Love Your Library, December 2022

The UK has just experienced its coldest week since 2010, so it’s no wonder we’ve been freezing here in our drafty old house. It’s turning milder (and rainy), so we hope to have it habitable for hosting my parents-in-law on Christmas day, and my sister the week after.

Margaret sent me a link to this charming story about a public library in Poland that moved its entire collection 350 meters down the road using a human chain of over 600 volunteers. Marcie sourced many of her graphic novel and poetry reads, as well as various globe-trotting stories, from the library this year. And Eleanor has been reading loads of print and e-books from her library: everything from Dickens to sci-fi. Thank you all for your contributions!

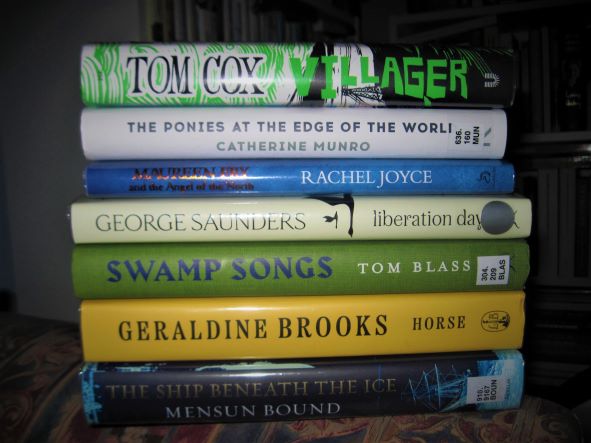

Earlier in the month my library closed to the public for two days to complete a stock take (which happens once every three years). I helped out for my usual two hours on the Tuesday morning, scanning children’s chapter books with a tiny device about the size of two memory sticks put together. We scanned the library’s nearly 50,000 on-shelf items in the equivalent of just over one working day.

All of my remaining reservations seem to have come in at once. There’s no hope of me reading all the big-name 2022 releases (such as the Booker Prize winner, and Celeste Ng’s new novel) before the end of the year, but I will see if I can manage to finish a few more that I have in progress.

Since last month:

READ

- Pages & Co.: The Treehouse Library by Anna James

- Heat and Dust by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

- Maureen Fry and the Angel of the North by Rachel Joyce

- Everything the Light Touches by Janice Pariat

- Leap Year by Helen Russell

- The Family Retreat by Bev Thomas

- Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson

CURRENTLY READING

- Horse by Geraldine Brooks

- A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney

- Leila and the Blue Fox by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

- Standard Deviation by Katherine Heiny

- Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Lessons by Ian McEwan

- Liberation Day by George Saunders

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

December Reading Plans

November is always a busy blogging month what with co-hosting Novellas in November and making small contributions to several other challenges: Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, and Margaret Atwood Reading Month.

In the final month of the year, my ambitions are always split:

I want to get to as many 2022 releases as possible … but I also want to dip a toe into the 2023 offerings.

I need to work on my review copy backlog … but I also want to relax and read some cosy wintry or holiday-themed stuff.

I want to get to the library books I’ve had out for ages … but I also want to spend some time reading from my shelves.

And that’s not even to mention my second year of McKitterick Prize judging (my manuscript longlist is due at the end of January).

My set-aside shelves (yes, literal shelves plural) are beyond ridiculous, and I have another partial shelf of review books not yet started. I do feel bad that I’ve accepted so many 2022 books for review and not read them, let alone reviewed them. But books are patient, and I’m going to cut myself some slack given that my year has contained two of the most stressful events possible (buying and moving into a house, and the death of a close family member).

I’m not even going to show you my preposterous backlog, because my WordPress media library is at capacity. “Looks like you have used 3.0 GB of your 3.0 GB upload limit (99%).” I’ll have to work on deleting lots of old images later on this month so that I can post photos of my best-of stacks towards the end of the year.

So, for December I’ll work a bit on all of the above. My one final challenge to self is “Diverse December” – not official since 2020, when Naomi Frisby spearheaded it, but worth doing anyway. This is the second year that I’ve specifically monitored my reading of BIPOC authors. Last year, I managed 18.5%. I have no idea where I stand now, but would like to see a higher total.

So, for December I’ll work a bit on all of the above. My one final challenge to self is “Diverse December” – not official since 2020, when Naomi Frisby spearheaded it, but worth doing anyway. This is the second year that I’ve specifically monitored my reading of BIPOC authors. Last year, I managed 18.5%. I have no idea where I stand now, but would like to see a higher total.

I’ll start with a December review book, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times by Meron Hadero, and see how I go from there. I was a lucky recipient of a proof copy of The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor, one of my new favourite authors; it doesn’t come out until May 23 in the USA and June 22 in the UK, but I will also see if I can read it early. Another potential 2023 release I have by a BIPOC author is Camp Zero by Michelle Min Sterling, a debut dystopian novel about climate refugees, which arrived unsolicited last month.

