Catching Up: Mini Reviews of Some Notable Reads from Last Year

I do all my composition on an ancient PC (unconnected to the Internet) in a corner of our lounge. On top of the CPU sit piles of books waiting to be reviewed. Some have been residing there for an embarrassingly long time since I finished reading them; others were only recently added to the stack but had previously languished on my set-aside shelf. I think the ‘oldest’ of the set below is the Olson, which I started reading in November 2019. In every case, the book earned a spot on the pile because I felt it was worth a review, but I’ll stick to a brief paragraph on why each was memorable. Bonus: I get my Post-its back, and can reshelve the books so they get packed sensibly for our upcoming move.

Fiction

How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti (2012): My second from Heti, after Motherhood; both landed with me because they nail aspects of my state of mind. Heti writes autofiction about writers dithering about their purpose in life. Here Sheila is working in a hair salon while trying to finish her play – some absurdist dialogue is set out in script form – and hanging out with artists like her best friend Margaux. The sex scenes are gratuitous and kinda gross. In general, I alternated between sniggering (especially at the ugly painting competition) and feeling seen: Sheila expects fate to decide things for her; God forbid she should ever have to make an actual choice. Heti is self-deprecating about an admittedly self-indulgent approach, and so funny on topics like mansplaining. This was longlisted for the Women’s Prize in 2013. (Little Free Library)

How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti (2012): My second from Heti, after Motherhood; both landed with me because they nail aspects of my state of mind. Heti writes autofiction about writers dithering about their purpose in life. Here Sheila is working in a hair salon while trying to finish her play – some absurdist dialogue is set out in script form – and hanging out with artists like her best friend Margaux. The sex scenes are gratuitous and kinda gross. In general, I alternated between sniggering (especially at the ugly painting competition) and feeling seen: Sheila expects fate to decide things for her; God forbid she should ever have to make an actual choice. Heti is self-deprecating about an admittedly self-indulgent approach, and so funny on topics like mansplaining. This was longlisted for the Women’s Prize in 2013. (Little Free Library)

The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard (1990): The first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles, read for a book club meeting last January. I could hardly believe the publication date; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of daily life in 1937–8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex that it seems it must have been written in the 1940s. The retrospective angle, however, allows for subtle commentary on how limited women’s lives were, locked in by marriage and pregnancies. Sexual abuse is also calmly reported. One character is a lesbian, but everyone believes her partner is just a friend. The cousins’ childhood japes are especially enjoyable. And, of course, war is approaching. It’s all very Downton Abbey. I launched straight into the second book afterwards, but stalled 60 pages in. I’ll aim to get back into the series later this year. (Free mall bookshop)

The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard (1990): The first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles, read for a book club meeting last January. I could hardly believe the publication date; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of daily life in 1937–8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex that it seems it must have been written in the 1940s. The retrospective angle, however, allows for subtle commentary on how limited women’s lives were, locked in by marriage and pregnancies. Sexual abuse is also calmly reported. One character is a lesbian, but everyone believes her partner is just a friend. The cousins’ childhood japes are especially enjoyable. And, of course, war is approaching. It’s all very Downton Abbey. I launched straight into the second book afterwards, but stalled 60 pages in. I’ll aim to get back into the series later this year. (Free mall bookshop)

Nonfiction

Keeper: Living with Nancy—A journey into Alzheimer’s by Andrea Gillies (2009): The inaugural Wellcome Book Prize winner. The Prize expanded in focus over a decade; I don’t think a straightforward family memoir like this would have won later on. Gillies’ family relocated to remote northern Scotland and her elderly mother- and father-in-law, Nancy and Morris, moved in. Morris was passive, with limited mobility; Nancy was confused and cantankerous, often treating Gillies like a servant. (“There’s emptiness behind her eyes, something missing that used to be there. It’s sinister.”) She’d try to keep her cool but often got frustrated and contradicted her mother-in-law’s delusions. Gillies relays facts about Alzheimer’s that I knew from In Pursuit of Memory. What has remained with me is a sense of just how gruelling the caring life is. Gillies could barely get any writing done because if she turned her back Nancy might start walking to town, or – the single most horrific incident that has stuck in my mind – place faeces on the bookshelf. (Secondhand purchase)

