Tag Archives: Alden Jones

The Best Books from the First Half of 2025

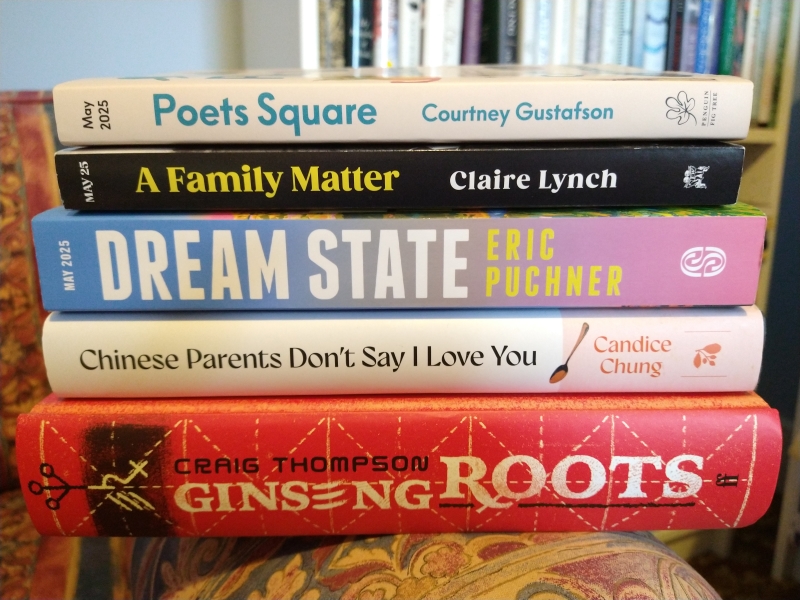

Hard to believe it, but it’s that time of year already. It’s the ninth year in a row that I’ve been making a first-half superlatives list. It remains to be seen how many of these will make it onto my overall best-of year rundown, but for now, these are my 16 favourite 2025 releases that I’ve read so far (representing the top ~21% of my current-year reading). Pictured below are the ones I read in print; all the others were e-copies. Links are to my full reviews.

Fiction

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel: Alison has writer’s block and is consumed with anxiety about the state of the world. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” Then she has an idea for a book – or maybe a reality TV series – called $UM that will wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored here. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close.

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel: Alison has writer’s block and is consumed with anxiety about the state of the world. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” Then she has an idea for a book – or maybe a reality TV series – called $UM that will wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored here. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Save Me, Stranger by Erika Krouse: Twelve first-person narratives voiced by people in crisis, for whom encounters with strangers tender the possibility of transformation. In the title story, the narrator is taken hostage in a convenience store hold-up. Others are set in Thailand and Japan as well as various U.S. states. Krouse focuses on young women presented with dilemmas and often eschews tidy endings, leaving characters on the brink and allowing readers to draw inferences. Fans of Danielle Evans and Lauren Groff have a treat in store.

Save Me, Stranger by Erika Krouse: Twelve first-person narratives voiced by people in crisis, for whom encounters with strangers tender the possibility of transformation. In the title story, the narrator is taken hostage in a convenience store hold-up. Others are set in Thailand and Japan as well as various U.S. states. Krouse focuses on young women presented with dilemmas and often eschews tidy endings, leaving characters on the brink and allowing readers to draw inferences. Fans of Danielle Evans and Lauren Groff have a treat in store.

Insectopolis: A Natural History by Peter Kuper: “If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” (E. O. Wilson) After an unspecified apocalypse, only insects remain. Group by group, they guide readers through an empty New York Public Library exhibit, interacting within and across species. It’s a sly blend of science, history, stories and silliness. There are interludes about insects in literature and unsung heroines of entomology. Informative and entertaining at once; what could be better? Welcome our insect overlords!

Insectopolis: A Natural History by Peter Kuper: “If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” (E. O. Wilson) After an unspecified apocalypse, only insects remain. Group by group, they guide readers through an empty New York Public Library exhibit, interacting within and across species. It’s a sly blend of science, history, stories and silliness. There are interludes about insects in literature and unsung heroines of entomology. Informative and entertaining at once; what could be better? Welcome our insect overlords!

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch: In her research into UK divorce cases in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, imagines such a situation through close portraits of three family members. Maggie knew only that her mother, Dawn, abandoned her when she was little. Lynch’s compassion is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch: In her research into UK divorce cases in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, imagines such a situation through close portraits of three family members. Maggie knew only that her mother, Dawn, abandoned her when she was little. Lynch’s compassion is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times.

Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund: Nine short fictions form a stunning investigation into how violence and family dysfunction reverberate. “The Peeping Toms” and “The Stalker” are a knockout pair featuring Albuquerque lesbian couples under threat by male acquaintances. Characters are haunted by loss and grapple with moral dilemmas. Each story has the complexity and emotional depth of a novel. Freedom versus safety for queer people is a resonant theme in an engrossing collection ideal for Alice Munro and Edward St. Aubyn fans.

Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund: Nine short fictions form a stunning investigation into how violence and family dysfunction reverberate. “The Peeping Toms” and “The Stalker” are a knockout pair featuring Albuquerque lesbian couples under threat by male acquaintances. Characters are haunted by loss and grapple with moral dilemmas. Each story has the complexity and emotional depth of a novel. Freedom versus safety for queer people is a resonant theme in an engrossing collection ideal for Alice Munro and Edward St. Aubyn fans.

Dream State by Eric Puchner: It starts as a glistening romantic comedy about t Charlie and Cece’s chaotic wedding at a Montana lake house in summer 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then the best man, Garrett, falls in love with the bride. The rest examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle as it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires. Still, there are funny set-pieces and warm family interactions. Cross Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

Dream State by Eric Puchner: It starts as a glistening romantic comedy about t Charlie and Cece’s chaotic wedding at a Montana lake house in summer 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then the best man, Garrett, falls in love with the bride. The rest examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle as it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires. Still, there are funny set-pieces and warm family interactions. Cross Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Nonfiction

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung: A vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. Chung reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” The essays range in time and style, delicately contrasting past and present, singleness and being partneredr.

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung: A vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. Chung reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” The essays range in time and style, delicately contrasting past and present, singleness and being partneredr.

Poets Square: A Memoir in 30 Cats by Courtney Gustafson: Working for a food bank, trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents: Gustafson saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for a feral cat colony in her Tucson, Arizona neighbourhood. With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is a cathartic memoir and a probing study of building communities of care in times of hardship.

Poets Square: A Memoir in 30 Cats by Courtney Gustafson: Working for a food bank, trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents: Gustafson saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for a feral cat colony in her Tucson, Arizona neighbourhood. With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is a cathartic memoir and a probing study of building communities of care in times of hardship.

Edge of the World: An Anthology of Queer Travel Writing, ed. Alden Jones: Sixteen authors of diverse sexual orientations and genders contrast here and there and then and now as they narrate sensory memories and personal epiphanies. In these pieces, time abroad sparks clarity. There’s power in queer solidarity, whether one is in Berlin or Key West. Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s piece is the highlight. A stellar anthology of miniature travelogues that are as illuminating about identity as they are about the places they feature.

Edge of the World: An Anthology of Queer Travel Writing, ed. Alden Jones: Sixteen authors of diverse sexual orientations and genders contrast here and there and then and now as they narrate sensory memories and personal epiphanies. In these pieces, time abroad sparks clarity. There’s power in queer solidarity, whether one is in Berlin or Key West. Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s piece is the highlight. A stellar anthology of miniature travelogues that are as illuminating about identity as they are about the places they feature.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham: An outstanding book-length essay that compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. This is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham: An outstanding book-length essay that compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. This is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.

Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything (Essays on the Future that Never Was) by Colette Shade: Shade’s debut collection contains 10 perceptive essays that contrast the promise and political pitfalls of “the Y2K Era” (1997–2008). The author recalls the thrill of early Internet use and celebrity culture. Consumerism was a fundamental doctrine but the financial crash prompted a loss of faith in progress. Outer space motifs, reality television, Smashmouth lyrics: it’s a feast of millennial nostalgia. Yet this hard-hitting work of cultural criticism, recommended to Jia Tolentino fans, reminisces only to burst bubbles.

Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything (Essays on the Future that Never Was) by Colette Shade: Shade’s debut collection contains 10 perceptive essays that contrast the promise and political pitfalls of “the Y2K Era” (1997–2008). The author recalls the thrill of early Internet use and celebrity culture. Consumerism was a fundamental doctrine but the financial crash prompted a loss of faith in progress. Outer space motifs, reality television, Smashmouth lyrics: it’s a feast of millennial nostalgia. Yet this hard-hitting work of cultural criticism, recommended to Jia Tolentino fans, reminisces only to burst bubbles.