I’ll start with a December review book, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times by Meron Hadero, and see how I go from there. I was a lucky recipient of a proof copy of The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor, one of my new favourite authors; it doesn’t come out until May 23 in the USA and June 22 in the UK, but I will also see if I can read it early. Another potential 2023 release I have by a BIPOC author is Camp Zero by Michelle Min Sterling, a debut dystopian novel about climate refugees, which arrived unsolicited last month.

Among the other tempting options on my dedicated BIPOC-author shelf:

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam

Black Buck by Mateo Askaripour

Fruit of the Drunken Tree by Ingrid Rojas Contreras

The Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai

Diamond Hill by Kit Fan

A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry

Still Born by Guadalupe Nettel

The Last of Her Kind by Sigrid Nunez

Names of the Women by Jeet Thayil

What are your year-end bookish plans? Happy December reading!

January Releases, Part III: Taylor Harris, Cathy Rentzenbrink & Tanya Shadrick

Rounding off my three-part look at some of the month’s new releases with two memoirs plus a memoir-writer’s self-help guide today. (Can you tell I’m a memoir junkie?) Topics range from medical mysteries and covert racism to a reclaiming of life after a near-death experience, but these three nonfiction works by women are linked by the determination to overcome self-doubt.

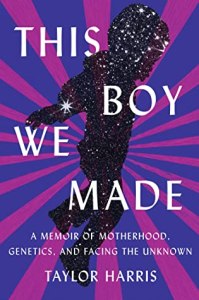

This Boy We Made: A Memoir of Motherhood, Genetics, and Facing the Unknown by Taylor Harris

One morning, Taylor Harris and her husband (an African American family based in Charlottesville, Virginia) found their 22-month-old son Christopher, nicknamed “Tophs,” awake but unresponsive in his crib. In the years that followed, she and his doctors looked for answers as to why his body couldn’t regulate his blood sugar levels, sometimes leading to seizures, and to why his speech and mental processing remained delayed. All their tests and theories have never amounted to a conclusive diagnosis. This was a book that repeatedly surprised me. I’d assumed it would be exclusively about the medical mystery of Tophs’s physical and intellectual disability. But Harris elegantly weaves in a lot of other themes, too: mental illness, her own physical concerns (a BRCA2 mutation), racism, faith, and advocating for her children’s health and education. (Full review at BookBrowse.)

One morning, Taylor Harris and her husband (an African American family based in Charlottesville, Virginia) found their 22-month-old son Christopher, nicknamed “Tophs,” awake but unresponsive in his crib. In the years that followed, she and his doctors looked for answers as to why his body couldn’t regulate his blood sugar levels, sometimes leading to seizures, and to why his speech and mental processing remained delayed. All their tests and theories have never amounted to a conclusive diagnosis. This was a book that repeatedly surprised me. I’d assumed it would be exclusively about the medical mystery of Tophs’s physical and intellectual disability. But Harris elegantly weaves in a lot of other themes, too: mental illness, her own physical concerns (a BRCA2 mutation), racism, faith, and advocating for her children’s health and education. (Full review at BookBrowse.)

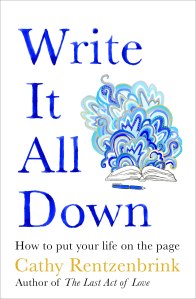

Write It All Down: How to put your life on the page by Cathy Rentzenbrink

Cathy Rentzenbrink is a lovely human being, and I’ve always appreciated her enthusiastic support of books. I’ve read all of her work even though I’ve been disappointed with her last few releases. There are so many writing guides out there – including several on memoir-writing specifically – that the first question to ask about one is, does it offer anything new? For me, this one doesn’t. In fact, it’s more of a therapy session than a practical writing guide.

The undemanding prose slides right down, but 60 pages in (at the end of Part One, “Preparation”) I realized all we’d had thus far was enumerating and countering the hang-ups of unconfident, procrastinating would-be writers. The rest of the book does then get into the nitty-gritty of producing a first draft (“Excavation”) of a life story and editing it into a more polished form. Rentzenbrink peppers in little tricks to keep oneself at the desk, like setting a timer or micro-goals, writing a section in the form of a letter, and dredging up sensory details. Most of the mini chapters are just a couple of pages. Several end with a series of prompts. I’m notorious for skipping the application questions in self-help books, but I’d be interested to hear if other readers have actually gone through these exercises and found them helpful.

