Summery Classics by J. L. Carr and L. P. Hartley

“Do you remember what that summer was like? – how much more beautiful than any since?”

These two slightly under-the-radar classics made for perfect heatwave reading over the past couple of weeks: very English and very much of the historical periods that they evoke, they are nostalgic works remembering one summer when everything changed – or could have.

A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr (1980)

Summer 1920, North Yorkshire. Tom Birkin, a First World War veteran whose wife has left him, arrives in Oxgodby to uncover the local church’s wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long since whitewashed over. With nothing waiting for him back in London and no plans beyond this commission, he gives himself over to the daily rhythms of working, eating and sleeping – “There was so much time that marvelous summer.” This simple life is punctuated by occasional incidents like a Sunday school hayride and picnic, and filling in as a lay preacher at a nearby chapel. Also embarked on a quest into the past is Charles Moon, who is searching for the grave of their patroness’ ancestor in the churchyard. Moon, too, has a war history he’d rather forget.

Summer 1920, North Yorkshire. Tom Birkin, a First World War veteran whose wife has left him, arrives in Oxgodby to uncover the local church’s wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long since whitewashed over. With nothing waiting for him back in London and no plans beyond this commission, he gives himself over to the daily rhythms of working, eating and sleeping – “There was so much time that marvelous summer.” This simple life is punctuated by occasional incidents like a Sunday school hayride and picnic, and filling in as a lay preacher at a nearby chapel. Also embarked on a quest into the past is Charles Moon, who is searching for the grave of their patroness’ ancestor in the churchyard. Moon, too, has a war history he’d rather forget.

Though it barely exceeds 100 pages, this novella is full of surprises – about Moon, about the presumed identity and fate of the centuries-dead figures he and Birkin come to be obsessed with, and about the emotional connection that builds between Birkin and Reverend Keach’s wife, Alice. “It is now or never; we must snatch at happiness as it flies,” Birkin declares, but did he take his own advice? There is something achingly gorgeous about this not-quite-love story, as evanescent as ideal summer days. Carr writes in a foreword that he intended to write “a rural idyll along the lines of Thomas Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree.” He indeed created something Hardyesque with this tragicomic rustic romance; I was also reminded of another very English classic I reviewed earlier in the year: Cider with Rosie by Laurie Lee.

Source: Free bookshop

My rating:

A contemporary readalike: The Offing by Benjamin Myers

The Go-Between by L. P. Hartley (1953)

Summer 1900, Norfolk. Twelve-year-old Leo Colston is invited to spend the several July weeks leading up to his birthday at his school friend Marcus Maudsley’s home, Brandham Hall. Although the fatherless boy is keenly aware of the class difference between their families, in a year of learning to evade bullies he’s developed some confidence in his skills and pluck, fancying himself an amateur magician and gifted singer. Being useful makes him feel less like a charity case, so he eagerly agrees to act as “postman” for Marcus’s older sister, Marian, who exchanges frequent letters with their tenant farmer, Ted Burgess. Marian, engaged to Hugh, a viscount and injured Boer War veteran, insists the correspondence is purely business-related, but Leo suspects he’s abetting trysts the family would disapprove of.

Leo is right on the cusp of adolescence, a moment of transition that mirrors the crossing into a new century. As he glories in the summer’s mounting heat, “a liberating power with its own laws,” and mentally goads the weather into hitting ever greater extremes, he pushes against the limits of his innocence, begging Ted to tell him about “spooning” (that is, the facts of life). The heat becomes a character in its own right, gloweringly presiding over the emotional tension caused by secrets, spells and betrayals. And yet this is also a very funny novel: I loved Leo’s Franglais conversations with Marcus, and the confusion over mispronouncing “Hugh” as “you.” In places the tone even reminded me of Cold Comfort Farm.

Leo is right on the cusp of adolescence, a moment of transition that mirrors the crossing into a new century. As he glories in the summer’s mounting heat, “a liberating power with its own laws,” and mentally goads the weather into hitting ever greater extremes, he pushes against the limits of his innocence, begging Ted to tell him about “spooning” (that is, the facts of life). The heat becomes a character in its own right, gloweringly presiding over the emotional tension caused by secrets, spells and betrayals. And yet this is also a very funny novel: I loved Leo’s Franglais conversations with Marcus, and the confusion over mispronouncing “Hugh” as “you.” In places the tone even reminded me of Cold Comfort Farm.

