Spring Journeys with Edwin Way Teale and Edward Thomas

When I heard that Little Toller were reissuing their edition of Edward Thomas’s In Pursuit of Spring, I couldn’t resist pairing it with Edwin Way Teale’s book about the progress of the season up the United States, North with the Spring. These spring journeys, documented by authors delighting in nature’s bounty and responding with poetry, inspired mixed feelings in me: vicarious nostalgia, but also sadness for all that has been lost since they set out in the 1910s and 1950s, respectively.

It’s hard to live joyfully when evidence of the destruction of nature is overwhelming. Enjoying what still exists doesn’t seem like enough. But it’s a start. So this year I’ve been careful to note every phenological landmark: the first swift, the first hearing of a cuckoo, a rare sighting of a live hedgehog. One day in late April I stood on the towpath for hours watching a cloud of swallows and martins swooping for insects. I’ve also enjoyed watching from my office window as sparrows come and go from a nest box.

North with the Spring by Edwin Way Teale (1951)

I’ve previously reviewed Teale’s Autumn Across America and Springtime in Britain and consider him one of the classic – and most underrated – American nature writers. I was delighted to find a copy of this first seasonal volume on our trip to Northumberland a few years ago. As in the autumn book, he and his wife Nellie undertake a road trip, this time travelling from Florida up to New England, a total of 17,000 miles. Their journey lasted 130 days because instead of waiting for 21 March they started weeks before; spring comes early to the Gulf coast. Their time in Florida feels endless, constituting over a third of the book. Although it’s true that there are (were?) many peerless ecosystems there between the scrub and swamp, I grew impatient to move on to other states. The meet-up with Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, who took them on a picnic to ‘The Yearling country,’ was a highlight.

They travel alongside the spring warblers; past river deltas and barrier islands, by mountain meadows and forests. Other stops include Monticello and New Jersey’s pine barrens. A stopover in New York City dramatizes the difference between civilization and relative wilderness. I particularly enjoyed a pair of chapters set in Tennessee: first the wonder of Nickajack Cave, then the horror of the deforested and poisoned Ducktown Desert. Teale seems ahead of his time in decrying people’s wilful ignorance – one man they met denied the fact of migration, insisting the birds were always around – and failure to consider nature. His scenes and conversations feel fully natural; he’s as interested in people as in wildlife, and that humanism comes across in his writing.

They travel alongside the spring warblers; past river deltas and barrier islands, by mountain meadows and forests. Other stops include Monticello and New Jersey’s pine barrens. A stopover in New York City dramatizes the difference between civilization and relative wilderness. I particularly enjoyed a pair of chapters set in Tennessee: first the wonder of Nickajack Cave, then the horror of the deforested and poisoned Ducktown Desert. Teale seems ahead of his time in decrying people’s wilful ignorance – one man they met denied the fact of migration, insisting the birds were always around – and failure to consider nature. His scenes and conversations feel fully natural; he’s as interested in people as in wildlife, and that humanism comes across in his writing.

“We longed for a thousand springs on the road instead of this one. For spring is like life. You never grasp it entire; you touch it here, there; you know it only in parts and fragments.”

(Secondhand – Barter Books, Alnwick)

In Pursuit of Spring by Edward Thomas (1914)

On Good Friday, 21 March 1913, Edward Thomas set off on his bicycle from his parents’ home in South London. He was bound southwest, toward Somerset and the height of spring. At cycling and walking pace, he would truly experience the development of the season, whereas

“Many days in London have no weather. We are aware only that it is hot or cold, dry or wet; that we are in or out of doors; that we are at ease or not.”

He prepares himself for hardship and slog:

“Spring would come, of course – nothing, I supposed, could prevent it – and I should have to make up my mind how to go westward. Whatever I did, Salisbury Plain was to be crossed”

It’s remarkable both how much and how little has changed in the intervening century and more. The place names, plant and bird species, and alternation of town and countryside are all familiar, but the difference is stark when you see Thomas’s black-and-white photographs that illustrate the text. These dirt roads are empty. You’d have to search high and low today to find the kind of unspoiled fields, rivers, churchyards, hedgerows and stone walls that he memorializes.

It’s remarkable both how much and how little has changed in the intervening century and more. The place names, plant and bird species, and alternation of town and countryside are all familiar, but the difference is stark when you see Thomas’s black-and-white photographs that illustrate the text. These dirt roads are empty. You’d have to search high and low today to find the kind of unspoiled fields, rivers, churchyards, hedgerows and stone walls that he memorializes.