The undemanding prose slides right down, but 60 pages in (at the end of Part One, “Preparation”) I realized all we’d had thus far was enumerating and countering the hang-ups of unconfident, procrastinating would-be writers. The rest of the book does then get into the nitty-gritty of producing a first draft (“Excavation”) of a life story and editing it into a more polished form. Rentzenbrink peppers in little tricks to keep oneself at the desk, like setting a timer or micro-goals, writing a section in the form of a letter, and dredging up sensory details. Most of the mini chapters are just a couple of pages. Several end with a series of prompts. I’m notorious for skipping the application questions in self-help books, but I’d be interested to hear if other readers have actually gone through these exercises and found them helpful.

I’m so familiar with the author’s own story from her three autobiographical works that I was less than patient about encountering certain incidents again here – though I was intrigued to learn that she gave up alcohol in the recent past after realizing that she was a problem drinker. I’ve also read most of the material in her Further Reading list; all told, I didn’t feel this book offered me much, as a lay reader or a maybe-some-day memoirist. But it seems to have been enormously popular among critics and readers (its average Goodreads rating is 4.38), so clearly a lot of people have been finding Rentzenbrink’s down-to-earth approach reassuring.

With thanks to Emma Finnigan PR and Bluebird for the proof copy for review.

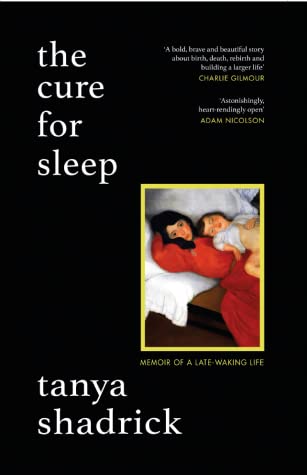

The Cure for Sleep: Memoir of a Late-Waking Life by Tanya Shadrick

From my Most Anticipated list. Shadrick hangs around the fringes of nature writing cliques on Twitter, so I expected this to have more of a nature/travel element. Instead, it bears a fairy tale ambience, of a little girl lost in the woods and craving freedom; of a sleepwalking woman deciding to live more deliberately. It opens with a near-death experience: Shadrick, new mother to a son conceived after infertility treatment, suffered a severe haemorrhage after the placenta tore an artery and was rushed to hospital for emergency surgery.

From this point she returns to the beginning of her life and proceeds chronologically, pausing at joyful or traumatic moments. Her childhood feels like the key to understanding everything else: her father left when she was a baby; her mother, all too aware of being of lower class, was driven to improve herself. Shadrick wanted her mother all to herself, at the same time as she felt trapped by her. She injured herself jumping off an outhouse roof in protest at her mother’s new boyfriend, who became her stepfather. At university she reacted against her upbringing in predictable ways, failing her first year and having an abortion. Even once happily married, she kept unconsciously searching for surrogate father (older male) figures.

From this point she returns to the beginning of her life and proceeds chronologically, pausing at joyful or traumatic moments. Her childhood feels like the key to understanding everything else: her father left when she was a baby; her mother, all too aware of being of lower class, was driven to improve herself. Shadrick wanted her mother all to herself, at the same time as she felt trapped by her. She injured herself jumping off an outhouse roof in protest at her mother’s new boyfriend, who became her stepfather. At university she reacted against her upbringing in predictable ways, failing her first year and having an abortion. Even once happily married, she kept unconsciously searching for surrogate father (older male) figures.

After the postnatal operation, she felt a need to escape – by suicide if necessary – yet forced herself to stay, make connections in her town and be present for her children. But she remained a free spirit, swimming and writing a mile-long scroll as public performance art. Her work with hospice patients, recording their memories, qualified her to edit Lynne Roper’s wild swimming diaries into a Wainwright Prize-longlisted book.

Awakening versus sleep is the figurative framework for the memoir, with a feminist insistence on freedom and self-fulfilment at the same time as being a mother. This is an unusual book – at times overwritten and too deliberately moulded into tropes as a rebuttal to randomness, even though, looking back, I can’t decipher a coherent plot to the events – that reminded me most of Free Woman by Lara Feigel and I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell.

With thanks to W&N for the free copy for review.

Does one of these books appeal to you?

January 2022 Releases, Part I: Jami Attenberg and Roopa Farooki

It’s been a big month for new releases! I’m still working on a handful and will report back on two batches of three, tomorrow and Sunday; more will likely turn up in review roundups in future months. For today, I have a memoir in essays about a peripatetic writer’s life and an excerpt from my review of a junior doctor’s chronicle of the early days of the pandemic.

I Came All This Way to Meet You: Writing Myself Home by Jami Attenberg

I’ve enjoyed Attenberg’s four most recent novels (reviewed here: The Middlesteins and All This Could Be Yours) so was intrigued to hear that she was trying out nonfiction. She self-describes as a “moderately successful author,” now in her early fifties – a single, independent feminist based in New Orleans after years in Manhattan and then Brooklyn. (Name-dropping of author friends: “Lauren” (Groff), “Kristen” (Arnett) and “Viola” (di Grado), with whom she stays in Italy.) Leaving places abruptly had become a habit; travelling from literary festival to holiday to writing residency was her way of counterbalancing a safe, quiet writing life at home. She tells of visiting a friend in Hong Kong and teaching fiction for two weeks in Vilnius – where she learned that, despite her Jewish heritage, Holocaust tourism is not her thing. Anxiety starts to interfere with travel, though, and she takes six months off flying. Owning a New Orleans home where she can host guests is the most rooted she’s ever been.

