#1925Club: The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov

Simon and Kaggsy’s classics reading weeks always get me picking up older books. I found this unusual Russian novella on a giveaway pile a few years ago and it’s been on my #NovNov possibility shelf ever since, but now turned out to be the perfect time for it. This review also fits into the Hundred Years Hence challenge.

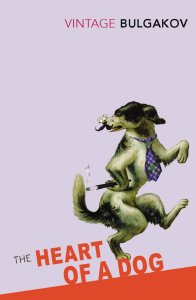

Sharik is an abused stray dog, living on scraps on the snowy streets of Moscow until Professor Philip Philipovich Preobrazhensky takes him in. The professor is a surgeon renowned for his rejuvenation procedures – implanting monkey ovaries into a middle-aged lady, for instance – and he has designs on the mutt. His new strategy is to take the pituitary gland and testicles of a just-deceased young man and transplant them into Sharik. The central chapter is composed of medical notes taken by Preobrazhensky’s assistant, Dr. Bormenthal. Gradually, a transformation is achieved: The dog’s bark becomes more of a human groan and his fur and tail fall off. Soon the new man is fully convincing: eating, dressing and conversing. Even in a matter-of-fact style, the doctor’s clinical observations are hilarious. “The dog[,] in the presence of Zina and myself, had called Prof. Preobrazhensky a ‘bloody bastard’. … Heard to ask for ‘another one, and make it a double.’” The scientists belatedly look into the history of the man whose glands they harvested and discover to their horror that he was an alcoholic petty thief who died in a bar fight. Sharikov follows suit as an inebriated boor who pesters women, wants to be known as Poligraph Poligraphovich – and still chases cats. Is it too late to reverse a Frankenstein-esque trial gone wrong?

This was a fairly entertaining fable-like story, with whimsical fragments of narration from Sharik himself at the start and close. The blurb inside the jacket of my 1968 Harvill Press hardback suggests “The Heart of a Dog can be enjoyed solely as a comic story of splendid absurdity; it can also be read as a fierce parable about the Russian Revolution.” The allegorical meaning could easily have passed me by, being less overt than in Animal Farm. Reading a tiny bit of external information, I see that this has been interpreted as a satire on the nouveau riche during the Bolshevik era: Sharikov complains about how wealthy the professor is and proposes that he sacrifice some of his apartment-cum-office’s many rooms to others who have nowhere to live. But yes, I mostly stayed at the surface level and found an amusing mad-scientist cautionary tale. I’ll read more by Bulgakov – I’ve had a copy of The Master and Margarita for ages. Next year’s Reading the Meow week might be my excuse.

This was a fairly entertaining fable-like story, with whimsical fragments of narration from Sharik himself at the start and close. The blurb inside the jacket of my 1968 Harvill Press hardback suggests “The Heart of a Dog can be enjoyed solely as a comic story of splendid absurdity; it can also be read as a fierce parable about the Russian Revolution.” The allegorical meaning could easily have passed me by, being less overt than in Animal Farm. Reading a tiny bit of external information, I see that this has been interpreted as a satire on the nouveau riche during the Bolshevik era: Sharikov complains about how wealthy the professor is and proposes that he sacrifice some of his apartment-cum-office’s many rooms to others who have nowhere to live. But yes, I mostly stayed at the surface level and found an amusing mad-scientist cautionary tale. I’ll read more by Bulgakov – I’ve had a copy of The Master and Margarita for ages. Next year’s Reading the Meow week might be my excuse.

[Translated from Russian by Michael Glenny, 1968]

(Free from a neighbour, formerly part of Scarborough Public Library stock) ![]()

I also intended to read An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser from the university library, having a dim memory of a black-and-white film version starring Montgomery Clift (A Place in the Sun). But the catalogue’s promised 400-some pages was a lie; there are two volumes in one, totaling 840 pages. So that was a nonstarter.

But here are some other famous 1925 titles that I’ve read (I’m now at 7 out of the top 15 on the Goodreads list of the most popular books published in 1925):

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Trial by Franz Kafka

The Painted Veil by W. Somerset Maugham

Emily Climbs by L.M. Montgomery

Carry On, Jeeves by P.G. Wodehouse

Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, 1940 Club, 1937 Club, 1970 Club, and 1952 Club.

Classic of the Month: Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev

Last month’s classic was Father and Son (Edmund Gosse); this month is Fathers and Sons, the 1861 novel by Ivan Turgenev (1818–83). I couldn’t resist pairing up the similar titles, and it turns out that even though one is nonfiction and the other fiction, they are thematically similar, dwelling on the clash of generations and contrasting romanticism and rationalism.

Nikolai Kirsanov’s son Arkady, newly graduated from university, has just returned to his father’s estate with his haughty fellow student Yevgeny Bazarov in tow. Bazarov intends to take a medical degree and follow in his father’s footsteps as a country doctor, so spends the time at his friend’s house dutifully poring over chemistry texts and dissecting frogs. Arkady, by contrast, seems earnest but aimless, happy to simply while away the days. The major change at home is that his father, a widower, has taken the servant girl Fenichka as his mistress and they have a baby, Mitya. (Gasp!) Yet the real shock in the world of the novel seems to be that Nikolai is consorting with someone of the lower classes. “In any case, it’s not for a son to sit in judgment on his father – least of all for me, and least of all with a father like you, who has never restricted my freedom in any way,” Arkady graciously concedes.