Keeper: Living with Nancy—A journey into Alzheimer’s by Andrea Gillies (2009): The inaugural Wellcome Book Prize winner. The Prize expanded in focus over a decade; I don’t think a straightforward family memoir like this would have won later on. Gillies’ family relocated to remote northern Scotland and her elderly mother- and father-in-law, Nancy and Morris, moved in. Morris was passive, with limited mobility; Nancy was confused and cantankerous, often treating Gillies like a servant. (“There’s emptiness behind her eyes, something missing that used to be there. It’s sinister.”) She’d try to keep her cool but often got frustrated and contradicted her mother-in-law’s delusions. Gillies relays facts about Alzheimer’s that I knew from In Pursuit of Memory. What has remained with me is a sense of just how gruelling the caring life is. Gillies could barely get any writing done because if she turned her back Nancy might start walking to town, or – the single most horrific incident that has stuck in my mind – place faeces on the bookshelf. (Secondhand purchase)

Reflections from the North Country by Sigurd F. Olson (1976): Olson was a well-known environmental writer in his time, also serving as president of the National Parks Association. Somehow I hadn’t heard of him before my husband picked this out at random. Part of a Minnesota Heritage Book series, this collection of passionate, philosophically oriented essays about the state of nature places him in the vein of Aldo Leopold – before-their-time conservationists. He ponders solitude, wilderness and human nature, asking what is primal in us and what is due to unfortunate later developments. His counsel includes simplicity and wonder rather than exploitation and waste. The chief worry that comes across is that people are now so cut off from nature they can’t see what they’re missing – and destroying. It can be depressing to read such profound 1970s works; had we heeded environmental prophets like Olson, we could have changed course before it was too late. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Reflections from the North Country by Sigurd F. Olson (1976): Olson was a well-known environmental writer in his time, also serving as president of the National Parks Association. Somehow I hadn’t heard of him before my husband picked this out at random. Part of a Minnesota Heritage Book series, this collection of passionate, philosophically oriented essays about the state of nature places him in the vein of Aldo Leopold – before-their-time conservationists. He ponders solitude, wilderness and human nature, asking what is primal in us and what is due to unfortunate later developments. His counsel includes simplicity and wonder rather than exploitation and waste. The chief worry that comes across is that people are now so cut off from nature they can’t see what they’re missing – and destroying. It can be depressing to read such profound 1970s works; had we heeded environmental prophets like Olson, we could have changed course before it was too late. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Educating Alice: Adventures of a Curious Woman by Alice Steinbach (2004): I’d loved her earlier travel book Without Reservations. Here she sets off on a journey of discovery and lifelong learning. I included the first essay, about enrolling in cooking lessons in Paris, in my foodie 20 Books of Summer 2020. In other chapters she takes dance lessons in Kyoto, appreciates art in Florence and Havana, walks in Jane Austen’s footsteps in Winchester and environs, studies garden design in Provence, takes a creative writing workshop in Prague, and trains Border collies in Scotland. It’s clear she loves meeting new people and chatting – great qualities in a journalist. By this time she had quit her job with the Baltimore Sun so was free to explore and make her life what she wanted. She thinks back to childhood memories of her Scottish grandmother, and imagines how she’d describe her adventures to her gentleman friend, Naohiro. She recreates everything in a way that makes this as fluent as any novel, such that I’d even dare recommend it to fiction-only readers. (Free mall bookshop)

Educating Alice: Adventures of a Curious Woman by Alice Steinbach (2004): I’d loved her earlier travel book Without Reservations. Here she sets off on a journey of discovery and lifelong learning. I included the first essay, about enrolling in cooking lessons in Paris, in my foodie 20 Books of Summer 2020. In other chapters she takes dance lessons in Kyoto, appreciates art in Florence and Havana, walks in Jane Austen’s footsteps in Winchester and environs, studies garden design in Provence, takes a creative writing workshop in Prague, and trains Border collies in Scotland. It’s clear she loves meeting new people and chatting – great qualities in a journalist. By this time she had quit her job with the Baltimore Sun so was free to explore and make her life what she wanted. She thinks back to childhood memories of her Scottish grandmother, and imagines how she’d describe her adventures to her gentleman friend, Naohiro. She recreates everything in a way that makes this as fluent as any novel, such that I’d even dare recommend it to fiction-only readers. (Free mall bookshop)

