehood and can never recover. The falsehood that ‘I’ can talk in such detail and so smoothly about what has ‘happened’ to ‘me’, or even, sometimes, what is actually happening as ‘I’ write.

You never know till you’ve plunged in just what it is you really want to write. When I started writing The Inventory I had no idea repetition would play such an important role in it. And so it has been all through, right up to The Cemetery in Barnes. If I was a poet I would no doubt use refrains – I love the way the same thing becomes different the second time round

To write a novel in which nothing happens and yet everything happens: a secret dream of mine ever since I began to write

I did sense some misogyny, though, as it’s generally female writers he singles out for criticism: Iris Murdoch is his prime example of the overuse of adjectives and adverbs, he mentions a “dreadful novel” he’s reading by Elizabeth Bowen, and he describes Jean Rhys and Dorothy Whipple as women “who, raised on a diet of the classic English novel, howled with anguish when life did not, for them, turn out as they felt it should.”

While this was enjoyable to flip through, it’s probably more for existing fans than for readers new to the author’s work, and the Covid connection isn’t integral to the writing experiment.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

A stanza from the below collection to link the first two books to this next one:

Have they found him yet, I wonder,

whoever it is strolling

about as a plague doctor, outlandish

beak and all?

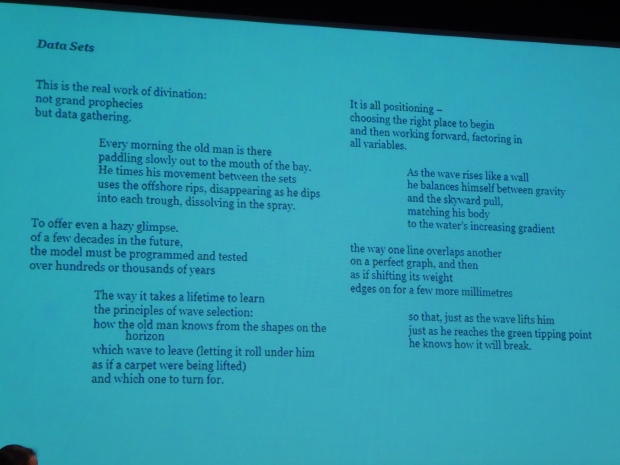

The Crash Wake and Other Poems by Owen Lowery

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

As the seventh anniversary of his wedding to Jayne nears, Lowery reflects on how love has kept him going despite flashbacks to the accident and feeling written off by his doctors. In the second section of the book, the subjects vary from the arts (Paula Rego’s photographs, Stanley Spencer’s paintings, R.S. Thomas’s theology) to sport. There is also a lovely “Remembrance Day Sequence” imagining what various soldiers, including Edward Thomas and his own grandfather, lived through. The final piece is a prose horror story about a magpie. Like a magpie, I found many sparkly gems in this wide-ranging collection.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free e-copy for review.

Behind the Mask: Living Alone in the Epicenter by Kate Walter

[135 pages, so I’m counting this one towards #NovNov, too]

For Walter, a freelance journalist and longtime Manhattan resident, coronavirus turned life upside down. Retired from college teaching and living in Westbeth Artists Housing, she’d relied on activities outside the home for socializing. To a single extrovert, lockdown offered no benefits; she spent holidays alone instead of with her large Irish Catholic family. Even one of the world’s great cities could be a site of boredom and isolation. Still, she gamely moved her hobbies onto Zoom as much as possible, and welcomed an escape to Jersey Shore.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

There’s a lot here to relate to – being glued to the news, anxiety over Trump’s possible re-election, looking forward to vaccination appointments – and the book is also revealing on the special challenges for older people and those who don’t live with family. However, I found the whole fairly repetitive (perhaps as a result of some pieces originally appearing in The Village Sun and then being tweaked and inserted here).

Before an appendix of four short pre-Covid essays, there’s a section of pandemic writing prompts: 12 sets of questions to use to think through the last year and a half and what it’s meant. E.g. “Did living through this extraordinary experience change your outlook on life?” If you’ve been meaning to leave a written record of this time for posterity, this list would be a great place to start.

(Heliotrope Books, November 16.) With thanks to the publicist for the free e-copy for review.

