Tag Archives: Alessandro Baricco

The Woman in Black, Train Dreams, and Absolutely & Forever (#NovNov23)

I’ve been slow off the mark this year, mostly because instead of reading a sensible one or two novellas at a time, I’ve had 10 or 15 on the go. It might mean I’ll read more overall, but from day to day it feels like crawling through loads of books, never to finish any. Except I did finally finish these three, all of which were great reads. After my thoughts on each, I’ll ponder this week’s prompt, “What Is a Novella?”

The Woman in Black by Susan Hill (1983)

This was a reread for me and our November book club book, as well as part of my casual project to read books from my birth year. I’ve generally been underwhelmed by Hill’s ghost stories, but I found this spookier than remembered and enjoyed spotting the nods to Victorian literature and to classic ghost story tropes. (Best of all, because it was so short, everyone actually read the book and came to the discussion. All 12 group members. I can’t recall the last time that happened!)

Hill keeps the setting deliberately vague, but it seems that it might be the Lincolnshire Fens in the 1930s or so. Arthur Kipps is a young lawyer tasked with attending the funeral of old Mrs Drablow and sorting through her papers. Locals don’t envy him the time spent in Eel Marsh House, and when he starts seeing a wasting-away, smallpox-pocked woman dressed in black in the churchyard, he understands why. This place harbours a malevolent ghost, and from the empty nursery with its creaking rocking chair to the marsh’s treacherous mud, Arthur fears that it’s out to get him.

Hill keeps the setting deliberately vague, but it seems that it might be the Lincolnshire Fens in the 1930s or so. Arthur Kipps is a young lawyer tasked with attending the funeral of old Mrs Drablow and sorting through her papers. Locals don’t envy him the time spent in Eel Marsh House, and when he starts seeing a wasting-away, smallpox-pocked woman dressed in black in the churchyard, he understands why. This place harbours a malevolent ghost, and from the empty nursery with its creaking rocking chair to the marsh’s treacherous mud, Arthur fears that it’s out to get him.

The rational male narrator who insists he doesn’t believe in ghosts until he can’t deny an experience of one is a feature of the traditional ghost story à la M.R. James – and indeed, one of the chapter titles here (“Whistle and I’ll Come to You”) is a direct adaptation of a James story title. A framing story has Kipps as an older man writing the ghost story to share with his stepchildren. Some secondary characters have Dickensian names and there’s a Bleak House-esque description of a thick fog. The novel’s title must be an homage to Wilkie Collins’s sensation novel The Woman in White, with which it shares the theme of debated parentage.

A few members of our book club had seen the play or one of two film versions. Curiously, it seems like both movies alter the ending. Why, when the last four pages are such a perfect kicker? I might have dismissed the whole as a bit dull were it not for the brilliant conclusion. (Public library) [160 pages]

Train Dreams by Denis Johnson (2002)

This is Cathy’s example of a perfect novella. I picked it up on her recommendation and read it within a few days (though you could easily do so in one sitting). Robert Grainier is a manual labourer in the American West. His body shattered by logging before he turns 40 and his spirit nearly broken by the loss of his home to a forest fire, he looks for meaning in the tragedy and a purpose to the rest of his long life. Is he being punished for participating in the attempted lynching of a Chinese worker decried as a thief? Or for not helping an injured man he came across in the woods as a teenager?

Although Grainier might appear to be a Job-like figure, his loneliness never shades into despair, lightened by comic dialogues and the mildest of supernatural interventions. He starts a haulage business and keeps dogs. There are rumours of a wolf-girl in the area, and, convinced that his dog’s new pups are part-wolf, he teaches them to howl – his own favourite way of letting off steam.

Although Grainier might appear to be a Job-like figure, his loneliness never shades into despair, lightened by comic dialogues and the mildest of supernatural interventions. He starts a haulage business and keeps dogs. There are rumours of a wolf-girl in the area, and, convinced that his dog’s new pups are part-wolf, he teaches them to howl – his own favourite way of letting off steam.

A couple of gratuitously bleak scenes (a confession of incest and an accidental death) made me think Cormac McCarthy would be a major influence, but the tone is lighter than that. Richard Brautigan came to mind, and I imagine many contemporary writers have found inspiration here: Carys Davies, Ash Davidson, Donald Ray Pollock, even Patrick deWitt.