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson: A book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with Thompson’s childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. As an adult, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation, lore, and medicinal uses. Roots are symbolic of a family story that unfolds in parallel. Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers.

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson: A book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with Thompson’s childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. As an adult, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation, lore, and medicinal uses. Roots are symbolic of a family story that unfolds in parallel. Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers.

Poetry

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler: This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques. It leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability. The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen. Monologues and sonnets recur. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance.

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler: This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques. It leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability. The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen. Monologues and sonnets recur. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine: McAlpine’s second collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes. She expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets; mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Just my sort of poetry: sweet on the ear, rooted in nature and the everyday.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine: McAlpine’s second collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes. She expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets; mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Just my sort of poetry: sweet on the ear, rooted in nature and the everyday.

Which of these grab your attention? What other 2025 releases should I catch up on?

Book Serendipity, Mid-February to Mid-April

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- The protagonist isn’t aware that they’re crying until someone tells them / they look in a mirror in The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro and Three Days in June by Anne Tyler.

- A residential complex with primal scream therapy in Confessions by Catherine Airey and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

- Memories of wiping down groceries during the early days of the pandemic in The End Is the Beginning by Jill Bialosky and Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly.

- A few weeks before I read Maurice and Maralyn by Sophie Elmhirst, I’d finished reading the author’s husband’s debut novel (Going Home by Tom Lamont); I had no idea of the connection between them until I got to her Acknowledgements.

- A mention of the same emergency money passing between friends in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez ($20) and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey ($100).

- Autobiographical discussions of religiosity and anorexia in The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey and Godstruck by Kelsey Osgood.

- The theme of the dark night sky in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, followed almost immediately by Night Magic by Leigh Ann Henion.

- Last year I learned about Marina Abramović’s performance art where she and her ex trekked to China’s Great Wall from different directions, met in the middle, and continued walking away to dramatize their breakup in The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton. Recently I saw it mentioned again in The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey. Abramović’s work is also mentioned in Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly and is the basis for the opening track on Anne-Marie Sanderson’s album Old Light, “Amethyst Shoes.”

- The idea of running towards danger appears in Alex Marzano-Lesnevich’s essay in Edge of the World, a queer travel anthology edited by Alden Jones; and the bibliography of The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

- I then read another Alex Marzano-Lesnevich essay in quick succession (both were excellent, by the way) in What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate.

- A scene in which a woman goes to a police station and her concerns are dismissed because she has no evidence and the man/men’s behaviour isn’t ‘bad enough’ in I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly.

- Too many details as the sign of a lie in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Three Days in June by Anne Tyler.

- Scenes of throwing all of a spouse’s belongings out on the yard/street in Old Soul by Susan Barker, How to Survive Your Mother by Jonathan Maitland, and Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly.

- Reading two lost American classics about motherhood and time spent in a mental institution at the same time: The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman and I Am Clarence by Elaine Kraf.

- Disorientation underwater: a literal experience in I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell, then used as a metaphor for what it was like to be stuck in a blizzard on Annapurna in 2014 in The Secret Life of Snow by Giles Whittell.

- A teenager who has a job cleaning hotels in Old Soul by Susan Barker and I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell. (In Stir-Fry by Emma Donoghue, Maria is also a teenaged cleaner, but of office buildings.)

- A vacuum cleaner bag splits in Stir-Fry by Emma Donoghue and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund – in the latter it’s deliberate, searching for evidence of the character’s late son after cleaning his room.

- An ailing tree or trees that have to be cut down in one story of The Accidentals by Guadalupe Nettel and The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue by Mike Tidwell.

- Buchenwald was mentioned in one poem each in A God at the Door by Tishani Doshi and The Ghost Orchid by Michael Longley.

- A reference to Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass in To Have or to Hold by Sophie Pavelle and Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly.

- A mentally unwell woman deliberately burns her hands in I Am Clarence by Elaine Kraf and Every Day Is Mother’s Day by Hilary Mantel.

- A mention of the pollution caused by gas stoves in We Do Not Part by Han Kang and The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue by Mike Tidwell.

- An art installation involving part-buried trees was mentioned in Immemorial by Lauren Markham and then I encountered a similar project a few months later in We Do Not Part by Han Kang. Burying trees as a method of carbon storage is then discussed in The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue by Mike Tidwell.