Other Covid-themed nonfiction I have read:

Medical accounts

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

- Intensive Care by Gavin Francis

- Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer and Dan Koeppel (reviewed for Shelf Awareness)

- Duty of Care by Dominic Pimenta

- Many Different Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen

+ I have a proof copy of Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki, coming out in January.

Nature writing

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

- The Heeding by Rob Cowen (in poetry form)

- Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt

- The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren

- Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss

General responses

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

- The Rome Plague Diaries by Matthew Kneale

- Quarantine Comix by Rachael Smith (in graphic novel form; reviewed for Foreword Reviews)

- UnPresidented by Jon Sopel

+ on my Kindle: Alone Together, an anthology of personal essays

+ on my TBR: What Just Happened: Notes on a Long Year by Charles Finch

If you read just one… Make it Intensive Care by Gavin Francis. (And, if you love nature books, follow that up with The Consolation of Nature.)

Can you see yourself reading any of these?

Recent Reviews for Shiny New Books: Poetry, Fiction and Nature Writing

First up was a rundown of my five favorite poetry releases of the year, starting with…

Dearly by Margaret Atwood

Dearly is a treasure trove, twice the length of the average poetry collection and rich with themes of memory, women’s rights, environmental crisis, and bereavement. It is reflective and playful, melancholy and hopeful. I can highly recommend it, even to non-poetry readers, because it is led by its themes; although there are layers to explore, these poems are generally about what they say they’re about, and more material than abstract. Alliteration, repetition, internal and slant rhymes, and neologisms will delight language lovers and make the book one to experience aloud as well as on paper. Atwood’s imagery ranges from the Dutch masters to The Wizard of Oz. Her frame of reference is as wide as the array of fields she’s written in over the course of over half a century.

Dearly is a treasure trove, twice the length of the average poetry collection and rich with themes of memory, women’s rights, environmental crisis, and bereavement. It is reflective and playful, melancholy and hopeful. I can highly recommend it, even to non-poetry readers, because it is led by its themes; although there are layers to explore, these poems are generally about what they say they’re about, and more material than abstract. Alliteration, repetition, internal and slant rhymes, and neologisms will delight language lovers and make the book one to experience aloud as well as on paper. Atwood’s imagery ranges from the Dutch masters to The Wizard of Oz. Her frame of reference is as wide as the array of fields she’s written in over the course of over half a century.

I’ll let you read the whole article to discover my four runners-up. (They’ll also be appearing in my fiction & poetry best-of post next week.)

Next was one of my most anticipated reads of the second half of 2020. (I was drawn to it by Susan’s review.)

Artifact by Arlene Heyman

Lottie’s story is a case study of the feminist project to reconcile motherhood and career (in this case, scientific research). In the generic more than the scientific meaning of the word, the novel is indeed about artifacts – as in works by Doris Lessing, Penelope Lively and Carol Shields, the goal is to unearth the traces of a woman’s life. The long chapters are almost like discrete short stories. Heyman follows Lottie through years of schooling and menial jobs, through a broken marriage and a period of single parenthood, and into a new relationship. There were aspects of the writing that didn’t work for me and I found the book as a whole more intellectually noteworthy than engaging as a story. A piercing – if not notably subtle – story of women’s choices and limitations in the latter half of the twentieth century. I’d recommend it to fans of Forty Rooms and The Female Persuasion.

Lottie’s story is a case study of the feminist project to reconcile motherhood and career (in this case, scientific research). In the generic more than the scientific meaning of the word, the novel is indeed about artifacts – as in works by Doris Lessing, Penelope Lively and Carol Shields, the goal is to unearth the traces of a woman’s life. The long chapters are almost like discrete short stories. Heyman follows Lottie through years of schooling and menial jobs, through a broken marriage and a period of single parenthood, and into a new relationship. There were aspects of the writing that didn’t work for me and I found the book as a whole more intellectually noteworthy than engaging as a story. A piercing – if not notably subtle – story of women’s choices and limitations in the latter half of the twentieth century. I’d recommend it to fans of Forty Rooms and The Female Persuasion.

Finally, I contributed a dual review of two works of nature writing that would make perfect last-minute Christmas gifts for outdoorsy types and/or would be perfect bedside books for reading along with the English seasons into a new year.