Gritty yet light, this presents life as an arbitrary accumulation of error and incident, longing (“Pulchritude!”) and effort. Grainier is an effective Everyman, such that his story feels not just all-American but universal. (Free from a neighbour) [116 pages]

Absolutely and Forever by Rose Tremain (2023)

I had lost track of Tremain’s career a bit; I find her work hit and miss – perhaps too varied, though judging by her last five novels, she seems to have settled on historical fiction as her wheelhouse. I wasn’t sure what to expect from this latest book, but seeing that it was novella length, I was willing to give it a try. Tremain follows her heroine, Marianne Clifford, from the 1950s up to perhaps 1970. At age 15, she falls hopelessly in love with an 18-year-old aspiring writer, Simon Hurst, and loses her virginity in the back of his pale blue Morris Minor. She feels grown-up and sophisticated, and imagines their romance as a grand adventure that will whisk her away from her parents’ stultifying ordinariness –

when I thought about my future as Mrs Simon Hurst (riding a camel in Egypt, floating along in a gondola in Venice, driving through the Grand Canyon in an open-topped Cadillac, watching elephants drink from a waterhole in Africa) and about Mummy’s future (in the red-brick house in Berkshire with the shivery birch tree and the two white columns, playing Scrabble with Daddy and shopping at Bartlett’s of Newbury), I could see that my life was going to be more interesting than hers and that she might already be envious

– but his new post-school life in Paris doesn’t have room for her. As she moves to London and trains for secretarial work, Marianne is bolstered by friendships with plain-speaking Scot Petronella (“Pet”) and Hugo Forster-Pellisier, her surfing and ping-pong partner on their parents’ Cornwall getaways. Forasmuch as her life changes over the next 15 years or so – taking on a traditional wife and homemaker role; her parents quietly declining – her attachment to her first love never falters.

– but his new post-school life in Paris doesn’t have room for her. As she moves to London and trains for secretarial work, Marianne is bolstered by friendships with plain-speaking Scot Petronella (“Pet”) and Hugo Forster-Pellisier, her surfing and ping-pong partner on their parents’ Cornwall getaways. Forasmuch as her life changes over the next 15 years or so – taking on a traditional wife and homemaker role; her parents quietly declining – her attachment to her first love never falters.

This has the chic and convincing 1960s setting of Tessa Hadley’s work. Marianne’s narration is a delight, droll but not as blasé as she tries to appear. Tremain could have easily fallen into the trap of making her purely naïve (in the moment) or nostalgic (looking back), but instead she’s rendered her voice knowing yet compassionate, and made her a real wit (“I thought, Everything in Paris looks as if it’s practising the waltz, whereas quite a lot of things in London … appear as if they’ve just come out of hospital after a leg operation”). Pet is very funny, too. And it’s always fun for me to have nearby locations: Newbury, Reading, Marlborough. In imagining a different life for herself, Marianne resists repeating her mother’s mistakes and coincides with the rising feminist movement. There are two characters named Marianne, and two named Simon; the revelations about these doubles are breathtaking.

This really put me through an emotional wringer. It’s no cheap tear-jerker but a tender depiction of love in all its forms. I think, with Academy Street by Mary Costello, it may be my near-perfect novella. (Public library) [181 pages]

Novellas in November, Week 2: What Is a Novella?

- Ponder the definition, list favourites, or choose ones you think best capture the ‘spirit’ of a novella.

A novella is defined by its length in words, but because that’s often difficult for readers to gauge, for this challenge we go by the number of pages instead, making 200 an absolute maximum – though some books with wide margins and spacing may top that but still seem slight enough to count (while those with tiny type can feel much longer than 160–200 pages).

Thematically, a novella is said to be concentrated on one character or small set of characters, with one plotline rather than several. This week I’ve been musing on a theory: a novella is to a novel what a memoir is to an autobiography. That is, if the latter is a comprehensive and often chronological story, the former focuses on a particular time or experience and shapes a narrative around it. What it potentially sacrifices in scope it makes up for with intensity.