Everything he sees drives him back to poetry, with long passages quoted from authors who have fallen somewhat out of fashion, such as George Herbert and Alexander Pope. I loved the scene where he buys a book at a secondhand furniture shop (for two pence, mind you) and then ignores it to eavesdrop on fellow diners at a restaurant. He has words of high praise for W.H. Hudson:

“Were men to disappear they might be reconstructed from the Bible and the Russian novelists; … Hudson so writes of birds that if ever … they should cease to exist, and should leave us to ourselves on a benighted planet, we should have to learn from him what birds were.”

Thomas also mentions William Cobbett, whose Rural Rides this reminded me of strongly. Both are slow-paced journeys around a rural England that no longer exists. Today Thomas is better remembered as a poet; he would be one of the fallen in a First World War battle just four years after this expedition. It was great to have a chance to read his nature writing, too.

With thanks to Little Toller for the free copy for review.

We’re off to rural France on Wednesday for eight days of relaxation and nature-watching; it’s not a sight-seeing or foodie trip like our time in Paris back in December. Ironically, it seems that it may be cold and rainy for much of the holiday, having been gorgeous in both countries this past week. We will hope for some sun and warmth, but have packed plenty of books and board games (and will acquire much wine) for when the weather is to be avoided inside.

What signs of the spring have you been seeing?

20 Books of Summer, #16–17, GREEN: Jon Dunn and W.H. Hudson

Today’s entries in my colour-themed summer reading are a travelogue tracking the world’s endangered hummingbirds and a bizarre classic novel that blends nature writing and fantasy. Though very different books, they have in common lush South American forest settings.

The Glitter in the Green: In Search of Hummingbirds by Jon Dunn (2021)

As a wildlife writer and photographer, Jon Dunn has come to focus on small and secretive but indelible wonders. His previous book, which I still need to catch up on, was all about orchids, and in this new one he travels the length of the Americas, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, to see as many hummingbirds as he can. He provides a thorough survey of the history, science and cultural relevance (from a mini handgun to an indie pop band) of this most jewel-like of bird families. The ruby-throated hummingbirds I grew up seeing in suburban Maryland are gorgeous enough, but from there the names and corresponding colourful markings just get more magnificent: Glittering-throated Emeralds, Tourmaline Sunangels, Violet-capped woodnymphs, and so on. I’ll have to get a look at the photos in a finished copy of the book!

Dunn is equally good at describing birds and their habitats and at constructing a charming travelogue out of his sometimes fraught journeys. He has only a narrow weather of fog-free weather to get from Chile to Isla Robinson Crusoe and the plane has to turn back once before it successfully lands; a planned excursion in Bolivia is a non-starter after political protestors block some main routes. There are moments when the thrill of the chase is rewarded – as when he sees 24 hummingbird species in a day in Costa Rica – and many instances of lavish hospitality from locals who serve as guides or open their gardens to birdwatchers.

Dunn is equally good at describing birds and their habitats and at constructing a charming travelogue out of his sometimes fraught journeys. He has only a narrow weather of fog-free weather to get from Chile to Isla Robinson Crusoe and the plane has to turn back once before it successfully lands; a planned excursion in Bolivia is a non-starter after political protestors block some main routes. There are moments when the thrill of the chase is rewarded – as when he sees 24 hummingbird species in a day in Costa Rica – and many instances of lavish hospitality from locals who serve as guides or open their gardens to birdwatchers.

Like so many creatures, hummingbirds are in dire straits due to human activity: deforestation, invasive species, pesticide use and climate change are reducing the areas where they can live to pockets here and there; some species number in the hundreds and are considered critically endangered. Dunn juxtaposes the exploitative practices of (white, male) 19th- and 20th-century bird artists, collectors and hunters with indigenous birdwatching and environmental initiatives that are rising up to combat ecological damage in Latin America. Although society has moved past the use of hummingbird feathers in crafts and fashion, he learns that the troubling practice of dead hummingbirds being sold as love charms (chuparosas) persists in Mexico.

Whether you’re familiar with hummingbirds or not, if you have even a passing interest in nature and travel writing, I recommend The Glitter in the Green for how it invites readers into a personal passion, recreates an adventurous odyssey, and reinforces our collective responsibility for threatened wildlife. (Proof copy passed on by Paul of Halfman, Halfbook)

A lovely folk tale I’ll quote in full:

A hummingbird as a symbol of hope, strength and endurance is a recurrent one in South American folklore. An Ecuadorian folk tale tells of a forest on fire – a hummingbird picks up single droplets of water in its beak and lets them fall on the fire. The other animals in the forest laugh, and ask the hummingbird what difference this can possibly make. They say, ‘Don’t bother, it is too much, you are too little, your wings will burn, your beak is too tiny, it’s only a drop, you can’t put out this fire. What do you think you are doing?’ To which the hummingbird is said to reply, ‘I’m just doing what I can.’

