March’s Doorstopper: Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese (2009)

I’m squeaking in here on the 31st with the doorstopper I’ve been reading all month. I started Cutting for Stone in an odd situation on the 1st: We’d attempted to go to France that morning but were foiled by a fatal engine failure en route to the ferry terminal, so were riding in the cab of a recovery vehicle that was taking us and our car home. My poor husband sat beside the driver, trying to make laddish small talk about cars, while I wedged myself by the window and got lost in the early pages of Indian-American doctor Abraham Verghese’s saga of twins Marion and Shiva, born of an unlikely union between an Indian nun, Sister Mary Joseph Praise, and an English surgeon, Thomas Stone, at Missing Hospital in Addis Ababa in 1954.

What with the flashbacks and the traumatic labor, it takes narrator Marion over 100 pages to get born. That might seem like a Tristram Shandy degree of circumlocution, but there was nary a moment when my interest flagged during this book’s 50-year journey with a medical family starting in a country I knew nothing about. I was reminded of Midnight’s Children, in that the twin brothers are born loosely conjoined at the head and ever after have a somewhat mystical connection, understanding each other’s thoughts even when they’re continents apart.

What with the flashbacks and the traumatic labor, it takes narrator Marion over 100 pages to get born. That might seem like a Tristram Shandy degree of circumlocution, but there was nary a moment when my interest flagged during this book’s 50-year journey with a medical family starting in a country I knew nothing about. I was reminded of Midnight’s Children, in that the twin brothers are born loosely conjoined at the head and ever after have a somewhat mystical connection, understanding each other’s thoughts even when they’re continents apart.

When Sister Mary Joseph Praise dies in childbirth and Stone absconds, the twins are raised by the hospital’s blunt obstetrician, Hema, and her husband, a surgeon named Ghosh. Both brothers follow their adoptive parents into medicine and gain knowledge of genitourinary matters. We observe a vasectomy, a breech birth, a C-section, and the aftermath of female genital mutilation. While Marion relocates to an inner-city New York hospital, Shiva stays in Ethiopia and becomes a world expert on vaginal fistulas. The novel I kept thinking about was The Cider House Rules, which is primarily about orphans and obstetrics, and I was smugly confirmed by finding Verghese’s thanks to his friend John Irving in the acknowledgments.

Ethiopia’s postcolonial history is a colorful background, with Verghese giving a bystander’s view of the military coup against the Emperor and the rise of the Eritrean liberation movement. Like Marion, the author is an Indian doctor who came of age in Ethiopia, a country he describes as a “juxtaposition of culture and brutality, this molding of the new out of the crucible of primeval mud.” Marion’s experiences in New York City and Boston then add on the immigrant’s perspective on life in the West in the 1980s onwards.

Naomi of Consumed by Ink predicted long ago that I’d love this, and she was right. Of course I thrilled to the accounts of medical procedures, such as an early live-donor liver transplant (this was shortlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize in 2009), but that wasn’t all that made Cutting for Stone such a winner for me. I can’t get enough of sprawling Dickensian stories in which coincidences abound (“The world turns on our every action, and our every omission, whether we know it or not”), minor characters have heroic roles to play, and humor and tragedy balance each other out, if ever so narrowly. (Besides Irving, think of books like The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne.) What I’m saying, as I strive to finish this inadequate review in the last hour of the last day of the month, is that this was just my sort of thing, and I hope I’ve convinced you that it might be yours, too.

Favorite lines:

Hema: “The Hippocratic oath is if you are sitting in London and drinking tea. No such oaths here in the jungle. I know my obligations.”

“Doubt is a first cousin to faith”

“A childhood at Missing imparted lessons about resilience, about fortitude, and about the fragility of life. I knew better than most children how little separate the world of health from that of disease, living flesh from the icy touch of the dead, the solid ground from treacherous bog.”

Page count: 667

My rating:

Next month: Since Easter falls in April and I’ve been wanting to read it for ages anyway, I’ve picked out The Resurrection of Joan Ashby by Cherise Wolas to start tomorrow.

Classic and Doorstopper of the Month: East of Eden by John Steinbeck (1952)

Look no further for the Great American Novel. Spanning from the Civil War to World War I and crossing the country from New England to California, East of Eden is just as wide-ranging in its subject matter, with an overarching theme of good and evil as it plays out in families and in individual souls. This weighty material – openly addressed in theological and philosophical terms in the course of the novel – is couched in something of a family saga that follows several generations of the Trasks and the Hamiltons. (Some spoilers follow.)

Cyrus Trask, Civil War amputee and fraudulent hero, has two sons. He sends his beloved boy, Adam, into the army during the Indian Wars. Adam’s half-brother Charles stays home to tend the family’s Connecticut farm. There’s a bitter sibling rivalry between them; more than once it looks like Charles might beat Adam to death. When Cyrus, now high up in military administration in Washington, dies and leaves his sons $100,000, Charles is suspicious. He’s sure their father stole the money, but Adam won’t accept that. Adam takes his inheritance and buys a ranch outside Salinas, California, taking with him his new wife Cathy, who turned up battered on the brothers’ doorstep and won’t reveal anything about her shadowy background.

Cathy is that rare thing: a female villain, and one with virtually no redeeming features. No sooner has she given birth to Adam’s twin sons than she runs off, shooting him in the shoulder to get away. Unbeknownst to Adam, who still idealizes a wife he knows nothing about, she gets work in a Salinas brothel and before long takes over as the madam. As her sons Aron and Cal grow up, they hear rumors that make them doubt their mother is buried back East, as their father claims. Aron is drawn to the Church and falls for a girl named Abra, whom he puts on a pedestal just as he does his ‘dead’ mother. Cal, a wanderer and schemer, is determined not to follow his mother into vice even though that seems like his fate.

The John Steinbeck House (his childhood home) in Salinas, CA. By Ken Lund [CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons.

