The Single Hound by May Sarton (1938)

I spotted that the 30th anniversary of May Sarton’s death was coming up, so decided to read an unread book of hers from my shelves in time to mark the occasion. Today’s the day: she died on July 16, 1995 in York, Maine. Marcie of Buried in Print joined me for a buddy read (her review). I was drawn by the title, which comes from an Emily Dickinson quote. It’s the ninth Sarton novel I’ve read and, while in general I find her nonfiction more memorable than her fiction, this impressionistic debut novel was a solid read. It was clearly inspired by Virginia Woolf’s work and based on Sarton’s memories of her time on the fringes of the Bloomsbury Group.

In Part I we are introduced to “the Little Owls,” three dear friends and winsome spinsters in their sixties – Doro, Annette and Claire – who teach and live above their schoolroom in Ghent, Belgium. (I couldn’t help but think of the Brontë sisters’ time in Belgium.) Doro, a poet, seems likely to be a stand-in for the author. I loved the gentle pace of this section; although the novel was published when she was only 26, Sarton was already displaying insight into friendship and ageing and appreciation of life’s small pleasures, elements that would recur in her later autobiographical work.

In Part I we are introduced to “the Little Owls,” three dear friends and winsome spinsters in their sixties – Doro, Annette and Claire – who teach and live above their schoolroom in Ghent, Belgium. (I couldn’t help but think of the Brontë sisters’ time in Belgium.) Doro, a poet, seems likely to be a stand-in for the author. I loved the gentle pace of this section; although the novel was published when she was only 26, Sarton was already displaying insight into friendship and ageing and appreciation of life’s small pleasures, elements that would recur in her later autobiographical work.

the three together made a complete world.

Was this life? This slow penetration of experience until nothing had been left untasted, unexplored, unused — until the whole of one’s life became a fabric, a tapestry with a pattern? She could not see the pattern yet.

tea was opium to them both, the time when the past became a soft pleasant country of the imagination, lost its bitterness, ceased to devour, and in some tea-inspired way nourished them.

Part II felt to me like a strange swerve into the story of Mark Taylor, an aspiring English writer who falls in love with a married painter named Georgia Manning. Their flirtation, as soon through the eyes of a young romantic like Mark, is monolithic, earth-shattering, but to readers is more of a clichéd subplot. In the meantime, Mark sticks to his vow of going on a pilgrimage to Belgium to meet Jean Latour, the poet whose work first inspired him. Part III brings the two strands together in an unexpected way, as Mark gains clarity about his hero and his potential future with Georgia, though cleverer readers than I may have been able to predict it – especially if they heeded the Brontë connection.

It was rewarding to spot the seeds of future Sarton themes here, such as discovering the vocation of teaching (The Small Room) and young people meeting their elder role models and soliciting words of wisdom on how to live (Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing). Through Doro, Sarton also expresses trust in poetry’s serendipitous power. “This is why one is a poet, so that some day, sooner or later, one can say the right thing to the right person at the right time.” I enjoyed my time with the Little Owls but mostly viewed this as a dress rehearsal for later, more mature work. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

Reviewing Two Books by Cancelled Authors

I don’t have anything especially insightful to say about these authors’ reasons for being cancelled, although in my review of the Clanchy I’ve noted the textual examples that have been cited as problematic. Alexie is among the legion of male public figures to have been accused of sexual misconduct in recent years. I’m not saying those aren’t serious allegations, but as Claire Dederer wrestled with in Monsters, our judgement of a person can be separate from our response to their work. So that’s the good news: I thought these were both fantastic books. They share a theme of education.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (illus. Ellen Forney) (2007)

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

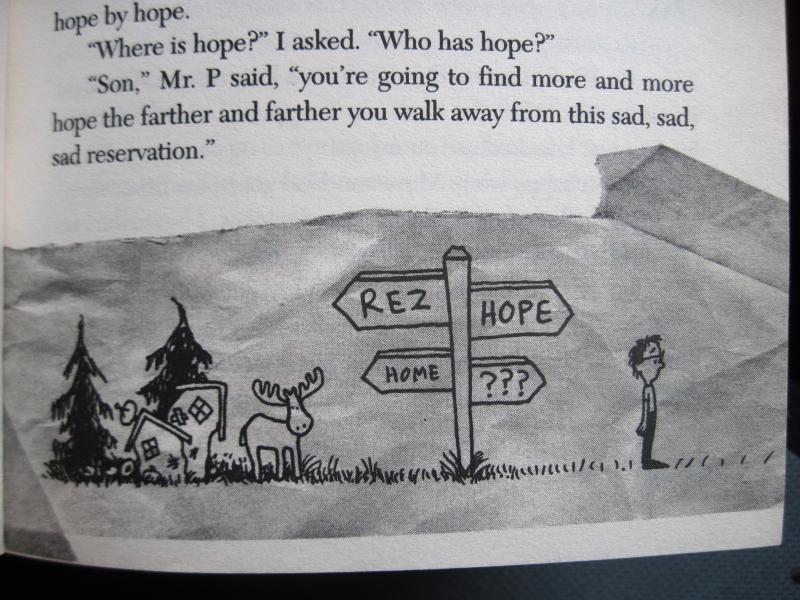

It reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable; Alexie’s tone is spot on. Junior has had a tough life on a Spokane reservation in Washington, being bullied for his poor eyesight and speech impediments that resulted from brain damage at birth and ongoing seizures. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations here because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior’s parents never got to pursue their dreams and his sister has run away to Montana, but he has a chance to change the trajectory. A rez teacher says his only hope for a bright future is to transfer to the elite high school in Reardan. So he does, even though it often requires hitch-hiking or walking miles.