I’ve enjoyed Attenberg’s four most recent novels (reviewed here: The Middlesteins and All This Could Be Yours) so was intrigued to hear that she was trying out nonfiction. She self-describes as a “moderately successful author,” now in her early fifties – a single, independent feminist based in New Orleans after years in Manhattan and then Brooklyn. (Name-dropping of author friends: “Lauren” (Groff), “Kristen” (Arnett) and “Viola” (di Grado), with whom she stays in Italy.) Leaving places abruptly had become a habit; travelling from literary festival to holiday to writing residency was her way of counterbalancing a safe, quiet writing life at home. She tells of visiting a friend in Hong Kong and teaching fiction for two weeks in Vilnius – where she learned that, despite her Jewish heritage, Holocaust tourism is not her thing. Anxiety starts to interfere with travel, though, and she takes six months off flying. Owning a New Orleans home where she can host guests is the most rooted she’s ever been.

Along with nomadism, creativity and being a woman are key themes. Attenberg notices how she’s treated differently from male writers at literary events, and sometimes has to counter antifeminist perspectives even from women – as in a bizarre debate she ended up taking part in at a festival in Portugal. She takes risks and gets hurt, physically and emotionally. Break-ups sting, but she moves on and tries to be a better person. There are a lot of hard-hitting one-liners about the writing life and learning to be comfortable in one’s (middle-aged) body:

I believe that one must arrive at an intersection of hunger and fear to make great art.

Who was I hiding from? I was only ever going to be me. I was only ever going to have this body forever. Life was too short not to have radical acceptance of my body.

Whenever my life turns into any kind of cliché, I am furious. Not me, I want to scream. Not me, I am special and unusual. But none of us are special and unusual. Our stories are all the same. It is just how you tell them that makes them worth hearing again.

I did not know yet how books would save me over and over again. I did not know that a book was a reason to live. I did not know that being alive was a reason to live.

Late on comes her #MeToo story, which in some ways feels like the core of the book. When she was in college, a creative writing classmate assaulted her on campus while drunk. She reported it but nothing was ever done; it only led to rumours and meanness towards her, and a year later she attempted suicide. You know how people will walk into a doctor’s appointment and discuss three random things, then casually drop in a fourth that is actually their overriding concern? I felt that way about this episode: that really the assault was what Attenberg wanted to talk about, and could have devoted much more of the book to.

The chapters are more like mini essays, flitting between locations and experiences in the same way she has done, and sometimes repeating incidents. I think the intent was to mimic, and embrace, the random shape that a life takes. Each vignette is like a competently crafted magazine piece, but the whole is no more than the sum of the parts.

With thanks to Serpent’s Tail for the proof copy for review.

Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki

Farooki is a novelist, lecturer, mum of four, and junior doctor. Her storytelling choices owe more to literary fiction than to impassive reportage. The second-person, present-tense narration drops readers right into her position. Frequent line breaks and repetition almost give the prose the rhythm of performance poetry. There is also wry humour, wordplay, slang and cursing. In February 2020, her sister Kiron had died of breast cancer. During the first 40 days of the initial UK lockdown – the book’s limited timeframe – she continues to talk to Kiron, and imagines she can hear her sister’s chiding replies. Grief opens the door for magic realism, despite the title – which comes from a Balzac quote. A hybrid work that reads as fluidly as a novel while dramatizing real events, this is sure to appeal to people who wouldn’t normally pick up a bereavement or medical memoir. (Full review coming soon at Shiny New Books.)

Farooki is a novelist, lecturer, mum of four, and junior doctor. Her storytelling choices owe more to literary fiction than to impassive reportage. The second-person, present-tense narration drops readers right into her position. Frequent line breaks and repetition almost give the prose the rhythm of performance poetry. There is also wry humour, wordplay, slang and cursing. In February 2020, her sister Kiron had died of breast cancer. During the first 40 days of the initial UK lockdown – the book’s limited timeframe – she continues to talk to Kiron, and imagines she can hear her sister’s chiding replies. Grief opens the door for magic realism, despite the title – which comes from a Balzac quote. A hybrid work that reads as fluidly as a novel while dramatizing real events, this is sure to appeal to people who wouldn’t normally pick up a bereavement or medical memoir. (Full review coming soon at Shiny New Books.)

A great addition to my Covid chronicles repertoire!

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

Would one of these books interest you?