This was a buddy read with my mother. We were surprised by how much philosophy and theology Steinbeck includes. The parallels with the Cain and Abel story (brought to mind by both sets of C & A Trask brothers) are not buried in the text for an observant reader to find, but discussed explicitly. My favorite character and the novel’s most straightforward hero is Lee, Adam’s loyal Chinese cook, who practically raises Cal and Aron. When we first meet him he’s speaking pidgin, as is expected of him, but around friends he drops the act and can be his nurturing and deeply intellectual self. With some fellow Chinese scholars he’s picked apart Genesis 4 and zeroed in on one Hebrew word, timshel or “thou mayest.” To Lee this speaks of choice and possibility; life is not all pre-ordained. For the two central families it is a message of hope: one does not have to replicate family mistakes.

Steinbeck with his third wife, Elaine Scott, in 1950. The character of Cathy may be based on his second wife, Gwyn Conger, who cheated on him on multiple occasions and asked for a divorce. [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

At 600 small-type pages, this is a big book with many minor threads and secondary characters I haven’t even touched on. Steinbeck grapples with primal stories about human nature and examines how we try to earn love and break free from others’ expectations. His depiction of America’s contradictions still feels true, and he writes simply stunning sentences. “It is one of the best books I’ve ever read,” my mother told me. It’s a classic you really shouldn’t pass up.

Page count: 602

My rating:

A few favorite passages:

“It is the dull eventless times that have no duration whatever. A time splashed with interest, wounded with tragedy, crevassed with joy—that’s the time that seems long in the memory.”

“Adam Trask grew up in grayness, and the curtains of his life were like dusty cobwebs, and his days a slow file of half-sorrows and sick dissatisfactions, and then, through Cathy, the glory came to him.”

“We have only one story. All novels, all poetry, are built on the never-ending contest in ourselves of good and evil. And it occurs to me that evil must constantly respawn, while good, while virtue, is immortal. Vice has always a new fresh young face, while virtue is venerable as nothing else in the world is.”

During the month I spent reading this I could hardly get these two songs out of my head. Both seem to be at least loosely inspired by East of Eden. I’ve pulled out some key lines and linked to audio or video footage.

When the clouds roll in, we start playing for our sins

With a gun in my hand and my son at my shoulder

Believe I will run before that boy gets older […]

Ask the angels, “Am I heaven-bound?”

“By the Skin of My Teeth” by Duke Special

My luck ran out just east of Eden

Oh, I proved you right

I’m a danger […]

I’m tired, don’t let me be a failure

Doorstopper(s) of the Month: Julia Glass (& Umberto Eco)

The Whole World Over by Julia Glass (2006)

When I plucked this from the sidewalk clearance area of my favorite U.S. bookstore, all I knew about it was that it featured a chef and was set in New York City and New Mexico. Those facts were enough to get me interested, and my first taste of Julia Glass’s fiction did not disappoint. I started reading it in the States at the very end of December and finished it in the middle of this month, gobbling up the last 250 pages or so all in one weekend.

Charlotte “Greenie” Duquette is happy enough with her life: a successful bakery in Greenwich Village, her psychiatrist husband Alan, and their young son George. But one February 29th – that anomalous day when anything might happen – she gets a call from the office of the governor of New Mexico, who tasted her famous coconut cake (sandwiched with lemon curd and glazed in brown sugar) at her friend Walter’s tavern and wants her to audition for a job as his personal chef at the governor’s mansion in Santa Fe. It’s just the right offer to shake up her stagnating career and marriage.

Charlotte “Greenie” Duquette is happy enough with her life: a successful bakery in Greenwich Village, her psychiatrist husband Alan, and their young son George. But one February 29th – that anomalous day when anything might happen – she gets a call from the office of the governor of New Mexico, who tasted her famous coconut cake (sandwiched with lemon curd and glazed in brown sugar) at her friend Walter’s tavern and wants her to audition for a job as his personal chef at the governor’s mansion in Santa Fe. It’s just the right offer to shake up her stagnating career and marriage.

One thing you can count on from a doorstopper, from Dickens onward, is that most of the many characters will be connected (“a collection of invisibly layered lives” is how Glass puts it). So: Walter’s lover is one of Alan’s patients; Fenno, the owner of a local bookstore, befriends both Alan and Saga, a possibly homeless young woman with brain damage who volunteers in animal rescue – along with Walter’s dog-walker, who’s dating his nephew; and so on. The title refers to how migrating birds circumnavigate the globe but always find their way home, and the same is true of these characters: no matter how far they stray – even as Greenie and Alan separately reopen past romances – the City always pulls them back.

My only real complaint about the novel is that it’s almost overstuffed: with great characters and their backstories, enticing subplots, and elements that seemed custom-made to appeal to me – baking, a restaurant, brain injury, the relatively recent history of the AIDS crisis, a secondhand bookstore, rescue dogs and cats, and much more. I especially loved the descriptions of multi-course meals and baking projects. Glass spins warm, effortless prose reminiscent of what I’ve read by Louise Miller and Carolyn Parkhurst. I will certainly read her first, best-known book, Three Junes, which won the National Book Award. I was also delighted to recall that I have her latest on my Kindle: A House Among the Trees, based on the life of Maurice Sendak.

All told, this was quite the bargain entertainment at 95 cents! Two small warnings: 1) if you haven’t read Three Junes, try not to learn too much about it – Glass likes to use recurring characters, and even a brief blurb (like what’s on the final page of my paperback; luckily, I didn’t come across it until the end) includes a spoiler about one character. 2) Glass is deliberately coy about when her book is set, and it’s important to not know for as long as possible. So don’t glance at the Library of Congress catalog record, which gives it away.

Page count: 560

My rating:

I started Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1983) with the best intentions of keeping up with Annabel’s buddy read. The first 50–100 pages really flew by and drew me into the mystery of a medieval abbey where monks keep getting murdered in hideous ways. I loved the Sherlockian shrewdness and tenacity of Brother William; the dutiful recording of his sidekick, narrator Adso of Melk; and the intertextual references to Borges’s idea of a library as a labyrinth. But at some point the historical and theological asides and the untranslated snippets of other languages (mostly Latin) began to defeat me, and I ended up just skimming most of the book. I’d recommend this if you liked Samantha Harvey’s The Western Wind, or if you fancy an astronomically more intelligent version of The Da Vinci Code.