Kings of the Yukon: An Alaskan River Journey by Adam Weymouth (2018): I didn’t get the chance to read this when it was shortlisted for, and then won, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, but I received a copy from my wish list for Christmas that year. Alaska is a place that attracts outsiders and nonconformists. During the summer of 2016, Weymouth undertook a voyage by canoe down the nearly 2,000 miles of the Yukon River – the same epic journey made by king/Chinook salmon. He camps alongside the river bank in a tent, often with his partner, Ulli. He also visits a fish farm, meets reality TV stars and native Yup’ik people, and eats plenty of salmon. “I do occasionally consider the ethics of investigating a fish’s decline whilst stuffing my face with it.” Charting the effects of climate change without forcing the issue, he paints a somewhat bleak picture. But his descriptive writing is so lyrical, and his scenes and dialogue so natural, that he kept me eagerly riding along in the canoe with him. (Secondhand copy, gifted)

Kings of the Yukon: An Alaskan River Journey by Adam Weymouth (2018): I didn’t get the chance to read this when it was shortlisted for, and then won, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, but I received a copy from my wish list for Christmas that year. Alaska is a place that attracts outsiders and nonconformists. During the summer of 2016, Weymouth undertook a voyage by canoe down the nearly 2,000 miles of the Yukon River – the same epic journey made by king/Chinook salmon. He camps alongside the river bank in a tent, often with his partner, Ulli. He also visits a fish farm, meets reality TV stars and native Yup’ik people, and eats plenty of salmon. “I do occasionally consider the ethics of investigating a fish’s decline whilst stuffing my face with it.” Charting the effects of climate change without forcing the issue, he paints a somewhat bleak picture. But his descriptive writing is so lyrical, and his scenes and dialogue so natural, that he kept me eagerly riding along in the canoe with him. (Secondhand copy, gifted)

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

20 Books of Summer, #13–14: Ruth Reichl and Alice Steinbach

Just three weeks remain in this challenge. I’m reading another four books towards it, and have two more to pick up during our mini-break to Devon and Dorset this coming weekend. A few of my choices are long and/or slow-moving reads, though, so I have a feeling I’ll be reading right down to the wire…

Today I have another two memoirs linked by France and its cuisine.

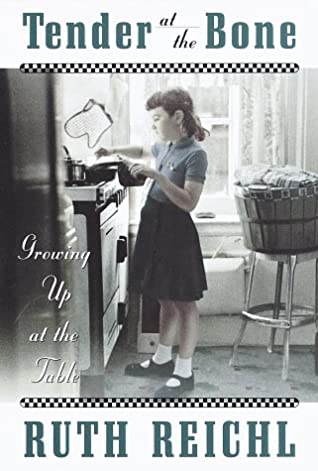

Tender at the Bone: Growing Up at the Table by Ruth Reichl (1998)

(20 Books of Summer, #13) I’ve read Reichl’s memoirs out of order, starting with Garlic and Sapphires (2005), about her time as a New York Times food critic, and moving on to Comfort Me with Apples (2001), about her involvement in California foodie culture in the 1970s–80s. Whether because I’d been primed by the disclaimer in the author’s note (“I have occasionally embroidered. I learned early that the most important thing in life is a good story”) or not, I sensed that certain characters and scenes were exaggerated here. Although I didn’t enjoy her memoir of her first 30 years as much as either of the other two I’d read, it was still worth reading.

(20 Books of Summer, #13) I’ve read Reichl’s memoirs out of order, starting with Garlic and Sapphires (2005), about her time as a New York Times food critic, and moving on to Comfort Me with Apples (2001), about her involvement in California foodie culture in the 1970s–80s. Whether because I’d been primed by the disclaimer in the author’s note (“I have occasionally embroidered. I learned early that the most important thing in life is a good story”) or not, I sensed that certain characters and scenes were exaggerated here. Although I didn’t enjoy her memoir of her first 30 years as much as either of the other two I’d read, it was still worth reading.

The cover image is a genuine photograph taken by Reichl’s German immigrant father, book designer Ernst Reichl, in 1955. Early on, Reichl had to fend for herself in the kitchen: her bipolar mother hoarded discount food even it was moldy, so the family quickly learned to avoid her dishes made with ingredients that were well past their best. Like Eric Asimov and Anthony Bourdain, whose memoirs I’ve also reviewed this summer, Reichl got turned on to food by a top-notch meal in France. Food was a form of self-expression as well as an emotional crutch in many situations to come: during boarding school in Montreal, her rebellious high school years, and while living off of trendy grains and Dumpster finds at a co-op in Berkeley.