Nikolai Kirsanov’s son Arkady, newly graduated from university, has just returned to his father’s estate with his haughty fellow student Yevgeny Bazarov in tow. Bazarov intends to take a medical degree and follow in his father’s footsteps as a country doctor, so spends the time at his friend’s house dutifully poring over chemistry texts and dissecting frogs. Arkady, by contrast, seems earnest but aimless, happy to simply while away the days. The major change at home is that his father, a widower, has taken the servant girl Fenichka as his mistress and they have a baby, Mitya. (Gasp!) Yet the real shock in the world of the novel seems to be that Nikolai is consorting with someone of the lower classes. “In any case, it’s not for a son to sit in judgment on his father – least of all for me, and least of all with a father like you, who has never restricted my freedom in any way,” Arkady graciously concedes.

Together Nikolai and his rakish brother Pavel (“Women lost their heads over him, and men dubbed him a fop but were secretly envious”) represent an outmoded idealism that values art, nature, poetry, and true love. On the other side is Bazarov, who means to tear down those dated notions and recruit Arkady to the side of realism, even nihilism. “Nature is not a temple, but a workshop, and man’s the workman in it,” he explains to Arkady. But the pals’ notions get uncomfortably muddled when they meet the regal widow Anna Odintsov at the governor’s ball. On extended visits to her country house, Bazarov and Arkady become fixated on her and her younger sister, Katya, but differ in their willingness to give in to love.

Romantic love may be a madness best avoided in some of the characters’ view, but family love is a constant. Even Bazarov, though he makes a show of being embarrassed by their fussing when he goes home briefly after three years away, values his parents’ approval. His father proudly takes him along on his medical rounds, while his superstitious mother buttresses him with her prayers. She reminds her husband that Yevgeny is fundamentally different from them: “A son is an independent person. He’s like a falcon that comes when he wills and flies off when he lists; but you and I are like the funguses growing in a hollow tree.”

I was pleasantly surprised by how enjoyable and accessible Turgenev’s writing is. My experience with the Russian masters is shamefully limited; Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich might literally be the only thing I’ve read previously. I was worried that all the patronymics, place names, and historical and cultural references would trip me up, but it’s no trouble to adjust to them here. You might think of Fathers and Sons as a friendly way of easing in to works like War and Peace: although elements of the story reminded me of Tolstoy’s epic (as I know it purely from the recent BBC miniseries) – the range of characters, from rich to poor, and their interactions; the long visits to acquaintances; the peaceful countryside; even a duel – it is on a much smaller scale, and has a correspondingly lower page count of about 220.

Something in nearly every character’s psyche rang true for me: Arkady’s relief at being home; Nikolai’s sense of being left behind; Bazarov’s feeling of smallness in an uncaring universe; his mother’s benevolent contentment with the status quo; Madame Odintsov’s well-ordered but purposeless life; and so on. Turgenev’s asides about Russia and about human nature give the narration a playful, knowing quality reminiscent of George Eliot. The idea of fathers and children being on different tracks extends to other forms of paternalism: religion (though this is a minor theme compared to in Father and Son) as well as masters versus serfs. “We all know there’s the master’s will; on account of you bein’ like our fathers. An’ the more strict the master rules, the better it be for us peasants,” as one rustic opines to Bazarov.

This is a thought-provoking but markedly readable classic that I can heartily recommend. Turgenev only wrote five other novels; if they’re all as strong (and roughly as short) as this one, I’d be happy to read them all – and will likely return to Fathers and Sons in the future.

My rating:

(With thanks to Karen at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings for putting Turgenev on my radar.)

I read a Penguin Classics edition of Rosemary Edmonds’s 1965 translation. Her brief introduction gives helpful background and is a lovely piece of writing in its own right. Beware: only read a literary introduction after finishing the text, because critics assume you know the basic story line and so spoil who falls in love with whom, who dies in the end, etc. My edition is preceded by a lengthy lecture Isaiah Berlin gave on Turgenev in 1970.

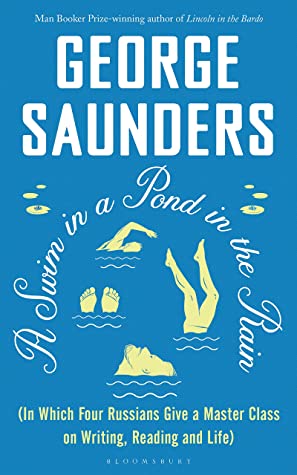

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

Ishiguro’s new novel, Klara and the Sun, was published by Faber yesterday. This conversation with Alex Clark also functioned as its launch event. It’s one of

Ishiguro’s new novel, Klara and the Sun, was published by Faber yesterday. This conversation with Alex Clark also functioned as its launch event. It’s one of