I started Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1983) with the best intentions of keeping up with Annabel’s buddy read. The first 50–100 pages really flew by and drew me into the mystery of a medieval abbey where monks keep getting murdered in hideous ways. I loved the Sherlockian shrewdness and tenacity of Brother William; the dutiful recording of his sidekick, narrator Adso of Melk; and the intertextual references to Borges’s idea of a library as a labyrinth. But at some point the historical and theological asides and the untranslated snippets of other languages (mostly Latin) began to defeat me, and I ended up just skimming most of the book. I’d recommend this if you liked Samantha Harvey’s The Western Wind, or if you fancy an astronomically more intelligent version of The Da Vinci Code.

A favorite passage: “Books are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry. When we consider a book, we mustn’t ask ourselves what it says but what it means”

My rating:

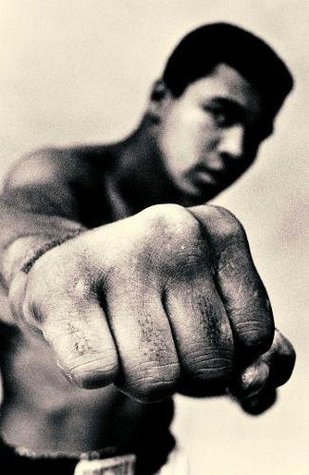

Biography of the Month: Ali: A Life by Jonathan Eig

The first book I ever reviewed on this blog, nearly three years ago, happened to be Jonathan Eig’s The Birth of the Pill. It was the strength of the writing in that offbeat work of history, as well as rave reviews for this 2017 biography of Muhammad Ali (1942–2016), that led me to pick up a sport-themed book. I’m the furthest thing from a sports fan you could imagine, but I approached this as a book about a cultural icon and read it with a spirit of curiosity about how Eig would shape this life story and separate the facts from the legend. It’s a riveting account of outliving segregation and developing a personal style and world-beating confidence; it’s a sobering tale of facing consequences and having your own body fail you. I loved it.

The first book I ever reviewed on this blog, nearly three years ago, happened to be Jonathan Eig’s The Birth of the Pill. It was the strength of the writing in that offbeat work of history, as well as rave reviews for this 2017 biography of Muhammad Ali (1942–2016), that led me to pick up a sport-themed book. I’m the furthest thing from a sports fan you could imagine, but I approached this as a book about a cultural icon and read it with a spirit of curiosity about how Eig would shape this life story and separate the facts from the legend. It’s a riveting account of outliving segregation and developing a personal style and world-beating confidence; it’s a sobering tale of facing consequences and having your own body fail you. I loved it.

Today would have been Ali’s 76th birthday, so in honor of the occasion – and his tendency to spout off-the-cuff rhymes about his competitors’ shortfalls and his own greatness – I’ve turned his life story into a book review of sorts, in rhyming couplets.

Born into 1940s Kentucky,

this fine boy had decent luck – he

surpassed his angry, cheating father

though he shared his name; no bother –

he’d not be Cassius Clay much longer.

He knew he was so much stronger

than all those other boys. Racing

the bus with Rudy; embracing

the help of a white policeman,

his first boxing coach – this guardian

prepared him for Olympic gold

(the last time Cassius did as told?).

A self-promoter from the start, he

was no scholar but won hearts; he

hogged every crowd’s full attention

but his faults are worth a mention:

he hoarded Caddys and Royces

and made bad financial choices;

he went through one, two, three, four wives

and lots of other dames besides;

his kids – no closer than his fans –

hardly even got a chance.

Cameos from bin Laden, Trump,

Toni Morrison and more: jump

ahead and you’ll see an actor,

envoy, entrepreneur, preacher,

recognized-all-round-the-world brand

(though maybe things got out of hand).

Ali was all things to all men

and fitted in the life of ten

but though he tested a lot of walks,

mostly he just wanted to box.

The fights: Frazier, Foreman, Liston –

they’re all here, and the details stun.

Eig gives a vivid blow-by-blow

such that you will feel like you know

what it’s like to be in the ring:

dodge, jab, weave; hear that left hook sing

past your ear. Catch rest at the ropes

but don’t stay too long like a dope.

If, like Ali, you sting and float,

keep an eye on your age and bloat –

the young, slim ones will catch you out.

Bow out before too many bouts.

Ignore the signs if you so choose

(ain’t got many brain cells to lose –

these blows to the head ain’t no joke);

retirement talk ain’t foolin’ folk,

can’t you give up on earning dough

and think more about your own soul?

1968 Esquire cover. By George Lois (Esquire Magazine) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons.

Allah laid a call on your head:

To raise up the black man’s status

and ask white men why they hate us;

to resist the Vietnam draft

though that nearly got you the shaft

and lost you your name, your title

and (close) your rank as an idol.

Was it all real, your piety?

Was it worth it in society?

Nation of Islam was your crew

but sure did leave you in the stew

with that Vietcong kerfuffle

and Malcolm/Muhammad shuffle.

Through U.S. missions (after 9/11)

you explained it ain’t about heaven

and who you’ll kill to get you there;

it’s about peace, being God’s heir.

Is this story all about race?

Eig believes it deserves its place

as the theme of Ali’s life: he

was born in segregation, see,

a black fighter in a white world,

but stereotypes he hurled

right back in their faces: Uncle

Tom Negro? Naw, even punch-drunk he’ll

smash your categories and crush

your expectations. You can flush

that flat dismissal down the john;

don’t think you know what’s going on.

Dupe, ego, clown, greedy, hero:

larger than life, Jesus or Nero?

How to see both, that’s the kicker;

Eig avoids ‘good’ and ‘bad’ stickers

but shows a life laid bare and

how win and lose ain’t fair and

history is of our making

and half of legacy is faking

and all you got to do is spin

the world round ’till it lets you in.

Biography’s all ’bout the arc

and though this story gets real dark,

there’s a glister to it all the same.

A man exists beyond the fame.