Reichl worked with food in many ways during her twenties. She was a waitress during college in Michigan, and a restaurant collective co-owner in California; she gave cooking lessons; she catered parties; and she finally embarked on a career as a restaurant critic. Her travels took her to France (summer camp counselor; later, wine aficionado), Morocco (with her college roommate), and Crete (a honeymoon visit to her favorite professor). Raised in New York City, she makes her way back there frequently, too. Overall, the book felt a bit scattered to me, with few if any recipes that I would choose to make, and the relationship with a mentally ill mother was so fraught that I will probably avoid Reichl’s two later books focusing on her mother.

Source: Awesomebooks.com

My rating:

Educating Alice: Adventures of a Curious Woman by Alice Steinbach (2004)

(20 Books of Summer, #14) Steinbach makes a repeat appearance in my summer reading docket: her 2000 travel book Without Reservations was one of my 2018 selections. In that book, she took a sabbatical during her 50s to explore Paris, England, and Italy. Here she continues her efforts at lifelong learning by taking up some sort of lessons everywhere she goes. The long first section sees her back in Paris, enrolling at the Hotel Ritz’s Escoffier École de Gastronomie Française. She’s self-conscious about having joined late, being older than the other students and having to rely on the translator rather than the chef’s instructions, but she’s determined to keep up as the class makes omelettes, roast quail and desserts.

(20 Books of Summer, #14) Steinbach makes a repeat appearance in my summer reading docket: her 2000 travel book Without Reservations was one of my 2018 selections. In that book, she took a sabbatical during her 50s to explore Paris, England, and Italy. Here she continues her efforts at lifelong learning by taking up some sort of lessons everywhere she goes. The long first section sees her back in Paris, enrolling at the Hotel Ritz’s Escoffier École de Gastronomie Française. She’s self-conscious about having joined late, being older than the other students and having to rely on the translator rather than the chef’s instructions, but she’s determined to keep up as the class makes omelettes, roast quail and desserts.

Full disclosure: I’ve only read the first chapter for now as it’s the only one directly relevant to food – in others she takes dance lessons in Japan, studies art in Cuba, trains Border collies in Scotland, etc. – but I was enjoying it and will go back to it before the end of the year.

Source: Free bookshop

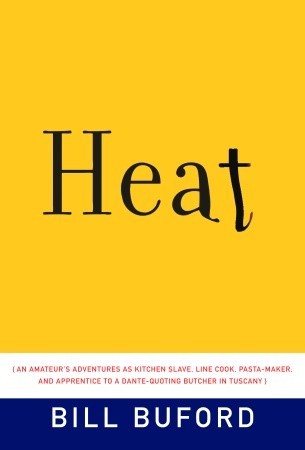

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.” I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list. Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl. We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

I first read this nearly four years ago (you can find my initial review in an

I first read this nearly four years ago (you can find my initial review in an

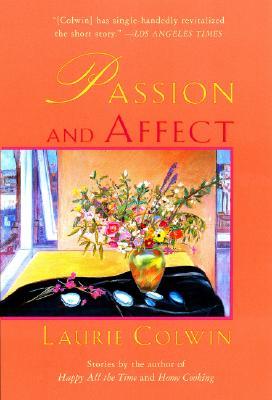

I mostly know Colwin as a food writer, but she also published fiction. This subtle story collection turns on quiet, mostly domestic dramas: people falling in and out of love, stepping out on their spouses and trying to protect their families. I didn’t particularly engage with the central two stories about cousins Vincent and Guido (characters from her novel Happy All the Time, which I abandoned a few years back), but the rest more than made up for them.

I mostly know Colwin as a food writer, but she also published fiction. This subtle story collection turns on quiet, mostly domestic dramas: people falling in and out of love, stepping out on their spouses and trying to protect their families. I didn’t particularly engage with the central two stories about cousins Vincent and Guido (characters from her novel Happy All the Time, which I abandoned a few years back), but the rest more than made up for them.

Like her protagonist, Sophie Caco, Danticat was raised by her aunt in Haiti and reunited with her parents in the USA at age 12. As Sophie grows up and falls in love with an older musician, she and her mother are both haunted by sexual trauma that nothing – not motherhood, not a long-awaited return to Haiti – seems to heal. I loved the descriptions of Haiti (“The sun, which was once god to my ancestors, slapped my face as though I had done something wrong. The fragrance of crushed mint leaves and stagnant pee alternated in the breeze” and “The stars fell as though the glue that held them together had come loose”), and the novel gives a powerful picture of a maternal line marred by guilt and an obsession with sexual purity. However, compared to Danticat’s later novel, Claire of the Sea Light, I found the narration a bit flat and the story interrupted – thinking particularly of the gap between ages 12 and 18 for Sophie. (Another Oprah’s Book Club selection.)