The Stubborn Light of Things by Melissa Harrison

This collects five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. The book falls into two rough halves, “City” and “Country”: initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. Often, she need look no further than her own home and garden. I appreciated how hands-on and practical she is: She’s always picking up dead animals to clean up and display the skeletons, and she never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife (e.g. bat and bird nest boxes that can be incorporated into buildings) and get involved in citizen science projects like moth recording.

This collects five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. The book falls into two rough halves, “City” and “Country”: initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. Often, she need look no further than her own home and garden. I appreciated how hands-on and practical she is: She’s always picking up dead animals to clean up and display the skeletons, and she never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife (e.g. bat and bird nest boxes that can be incorporated into buildings) and get involved in citizen science projects like moth recording.

The book’s final two entries were set during the UK’s first COVID-19 lockdown in spring 2020 – a notably fine season. This inspired me to review it alongside…

The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren

A tripartite diary of the coronavirus spring kept by three veteran nature writers based in southern England (all of them familiar to me through their involvement with New Networks for Nature and its annual Nature Matters conferences). The entries, of a similar length to Harrison’s, are grouped into chronological chapters from 21 March to 31 May. While the authors focus in these 10 weeks on their wildlife sightings – red kites, kestrels, bluebells, fungal fairy rings and much more – they also log government advice and death tolls. They achieve an ideal balance between current events and the timelessness of nature, enjoyed all the more in 2020’s unprecedented spring because of a dearth of traffic noise.

A tripartite diary of the coronavirus spring kept by three veteran nature writers based in southern England (all of them familiar to me through their involvement with New Networks for Nature and its annual Nature Matters conferences). The entries, of a similar length to Harrison’s, are grouped into chronological chapters from 21 March to 31 May. While the authors focus in these 10 weeks on their wildlife sightings – red kites, kestrels, bluebells, fungal fairy rings and much more – they also log government advice and death tolls. They achieve an ideal balance between current events and the timelessness of nature, enjoyed all the more in 2020’s unprecedented spring because of a dearth of traffic noise.

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.)

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.) Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.) Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!)

Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!) Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

Sarah Bennett, who went straight from university in Oxford to Paris for want of a better idea of what to do with her life, is called home to Warwickshire to be a bridesmaid in the wedding of her older sister, Louise, to Stephen Halifax, a wealthy novelist. Afterwards, Sarah decides to move to London and share a flat with a friend whose marriage has recently ended. As the months pass, she figures out life as a single girl in a big city and attends parties hosted by Louise – back from an extended European honeymoon – and others. Sarah eventually works out, from gossip and from confronting Louise herself, that her sister’s marriage isn’t as idyllic as it appeared. Both sisters find themselves at a loss as for what to do next.

Sarah Bennett, who went straight from university in Oxford to Paris for want of a better idea of what to do with her life, is called home to Warwickshire to be a bridesmaid in the wedding of her older sister, Louise, to Stephen Halifax, a wealthy novelist. Afterwards, Sarah decides to move to London and share a flat with a friend whose marriage has recently ended. As the months pass, she figures out life as a single girl in a big city and attends parties hosted by Louise – back from an extended European honeymoon – and others. Sarah eventually works out, from gossip and from confronting Louise herself, that her sister’s marriage isn’t as idyllic as it appeared. Both sisters find themselves at a loss as for what to do next.

Another sisters novel, and the first book in my

Another sisters novel, and the first book in my

In 2009, Barkham set out to revive the childhood butterfly-watching hobby he’d shared with his father. The UK is home to 59 species, a manageable number to attempt to see in a season, although it does require a fair bit of travel and insider knowledge. I’ve read too much general history about the human relationship with butterflies (via Rainbow Dust by Peter Marren, which came out a few years later, and

In 2009, Barkham set out to revive the childhood butterfly-watching hobby he’d shared with his father. The UK is home to 59 species, a manageable number to attempt to see in a season, although it does require a fair bit of travel and insider knowledge. I’ve read too much general history about the human relationship with butterflies (via Rainbow Dust by Peter Marren, which came out a few years later, and  They encountered Morris dancers, gypsies, hippies at Stonehenge for the Summer Solstice, sisters having a double wedding, and magic mushroom collectors. They went to a county fair and beaches in Suffolk and East Yorkshire, and briefly to Hay-on-Wye. And on the way back they collected Podey, whom he’d had stuffed. Harrison muses on the English “vice” of nostalgia for a past that probably never existed; Pugwash does what cats do, and very well.