What do you know beneath the name?

Less, I’d make a bet, than you think.

Come over here and take a drink:

this is long, deep, satisfying;

you won’t escape without crying.

Based on 600 interviews,

this fresh account is full of news

and fit for all, not just sports fans.

Whew, let’s give it up for Eig, man.

My rating:

December’s Doorstopper: The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne

The more I examined the architecture of my life, the more I realized how fraudulent were its foundations.

This is a book that wasn’t even on my radar until fairly late on in the year, when I noticed just how many of my Goodreads friends had read it and rated it – almost without fail – 5 stars. I knew John Boyne’s name only through the movie version of his Holocaust-set novel for younger readers, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, and didn’t think I’d be interested in his work. But the fact that The Heart’s Invisible Furies was written in homage to John Irving (Boyne’s dedicatee) piqued my interest, and I’m so glad I gave it a try. It distills all the best of Irving’s tendencies while eschewing some of his more off-putting ones. Of the Irving novels I’ve read, this is most like The World According to Garp and In One Person, with which it shares, respectively, a strong mother–son relationship and a fairly explicit sexual theme.

A wonderful seam of humor tempers the awfulness of much of what befalls Cyril Avery, starting with his indifferent adoptive parents, Charles and Maude. Charles is a wealthy banker and incorrigible philanderer occasionally imprisoned for tax evasion, while Maude is a chain-smoking author whose novels, to her great disgust, are earning her a taste of celebrity. Both are cold and preoccupied, always quick to remind Cyril that since he’s adopted he’s “not a real Avery”. The first bright spot in Cyril’s life comes when, at age seven, he meets Julian Woodbead, the son of his father’s lawyer. They become lifelong friends, though Cyril’s feelings are complicated by an unrequited crush. Julian is as ardent a heterosexual as Cyril is a homosexual, and sex drives them apart in unexpected and ironic ways in the years to come.

A wonderful seam of humor tempers the awfulness of much of what befalls Cyril Avery, starting with his indifferent adoptive parents, Charles and Maude. Charles is a wealthy banker and incorrigible philanderer occasionally imprisoned for tax evasion, while Maude is a chain-smoking author whose novels, to her great disgust, are earning her a taste of celebrity. Both are cold and preoccupied, always quick to remind Cyril that since he’s adopted he’s “not a real Avery”. The first bright spot in Cyril’s life comes when, at age seven, he meets Julian Woodbead, the son of his father’s lawyer. They become lifelong friends, though Cyril’s feelings are complicated by an unrequited crush. Julian is as ardent a heterosexual as Cyril is a homosexual, and sex drives them apart in unexpected and ironic ways in the years to come.

For Cyril, born in Dublin in 1945, homosexuality seems a terrible curse. It was illegal in Ireland until 1993, so assignations had to be kept top-secret to avoid police persecution and general prejudice. Only when he leaves for Amsterdam and the USA is Cyril able to live the life he wants. The structure of the novel works very well: Boyne checks in on Cyril every seven years, starting with the year of his birth and ending in the year of his death. In every chapter we quickly adjust to a new time period, deftly and subtly marked out by a few details, and catch up on Cyril’s life. Sometimes we don’t see the most climactic moments; instead, we see what happened just before and then Cyril remembers the aftermath for us years later. It’s an effective tour through much of the twentieth century and beyond, punctuated by the AIDS crisis and focusing on the status of homosexuals in Ireland – in 2015 same-sex marriage was legalized, which would have seemed unimaginable a few short decades before.

Boyne also sustains a dramatic irony that kept me reading eagerly: the book opens with the story Cyril’s birth mother told him of her predicament in 1945, and in later chapters Cyril keeps running into this wonderfully indomitable woman in Dublin – but neither of them realizes how intimately they’re connected. Thanks to the first chapter we know they eventually meet and all will be revealed, but exactly when and how is a delicious mystery.

Along with Irving, Dickens must have been a major influence on Boyne. I spotted traces of David Copperfield and Great Expectations in minor characters’ quirks as well as in Cyril’s orphan status, excessive admiration of a romantic interest, and frequent maddening failures to do the right thing. But there are several other recent novels – all doorstoppers – that are remarkably similar in their central themes and questions. In Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life and Nathan Hill’s The Nix we also have absent or estranged mothers; friends, lovers and adoptive family who help cut through a life of sadness and pain; and the struggle against a fate that seems to force one to live a lie. Given a span of 500 pages or more, it’s easy to become thoroughly engrossed in the life of a flawed character.

The Heart’s Invisible Furies – a phrase Hannah Arendt used to describe the way W.H. Auden wore his experiences on his face – is an alternately heartbreaking and heartening portrait of a life lived in defiance of intolerance and tragedy. A very Irish sense of humor runs all through the dialogue and especially Maude’s stubborn objection to fame. I loved Boyne’s little in-jokes about the writer’s life (“It’s a hideous profession. Entered into by narcissists who think their pathetic little imaginations will be of interest to people they’ve never met”) and thanks to my recent travels I was able to picture a lot of the Dublin and Amsterdam settings. Although it’s been well reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic, I’m baffled that this novel doesn’t have the high profile it deserves. I am especially grateful to Sarah of Sarah’s Book Shelves for naming this her book of the year: knowing her discriminating tastes, I could tell I’d be in for something special. Look out for it on my Best Fiction of 2017 list tomorrow.

My rating:

I got just four books for Christmas this year, but they’re all ones I’m very excited to read. I looked back at last year’s Christmas book haul photo and am impressed that I’ve actually read seven out of eight of them now – and the eighth is a cocktail cookbook one wouldn’t read all the way through anyway. All too often I let books sit around for years unread, but I will try to keep up this trend of reading books fairly soon after they enter my collection.

As a God Might Be by Neil Griffiths

[Note: A shortened, edited version of this review appeared in the June 15th, 2018 issue of the Church Times.]