- Imagining the lives of the people living in an apartment you didn’t end up renting in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and one story of The Accidentals by Guadalupe Nettel.

- The Anthropocene is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and The Alternatives by Caoilinn Hughes.

- I was reading three debut novels from the McKitterick Prize longlist at the same time, all of them with very similar page counts of 383, 387, and 389 (i.e., too long!).

- Being appalled at an institutionalized mother’s appearance in The End Is the Beginning by Jill Bialosky and Every Day Is Mother’s Day by Hilary Mantel.

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

- A lesbian couple in New Mexico, the experience of being watched through a window, and the mention of a caftan/kaftan, in Old Soul by Susan Barker and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Refusal to go to a hospital despite being in critical condition in I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- It’s not a niche stylistic decision anymore; I was reading four novels with no speech marks at the same time: Old Soul by Susan Barker, Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin, The Alternatives by Caoilinn Hughes, and We Do Not Part by Han Kang. [And then, a bit later, three more: Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz, Mouthing by Orla Mackey, and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.]

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

A lesbian couple is alarmed by the one partner’s family keeping guns in Spent by Alison Bechdel and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Responding to the 2021 murder of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in Foreign Fruit by Katie Goh and Find Me as the Creature I Am by Emily Jungmin Yoon.

- Disposing of a late father’s soiled mattress in Mouthing by Orla Mackey and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A Jewish care home for the elderly in The End Is the Beginning by Jill Bialosky and Joanna Rakoff’s essay in What My Father and I Don’t Talk About (ed. Michele Filgate).

- A woman has no memory between leaving a bar and first hooking up with the man she’s having an affair with in If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

- A pygmy goat as a pet (and a one-syllable, five-letter S title!) in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A Brooklyn setting and thirtysomething female protagonist in Sleep by Honor Jones, So Happy for You by Celia Laskey, and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A mention of the American Girl historical dolls franchise in Sleep by Honor Jones and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard, both of which I’m reviewing early for Shelf Awareness.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

- The protagonist’s therapist asks her to find more precise words for her feelings in Blue Hour by Tiffany Clarke Harrison and So Happy for You by Celia Laskey.

- The protagonist “talks” with a dying dog or cat in The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

- The Rapunzel fairytale is a point of reference in In the Evening, We’ll Dance by Anne-Marie Erickson and Secret Agent Man by Margot Singer, both of which I was reading early for Foreword Reviews.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Book Serendipity, Mid-December 2024 to Mid-February 2025

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- The angel Ariel appears in Through a Glass Darkly by Jostein Gaarder and Constructing a Witch by Helen Ivory.

- The protagonist’s surname is English in Wild Houses by Colin Barrett and The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn.

- I read scenes of grief over a tree being cut down / falling next to one’s house in Dispersals by Jessica J. Lee and Small Rain by Garth Greenwell, one right after the other.

- A mother who does kundalini yoga in All Fours by Miranda July and Unattached by Reannon Muth.

- The idea that happiness (unlike anxiety and sorrow) leaves no trace in writing or in life appeared for me on the same day in Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks and Small Rain by Garth Greenwell.

- Someone considers suicide by falling but realizes that at the current height they would injure themself but not die in Wild Houses by Colin Barrett, The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham, and The Courage Consort by Michel Faber.

- The homosexual “bear” stereotype appears in The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham and Small Rain by Garth Greenwell.

- A William Blake epigraph in Open, Heaven by Seán Hewitt and one of the poems included in Poetry Unbound by Pádraig Ó Tuama.

- A group biography including nine pen portraits (plus the author): Nine Minds by Daniel Tammet, followed in quick succession by Uneven by Sam Mills. (Similar, but with just seven subjects, is a book I’m currently reading about women’s religious conversions, Godstruck by Kelsey Osgood.)

- A book–life serendipity moment: in All Fours by Miranda July there is mention of an elderly cat named Alfie who needs to be given medication several times a day. Snap!

- By chance, I started reading Myself and Other Animals, a posthumous collection of short autobiographical pieces by Gerald Durrell, on his centenary (7 January 2025).

- Guilt over destroying a bird’s nest in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

- The main female character has a birthmark in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt.

- Reading two novels at the same time that open with a new family having to be found for a little boy because his mentally ill mother is presumed to have died by suicide: Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

The protagonist is mistaken for a two-year-old boy’s father in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

- The mother is named Ellen in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

- An ailing elderly father named Vic in Going Home by Tom Lamont and The God of the Woods by Liz Moore.