But as soon as I’d formulated this hypothesis to myself, I started thinking of exceptions on either side. Train Dreams, like Silk by Alessandro Baricco and A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler, conveys a pretty complete life story. And no doubt there are many full-length novels that are almost claustrophobic in their adherence to one point of view and timeline.

The simplest way I’d put it is that a novella is a book that doesn’t outstay its welcome. I think it must be easier to write a doorstopper than a novella. Once you’ve arrived at a voice and a style, just keeping going can become a question of habit. But to continue paring back to get at the essence of a character and a situation – that takes real discipline. My other criterion would be that it has to portray the full range of human emotion, even if within a limited set of circumstances. Based on that, Train Dreams and Absolutely and Forever both triumph.

A few classic novellas that do this particularly well (links to my reviews):

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin

A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr

Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton

A few more contemporary novellas that do this particularly well (links to my reviews):

A Lie Someone Told You about Yourself by Peter Ho Davies

Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf

Foster by Claire Keegan

A Feather on the Breath of God by Sigrid Nunez

This Year’s “Snow” and “Winter” Reads

Longtime readers will know how much I enjoy reading with the seasons. Although it’s just starting to feel like there’s a promise of spring here in the south of England, I understand that much of North America is still cold and snowy, so I hope these recent reads of mine will feel topical to some of you – and the rest of you might store some ideas away for next winter.

(The Way Past Winter has already gone back to the library.)

Silence in the Snowy Fields and Other Poems by Robert Bly (1967)

Even when they’re in stanza form, these don’t necessarily read like poems; they’re often more like declaratory sentences, with the occasional out-of-place exclamation. But Bly’s eye is sharp as he describes the signs of the seasons, the sights and atmosphere of places he visits or passes through on the train (Ohio and Maryland get poems; his home state of Minnesota gets a whole section), and the small epiphanies of everyday life, whether alone or with friends. And the occasional short stanza hits like a wisdom-filled haiku, such as “There are palaces, boats, silence among white buildings, / Iced drinks on marble tops among cool rooms; / It is good also to be poor, and listen to the wind” (from “Poem against the British”).

Even when they’re in stanza form, these don’t necessarily read like poems; they’re often more like declaratory sentences, with the occasional out-of-place exclamation. But Bly’s eye is sharp as he describes the signs of the seasons, the sights and atmosphere of places he visits or passes through on the train (Ohio and Maryland get poems; his home state of Minnesota gets a whole section), and the small epiphanies of everyday life, whether alone or with friends. And the occasional short stanza hits like a wisdom-filled haiku, such as “There are palaces, boats, silence among white buildings, / Iced drinks on marble tops among cool rooms; / It is good also to be poor, and listen to the wind” (from “Poem against the British”).

Favorite wintry passages:

How strange to think of giving up all ambition!

Suddenly I see with such clear eyes

The white flake of snow

That has just fallen in the horse’s mane!

(“Watering the Horse” in its entirety)

The grass is half-covered with snow.

It was the sort of snowfall that starts in late afternoon,

And now the little houses of the grass are growing dark.

(the first stanza of “Snowfall in the Afternoon”)

My rating:

Wishing for Snow: A Memoir by Minrose Gwin (2004)

One of the more inventive and surprising memoirs I’ve read. Growing up in Mississippi in the 1920s–30s, Gwin’s mother wanted nothing more than for it to snow. That wistfulness, a nostalgia tinged with bitterness, pervades the whole book. By the time her mother, Erin Clayton Pitner, a published though never particularly successful poet, died of ovarian cancer in the late 1980s, their relationship was a shambles. Erin’s mental health was shakier than ever – she stole flowers from the church altar, frequently ran her car off the road, and lived off canned green beans – and she never forgave Minrose for having had her committed to a mental hospital. Poring over Erin’s childhood diaries and adulthood vocabulary notebook, photographs, the letters and cards that passed between them, remembered and imagined conversations and monologues, and Erin’s darkly observant unrhyming poems (“No place to hide / from the leer of the sun / searching out every pothole, / every dream denied”), Gwin asks of her late mother, “When did you reach the point that everything was in pieces?”