Proctor McCullough isn’t a churchgoer. He’s not even particularly religious. Yet somehow he senses that God is calling him to build a chapel, with a little house beside it, on a cliff in the southwest of England. It’s a source of bewilderment for his partner, Holly, and their London friends. Is Mac mentally ill, or having a particularly acute midlife crisis? He’s handed off from a minister to a therapist to a neurologist, but no one knows what to make of him. This forty-four-year-old father of two, an otherwise entirely rational-seeming advisor to the government on disaster situations, won’t be deterred from his mission.

It’s important to get a sense of the way this character speaks:

I want a structure that will move people to contemplate something other than all the obvious stuff … to be confronted with a sense of something and only be able to define it as Other.

God is the transcendent Other for whom creation, what we know as life, is a gratuitous act of love, a dispossession of a portion of His infinite creativity given over to our thriving. It is a gift from His infinite excess. That we can know Him at all is because of the possibility of this excess within us, which we experience as love, art, great feats of the mind. Our bounty is Him.

Down at the project site, Mac acquires four young workers/disciples: Rebecca, Nathaniel, Terry and Rich. Rebecca is a sarcastic, voluptuous teenager who will be off to Cambridge in a few months. She perhaps represents vanity, temptation and judgment, while the other three are more difficult to slot into symbolic roles. Terry is a dreadlocked lager lout who takes care of a mother with early dementia; contrary to appearances, he’s also a thinker, and takes to carrying around a Bible along with a collection of other theological works. Nat and Rich are more sketch-like figures, just ciphers really, which became problematic for me later on.

With Mac we shuttle between the building site and his home in London for weeks at a time. The idea of incorporating Pascal’s mystical hexagon into the church design captivates him, and the costs – initially set at £100,000 – balloon. Meanwhile, his relationship with Holly is strained almost to the breaking point as they each turn to alternative confidants, and there’s a renegotiation process as they decide whether their actions have torn them apart for good.

With Mac we shuttle between the building site and his home in London for weeks at a time. The idea of incorporating Pascal’s mystical hexagon into the church design captivates him, and the costs – initially set at £100,000 – balloon. Meanwhile, his relationship with Holly is strained almost to the breaking point as they each turn to alternative confidants, and there’s a renegotiation process as they decide whether their actions have torn them apart for good.

Like Sarah Moss, Neil Griffiths realistically blends serious concepts with everyday domestic tasks: sure, there may be a God-ordained chapel to build, but Mac also has to do the shopping and get his six-year-old twins fed and in bed at a decent hour. If Mac is meant to be a Messiah figure here, he’s a deeply flawed one; he can even be insufferable, especially when delivering his monologues on religion. If you’re like me, you’ll occasionally get incensed with him – particularly when, at the midpoint, he concocts a Clintonian justification for his behavior.

All the same, the themes and central characters were strong enough to keep me powering through this 600-page novel of ideas. Mac’s violent encounters with God and with the nature of evil are compelling, and although some of the events of the last third push the boundaries of credibility, it’s worth sticking with it to see where Griffiths takes the plot. There’s no getting past the fact that this is a dense theological treatise, but overlaid on it is a very human story of incidental families and how love sustains us through the unbearable.

If I had to point to the novel’s forebears, I’d mention Hamlet, A.S. Byatt’s The Virgin in the Garden, Michael Arditti’s Easter, and even Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. If you’ve read any Dostoevsky (I haven’t, yet) or Iris Murdoch, you’ll likely spot philosophical echoes. The title itself is from Wallace Stevens. It’s all unabashedly highbrow, and a greater than average familiarity with the Christian tradition is probably key. For the wary, I’d suggest not trying too hard to read metaphorical significance into character names or chapter and section titles – I’m sure those meanings are in there, but better to let the story carry you along rather than waste time trying to work it all out.

While reading this novel I was bitterly regretting the demise of Third Way magazine; it would have been a perfect place for me to engage with Griffiths’ envelope-pushing theology. I was also wishing I was still involved with Greenbelt Festival’s literature programming, as this would make a perfect Big Read. (Though however would we get people to read 600 pages?! In my experience of book clubs, it’s hard enough to get them to read 200.)

I’m grateful to Dodo Ink (“an independent UK publisher publishing daring and difficult fiction”) for stepping into the breach and taking a chance on a book that will divide Christians and the nonreligious alike, and to publicist Nicci Praça for the surprise copy that turned up on my doorstep. This turned out to be just my sort of book: big and brazen, a deep well of thought that will only give up its deeper meanings upon discussion and repeat readings.

My rating:

As a God Might Be was published in the UK by Dodo Ink on October 26th. This is Neil Griffiths’ third novel, after Betrayal in Naples (2004) and Saving Caravaggio (2006). He says that this most recent book took him seven years to write.

Better Late than Never: The Nix by Nathan Hill

I was wary of Nathan Hill’s debut novel, The Nix, as I always am of big ol’ books. Six hundred and twenty pages of small print: was it going to be worth it? Luckily, the answer was a resounding yes. If you’ve loved The World According to Garp, City on Fire, The Goldfinch, and/or Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist, you should pick this one up right away. From the first few pages onwards, I was impressed by Hill’s carefully honed sentences. He mixes up the paragraph arrangement in a particularly effective way, such that long thoughts are punctuated by a killer one-liner given a paragraph of its own. Here’s one: “How easily a simple façade can become your life, can become the truth of your life.”

In 2011 Samuel Anderson and his estranged mother, Faye, find themselves in strange situations. Samuel is an assistant English professor at a small suburban Chicago college. Once the Next Big Thing, feted by Granta for a brilliant short story, he has never delivered his contracted novel and spends more time in the World of Elfscape online game than he does engaging in real life. Now Laura Pottsdam, a student he caught plagiarizing a Hamlet essay, is on a mission to take Samuel down. Meanwhile Faye is awaiting trial for throwing rocks at Governor Packer, a conservative presidential hopeful from Wyoming. It’s been 23 years since Faye walked out on Samuel and his father, but her lawyer still hopes Samuel will be willing to write a character reference to be used in her defense, prompting their awkward reunion.