Like A Month in the Country, this autobiographical story is an old man’s reminiscences, going back half a century in memory – but here Leo gets the chance to go back in person as well, seeing what has become of Brandham Hall and meeting one of the major players from that summer drama that branded him for life. I thought this masterfully done in every way: the class divide, the picture of childhood tipping over into the teenage years, the oppressive atmosphere, the comical touches. You know from the famous first line onwards (“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there”) that this will juxtapose past and present – which, of course, has now become past and further past – in a powerful way, similar to Moon Tiger, my favorite fiction read of last year. I’ll be exploring more of Hartley’s work.

(Note: Although I am a firm advocate of DNFing if a book is not working for you, I would also like to put in a good word for trying a book again another time. Ironically, this had been a DNF for me last summer: I found the prologue, with all its talk of the zodiac, utterly dull. I had the same problem with Cold Comfort Farm, literally trying about three times to get through the prologue and failing. So, for both, I eventually let myself skip the prologue, read the whole novel, and then go back to the prologue. Worked a treat.)

Source: Ex-library copy bought from Lambeth Library when I worked in London

My rating:

A contemporary readalike: Atonement by Ian McEwan

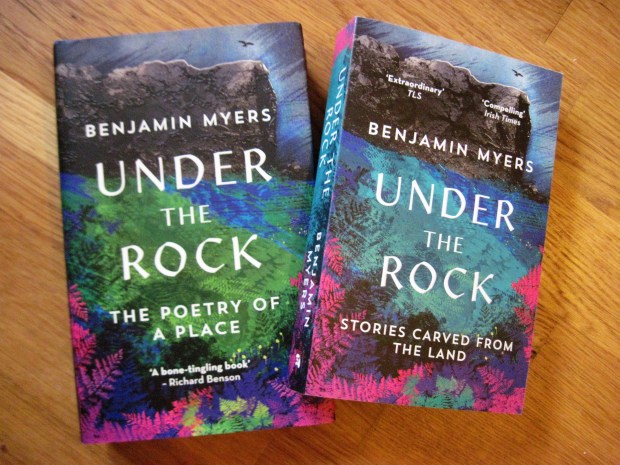

Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers: Paperback Giveaway

Benjamin Myers’s Under the Rock was my nonfiction book of 2018, so I’m delighted to be kicking off the blog tour for its paperback release on the 25th (with a new subtitle, “Stories Carved from the Land”). I’m reprinting my Shiny New Books review below, with permission, and on behalf of Elliott & Thompson I am also hosting a giveaway of a copy of the paperback. Leave a comment saying that you’d like to win and I will choose one entry at random at the end of the day on Tuesday the 30th. (Sorry, UK only.)

My review:

Benjamin Myers has been having a bit of a moment. In 2017 Bluemoose Books published his fifth novel, The Gallows Pole, which went on to win the Roger Deakin Award and the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction and is now on its fourth printing. This taste of fame has brought renewed attention to his earlier work, including Beastings (2014), recipient of the Northern Writers’ Award. I’ve been interested in Myers’s work ever since I read an extract from the then-unpublished The Gallows Pole in Autumn, the Wildlife Trusts anthology edited by Melissa Harrison, but this is the first of his books that I’ve managed to read.

“Unremarkable places are made remarkable by the minds that map them,” Myers writes, and that is certainly true of Scout Rock, a landmark overlooking Mytholmroyd, near where the author lives in the Calder Valley of West Yorkshire. When he moved up there from London over a decade ago, he and his wife lived in a rental cottage built in 1640. He approached his new patch with admirable curiosity, and supplemented the observations he made from his study window with frequent long walks with his dog, Heathcliff (“Walking is writing with your feet”), and research into the history of the area. The result is a divagating, lyrical book that ranges from geology to true crime but has an underlying autobiographical vein.