Links between the books: Hudson is quoted in Dunn’s introduction. In Chapter 7 of the below, Hudson describes a hummingbird as “a living prismatic gem that changes its colour with every change of position … it catches the sunshine on its burnished neck and gorget plumes—green and gold and flame-coloured, the beams changing to visible flakes as they fall”

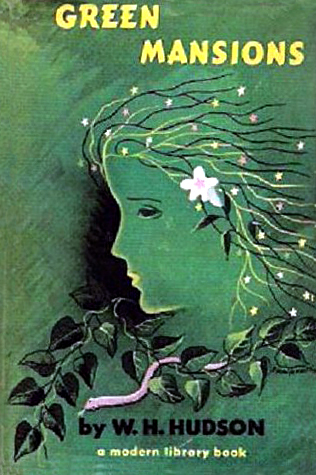

Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest by W.H. Hudson (1904)

Like Heart of Darkness, this is a long recounted tale about a journey among ‘savages’. After a prologue, the narrator soon cedes storytelling duties to Mr. Abel, whom he met in Georgetown, Guyana in 1887. Searching for gold and fighting off illness, the 23-year-old Abel took up the habit of wandering the Venezuelan forest. The indigenous people were superstitious and refused to hunt in that forest. Abel began to hear strange noises – magical bird calls or laughter – that, siren-like, drew him deeper in. His native friend warned him it was the daughter of an evil spirit.

Like Heart of Darkness, this is a long recounted tale about a journey among ‘savages’. After a prologue, the narrator soon cedes storytelling duties to Mr. Abel, whom he met in Georgetown, Guyana in 1887. Searching for gold and fighting off illness, the 23-year-old Abel took up the habit of wandering the Venezuelan forest. The indigenous people were superstitious and refused to hunt in that forest. Abel began to hear strange noises – magical bird calls or laughter – that, siren-like, drew him deeper in. His native friend warned him it was the daughter of an evil spirit.

One day, after being bitten by a snake, Abel woke up in the dwelling of an old man and his 17-year-old granddaughter, Rima – the very wood sprite he’d sensed all these times in the forest; she saved his life. Recovering in their home and helping Rima investigate her origins, he romanticizes this tree spirit in a way that struck me as smarmy. It’s possible this could be appreciated as a fable of connection with nature, but I found it vague and old-fashioned. (Not to mention Abel’s condescending attitude to the indigenous people and to women.) I ended up skimming the last three-quarters.

My husband has read nonfiction by Hudson; I think I was under the impression that this was a memoir, in fact. Perhaps I’d enjoy Hudson’s writing in another genre. But I was surprised to read high praise from John Galsworthy in the foreword (“For of all living authors—now that Tolstoi has gone—I could least dispense with W. H. Hudson”) and to note how many of my Goodreads friends have read this; I don’t see it as a classic that stands the test of time.

My 1944 hardback once belonged to one Mary Marcilliat of Louisville, Kentucky, and has strange abstract illustrations by E. McKnight Kauffer. (Free from the Book Thing of Baltimore)

Coming up next: One black and one gold on Wednesday; a Green author and a rainbow bonus (probably on the very last day).

Would you be interested in reading one of these?

More Seasonal Reading

I like this reading with the seasons lark. It’s a shame that my library hold on Ali Smith’s Autumn didn’t come in until well after it turned to winter here in England, but I was intrigued by the sound of her post-Brexit seasonal quartet. Then, as if one winter anthology wasn’t enough, I tried another – this time a broader range of literature, history and travel writing.

Autumn by Ali Smith

Smith is attempting a sort of state-of-the-nation novel in four parts. Her two main characters are Daniel Gluck, a centenarian dying at a care home, and his former next-door neighbor, Elisabeth Demand, in her early thirties and still figuring out her path in life. The present world Elisabeth and her mother navigate is a true-to-life post-Brexit bureaucratic nightmare where people are building walls and hurling racist epithets – “news right now is like a flock of speeded-up sheep running off the side of a cliff.” Mostly the book is composed of flashbacks to wordplay-filled conversations between Elisabeth and Daniel when he used to babysit for her, as well as dreams/hallucinations Daniel is having on his deathbed. But there’s also a lot of seemingly irrelevant material about pop artist Pauline Boty and Christine Keeler.