Junior soon becomes adept at code-switching: “Traveling between Reardan and Wellpinit, between the little white town and the reservation, I always felt like a stranger. I was half Indian in one place and half white in the other.” He gets a white girlfriend, Penelope, but has to work hard to conceal how impoverished he is. His best friend, Rowdy, is furious with him for abandoning his people. That resentment builds all the way to a climactic basketball match between Reardan and Wellpinit that also functions as a symbolic battle between the parts of Junior’s identity. Along the way, there are multiple tragic deaths in which alcohol, inevitably, plays a role. “I’m fourteen years old and I’ve been to forty-two funerals,” he confides. “Jeez, what a sucky life. … I kept trying to find the little pieces of joy in my life. That’s the only way I managed to make it through all of that death and change.”

One of those joys, for him, is cartooning. Describing his cartoons to his new white friend, Gordy, he says, “I use them to understand the world.”

Forney’s black-and-white illustrations make the cartoons look like found objects – creased scraps of notebook paper sellotaped into a diary. This isn’t a graphic novel, but most of the short chapters include several illustrations. There’s a casual intimacy to the whole book that feels absolutely authentic. Bridging the particular and universal, it’s a heartfelt gem, and not just for teens. (University library) ![]()

Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy (2019)

If your Twitter sphere and mine overlap, you may remember the controversy over the racialized descriptions in this Orwell Prize-winning memoir of 30 years of teaching – and the fact that, rather than issuing a humbled apology, Clanchy, at least initially, doubled down and refuted all objections, even when they came from BIPOC. It wasn’t a good look. Nor was it the first time I’ve found Clanchy to be prickly. (She is what, in another time, might have been called a formidable woman.) Anyway, I waited a few years for the furore to die down before trying this for myself.

I know vanishingly little about the British education system because I don’t have children and only experienced uni here at a distance, through my junior year abroad. So there may be class-based nuances I missed – for instance, in the chapter about selecting a school for her oldest son and comparing it with the underprivileged Essex school where she taught. But it’s clear that a lot of her students posed serious challenges. Many were refugees or immigrants, and she worked for a time on an “Inclusion Unit,” which seems to be more in the business of exclusion in that it’s for students who have been removed from regular classrooms. They came from bad family situations and were more likely to end up in prison or pregnant. To get any of them to connect with Shakespeare, or write their own poetry, was a minor miracle.

Clanchy is also a poet and novelist – I’ve read one of her novels, and her Selected Poems – and did much to encourage her students to develop a voice and the confidence to have their work published (she’s produced anthologies of student work). In many cases, she gave them strategies for giving literary shape to traumatic memories. The book’s engaging vignettes have all had the identifying details removed, and are collected under thematic headings that address the second part of the title: “About Love, Sex, and the Limits of Embarrassment” and “About Nations, Papers, and Where We Belong” are two example chapters. She doesn’t avoid contentious topics, either: the hijab, religion, mental illness and so on.

You get the feeling that she was a friend and mentor to her students, not just their teacher, and that they could talk to her about anything and rely on her support. Watching them grow in self-expression is heart-warming; we come to care for these young people, too, because of how sincerely they have been created from amalgams. Indeed, Clanchy writes in the introduction that “I have included nobody, teacher or pupil, about whom I could not write with love.”

And that is, I think, why she was so hurt and disbelieving when people pointed out racism in her characterization:

I was baffled when a boy with jet-black hair and eyes and a fine Ashkenazi nose named David Marks refused any Jewish heritage

her furry eyebrows, her slanting, sparking black eyes, her general, Mongolian ferocity. [but she’s Afghan??]

(of girls in hijabs) I never saw their (Asian/silky/curly?) hair in eight years.

They’re a funny pair: Izzat so small and square and Afghan with his big nose and premature moustache; Mo so rounded and mellow and Pakistani with his long-lashed eyes and soft glossy hair.

There are a few other ill-advised passages. She admits she can’t tell the difference between Kenyan and Somali faces; she ponders whether being a Scot in England gave her some taste of the prejudice refugees experience. And there’s this passage about sexuality:

Are we all ‘fluid’ now? Perhaps. It is commonplace to proclaim oneself transsexual. And to actually be gay, especially if you are as pretty as Kristen Stewart, is positively fashionable. A couple of kids have even changed gender, a decision … deliciously of the moment

My take: Clanchy wanted to craft affectionate pen portraits that celebrated children’s uniqueness, but had to make them anonymous, so resorted to generalizations. Doing this on a country or ethnicity basis was the mistake. Journalistic realism doesn’t require a focus on appearances (I would hope that, if I were ever profiled, someone could find more interesting things to say about me than that I am short and have a large nose). She could have just introduced the students with ‘facts,’ e.g., “Shakila, from Afghanistan, wore a hijab and was feisty and outspoken.” Note to self: white people can be clueless, and we need to listen and learn. The book was reissued in 2022 by independent publisher Swift Press, with offending passages removed (see here for more info). I’d be keen to see the result and hope that the book will find more readers because, truly, it is lovely. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Someone becomes addicted to benzodiazepines in The Pass by Katriona Chapman and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun (both 2026 releases).

Someone becomes addicted to benzodiazepines in The Pass by Katriona Chapman and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun (both 2026 releases).

A sexual encounter between two men is presaged by them relieving themselves side by side at urinals in A Room Above a Shop by Anthony Shapland and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.

A sexual encounter between two men is presaged by them relieving themselves side by side at urinals in A Room Above a Shop by Anthony Shapland and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.