Ted Hughes was born nearby, the Brontës not that much further away, and Hebden Bridge, in particular, has become a bastion of avant-garde artists and musicians. Myers also gets plenty of mileage out of his eccentric neighbours and postman. It’s a town that seems to attract oddballs and renegades, from the vigilantes who poisoned the fishing hole to an overdose victim who turns up beneath a stand of Himalayan balsam. A strange preponderance of criminals has come from the region, too, including sexual offenders like Jimmy Savile and serial killers such as the Yorkshire Ripper and Harold Shipman (‘Doctor Death’).

On his walks Myers discovers the old town tip, still full of junk that won’t biodegrade for hundreds more years, and finds traces of the asbestos that was dumped by Acre Mill, creating a national scandal. This isn’t old-style nature writing in search of a few remaining unspoiled places. Instead, it’s part of a growing literary interest in the ‘edgelands’ between settlement and the wild – places where the human impact is undeniable but nature is creeping back in. (Other recent examples would be Common Ground by Rob Cowen, Landfill by Tim Dee, Edgelands by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, and Outskirts by John Grindrod.)

Under the Rock gives a keen sense of the seasons’ change and the seemingly inevitable melancholy that accompanies bad weather. A winter of non-stop rain left Myers nigh on delirious with flu; Storm Eva caused the Calder River to flood. He was a part of the effort to rescue trapped pensioners. Heartening as it is to see how the disaster brought people together – Sikh and Muslim charities and Syrian refugees were among the first to help – looting also resulted. One of the most remarkable things about this book is how Myers takes in such extremes of behaviour, along with mundanities, and makes them all part of a tapestry of life.

The book’s recurring themes tangle through all of the sections, even though it has been given a somewhat arbitrary four-part structure (Wood – Earth – Water – Rock). Interludes between these major parts transcribe Myers’s field notes, which are more like impromptu poems that he wrote in a notebook kept in his coat pocket. The artistry of these snippets of poetry is incredible given that they were written in situ, and their alliteration bleeds into his prose as well. My favourite of the poems was “On Lighting the First Fire”:

Autumn burns

the sky

the woods

the valley

death is everywhere

but beneath

the golden cloak

the seeds of

a summer’s

dreaming still sing.

The Field Notes sections are illustrated with Myers’s own photographs, which, again, are of enviable quality. I came away from this feeling like Myers could write anything – a thank-you note, a shopping list – and make it read as profound literature. Every sentence is well-crafted and memorable. There is also a wonderful sense of rhythm to his pages, with a pithy sentence appearing every couple of paragraphs to jolt you to attention.

“Writing is a form of alchemy,” Myers declares. “It’s a spell, and the writer is the magician.” I certainly fell under the author’s spell here. While his eyes are open to the many distressing political and environmental changes of the last few years, the ancient perspective of the Rock reminds him that, though humans are ultimately insignificant and individual lives are short, we can still rejoice in our experiences of the world’s beauty while we’re here.

From the publisher:

“Benjamin Myers was born in Durham in 1976. He is a prize-winning author, journalist and poet. His recent novels are each set in a different county of northern England, and are heavily inspired by rural landscapes, mythology, marginalised characters, morality, class, nature, dialect and post-industrialisation. They include The Gallows Pole, winner of the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction, and recipient of the Roger Deakin Award; Turning Blue, 2016; Beastings, 2014 (Portico Prize for Literature & Northern Writers’ Award winner), Pig Iron, 2012 (Gordon Burn Prize winner & Guardian Not the Booker Prize runner-up); and Richard, a Sunday Times Book of the Year 2010. Bloomsbury will publish his new novel, The Offing, in August 2019.

As a journalist, he has written widely about music, arts and nature. He lives in the Upper Calder Valley, West Yorkshire, the inspiration for Under the Rock.”

The Booker Dark Horse: Elmet by Fiona Mozley

The dark horse in this year’s Man Booker Prize race is Elmet, a brilliant, twisted fable about the clash of the land-owning and serf classes in contemporary England. I’d love to see this win the Booker, or make the shortlist at the very least. You’d hardly believe it’s a debut novel, or that it’s by a 29-year-old PhD candidate in medieval history. The epigraph from Ted Hughes defines “Elmet” as an ancient Celtic kingdom encompassing what is now West Yorkshire. The word still appears in a few Yorkshire place names today. Metaphorically, Hughes notes, the region was a “‘badlands’, a sanctuary for refugees from the law.” That’s an apt setting for Mozley’s central characters: a family living on the edge of poverty and respectability – off-grid and not quite legal.