This is a rich, multi-layered story about family curses and failure, and how to make amends for a life full of mistakes. Along with 2011, the two main time periods are 1968, when Faye was a would-be radical caught up in student violence; and 1988, the summer before Faye left, when Samuel met twins Bishop and Bethany Fall, two friends who would still be having an impact on his life decades later even though they moved away after a few months. Although most of the action takes place in Iowa and Chicago, there’s also a brief interlude set in Norway when Faye tries to track down the ghosts of her father’s homeland. He’d told her stories of the nisse and the Nix, a house spirit and a water spirit in the form of a giant horse: both lead greedy children to their doom, a terrifying prospect for an anxious girl like Faye.

This is a rich, multi-layered story about family curses and failure, and how to make amends for a life full of mistakes. Along with 2011, the two main time periods are 1968, when Faye was a would-be radical caught up in student violence; and 1988, the summer before Faye left, when Samuel met twins Bishop and Bethany Fall, two friends who would still be having an impact on his life decades later even though they moved away after a few months. Although most of the action takes place in Iowa and Chicago, there’s also a brief interlude set in Norway when Faye tries to track down the ghosts of her father’s homeland. He’d told her stories of the nisse and the Nix, a house spirit and a water spirit in the form of a giant horse: both lead greedy children to their doom, a terrifying prospect for an anxious girl like Faye.

Political protest is a thread running all through the novel, though it never drowns out the centrality of the mother–son relationship: the 1968 Grant Park protest Faye attends in Chicago, the anti-Iraq War march Samuel and Bethany go on in 2004, the Occupy demonstrations taking place in 2011, and Faye’s odd transformation into the Packer Attacker. Hill makes cogent comments on contemporary America, where the “pastime is no longer baseball. Now it’s sanctimony.” Young people parcel emotions into easy categories for social media, which also markets ready-made heroes (pop singer Molly Miller) and villains (Faye).

Hill is a funny and inventive writer; a few of his more virtuosic moments include an argument with headings indicating its logical fallacies, a relationship presented as a Choose Your Own Adventure story, and a nearly-eleven-page sentence in which a character has a health crisis. These sections are almost too long – Come now, you’re just showing off, I thought. But changing up the structure like that does mean that the novel is never boring, and its reflections on self-knowledge and how we get lost, stuck in patterns of our own creating, made me think deeply. This is one debut that really does live up to the hype; look out for it, and for the upcoming television adaptation directed by J.J. Abrams and starring Meryl Streep.

My rating:

First published in August 2016, The Nix was released in the UK in paperback on September 21st. My thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Doorstopper of the Month: By Gaslight by Steven Price

My 2017 goal of reading one book of 500+ pages per month has been a mixed success. With the best doorstoppers the pages fly by and you enjoy every minute spent in a fictional world. From this past year Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle fits that bill, and a couple of novels I read years ago on holidays also come to mind: Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell and Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White. But then there are the books that feel like they’ll never end and you have to drag yourself through page by page.

Unfortunately, Steven Price’s second novel, By Gaslight, a Victorian cat-and-mouse mystery, tended more towards the latter group for me. Like Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, it has the kernel of a fascinating story but piles up the words unnecessarily. Between July and August I read the first 300 pages and then skimmed the rest (in total the paperback has 731 small-type pages). This is the story of William Pinkerton, a 39-year-old Civil War veteran and private investigator from Chicago who comes to London in 1885 to chase up a name from his father’s files: Edward Shade. His best lead comes to nothing when Charlotte Reckitt evades him and turns up as a set of dismembered remains in the Thames. Keeping in mind the rudimentary state of forensics, though, there’s some uncertainty about the corpse’s identity.

Unfortunately, Steven Price’s second novel, By Gaslight, a Victorian cat-and-mouse mystery, tended more towards the latter group for me. Like Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, it has the kernel of a fascinating story but piles up the words unnecessarily. Between July and August I read the first 300 pages and then skimmed the rest (in total the paperback has 731 small-type pages). This is the story of William Pinkerton, a 39-year-old Civil War veteran and private investigator from Chicago who comes to London in 1885 to chase up a name from his father’s files: Edward Shade. His best lead comes to nothing when Charlotte Reckitt evades him and turns up as a set of dismembered remains in the Thames. Keeping in mind the rudimentary state of forensics, though, there’s some uncertainty about the corpse’s identity.

The other central character in this drama is Adam Foole, a master thief. Half Indian and half English, he has violet eyes and travels in the company of Molly, a young pickpocket he passes off as his daughter, and Japheth Fludd, a vegetarian giant just out of prison. Foole was Charlotte’s lover ten years ago in South Africa, where they together pulled off a legendary diamond heist. Now he’s traveling back to England: she’s requested his help with a job as she knows she’s being tailed by a detective. The remaining cast is large and Dickensian: a medium and her lawyer brother, Charlotte’s imprisoned uncle, sewer dwellers, an opium dealer, and so on. Settings include a rare goods emporium, a Miss Havisham-type lonely manor house, the Record Office at Chancery Lane, and plenty of shabby garrets.

What I most enjoyed about the book was the restless, outlaw spirit of both main characters, but particularly Pinkerton. His troubled relationship with his father, in whose footsteps he’s following as a detective, is especially poignant: “William feared him and loved him and loathed him every day of his life yet too not a day passed that he did not want to be him.”

Price’s style is not what you’d generally expect of a Victorian pastiche. He uses no speech marks and his punctuation is non-standard, with lots of incomplete or run-in sentences like the one above. The critics’ blurbs liken By Gaslight to William Faulkner or Cormac McCarthy, apt comparisons that tell you just how unusual a hybrid it is.

I liked Price’s writing and starting around page 150 found the book truly gripping for a time, but extended flashbacks to Pinkerton and Foole’s earlier years really drag the story down, taking away from the suspense of the hunt. Meanwhile, the two major twists aren’t confirmed until over halfway through, but are hinted at so early that the watchful reader will know what’s going on long before the supposedly shrewd Pinkerton does. The salient facts about both characters’ past might have been conveyed in one short chapter each and the 1885 plot streamlined to make a taut novel of less than half the length.