The Hero of This Book

The Hero of This Book

Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble by Carolyn Oliver: Carolyn used to blog at

Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble by Carolyn Oliver: Carolyn used to blog at

“Until the future, whatever it was going to be.” (This Time Tomorrow, Emma Straub)

“Until the future, whatever it was going to be.” (This Time Tomorrow, Emma Straub)

for me)

for me)

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

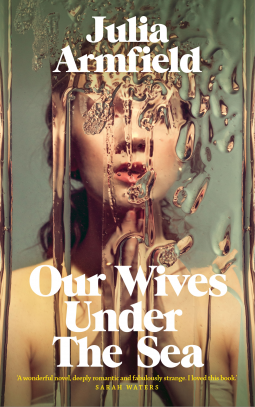

Miri is relieved to have her wife back when Leah returns from an extended Centre for Marine Inquiry expedition. But something went wrong with the craft while in the ocean depths and it was too late to evacuate. What happened to Leah and the rest of the small crew? Miri starts to worry that Leah – who now spends 70% of her time in the bathtub – will never truly recover. Chapters alternate between Miri describing their new abnormal and Leah recalling the voyage. As Miri tries to tackle life admin for both of them, she feels increasingly alone and doesn’t know how to deal with persistent calls from the sister of one of the crew members.

Miri is relieved to have her wife back when Leah returns from an extended Centre for Marine Inquiry expedition. But something went wrong with the craft while in the ocean depths and it was too late to evacuate. What happened to Leah and the rest of the small crew? Miri starts to worry that Leah – who now spends 70% of her time in the bathtub – will never truly recover. Chapters alternate between Miri describing their new abnormal and Leah recalling the voyage. As Miri tries to tackle life admin for both of them, she feels increasingly alone and doesn’t know how to deal with persistent calls from the sister of one of the crew members. The same intimate understanding of emotions and interactions found in

The same intimate understanding of emotions and interactions found in  Write It All Down: How to put your life on the page by Cathy Rentzenbrink [Jan. 6, Bluebird] I’ve read all of Rentzenbrink’s books, but the last few have been disappointing. Alas, this is more of a therapy session than a practical memoir-writing guide. (Full review coming later this month.)

Write It All Down: How to put your life on the page by Cathy Rentzenbrink [Jan. 6, Bluebird] I’ve read all of Rentzenbrink’s books, but the last few have been disappointing. Alas, this is more of a therapy session than a practical memoir-writing guide. (Full review coming later this month.)  Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence by Gavin Francis [Jan. 13, Wellcome Collection]: A short, timely book about the history and subjectivity of recovering from illness. (Full review and giveaway coming next week.)

Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence by Gavin Francis [Jan. 13, Wellcome Collection]: A short, timely book about the history and subjectivity of recovering from illness. (Full review and giveaway coming next week.)  The Store-House of Wonder and Astonishment by Sherry Rind [Jan. 15, Pleasure Boat Studio]: In her learned and mischievous fourth collection, the Seattle poet ponders Classical and medieval attitudes towards animals. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)

The Store-House of Wonder and Astonishment by Sherry Rind [Jan. 15, Pleasure Boat Studio]: In her learned and mischievous fourth collection, the Seattle poet ponders Classical and medieval attitudes towards animals. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)  Stepmotherland by Darrel Alejandro Holnes [Feb. 1, University of Notre Dame Press]: Holnes’s debut collection, winner of the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize, ponders a mixed-race background and queerness through art, current events and religion. Poems take a multitude of forms; the erotic and devotional mix in provocative ways. (See my full review at

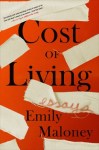

Stepmotherland by Darrel Alejandro Holnes [Feb. 1, University of Notre Dame Press]: Holnes’s debut collection, winner of the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize, ponders a mixed-race background and queerness through art, current events and religion. Poems take a multitude of forms; the erotic and devotional mix in provocative ways. (See my full review at  Cost of Living: Essays by Emily Maloney [Feb. 8, Henry Holt]: Probing mental illness and pain from the medical professional’s perspective as well as the patient’s, 16 autobiographical essays ponder the value of life. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)

Cost of Living: Essays by Emily Maloney [Feb. 8, Henry Holt]: Probing mental illness and pain from the medical professional’s perspective as well as the patient’s, 16 autobiographical essays ponder the value of life. (Full review coming to Shelf Awareness soon.)  Circle Way: A Daughter’s Memoir, a Writer’s Journey Home by Mary Ann Hogan [Feb. 15, Wonderwell]: A posthumous memoir of family and fate that focuses on a father-daughter pair of writers. A fourth-generation Californian, Hogan followed in her father Bill’s footsteps as a local journalist. Collage-like, the book features song lyrics and wordplay as well as family anecdotes. (See my full review at

Circle Way: A Daughter’s Memoir, a Writer’s Journey Home by Mary Ann Hogan [Feb. 15, Wonderwell]: A posthumous memoir of family and fate that focuses on a father-daughter pair of writers. A fourth-generation Californian, Hogan followed in her father Bill’s footsteps as a local journalist. Collage-like, the book features song lyrics and wordplay as well as family anecdotes. (See my full review at  Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au [Feb. 23, Fitzcarraldo Editions]: A delicate work of autofiction – it reads like a Chloe Aridjis or Rachel Cusk novel – about a woman and her Hong Kong-raised mother on a trip to Tokyo. (Full review coming up in a seasonal post.)