Like her protagonist, Sophie Caco, Danticat was raised by her aunt in Haiti and reunited with her parents in the USA at age 12. As Sophie grows up and falls in love with an older musician, she and her mother are both haunted by sexual trauma that nothing – not motherhood, not a long-awaited return to Haiti – seems to heal. I loved the descriptions of Haiti (“The sun, which was once god to my ancestors, slapped my face as though I had done something wrong. The fragrance of crushed mint leaves and stagnant pee alternated in the breeze” and “The stars fell as though the glue that held them together had come loose”), and the novel gives a powerful picture of a maternal line marred by guilt and an obsession with sexual purity. However, compared to Danticat’s later novel, Claire of the Sea Light, I found the narration a bit flat and the story interrupted – thinking particularly of the gap between ages 12 and 18 for Sophie. (Another Oprah’s Book Club selection.)

Maybe you grew up in or near a town like Mooreland, Indiana (population 300). Born in 1965 when her brother and sister were 13 and 10, Kimmel was affectionately referred to as an “Afterthought” and nicknamed “Zippy” for her boundless energy. Gawky and stubborn, she pulled every trick in the book to try to get out of going to Quaker meetings three times a week, preferring to go fishing with her father. The short chapters, headed by family or period photos, are sets of thematic childhood anecdotes about particular neighbors, school friends and pets. I especially loved her parents: her mother reading approximately 40,000 science fiction novels while wearing a groove into the couch, and her father’s love of the woods (which he called his “church”) and elaborate preparations for camping trips an hour away.

Maybe you grew up in or near a town like Mooreland, Indiana (population 300). Born in 1965 when her brother and sister were 13 and 10, Kimmel was affectionately referred to as an “Afterthought” and nicknamed “Zippy” for her boundless energy. Gawky and stubborn, she pulled every trick in the book to try to get out of going to Quaker meetings three times a week, preferring to go fishing with her father. The short chapters, headed by family or period photos, are sets of thematic childhood anecdotes about particular neighbors, school friends and pets. I especially loved her parents: her mother reading approximately 40,000 science fiction novels while wearing a groove into the couch, and her father’s love of the woods (which he called his “church”) and elaborate preparations for camping trips an hour away. This was a breezy, delightful novel perfect for summer reading. In 1962 Natalie Marx’s family is looking for a vacation destination and sends query letters to various Vermont establishments. Their reply from the Inn at Lake Devine (proprietress: Ingrid Berry) tactfully but firmly states that the inn’s regular guests are Gentiles. In other words, no Jews allowed. The adolescent Natalie is outraged, and when the chance comes for her to infiltrate the Inn as the guest of one of her summer camp roommates, she sees it as a secret act of revenge.

This was a breezy, delightful novel perfect for summer reading. In 1962 Natalie Marx’s family is looking for a vacation destination and sends query letters to various Vermont establishments. Their reply from the Inn at Lake Devine (proprietress: Ingrid Berry) tactfully but firmly states that the inn’s regular guests are Gentiles. In other words, no Jews allowed. The adolescent Natalie is outraged, and when the chance comes for her to infiltrate the Inn as the guest of one of her summer camp roommates, she sees it as a secret act of revenge. In 1993 Steinbach, then in her fifties, took a sabbatical from her job as a Baltimore Sun journalist to travel for nine months straight in Paris, England and Italy. As a divorcee with two grown sons, she no longer felt shackled to her Maryland home and wanted to see if she could recover a more spontaneous and adventurous version of herself and not be defined exclusively by her career. Her innate curiosity and experience as a reporter helped her to quickly form relationships with other English-speaking tourists, which was an essential for someone traveling alone.

In 1993 Steinbach, then in her fifties, took a sabbatical from her job as a Baltimore Sun journalist to travel for nine months straight in Paris, England and Italy. As a divorcee with two grown sons, she no longer felt shackled to her Maryland home and wanted to see if she could recover a more spontaneous and adventurous version of herself and not be defined exclusively by her career. Her innate curiosity and experience as a reporter helped her to quickly form relationships with other English-speaking tourists, which was an essential for someone traveling alone.