There are many reasons to admire this Canadian novelist’s achievement, but whether it’s a reading experience you’d enjoy is something you’ll have to decide for yourself.

A favorite passage:

There is in every life a shadow of the possible, she said to him. The almost and the might have been. There are the histories that never were. We imagine we are keeping our accounts but what we are really saying is, I was here, I was real, this did happen once. It happened.

My rating:

By Gaslight was first published in the UK by Oneworld in September 2016. My thanks to Margot Weale for sending a free paperback for review.

Fun trivia: Steven Price is married to Esi Edugyan, author of the Booker Prize-shortlisted novel Half Blood Blues.

April 1945: Franklin D. Roosevelt is dead. His widow Eleanor goes to New York City to spend a long weekend with her lover, former White House reporter Lorena Hickok. Lorena, our feisty narrator, recalls her abusive upbringing in South Dakota, her early days as a reporter, and the flirtation that arose when she interviewed Eleanor about her governor husband’s presidential campaign. The open secret of FDR’s affair with his secretary, Missy LeHand, is contrasted with Eleanor and Lorena’s relationship – and with the situation of Eleanor’s cousin Parker Fiske, a closeted homosexual. Lorena’s voice is enjoyable, but I felt I gained no particular insight into Eleanor or Franklin Roosevelt. Bloom aims to reconcile Eleanor’s frumpy image with her passionate secret self, but for me that never fully happened. The most interesting scenes are from Lorena’s time working for a circus freak show on her way to Chicago (presumably completely made up). While Bloom had access to letters that passed between Lorena and Eleanor, she emphasizes that this is a work of fiction.

April 1945: Franklin D. Roosevelt is dead. His widow Eleanor goes to New York City to spend a long weekend with her lover, former White House reporter Lorena Hickok. Lorena, our feisty narrator, recalls her abusive upbringing in South Dakota, her early days as a reporter, and the flirtation that arose when she interviewed Eleanor about her governor husband’s presidential campaign. The open secret of FDR’s affair with his secretary, Missy LeHand, is contrasted with Eleanor and Lorena’s relationship – and with the situation of Eleanor’s cousin Parker Fiske, a closeted homosexual. Lorena’s voice is enjoyable, but I felt I gained no particular insight into Eleanor or Franklin Roosevelt. Bloom aims to reconcile Eleanor’s frumpy image with her passionate secret self, but for me that never fully happened. The most interesting scenes are from Lorena’s time working for a circus freak show on her way to Chicago (presumably completely made up). While Bloom had access to letters that passed between Lorena and Eleanor, she emphasizes that this is a work of fiction. I may be showing my political colors with this choice. However, in my defense, I have also read memoirs by Laura Bush and Sarah Palin, both of which, like this, are rumored to have been ghostwritten. (In her acknowledgments Clinton mentions Lissa Muscatine as “Responsible for many of the words in my speeches as First Lady and in this book”.) The first few chapters, about Clinton’s early years and college days, are rather plodding, but once she meets Bill at Yale Law School in 1971 things pick up, and I found the whole informative and diverting. I hadn’t realized that Clinton was an accomplished lawyer in her own right, focusing on women’s and children’s rights and family law. She was also a researcher on the Nixon impeachment case – an experience that, ironically, came in handy three decades later.

I may be showing my political colors with this choice. However, in my defense, I have also read memoirs by Laura Bush and Sarah Palin, both of which, like this, are rumored to have been ghostwritten. (In her acknowledgments Clinton mentions Lissa Muscatine as “Responsible for many of the words in my speeches as First Lady and in this book”.) The first few chapters, about Clinton’s early years and college days, are rather plodding, but once she meets Bill at Yale Law School in 1971 things pick up, and I found the whole informative and diverting. I hadn’t realized that Clinton was an accomplished lawyer in her own right, focusing on women’s and children’s rights and family law. She was also a researcher on the Nixon impeachment case – an experience that, ironically, came in handy three decades later. Roland Mesnier was the White House pastry chef for 25 years. After training in France and Germany, he worked at the Savoy in London and then as head pastry chef at the Princess Hotel, Bermuda – all by age 20. His specialty was intricate sugar sculptures, for which he won international competitions. He also worked in Paris and Virginia before hearing that Rosalynn Carter was looking for a White House pastry chef. Fast-tracked to U.S. citizenship, he made elaborate desserts for presidential family occasions and state dinners. The latter were always based on research into a particular country’s culture, products, taste and traditions. These impressive constructions included molded sorbets, petits fours and marzipan figures, and were often feats of logistics and timing. The memoir is undoubtedly more interesting for what it tells about the First Families (Nancy Reagan was a hard taskmistress; Barbara Bush was his personal #1) than for its author’s life. An appendix includes 15 fairly simple (i.e., replicable at home!) recipes from his 2004 cookbook Dessert University, such as pecan bourbon pie and baked apple soufflé.

Roland Mesnier was the White House pastry chef for 25 years. After training in France and Germany, he worked at the Savoy in London and then as head pastry chef at the Princess Hotel, Bermuda – all by age 20. His specialty was intricate sugar sculptures, for which he won international competitions. He also worked in Paris and Virginia before hearing that Rosalynn Carter was looking for a White House pastry chef. Fast-tracked to U.S. citizenship, he made elaborate desserts for presidential family occasions and state dinners. The latter were always based on research into a particular country’s culture, products, taste and traditions. These impressive constructions included molded sorbets, petits fours and marzipan figures, and were often feats of logistics and timing. The memoir is undoubtedly more interesting for what it tells about the First Families (Nancy Reagan was a hard taskmistress; Barbara Bush was his personal #1) than for its author’s life. An appendix includes 15 fairly simple (i.e., replicable at home!) recipes from his 2004 cookbook Dessert University, such as pecan bourbon pie and baked apple soufflé. (I must also marvel at the journey that this particular book has been on. It is signed by the English translator and inscribed to her mother: “Mum, with all love, Louise – 8 May 2007”. This hardback copy somehow made it all the way to the £1 bargain shelves outside the upper level of the castle in Hay-on-Wye, Wales, where my husband snatched it up last spring.)