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au [Feb. 23, Fitzcarraldo Editions]: A delicate work of autofiction – it reads like a Chloe Aridjis or Rachel Cusk novel – about a woman and her Hong Kong-raised mother on a trip to Tokyo. (Full review coming up in a seasonal post.)  The Carriers: What the Fragile X Gene Reveals about Family, Heredity, and Scientific Discovery by Anne Skomorowsky [May 3, Columbia UP]: Blending stories and interviews with science and statistics, this balances the worldwide scope of a disease with its intimate details. (Full review coming to Foreword soon.)

The Carriers: What the Fragile X Gene Reveals about Family, Heredity, and Scientific Discovery by Anne Skomorowsky [May 3, Columbia UP]: Blending stories and interviews with science and statistics, this balances the worldwide scope of a disease with its intimate details. (Full review coming to Foreword soon.)  This Boy We Made: A Memoir of Motherhood, Genetics, and Facing the Unknown by Taylor Harris [Jan. 11, Catapult] (Reading via Edelweiss; to review for BookBrowse)

This Boy We Made: A Memoir of Motherhood, Genetics, and Facing the Unknown by Taylor Harris [Jan. 11, Catapult] (Reading via Edelweiss; to review for BookBrowse)

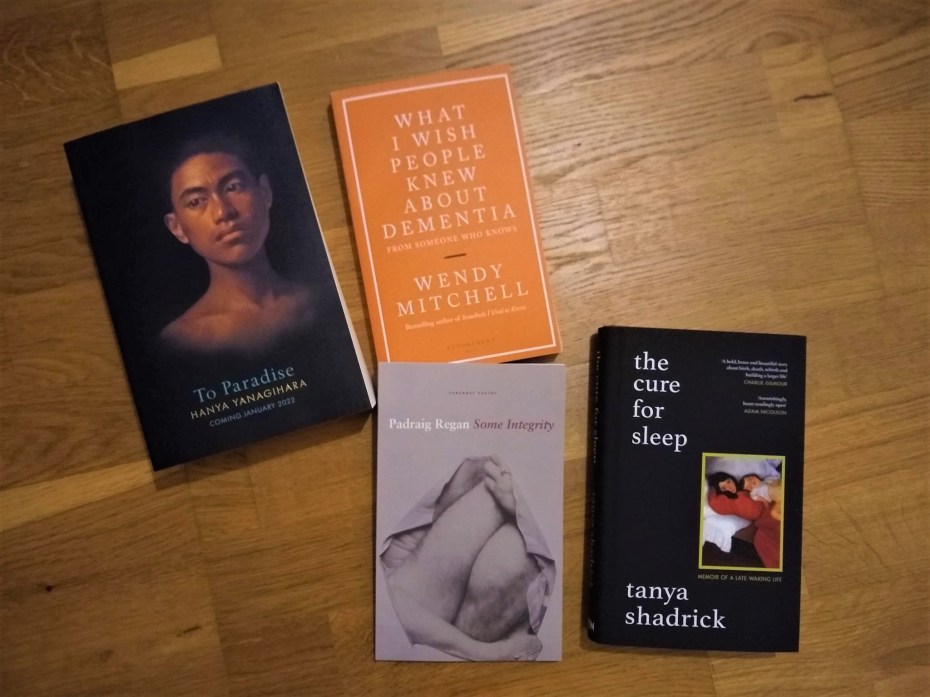

What I Wish People Knew About Dementia by Wendy Mitchell [Jan. 20, Bloomsbury]: “When Mitchell was diagnosed with young-onset dementia at the age of fifty-eight, her brain was overwhelmed with images of the last stages of the disease – those familiar tropes, shortcuts and clichés that we are fed by the media, or even our own health professionals. … Wise, practical and life affirming, [this] combines anecdotes, research and Mitchell’s own brilliant wit and wisdom to tell readers exactly what she wishes they knew about dementia.”