They encountered Morris dancers, gypsies, hippies at Stonehenge for the Summer Solstice, sisters having a double wedding, and magic mushroom collectors. They went to a county fair and beaches in Suffolk and East Yorkshire, and briefly to Hay-on-Wye. And on the way back they collected Podey, whom he’d had stuffed. Harrison muses on the English “vice” of nostalgia for a past that probably never existed; Pugwash does what cats do, and very well. Belinda, on the other hand, only has eyes for one man: Archdeacon Hochleve, whom she’s known and loved for 30 years. They share a fondness for quoting poetry, the more obscure the better (like the title phrase, taken from “Some tame gazelle, or some gentle dove: / Something to love, oh, something to love!” by Thomas Haynes Bayly). The only problem is that the archdeacon is happily married. So single-minded is Belinda that she barely notices her own marriage proposal when it comes: a scene that reminded me of Mr. Collins’s proposal to Lizzie in Pride and Prejudice. Indeed, Pym is widely recognized as an heir to Jane Austen, what with her arch studies of relationships in a closed community.

Belinda, on the other hand, only has eyes for one man: Archdeacon Hochleve, whom she’s known and loved for 30 years. They share a fondness for quoting poetry, the more obscure the better (like the title phrase, taken from “Some tame gazelle, or some gentle dove: / Something to love, oh, something to love!” by Thomas Haynes Bayly). The only problem is that the archdeacon is happily married. So single-minded is Belinda that she barely notices her own marriage proposal when it comes: a scene that reminded me of Mr. Collins’s proposal to Lizzie in Pride and Prejudice. Indeed, Pym is widely recognized as an heir to Jane Austen, what with her arch studies of relationships in a closed community. This compact and fairly rollicking book is a natural history of butterflies and of the scientists and collectors who have made them their life’s work. There are some 18,000 species and, unlike, say, beetles, they are generally pretty easy to tell apart because of their bold, colorful markings. Moth and butterfly diversity may well be a synecdoche for overall diversity, making them invaluable indicator species. Although the history of butterfly collecting was fairly familiar to me from Peter Marren’s Rainbow Dust, I still learned or was reminded of a lot, such as the ways you can tell moths and butterflies apart (and it’s not just about whether they fly in the night or the day). And who knew that butterfly rape is a thing?

This compact and fairly rollicking book is a natural history of butterflies and of the scientists and collectors who have made them their life’s work. There are some 18,000 species and, unlike, say, beetles, they are generally pretty easy to tell apart because of their bold, colorful markings. Moth and butterfly diversity may well be a synecdoche for overall diversity, making them invaluable indicator species. Although the history of butterfly collecting was fairly familiar to me from Peter Marren’s Rainbow Dust, I still learned or was reminded of a lot, such as the ways you can tell moths and butterflies apart (and it’s not just about whether they fly in the night or the day). And who knew that butterfly rape is a thing? I also recently read the excellent title story from John Murray’s 2003 collection A Few Short Notes on Tropical Butterflies. Married surgeons reflect on their losses, including the narrator’s sister in a childhood accident and his wife Maya’s father to brain cancer. In the late 1800s, the narrator’s grandfather, an amateur naturalist in the same vein as Darwin, travelled to Papua New Guinea to collect butterflies. The legends from his time, and from family trips to Cape May to count monarchs on migration in the 1930s, still resonate in the present day for these characters. The treatment of themes like science, grief and family inheritance, and the interweaving of past and present, reminded me of work by Andrea Barrett and A.S. Byatt.

I also recently read the excellent title story from John Murray’s 2003 collection A Few Short Notes on Tropical Butterflies. Married surgeons reflect on their losses, including the narrator’s sister in a childhood accident and his wife Maya’s father to brain cancer. In the late 1800s, the narrator’s grandfather, an amateur naturalist in the same vein as Darwin, travelled to Papua New Guinea to collect butterflies. The legends from his time, and from family trips to Cape May to count monarchs on migration in the 1930s, still resonate in the present day for these characters. The treatment of themes like science, grief and family inheritance, and the interweaving of past and present, reminded me of work by Andrea Barrett and A.S. Byatt.