- A mother is sent to a mental hospital after the loss of her young son in Invisible by Paul Auster and The God of the Woods by Liz Moore.

- A brother and sister share a New York City apartment in Invisible by Paul Auster and The Book of George by Kate Greathead.

- A mention of the Japanese artist Hokusai in While the Earth Holds Its Breath by Helen Moat and The Secret Life of Snow by Giles Whittell.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

Adults dressing up for Halloween in The Blindfold by Siri Hustvedt and I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman.

- A second husband named Tim in Unexpected Lessons in Love by Bernardine Bishop and Because We Must by Tracy Youngblom.

- The idea that ‘queers find each other’ in Edge of the World: An Anthology of Queer Travel Writing edited by Alden Jones and My Autobiography of Carson McCullers by Jenn Shapland.

- Experiencing 9/11 as a freshman in college (just like me!) in Dirty Kitchen by Jill Damatac and The Book of George by Kate Greathead. (There is also a 9/11 section in Confessions by Catherine Airey.)

- An intense poker game in I’ll Come to You by Rebecca Kauffman and Going Home by Tom Lamont.

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

The main character is expelled on false drug possession charges in Invisible by Paul Auster and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

- Missing the chance to say goodbye before a father’s death, and a parent wondering aloud to their son whether they’ve been a good parent in The Book of George by Kate Greathead and The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro.

- Someone departs suddenly, leaving her clothes and books behind, in Invisible by Paul Auster and My Autobiography of Carson McCullers by Jenn Shapland.

- Mentions of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, an Obama-era U.S. immigration policy) and “Two-Buck Chuck” (a nickname for the Charles Shaw bargain wine sold at Trader Joe’s) in Dirty Kitchen by Jill Damatac and Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez.

- A City Hall wedding in New York City in Baumgartner by Paul Auster and Dirty Kitchen by Jill Damatac.

- Polish Jewish heritage and a parent who died of pancreatic cancer in Baumgartner by Paul Auster and The History of Love by Nicole Krauss.

- In Because We Must by Tracy Youngblom, she reads The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo aloud to her son while he is recovering in hospital. I was reading Despereaux at the same time! (Also, in real-life serendipity, Youngblom and I both have a sister named Trish.)

- A code of 1–3 knocks is used in Confessions by Catherine Airey and The History of Love by Nicole Krauss.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

A scene of a teacup breaking in Junction of Earth and Sky by Susan Buttenwieser and The Möbius Book by Catherine Lacey.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

August Releases: Fiction Advocate, Kingsolver Poetry, Sarah Moss & More

My five new releases for August include two critical responses to contemporary classics; two poetry books, one a debut collection from Carcanet Press and the other by an author better known for fiction; and a circadian novel by one of my favorite authors.

I start with two of the latest releases from Fiction Advocate’s “Afterwords” series. The tagline is “Essential Readings of the New Canon,” and the idea is that “acclaimed writers investigate the contemporary classics.” (I reviewed the monographs on Blood Meridian, Fun Home, and The Year of Magical Thinking in this post.)

Dear Knausgaard: Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle by Kim Adrian

Karl Ove Knausgaard turned his pretty ordinary life into thousands of pages of autofiction that many readers have found addictive. Adrian valiantly grapples with his six-volume exploration of identity, examining the treatment of time and the dichotomies of intellect versus emotions, self versus other, and life versus fiction. She marvels at the ego that could sustain such a project, and at the seemingly rude decision to use all real names (whereas in her own family memoir she assigned aliases to most major figures). At many points she finds the character of “Karl Ove” insufferable, especially when he’s a teenager in Book 4, and the books’ prose dull. Knausgaard’s focus on male novelists and his stereotypical treatment of feminine qualities, here and in his other work, frequently madden her.

Karl Ove Knausgaard turned his pretty ordinary life into thousands of pages of autofiction that many readers have found addictive. Adrian valiantly grapples with his six-volume exploration of identity, examining the treatment of time and the dichotomies of intellect versus emotions, self versus other, and life versus fiction. She marvels at the ego that could sustain such a project, and at the seemingly rude decision to use all real names (whereas in her own family memoir she assigned aliases to most major figures). At many points she finds the character of “Karl Ove” insufferable, especially when he’s a teenager in Book 4, and the books’ prose dull. Knausgaard’s focus on male novelists and his stereotypical treatment of feminine qualities, here and in his other work, frequently madden her.