What I Wish People Knew About Dementia by Wendy Mitchell [Jan. 20, Bloomsbury]: “When Mitchell was diagnosed with young-onset dementia at the age of fifty-eight, her brain was overwhelmed with images of the last stages of the disease – those familiar tropes, shortcuts and clichés that we are fed by the media, or even our own health professionals. … Wise, practical and life affirming, [this] combines anecdotes, research and Mitchell’s own brilliant wit and wisdom to tell readers exactly what she wishes they knew about dementia.” I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins [Came out in USA last year; UK release = Jan. 20, Quercus]: “Leaving behind her husband and their baby daughter, a writer gets on a flight for a speaking engagement in Reno, not carrying much besides a breast pump and a spiraling case of postpartum depression. … Deep in the Mojave Desert where she grew up, she meets her ghosts at every turn: the first love whose self-destruction still haunts her; her father, a member of the most famous cult in American history.”

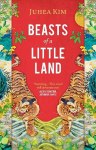

I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins [Came out in USA last year; UK release = Jan. 20, Quercus]: “Leaving behind her husband and their baby daughter, a writer gets on a flight for a speaking engagement in Reno, not carrying much besides a breast pump and a spiraling case of postpartum depression. … Deep in the Mojave Desert where she grew up, she meets her ghosts at every turn: the first love whose self-destruction still haunts her; her father, a member of the most famous cult in American history.” Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim [Feb. 3, Oneworld]: “From the perfumed chambers of a courtesan school in Pyongyang to the chic cafes of a modernising Seoul and the thick forests of Manchuria, Juhea Kim’s unforgettable characters forge their own destinies as they shape the future of their nation. Immersive and elegant, firmly rooted in Korean folklore and legend, [this] unveils a world where friends become enemies, enemies become saviours, and beasts take many shapes.”

Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim [Feb. 3, Oneworld]: “From the perfumed chambers of a courtesan school in Pyongyang to the chic cafes of a modernising Seoul and the thick forests of Manchuria, Juhea Kim’s unforgettable characters forge their own destinies as they shape the future of their nation. Immersive and elegant, firmly rooted in Korean folklore and legend, [this] unveils a world where friends become enemies, enemies become saviours, and beasts take many shapes.”

Theatre of Marvels by Lianne Dillsworth [April 28, Hutchinson Heinemann]: “Unruly crowds descend on Crillick’s Variety Theatre. Young actress Zillah [a mixed-race orphan] is headlining tonight. … Rising up the echelons of society is everything Zillah has ever dreamed of. But when a new stage act disappears, Zillah is haunted by a feeling that something is amiss. Is the woman in danger? Her pursuit of the truth takes her into the underbelly of the city.” (Unsolicited) [Dillsworth is Black British.]

Theatre of Marvels by Lianne Dillsworth [April 28, Hutchinson Heinemann]: “Unruly crowds descend on Crillick’s Variety Theatre. Young actress Zillah [a mixed-race orphan] is headlining tonight. … Rising up the echelons of society is everything Zillah has ever dreamed of. But when a new stage act disappears, Zillah is haunted by a feeling that something is amiss. Is the woman in danger? Her pursuit of the truth takes her into the underbelly of the city.” (Unsolicited) [Dillsworth is Black British.] The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw [Came out in USA in 2020; UK release = May 5, Pushkin]: “explores the raw and tender places where Black women and girls dare to follow their desires and pursue a momentary reprieve from being good. … With their secret longings, new love, and forbidden affairs, these church ladies are as seductive as they want to be, as vulnerable as they need to be, as unfaithful and unrepentant as they care to be, and as free as they deserve to be.”

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw [Came out in USA in 2020; UK release = May 5, Pushkin]: “explores the raw and tender places where Black women and girls dare to follow their desires and pursue a momentary reprieve from being good. … With their secret longings, new love, and forbidden affairs, these church ladies are as seductive as they want to be, as vulnerable as they need to be, as unfaithful and unrepentant as they care to be, and as free as they deserve to be.”

This year we can expect new fiction from Julian Barnes, Carol Birch, Jessie Burton, Jennifer Egan, Karen Joy Fowler, David Guterson, Sheila Heti, John Irving (perhaps? at last), Liza Klaussman, Benjamin Myers, Julie Otsuka, Alex Preston and Anne Tyler; a debut novel from Emilie Pine; second memoirs from Amy Liptrot and Wendy Mitchell; another wide-ranging cultural history/self-help book from Susan Cain; another medical history from Lindsey Fitzharris; a biography of the late Jan Morris; and much more. (Already I feel swamped, and this in a year when I’ve said I want to

This year we can expect new fiction from Julian Barnes, Carol Birch, Jessie Burton, Jennifer Egan, Karen Joy Fowler, David Guterson, Sheila Heti, John Irving (perhaps? at last), Liza Klaussman, Benjamin Myers, Julie Otsuka, Alex Preston and Anne Tyler; a debut novel from Emilie Pine; second memoirs from Amy Liptrot and Wendy Mitchell; another wide-ranging cultural history/self-help book from Susan Cain; another medical history from Lindsey Fitzharris; a biography of the late Jan Morris; and much more. (Already I feel swamped, and this in a year when I’ve said I want to  To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara [Jan. 11, Picador / Doubleday] You’ll see this on just about every list; her fans are legion after the wonder that was