One of the more inventive and surprising memoirs I’ve read. Growing up in Mississippi in the 1920s–30s, Gwin’s mother wanted nothing more than for it to snow. That wistfulness, a nostalgia tinged with bitterness, pervades the whole book. By the time her mother, Erin Clayton Pitner, a published though never particularly successful poet, died of ovarian cancer in the late 1980s, their relationship was a shambles. Erin’s mental health was shakier than ever – she stole flowers from the church altar, frequently ran her car off the road, and lived off canned green beans – and she never forgave Minrose for having had her committed to a mental hospital. Poring over Erin’s childhood diaries and adulthood vocabulary notebook, photographs, the letters and cards that passed between them, remembered and imagined conversations and monologues, and Erin’s darkly observant unrhyming poems (“No place to hide / from the leer of the sun / searching out every pothole, / every dream denied”), Gwin asks of her late mother, “When did you reach the point that everything was in pieces?”

My rating:

The Way Past Winter by Kiran Millwood Hargrave (2018)

It has been winter for five years, and Sanna, Mila and Pípa are left alone in their little house in the forest – with nothing but cabbages to eat – when their brother Oskar is lured away by the same evil force that took their father years ago and has been keeping spring from coming. Mila, the brave middle daughter, sets out on a quest to rescue Oskar and the village’s other lost boys and to find the way past winter. Clearly inspired by the Chronicles of Narnia and especially Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy, this middle grade novel is set in an evocative, if slightly vague, Russo-Finnish past and has more than a touch of the fairy tale about it. I enjoyed it well enough, but wouldn’t seek out anything else by the author.

It has been winter for five years, and Sanna, Mila and Pípa are left alone in their little house in the forest – with nothing but cabbages to eat – when their brother Oskar is lured away by the same evil force that took their father years ago and has been keeping spring from coming. Mila, the brave middle daughter, sets out on a quest to rescue Oskar and the village’s other lost boys and to find the way past winter. Clearly inspired by the Chronicles of Narnia and especially Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy, this middle grade novel is set in an evocative, if slightly vague, Russo-Finnish past and has more than a touch of the fairy tale about it. I enjoyed it well enough, but wouldn’t seek out anything else by the author.

Favorite wintry passage:

“It was a winter they would tell tales about. A winter that arrived so sudden and sharp it stuck birds to branches, and caught the rivers in such a frost their spray froze and scattered down like clouded crystals on the stilled water. A winter that came, and never left.”

My rating:

Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata (1937; English translation, 1956)

[Translated from the Japanese by Edward G. Seidensticker]

The translator’s introduction helped me understand the book better than I otherwise might have. I gleaned two key facts: 1) The mountainous west coast of Japan is snowbound for months of the year, so the title is fairly literal. 2) Hot springs were traditionally places where family men travelled without their wives to enjoy the company of geishas. Such is the case here with the protagonist, Shimamura, who is intrigued by the geisha Komako. Her flighty hedonism seems a good match for his, but they fail to fully connect. His attentions are divided between Komako and Yoko, and a final scene that is surprisingly climactic in a novella so low on plot puts the three and their relationships in danger. I liked the appropriate atmosphere of chilly isolation; the style reminded me of what little I’ve read from Marguerite Duras. I also thought of Silk by Alessandro Baricco and Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden – perhaps those were to some extent inspired by Kawabata?

The translator’s introduction helped me understand the book better than I otherwise might have. I gleaned two key facts: 1) The mountainous west coast of Japan is snowbound for months of the year, so the title is fairly literal. 2) Hot springs were traditionally places where family men travelled without their wives to enjoy the company of geishas. Such is the case here with the protagonist, Shimamura, who is intrigued by the geisha Komako. Her flighty hedonism seems a good match for his, but they fail to fully connect. His attentions are divided between Komako and Yoko, and a final scene that is surprisingly climactic in a novella so low on plot puts the three and their relationships in danger. I liked the appropriate atmosphere of chilly isolation; the style reminded me of what little I’ve read from Marguerite Duras. I also thought of Silk by Alessandro Baricco and Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden – perhaps those were to some extent inspired by Kawabata?

Favorite wintry passage:

“From the gray sky, framed by the window, the snow floated toward them in great flakes, like white peonies. There was something quietly unreal about it.”