So why is My Struggle compelling nonetheless? It occupies her mind and her conversations for years. Is it something about the way that Knausgaard extracts meaning from seemingly inconsequential details? About how he stretches and compresses time in a Proustian manner to create a personal highlights reel? She frames her ambivalent musings as a series of letters written as if to Knausgaard himself (or “KOK,” as she affectionately dubs him) between February and September 2019. Cleverly, she mimics his style in both the critical enquiry and the glimpses into her own life, including all its minutiae – the weather, daily encounters, what she sees out the window and what she thinks about it all. It’s bold, playful and funny, and, all told, I enjoyed it more than Knausgaard’s own writing.

(I myself have only read Book 1, A Death in the Family, and wasn’t planning on continuing with My Struggle, but I think I will make an exception for Book 3 because of my recent fascination with childhood memoirs. I had better luck with Knausgaard’s Seasons Quartet, of which I’ve read all but Spring. I’ve reviewed Summer and Winter.)

My rating:

My thanks to Fiction Advocate for the free e-copy for review.

The Wanting Was a Wilderness: Cheryl Strayed’s Wild and the Art of Memoir by Alden Jones

Hiking is boring, yet Cheryl Strayed turned it into a beloved memoir. Jones explores how Wild works: how Strayed the author creates “Cheryl,” likeable despite her drug use and promiscuity; how the fixation on the boots and the backpack that carry her through her quest reflect the obsession over the loss of her mother; how the flashbacks break up the narrative and keep you guessing about whether she’ll reach her literal and emotional destinations.

Jones also considers the precedents of wilderness literature and the 1990s memoir boom that paved the way for Wild. I most enjoyed this middle section, which, like Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, surveys some of the key publications from a burgeoning genre. Another key point of reference is Vivian Gornick, who draws a distinction between “the situation” (the particulars or context) and “the story” (the message) – sometimes the map or message comes first, and sometimes you only discover it as you go along.

Jones also considers the precedents of wilderness literature and the 1990s memoir boom that paved the way for Wild. I most enjoyed this middle section, which, like Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, surveys some of the key publications from a burgeoning genre. Another key point of reference is Vivian Gornick, who draws a distinction between “the situation” (the particulars or context) and “the story” (the message) – sometimes the map or message comes first, and sometimes you only discover it as you go along.

I was a bit less interested in Jones’s reminiscences of her own three-month wilderness experience during college, when, with Outward Bound, she went to North Carolina and Mexico and hiked part of the Appalachian Trail and a volcano. This was the trip on which she faced up to her sexuality and had a short-lived relationship with a fellow camper, Melissa. But working out that she was bisexual and marrying a woman were both, as presented here, false endings. The real ending was her decision to leave her marriage – even though they had three children; even though the relationship was often fine. She attributes her courage to go, believing something better was possible, to Strayed’s work. And that’s the point of this series: rereading a contemporary classic until it becomes part of your own story.

My rating:

My thanks to Fiction Advocate for the free e-copy for review.

Two poetry releases:

Growlery by Katherine Horrex

As in Red Gloves by Rebecca Watts, released by Carcanet in June, I noted the juxtaposition of natural and industrial scenes. Horrex’s “Four Muses” include a power plant and a steelworks, and she writes about pottery workers and the Manchester area, but she also explores Goat Fell on foot. Two of my favorite poems were nature-based: “Omen,” about corpse flowers, and “Wood Frog.” Alliteration, metaphors and smells are particularly effective in the former. Though I quailed at the sight of an entry called “Brexit,” it’s a subtle offering that depicts mistrust and closed minds – “People personable as tents zipped shut”. By contrast, “House of Other Tongues” revels in the variety of languages and foods in an international student dorm. A few poems circle around fertility and pregnancy. The linking themes aren’t very strong across the book, but there are a few gems.

As in Red Gloves by Rebecca Watts, released by Carcanet in June, I noted the juxtaposition of natural and industrial scenes. Horrex’s “Four Muses” include a power plant and a steelworks, and she writes about pottery workers and the Manchester area, but she also explores Goat Fell on foot. Two of my favorite poems were nature-based: “Omen,” about corpse flowers, and “Wood Frog.” Alliteration, metaphors and smells are particularly effective in the former. Though I quailed at the sight of an entry called “Brexit,” it’s a subtle offering that depicts mistrust and closed minds – “People personable as tents zipped shut”. By contrast, “House of Other Tongues” revels in the variety of languages and foods in an international student dorm. A few poems circle around fertility and pregnancy. The linking themes aren’t very strong across the book, but there are a few gems.