(I must also marvel at the journey that this particular book has been on. It is signed by the English translator and inscribed to her mother: “Mum, with all love, Louise – 8 May 2007”. This hardback copy somehow made it all the way to the £1 bargain shelves outside the upper level of the castle in Hay-on-Wye, Wales, where my husband snatched it up last spring.) U.S. history has never been so much fun! There’s nothing Sarah Vowell loves more than a presidential plaque, monument, home or grave, and her enthusiasm is infectious. Over half of this book is about Abraham Lincoln’s assassination; the rest goes to those of James Garfield and William McKinley (attempts on T. Roosevelt and Reagan get a brief mention, but she pretty much avoids JFK – presumably because that would fill a book of its own). If all you remember about these last two assassins is that one was a disgruntled civil servant and the other was an anarchist with a funny name, let Vowell enlighten you with her mixture of travel and trivia. She follows John Wilkes Booth’s escape route from the nation’s capital, traces Charles Guiteau back to upstate New York’s Oneida community, and sympathizes with Leon Czolgosz’s hard early life. The book came out in 2005, and what with Vowell’s outrage over the Dubya administration, it does feel a little dated. But if the rest of her books are this nerdy-cool, I’ll be reading them all.

U.S. history has never been so much fun! There’s nothing Sarah Vowell loves more than a presidential plaque, monument, home or grave, and her enthusiasm is infectious. Over half of this book is about Abraham Lincoln’s assassination; the rest goes to those of James Garfield and William McKinley (attempts on T. Roosevelt and Reagan get a brief mention, but she pretty much avoids JFK – presumably because that would fill a book of its own). If all you remember about these last two assassins is that one was a disgruntled civil servant and the other was an anarchist with a funny name, let Vowell enlighten you with her mixture of travel and trivia. She follows John Wilkes Booth’s escape route from the nation’s capital, traces Charles Guiteau back to upstate New York’s Oneida community, and sympathizes with Leon Czolgosz’s hard early life. The book came out in 2005, and what with Vowell’s outrage over the Dubya administration, it does feel a little dated. But if the rest of her books are this nerdy-cool, I’ll be reading them all.

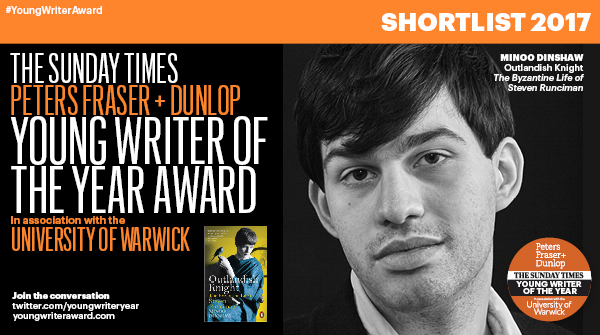

Dinshaw draws a fine distinction between his subject’s professional and private selves. When talking about the published historian and thinker, he uses “Runciman”; when talking about the closeted homosexual and his relationships with family and friends, it’s “Steven”. This confused me to start with, but quickly became second nature. Occasionally these public and private personas are contrasted directly: “Runciman was a great romantic historian; but in his personal affairs Steven had come to be more admiring of that epithet ‘realistic’ than of any height of romance.” Indeed, Steven once confessed he had never been in love. At the shortlist event on Saturday, Dinshaw summed him up as “an old-fashioned, courtly queer.”

Dinshaw draws a fine distinction between his subject’s professional and private selves. When talking about the published historian and thinker, he uses “Runciman”; when talking about the closeted homosexual and his relationships with family and friends, it’s “Steven”. This confused me to start with, but quickly became second nature. Occasionally these public and private personas are contrasted directly: “Runciman was a great romantic historian; but in his personal affairs Steven had come to be more admiring of that epithet ‘realistic’ than of any height of romance.” Indeed, Steven once confessed he had never been in love. At the shortlist event on Saturday, Dinshaw summed him up as “an old-fashioned, courtly queer.” Chapter titles are mainly taken from relevant tarot cards (for instance, Chapter 22, “The Hanged Man,” primarily concerns Steven’s homosexuality), which also feature on the book’s endpapers. The text is also partitioned by two sets of glossy black-and-white photographs. The book’s scope and the years of research that went into it cannot fail to impress. I never warmed to Steven as much as I wanted to, but that is likely due to a lack of engagement: regrettably, I had to skim much of the book to make the deadline. However, I will not be at all surprised if the official judges choose to honor this imposing work of scholarship.

Chapter titles are mainly taken from relevant tarot cards (for instance, Chapter 22, “The Hanged Man,” primarily concerns Steven’s homosexuality), which also feature on the book’s endpapers. The text is also partitioned by two sets of glossy black-and-white photographs. The book’s scope and the years of research that went into it cannot fail to impress. I never warmed to Steven as much as I wanted to, but that is likely due to a lack of engagement: regrettably, I had to skim much of the book to make the deadline. However, I will not be at all surprised if the official judges choose to honor this imposing work of scholarship.

I loved the premise of the novel, and its witty writing should appeal to Terry Pratchett and Nicola Barker fans. The more fantastical elements are generally brought back to earth by unremitting bureaucracy – I especially enjoyed a scene in which Charlie is questioned by U.S. Border officials. But the book’s structure and style got in the way for me. It is episodic and told via super-short chapters (110 of them). It skips around in a distracting manner, never landing on one scene or subplot for very long. Ellipses, partial repeated lines, and snippets of other voices all contribute to it feeling scattered and aimless. North’s

I loved the premise of the novel, and its witty writing should appeal to Terry Pratchett and Nicola Barker fans. The more fantastical elements are generally brought back to earth by unremitting bureaucracy – I especially enjoyed a scene in which Charlie is questioned by U.S. Border officials. But the book’s structure and style got in the way for me. It is episodic and told via super-short chapters (110 of them). It skips around in a distracting manner, never landing on one scene or subplot for very long. Ellipses, partial repeated lines, and snippets of other voices all contribute to it feeling scattered and aimless. North’s