Smith is attempting a sort of state-of-the-nation novel in four parts. Her two main characters are Daniel Gluck, a centenarian dying at a care home, and his former next-door neighbor, Elisabeth Demand, in her early thirties and still figuring out her path in life. The present world Elisabeth and her mother navigate is a true-to-life post-Brexit bureaucratic nightmare where people are building walls and hurling racist epithets – “news right now is like a flock of speeded-up sheep running off the side of a cliff.” Mostly the book is composed of flashbacks to wordplay-filled conversations between Elisabeth and Daniel when he used to babysit for her, as well as dreams/hallucinations Daniel is having on his deathbed. But there’s also a lot of seemingly irrelevant material about pop artist Pauline Boty and Christine Keeler.

This was most likely written very quickly in response to current events, and while some of Smith’s strengths benefit from immediacy – the nearly stream-of-consciousness style (no speech marks) and the jokey dialogue – I think I would have preferred a more circumspect, compressed narrative. In places this was too repetitive, and the seasonal theme felt neither here nor there. I’ll listen out for what the other books are like, but doubt I’ll bother reading them. Aspects of this are very similar to Number 11 by Jonathan Coe (the state-of-Britain remit, even the single mother hoping to appear on a reality show), but I much preferred his take. [Gorgeous cover, though – David Hockney’s Early November Tunnel (2006).]

My rating:

[For more positive reviews, see those by Eric of Lonesome Reader, and Lucy of Hard Book Habit.]

Winter: A Book for the Season, edited by Felicity Trotman

This seasonal anthology contains a nice mixture of poetry, nature and travel pieces, and excerpts from longer works of fiction. Some favorite pieces were W.H. Hudson on the town birds of Bath in the late nineteenth century, Mark Twain on his determination to keep wearing his trademark white through the winter, a Hans Christian Andersen dialogue between a snowman who longs to be by the stove and the yard-dog that warns him away, and Richard Jefferies on those who go out to work on a winter morning. But I enjoyed the poetry the most. Trotman includes a wide range of celebrated poets, from Shakespeare and Keats to John Clare and Wordsworth. I particularly liked a more recent contribution from Carolyn King, “First Snow,” in which a cat imagines that a giant wallpaper stripper has produced the flakes.

This seasonal anthology contains a nice mixture of poetry, nature and travel pieces, and excerpts from longer works of fiction. Some favorite pieces were W.H. Hudson on the town birds of Bath in the late nineteenth century, Mark Twain on his determination to keep wearing his trademark white through the winter, a Hans Christian Andersen dialogue between a snowman who longs to be by the stove and the yard-dog that warns him away, and Richard Jefferies on those who go out to work on a winter morning. But I enjoyed the poetry the most. Trotman includes a wide range of celebrated poets, from Shakespeare and Keats to John Clare and Wordsworth. I particularly liked a more recent contribution from Carolyn King, “First Snow,” in which a cat imagines that a giant wallpaper stripper has produced the flakes.

All told, though, there are too many seventeenth-century and older pieces with archaic spellings, and a number of the history and travel extracts, in particular, feel overlong – with nearly 40 pages in total from Ernest Shackleton’s South. Especially given the thin pages and small type, this represents a tediously large chunk of the book. Shorter pieces increase the variety in an anthology and mean the book lends itself to being picked up and read a few stories at a time. This is one to keep on the coffee table each winter and dip into over several years rather than read straight through. (See my full review at The Bookbag.)

My rating:

As it happens, I’ve now read five books titled Winter: besides the Wildlife Trusts anthology and the novel about Thomas Hardy, both of which I’ve already reviewed here, there’s also Rick Bass’s wonderful memoir of his first year in Montana and Adam Gopnik’s wide-ranging book about the season. But beyond those with the simple one-word title, there are a whole host of titles on my TBR containing the word “Winter”. Here’s the whole list!

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom.

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom. A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

The format in all the books is roughly the same: they’re composed of short pieces that range from one to a few pages and run the gamut from recurring phenological records (Gilbert White and Thomas Furly Forster) and extracts from classic literature (Adam Bede and Far from the Madding Crowd) to recent nature books (Mark Cocker’s

The format in all the books is roughly the same: they’re composed of short pieces that range from one to a few pages and run the gamut from recurring phenological records (Gilbert White and Thomas Furly Forster) and extracts from classic literature (Adam Bede and Far from the Madding Crowd) to recent nature books (Mark Cocker’s