Daniel and Cathy Oliver – 14 and 15, respectively – live with their father, John Smythe, in a simple house he built with his own hands in a copse. They mostly eat whatever they can hunt. Daddy is a renowned pugilist not above beating people up when they owe his friends money. Feisty Cathy is bullied by boys at school; when teachers don’t believe her, she has no choice but to hit back. There’s a strong us-against-the-world ethos to the novel, but underneath that defensiveness there’s a sense of unease: Daniel, the narrator, isn’t a fighter like his father and sister. He’s a sensitive soul who’s happiest cooking and playing with his dogs.

Daniel and Cathy Oliver – 14 and 15, respectively – live with their father, John Smythe, in a simple house he built with his own hands in a copse. They mostly eat whatever they can hunt. Daddy is a renowned pugilist not above beating people up when they owe his friends money. Feisty Cathy is bullied by boys at school; when teachers don’t believe her, she has no choice but to hit back. There’s a strong us-against-the-world ethos to the novel, but underneath that defensiveness there’s a sense of unease: Daniel, the narrator, isn’t a fighter like his father and sister. He’s a sensitive soul who’s happiest cooking and playing with his dogs.

Like the reader, Daniel watches in grim fascination as Mr. Price, a powerful local landlord, starts issuing threats. Price warns Daddy that his family is trespassing. If they don’t leave he’ll make life difficult for them. A group of tenants, many of them just out of prison and barely getting by, bands together to take revenge on Price, planning to withhold rent and farm labor until conditions improve. No longer will they accept £20 payments for 10-hour work days. At first it seems their fight for rights might be successful, but Price and his goons retrench. Things come to a head when Price promises to sign their plot of land over to Daniel – if Daddy agrees to call off the strike and fight one last climactic match in the woods.

The final 70 pages of Elmet blew me away: a crescendo of fateful violence that reaches Shakespearean proportions. This knocks all those Hogarth remakes (which generally, with the exception of Hag-Seed, adhere too slavishly to the plots and so fail to channel the spirit) into a cocked hat. Though oddly similar to two other novels on the Booker longlist that unearth disturbing doings in a superficially pastoral England – Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor and Autumn by Ali Smith – Elmet achieves the better balance between lush nature writing and Hardyesque pessimism. Mozley’s countryside is no idyll but a fallen edgeland:

And if the hare was made of myths then so too was the land at which she scratched. Now pocked with clutches of trees, once the whole county had been woodland and the ghosts of the ancient forest could be marked when the wind blew. The soil was alive with ruptured stories that cascaded and rotted then found form once more and pushed up through the undergrowth and back into our lives.

The characters usually speak in Yorkshire dialect, but where many authors would render the definite article as “t’,” Mozley simply elides it. For instance, here’s John shaking his head over the injustice of land ownership:

It’s idea a person can write summat on a bit of paper about a piece of land that lives and breathes, and changes and quakes and floods and dries, and that that person can use it as he will, or not at all, and that he can keep others off it, all because of a piece of paper. That’s part which means nowt to me.

The author is not entirely consistent with the transcription of dialect, though, and sometimes her use of spoken language is off: too ornate to be believable in certain characters’ mouths, like Cathy or a man who comes to the door to deliver bad news late on. These are such minor lapses of authorial control that I barely think them worth mentioning, but take it as proof that Mozley will only get better in the years to come. This is a gorgeous, timeless tale of the determination to overcome helplessness by facing down those who might harm the body but cannot destroy the spirit.

My rating:

Elmet was published in the UK by JM Originals on August 10th. With thanks to Yassine Belkacemi and Katherine Burdon at John Murray Press for the free review copy.

Literary Connections in Whitby

This past weekend marked my second trip to Whitby in North Yorkshire, more than 10 years after my first. It was, appropriately, on the occasion of a 10-year anniversary – namely, of the existence of Emmanuel Café Church, an informal group based at the University of Leeds chaplaincy center that I was involved in during my master’s year in 2005–6. I was there for the very first year and it was a welcome source of friendship during a tough year of loneliness and homesickness, so it’s gratifying that it’s still going nearly 11 years later (but also scary that it’s all quite that long ago). The reunion was held at Sneaton Castle, a lovely venue with a resident order of Anglican nuns that’s about a half-hour walk from central Whitby.