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara [Jan. 11, Picador / Doubleday] You’ll see this on just about every list; her fans are legion after the wonder that was  How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu [Jan. 18, Bloomsbury / William Morrow] Amazing author name! Similar to the Yanagihara what with the century-hopping and future scenario, a feature common in 2020s literature – a throwback to Cloud Atlas? I’m also reminded of the premise of Under the Blue, one of my favourites from last year. “Once unleashed, the Arctic Plague will reshape life on Earth for generations to come.”

How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu [Jan. 18, Bloomsbury / William Morrow] Amazing author name! Similar to the Yanagihara what with the century-hopping and future scenario, a feature common in 2020s literature – a throwback to Cloud Atlas? I’m also reminded of the premise of Under the Blue, one of my favourites from last year. “Once unleashed, the Arctic Plague will reshape life on Earth for generations to come.” How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman [March 29, Scribner] I enjoyed her earlier story collection,

How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman [March 29, Scribner] I enjoyed her earlier story collection,  there are more things by Yara Rodrigues Fowler [April 28, Fleet] I so wanted her 2019 debut novel,

there are more things by Yara Rodrigues Fowler [April 28, Fleet] I so wanted her 2019 debut novel,

Search by Michelle Huneven [April 28, Penguin] A late addition to my list thanks to the

Search by Michelle Huneven [April 28, Penguin] A late addition to my list thanks to the

You Have a Friend in 10a: Stories by Maggie Shipstead [May 19, Transworld / May 17, Knopf] Shipstead’s Booker-shortlisted doorstopper, Great Circle, ironically, never took off for me; I’m hoping her short-form storytelling will work out better. “Diving into eclectic and vivid settings, from an Olympic village to a deathbed in Paris to a Pacific atoll, … Shipstead traverses ordinary and unusual realities with cunning, compassion, and wit.”

You Have a Friend in 10a: Stories by Maggie Shipstead [May 19, Transworld / May 17, Knopf] Shipstead’s Booker-shortlisted doorstopper, Great Circle, ironically, never took off for me; I’m hoping her short-form storytelling will work out better. “Diving into eclectic and vivid settings, from an Olympic village to a deathbed in Paris to a Pacific atoll, … Shipstead traverses ordinary and unusual realities with cunning, compassion, and wit.”

Horse by Geraldine Brooks [June 2, Little, Brown / June 14, Viking] You guessed it, another tripartite 1800s–1900s–2000s narrative! With themes of slavery, art and general African American history. I’m not big on horses, at least not these days, but Brooks’s

Horse by Geraldine Brooks [June 2, Little, Brown / June 14, Viking] You guessed it, another tripartite 1800s–1900s–2000s narrative! With themes of slavery, art and general African American history. I’m not big on horses, at least not these days, but Brooks’s

A Brief History of Living Forever by Jaroslav Kalfar [Aug. 4, Sceptre / Little, Brown] His

A Brief History of Living Forever by Jaroslav Kalfar [Aug. 4, Sceptre / Little, Brown] His  The Cure for Sleep by Tanya Shadrick [Jan. 20, Weidenfeld & Nicolson] Nature memoir / self-help. “On return from near-death, Shadrick vows to stop sleepwalking through life. … Around the care of young children, she starts to play with the shape and scale of her days: to stray from the path, get lost in the woods, make bargains with strangers … she moves beyond her respectable roles as worker, wife and mother in a small town.” [Review copy]

The Cure for Sleep by Tanya Shadrick [Jan. 20, Weidenfeld & Nicolson] Nature memoir / self-help. “On return from near-death, Shadrick vows to stop sleepwalking through life. … Around the care of young children, she starts to play with the shape and scale of her days: to stray from the path, get lost in the woods, make bargains with strangers … she moves beyond her respectable roles as worker, wife and mother in a small town.” [Review copy] The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness by Meghan O’Rourke [March 1, Riverhead] O’Rourke wrote

The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness by Meghan O’Rourke [March 1, Riverhead] O’Rourke wrote

Home/Land: A Memoir of Departure and Return by Rebecca Mead [April 21, Grove Press UK / Feb. 8, Knopf] I enjoyed Mead’s

Home/Land: A Memoir of Departure and Return by Rebecca Mead [April 21, Grove Press UK / Feb. 8, Knopf] I enjoyed Mead’s

Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble by Carolyn Oliver [Aug. 19, Univ. of Utah Press] Carolyn used to blog at

Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble by Carolyn Oliver [Aug. 19, Univ. of Utah Press] Carolyn used to blog at