My rating:

I’ve also been slowly working my way through The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen, a spiritual quest memoir with elements of nature and travel writing, and skimming Francis Spufford’s dense book about the history of English exploration in polar regions, I May Be Some Time (“Heat and cold probably provide the oldest metaphors for emotion that exist.”).

On next year’s docket: The Library of Ice by Nancy Campbell (on my Kindle) and Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson

Last year I had a whole article on perfect winter reads published in the Nov/Dec issue of Bookmarks magazine. Buried in Print spotted it and sent this tweet. If you have access to the magazine via your local library, be sure to have a look!

Have you read any particularly wintry books recently?

November’s Novellas: A Wrap-Up

Yesterday was my husband’s birthday. Baking him the world’s most complicated cake on Wednesday evening and taking Thursday off for a birthday outing to Salisbury for the Terry Pratchett exhibit at the town’s museum and the Christmas-decorated rooms at Mompesson House are my collective excuse for not writing up the last of November’s novellas until now.

For the most part I had a great time reading novellas last month. However, there were three I abandoned: Mornings in Mexico by D.H Lawrence (p. 11), whose random, repetitive observations lead to no bigger picture; So Long, See You Tomorrow by William Maxwell (p. 28), which is understated to the point of nothing really happening; and Jaguars and Electric Eels by Alexander von Humboldt (p. 6), which has that dry old style that’s hard to engage with. (I’ll plan to encounter snatches of his writing via Andrea Wulf’s biography instead.)

To my disappointment, I find I can’t make generalizations about the correlation between a book’s page count and its quality: a great book stands out no matter its length. But as Joe Hill (Stephen King’s son) said of his latest work, a set of four short novels, a novella should be “all killer, no filler.” Three of the five I review today definitely meet those criteria, impressing me with the literal and/or emotional ground covered.

To my disappointment, I find I can’t make generalizations about the correlation between a book’s page count and its quality: a great book stands out no matter its length. But as Joe Hill (Stephen King’s son) said of his latest work, a set of four short novels, a novella should be “all killer, no filler.” Three of the five I review today definitely meet those criteria, impressing me with the literal and/or emotional ground covered.

Below are the novellas I didn’t manage to get to this past November. Perhaps they’ll hang around until next year, unless I get a burning urge to read one or more of them before then:

(On the Kindle: Record of a Night Too Brief by Hiromi Kawakami and Spring Garden by Tomoka Shibasaki.)

The Gourmet by Muriel Barbery

(translated from the French by Alison Anderson)

[112 pages]

Pierre Arthens, France’s most formidable food critic, is on his deathbed reliving his most memorable meals and searching for one elusive flavor to experience again before he dies. He’s proud of his accomplishments – “I have covered the entire range of culinary art, for I am an encyclopedic esthete who is always one dish ahead of the game” – and expresses no remorse for his affairs and his coldness as a father. This takes place in the same apartment building as The Elegance of the Hedgehog and is in short first-person chapters narrated by various figures from Arthens’ life. His wife, his children and his doctor are expected, but we also hear from the building’s concierge, a homeless man he passed every day for ten years, and even a sculpture in his study. I liked Arthens’ grandiose style and the descriptions of over-the-top meals but, unlike the somewhat similar The Debt to Pleasure by John Lanchester, this doesn’t have much of a payoff.

Pierre Arthens, France’s most formidable food critic, is on his deathbed reliving his most memorable meals and searching for one elusive flavor to experience again before he dies. He’s proud of his accomplishments – “I have covered the entire range of culinary art, for I am an encyclopedic esthete who is always one dish ahead of the game” – and expresses no remorse for his affairs and his coldness as a father. This takes place in the same apartment building as The Elegance of the Hedgehog and is in short first-person chapters narrated by various figures from Arthens’ life. His wife, his children and his doctor are expected, but we also hear from the building’s concierge, a homeless man he passed every day for ten years, and even a sculpture in his study. I liked Arthens’ grandiose style and the descriptions of over-the-top meals but, unlike the somewhat similar The Debt to Pleasure by John Lanchester, this doesn’t have much of a payoff.