My rating:

My thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

How to Fly (in Ten Thousand Easy Lessons) by Barbara Kingsolver

Kingsolver may not be well known for her poetry, but this is actually her second collection of verse after the bilingual Another America/Otra America (1992). The opening segment, “How to Fly,” is full of folk wisdom from nature and the body’s intuitive knowledge. “Pellegrinaggio” is a set of travel poems about accompanying her Italian mother-in-law back to her homeland. “This Is How They Come Back to Us” is composed of elegies for the family’s dead; four shorter remaining sections are inspired by knitting, literature, daily life, and concern for the environment. As with The Undying by Michel Faber, the book’s themes are stronger than its poetic techniques, but Kingsolver builds striking natural imagery and entrancing rhythms.

Kingsolver may not be well known for her poetry, but this is actually her second collection of verse after the bilingual Another America/Otra America (1992). The opening segment, “How to Fly,” is full of folk wisdom from nature and the body’s intuitive knowledge. “Pellegrinaggio” is a set of travel poems about accompanying her Italian mother-in-law back to her homeland. “This Is How They Come Back to Us” is composed of elegies for the family’s dead; four shorter remaining sections are inspired by knitting, literature, daily life, and concern for the environment. As with The Undying by Michel Faber, the book’s themes are stronger than its poetic techniques, but Kingsolver builds striking natural imagery and entrancing rhythms.

Two favorite passages to whet your appetite:

How to drink water when there is wine— / Once I knew all these brick-shaped things, / took them for the currency of survival. / Now I have lived long and I know better.

Tiptoe past the dogs of the apocalypse / asleep in the shade of your future. / Pay at the window. You’ll be surprised: you / can pass off hope like a bad check. You still / have time, that’s the thing. To make it good.

(To be reviewed in full, in conjunction with other recent/upcoming poetry releases, including Dearly by Margaret Atwood, for Shiny New Books.)

My rating:

I read an advanced e-copy via Edelweiss. (I’m unsure of the line breaks above because of the formatting.)

And finally, a much-anticipated release – bonus points for it having “Summer” in the title!

Summerwater by Sarah Moss

This is nearly as compact as Moss’s previous novella, Ghost Wall, yet contains a riot of voices. Set on one long day at a Scottish holiday park, it moves between the minds of 12 vacationers disappointed by the constant rain – “not that you come to Scotland expecting sun but this is a really a bit much, day after day of it, torrential” – and fed up with the loud music and partying that’s come from the Eastern Europeans’ chalet several nights this week. In the wake of Brexit, the casual xenophobia espoused by several characters is not surprising, but still sobering, and paves the way for a climactic finale that was not what I expected after some heavy foreshadowing involving a teenage girl going off to the pub through the woods.

The day starts at 5 a.m. with Justine going for a run, despite a recent heart health scare, and spends time with retirees, an engaged couple spending most of their time in bed, a 16-year-old kayaker, a woman with dementia, and more. We see different aspects of family dynamics as we revisit a previous character’s child, spouse or sibling. I had to laugh at Milly picturing Don Draper during sex with Josh, and at Claire getting an hour to herself without the kids and having no idea what to do with it beyond clean up and make a cup of tea. Moss gets each stream-of-consciousness internal monologue just right, from a frantic mum to a sarcastic teen.

The day starts at 5 a.m. with Justine going for a run, despite a recent heart health scare, and spends time with retirees, an engaged couple spending most of their time in bed, a 16-year-old kayaker, a woman with dementia, and more. We see different aspects of family dynamics as we revisit a previous character’s child, spouse or sibling. I had to laugh at Milly picturing Don Draper during sex with Josh, and at Claire getting an hour to herself without the kids and having no idea what to do with it beyond clean up and make a cup of tea. Moss gets each stream-of-consciousness internal monologue just right, from a frantic mum to a sarcastic teen.

Yet I had to wonder what it all added up to; this feels like a creative writing student exercise, with the ending not worth waiting for. Cosmic/nature interludes are pretentious à la Reservoir 13. It’s not the first time this year that I’ve been disappointed by the latest from a favorite author (see also Hamnet). But my previous advice stands: If you haven’t read Sarah Moss, do so immediately.

My rating:

My thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.