Sneaton Castle and grounds

Whitby harbor, with St. Mary’s Church on the hill.

The more I think about it, Leeds was a fine place to do a Victorian Literature degree – it’s not too far from Haworth, the home of the Brontës, or Whitby, a setting used in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Two of my classmates and I made our own pilgrimages to both sites in 2006. The Whitby Abbey ruins rising above the churchyard of St. Mary’s certainly create a suitably creepy atmosphere. No wonder Whitby is enduringly popular with Goths and at Halloween.

Another resident of Victorian Whitby, unknown to me until I saw a plaque designating her cottage on the walk from Sneaton into town, was Mary Linskill (1840–91), who wrote short stories and novels including Between the Heather and the Northern Sea (1884), The Haven under the Hill (1886) and In Exchange for a Soul (1887). I checked Project Gutenberg and couldn’t find a trace of her work, but the University of Reading holds a copy of her Tales of the North Riding in their off-site store. Perhaps I’ll have a gander!

There are other connections to be made with Whitby, too. For one thing, it has a long maritime history: it was home to William Scoresby (“Whaler, Arctic Voyager and Inventor of the Crow’s Nest,” as the plaque outside his house reads), and Captain James Cook grew up 30 miles away and served an apprenticeship in the town. There’s a statue of Cook plus a big whalebone arch on the hill the other side of the harbor from the church and abbey. It felt particularly fitting that I’ve been reading A.N. Wilson’s forthcoming novel Resolution, about the naturalists who sailed on Captain Cook’s second major expedition in the 1770s.

There are other connections to be made with Whitby, too. For one thing, it has a long maritime history: it was home to William Scoresby (“Whaler, Arctic Voyager and Inventor of the Crow’s Nest,” as the plaque outside his house reads), and Captain James Cook grew up 30 miles away and served an apprenticeship in the town. There’s a statue of Cook plus a big whalebone arch on the hill the other side of the harbor from the church and abbey. It felt particularly fitting that I’ve been reading A.N. Wilson’s forthcoming novel Resolution, about the naturalists who sailed on Captain Cook’s second major expedition in the 1770s.

(My other apt reading for the sunny August weekend was Vanessa Lafaye’s Summertime.)

On our Sunday afternoon browse of Whitby’s town center we couldn’t resist a stop into a bargain bookshop, where my husband bought a cheap copy of David Lebovitz’s all-desserts cookbook; I picked up a classy magnetic bookmark and a novel I’d never heard of for a grand total of £1.09. I know nothing about Dirk Wittenborn’s Pharmakon, but this 10 pence paperback comes with high praise from Lionel Shriver, Bret Easton Ellis and the Guardian, so I’ll give it a try and let you know how it works out in terms of literary value for money!

This was among my

This was among my  All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!)

All these years I’d had two 1989–1990 films conflated: Misery and My Left Foot. I’ve not seen either but as an impressionable young’un I made a mental mash-up of the posters’ stills into a film featuring Daniel Day-Lewis as a paralyzed writer and Kathy Bates as a madwoman wielding an axe. (Turns out the left foot is relevant!) This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues.

This is a reissue edition geared towards young adults. All but one of the 10 stories were originally published in literary magazines or anthologies. The stories are long, some approaching novella length, and took me quite a while to read. I got through the first three and will save the rest for next year. In “The Wrong Grave,” a teen decides to dig up his dead girlfriend’s casket to reclaim the poems he rashly buried with her last year – as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which Link makes a point of mentioning. A terrific blend of spookiness and comedy ensues. I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults (

I’d read all three of Paver’s previous horror novels for adults ( Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it.

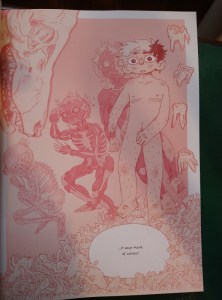

Ash is a trans man who starts working at a hole-in-the-wall ramen restaurant underneath a London railway arch. All he wants is to “pay for hormones, pay rent, [and] make enough to take a cutie on a date.” Bug’s Bones is run by an irascible elderly proprietor but staffed by a young multicultural bunch: Sock, Blue, Honey and Creamy. They quickly show Ash the ropes and within a month he’s turning out perfect bowls. He’s creeped out by the restaurant’s trademark bone broth, though, with its reminders of creatures turning into food. At the end of a drunken staff party, they find Bug lying dead and have to figure out what to do about it. This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award.