A favorite passage:

“After decades of grub, deluges of wine and alcohol of every sort, after a life spent in butter, cream, sauce, and oil in constant, knowingly orchestrated and meticulously cajoled excess, my trustiest right-hand men, Sir Liver and his associate Stomach, are doing marvelously well and it is my heart that is giving out.”

Silk by Alessandro Baricco

(translated from the Italian by Guido Waldman)

[104 pages]

The main action is set between 1861 and 1874, as married French merchant Hervé Joncour makes four journeys to and from Japan to acquire silkworms. “This place, Japan, where precisely is it?” he asks before his first trip. “Just keep going. Right to the end of the world,” Baldabiou, the silk mill owner, replies. On his first journey, Joncour is instantly captivated by his Japanese advisor’s concubine, though they haven’t exchanged a single word, and from that moment on nothing in his life can make up for the lack of her. At first I found the book slightly repetitive and fable-like, but as it went on I grew more impressed with the seeds Baricco has planted that lead to a couple of major surprises. At the end I went back and reread a number of chapters to pick up on the clues. I’d had this book recommended from a variety of quarters, first by Karen Shepard when I interviewed her for Bookkaholic in 2013, so I’m glad I finally found a copy in a charity shop.

The main action is set between 1861 and 1874, as married French merchant Hervé Joncour makes four journeys to and from Japan to acquire silkworms. “This place, Japan, where precisely is it?” he asks before his first trip. “Just keep going. Right to the end of the world,” Baldabiou, the silk mill owner, replies. On his first journey, Joncour is instantly captivated by his Japanese advisor’s concubine, though they haven’t exchanged a single word, and from that moment on nothing in his life can make up for the lack of her. At first I found the book slightly repetitive and fable-like, but as it went on I grew more impressed with the seeds Baricco has planted that lead to a couple of major surprises. At the end I went back and reread a number of chapters to pick up on the clues. I’d had this book recommended from a variety of quarters, first by Karen Shepard when I interviewed her for Bookkaholic in 2013, so I’m glad I finally found a copy in a charity shop.

Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick

[151 pages]

Hardwick’s 1979 work is composed of (autobiographical?) fragments about the people and places that make up a woman’s remembered past. Elizabeth shares a New York City apartment with a gay man; lovers come and go; she mourns for Billie Holiday; there are brief interludes in Amsterdam and other foreign destinations. She sends letters to “Dearest M.” and back home to Kentucky, where her mother raised nine children. (“My mother’s femaleness was absolute, ancient, and there was a peculiar, helpless assertiveness about it. … This fateful fertility kept her for most of her life under the dominion of nature.”) There’s some astonishingly good writing here, but as was the case for me with Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, I couldn’t quite see how it was all meant to fit together.

Hardwick’s 1979 work is composed of (autobiographical?) fragments about the people and places that make up a woman’s remembered past. Elizabeth shares a New York City apartment with a gay man; lovers come and go; she mourns for Billie Holiday; there are brief interludes in Amsterdam and other foreign destinations. She sends letters to “Dearest M.” and back home to Kentucky, where her mother raised nine children. (“My mother’s femaleness was absolute, ancient, and there was a peculiar, helpless assertiveness about it. … This fateful fertility kept her for most of her life under the dominion of nature.”) There’s some astonishingly good writing here, but as was the case for me with Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, I couldn’t quite see how it was all meant to fit together.

Some favorite passages:

“The stain of place hangs on not as a birthright but as a sort of artifice, a bit of cosmetic.”

“The bright morning sky that day had a rare and blue fluffiness, as if a vacuum cleaner had raced across the heavens as a weekly, clarifying duty.”

“On the battered calendar of the past, the back-glancing flow of numbers, I had imagined there would be felicitous notations of entrapments and escapes, days in the South with their insinuating feline accent, and nights in the East, showing a restlessness as beguiling as the winds of Aeolus. And myself there, marking the day with an I.”

Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West

[110 pages]

West was a contemporary of F. Scott Fitzgerald; in fact, the story goes that when he died in a car accident at age 37, he had been rushing to Fitzgerald’s wake, and the friends were given adjoining rooms in a Los Angeles funeral home. Like The Great Gatsby, this is a very American tragedy and state-of-the-nation novel. “Miss Lonelyhearts” (never given any other name) is a male advice columnist for the New York Post-Dispatch. His letters come from a pitiable cross section of humanity: the abused, the downtrodden, the unloved. Not surprisingly, the secondhand woes start to get him down (“his heart remained a congealed lump of icy fat”), and he turns to drink and womanizing for escape. Indeed, I was startled by how explicit the language and sexual situations are; this doesn’t feel like a book from 1933. West’s picture of how beleaguered compassion can turn to indifference really struck me, and the last few chapters, in which a drastic change of life is proffered but then cruelly denied, are masterfully plotted. The 2014 Daunt Books reissue has been given a cartoon cover and a puff from Jonathan Lethem to emphasize how contemporary it feels.

West was a contemporary of F. Scott Fitzgerald; in fact, the story goes that when he died in a car accident at age 37, he had been rushing to Fitzgerald’s wake, and the friends were given adjoining rooms in a Los Angeles funeral home. Like The Great Gatsby, this is a very American tragedy and state-of-the-nation novel. “Miss Lonelyhearts” (never given any other name) is a male advice columnist for the New York Post-Dispatch. His letters come from a pitiable cross section of humanity: the abused, the downtrodden, the unloved. Not surprisingly, the secondhand woes start to get him down (“his heart remained a congealed lump of icy fat”), and he turns to drink and womanizing for escape. Indeed, I was startled by how explicit the language and sexual situations are; this doesn’t feel like a book from 1933. West’s picture of how beleaguered compassion can turn to indifference really struck me, and the last few chapters, in which a drastic change of life is proffered but then cruelly denied, are masterfully plotted. The 2014 Daunt Books reissue has been given a cartoon cover and a puff from Jonathan Lethem to emphasize how contemporary it feels.

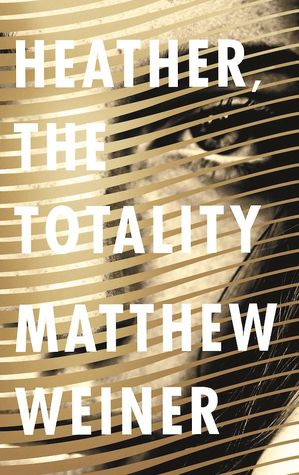

Heather, the Totality by Matthew Weiner

[134 pages]

This was very nearly a one-sitting read for me: Clare gave me a copy at our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel decision meeting and I read all but a few pages on the train home from London. Famously, Matthew Weiner is the creator of Mad Men, but instead of 1960s stylishness this debut novella is full of all-too-believable creepiness and a crescendo of dubious decisions. Mark and Karen Breakstone have one beloved daughter, Heather. We follow them for years, getting little snapshots of a normal middle-class family. One summer, as their New York City apartment building is being renovated, the teenaged Heather catches the eye of a construction worker who has a criminal past – as we’ve learned through a parallel narrative about his life. I had no idea what I would conclude about this book until the last few pages; it was all going to be a matter of how Weiner brought things together. And he does so really satisfyingly, I think. It’s a subtle, Hitchcockian story, and that title is so sly: We never get the totality of anyone; we only see shards here and there – something the cover portrays very well – and make judgments we later have to rethink.

This was very nearly a one-sitting read for me: Clare gave me a copy at our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel decision meeting and I read all but a few pages on the train home from London. Famously, Matthew Weiner is the creator of Mad Men, but instead of 1960s stylishness this debut novella is full of all-too-believable creepiness and a crescendo of dubious decisions. Mark and Karen Breakstone have one beloved daughter, Heather. We follow them for years, getting little snapshots of a normal middle-class family. One summer, as their New York City apartment building is being renovated, the teenaged Heather catches the eye of a construction worker who has a criminal past – as we’ve learned through a parallel narrative about his life. I had no idea what I would conclude about this book until the last few pages; it was all going to be a matter of how Weiner brought things together. And he does so really satisfyingly, I think. It’s a subtle, Hitchcockian story, and that title is so sly: We never get the totality of anyone; we only see shards here and there – something the cover portrays very well – and make judgments we later have to rethink.