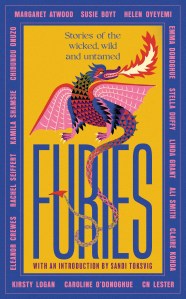

This storyline is in purple, whereas the alternating sequences of flashbacks are in a fleshy pinkish-red. As the two finally meet and meld, we see Ash trying to imitate the masculinity he sees on display while he waits for the surface to match what’s inside. I didn’t love the drawing style – though the full-page tableaux are a lot better than the high-school-sketchbook small panes – so that was an issue for me throughout, but this was an interesting, ghoulish take on the transmasc experience. Taylor won a First Graphic Novel Award. As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders. Susanna Jones’s

Susanna Jones’s  The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start.

The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start. The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins.

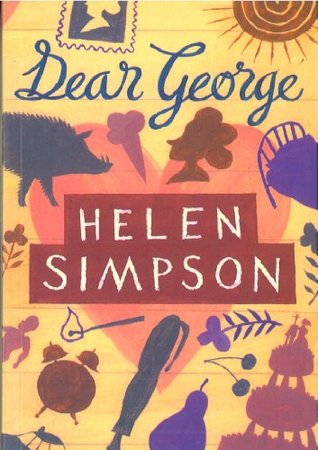

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins. This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after

This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after

Face to Face: True stories of life, death and transformation from my career as a facial surgeon by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more. McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. Here he pulls back the curtain on the everyday details of his work life: everything from his footwear (white Crocs that soon become stained with blood and other fluids) to his musical choices (pop for the early phases; classical for the more challenging microsurgery stage). Like neurosurgeon Henry Marsh, he describes the awe of the first incision – “an almost overwhelming sense of entering into a sanctuary.” There’s a vicarious thrill to being let into this insider zone, and the book’s prose is perfectly clear and conversational, with unexpectedly apt metaphors such as “Sometimes the blood vessels can be of such poor quality that it is like trying to sew together two damp cornflakes.” This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve.

Face to Face: True stories of life, death and transformation from my career as a facial surgeon by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more. McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. Here he pulls back the curtain on the everyday details of his work life: everything from his footwear (white Crocs that soon become stained with blood and other fluids) to his musical choices (pop for the early phases; classical for the more challenging microsurgery stage). Like neurosurgeon Henry Marsh, he describes the awe of the first incision – “an almost overwhelming sense of entering into a sanctuary.” There’s a vicarious thrill to being let into this insider zone, and the book’s prose is perfectly clear and conversational, with unexpectedly apt metaphors such as “Sometimes the blood vessels can be of such poor quality that it is like trying to sew together two damp cornflakes.” This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve.  On Sheep: Diary of a Swedish Shepherd by Axel Lindén: Lindén left city life behind to take on his parents’ rural collective in southeast Sweden. This documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. Published diaries can devolve into tedium, but the brevity and selectiveness of this one prevent its accounts of everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling, as the shepherd practices being present with these “quiet and unpretentious and stoical” creatures. The attention paid to slaughtering and sustainability issues – especially as the business starts scaling up and streamlining activities – lends the book a wider significance. It is thus more realistic and less twee than its stocking-stuffer dimensions and jolly title font seem to suggest.

On Sheep: Diary of a Swedish Shepherd by Axel Lindén: Lindén left city life behind to take on his parents’ rural collective in southeast Sweden. This documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. Published diaries can devolve into tedium, but the brevity and selectiveness of this one prevent its accounts of everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling, as the shepherd practices being present with these “quiet and unpretentious and stoical” creatures. The attention paid to slaughtering and sustainability issues – especially as the business starts scaling up and streamlining activities – lends the book a wider significance. It is thus more realistic and less twee than its stocking-stuffer dimensions and jolly title font seem to suggest.