Tag Archives: missionaries

20 Books of Summer, #19–20: Heat & The Gospel of Trees

Finishing off my summer reading project with a stellar biography-cum-travel book about Italian cuisine and a family memoir about missionary work in Haiti in the 1980s.

Heat by Bill Buford (2006)

(20 Books of Summer, #19) The long subtitle gives you an outline of the contents: “An Amateur’s Adventures as Kitchen Slave, Line Cook, Pasta-Maker, and Apprentice to a Dante-Quoting Butcher in Tuscany.” If Buford’s name sounds familiar, it’s because he was the founding editor of Granta magazine and publisher at Granta Books, but by the time he wrote this he was a staff writer for the New Yorker.

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

In between behind-the-scenes looks at frantic or dull sessions of food prep (“after you’ve made a couple thousand or so of these little ears [orecchiette pasta], your mind wanders. You think about anything, everything, whatever, nothing”), Buford traces Batali’s culinary pedigree through Italy and London, where Batali learned from the first modern celebrity chef, Marco Pierre White, and gives pen portraits of the rest of the kitchen staff. At first only trusted with chopping herbs, the author develops his skills enough that he’s allowed to work the pasta and grill stations, and to make polenta for 200 for a benefit dinner in Nashville.

Later, Buford spends stretches of several months in Italy as an apprentice to a pasta-maker and a Tuscan butcher. His obsession with Italian cuisine is such that he has to know precisely when egg started to replace water in pasta dough in historical cookbooks, and is distressed when the workers at the pasta museum in Rome can’t give him a definitive answer. All the same, the author never takes himself too seriously: he knows it’s ridiculous for a clumsy, unfit man in his mid-forties to be entertaining dreams of working in a restaurant for real, and he gives self-deprecating accounts of his mishaps in the various kitchens he toils in:

to stir the polenta, I was beginning to feel I had to be in the polenta. Would I finish cooking it before I was enveloped by it and became the darkly sauced meaty thing it was served with?

Compared to Kitchen Confidential, I found this less brash and more polished. You still get the sense of macho posturing from a lot of the figures profiled, but of course this author is not going to be in a position to interrogate food culture’s overweening masculinity. However, he does take a stand in support of small-scale food production:

Small food: by hand and therefore precious, hard to find. Big food: from a factory and therefore cheap, abundant. Just about every preparation I learned in Italy was handmade and involved learning how to use my own hands differently. … Food made by hand is an act of defiance and runs contrary to everything in our modernity. Find it; eat it; it will go.

This is exactly what I want from food writing: interesting nuggets of trivia and insight, a quick pace, humor, and mouthwatering descriptions. If the restaurant world lures you at all, you must read this one.

- Nice connections with my other summer reading: there are mentions of both Eric Asimov and Ruth Reichl visiting Babbo in their capacity as food critics for the New York Times.

- This also induced a weird case of reverse déjà vu: a book I reviewed last summer for BookBrowse, Hungry by Jeff Gordinier, is so similar that it must have been patterned on Heat: the punchy one-word title; a New York journalist follows an internationally known chef (in that case, René Redzepi) and surveys culinary trends.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

Source: From my dad

My rating:

The Gospel of Trees by Apricot Irving (2018)

(20 Books of Summer, #20) Irving’s parents were volunteer missionaries to Haiti between 1982 and 1991, when she was aged six to 15. Her father, Jon, was trained as an agronomist, and his passion was for planting trees to combat the negative effects of deforestation on the island (erosion and worsened flooding). But in a country blighted by political unrest, AIDS and poverty, people can’t think long-term; they need charcoal to light their stoves, so they cut down trees.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Irving drew on letters and cassette tape recordings, newsletters, and journals (her parents’ and her own) to recreate the decade in Haiti and the years since. This debut book was many years in the making – she started the project in 2001. “I inherited my father’s anger and his perfectionism. Haiti was a wound, an unhealed scab that I was afraid to pick open. But I knew that unless I faced that broken history, my own buried grief, like my father’s, would explode ways I couldn’t predict.”

She and her parents returned to the country after the 2010 earthquake: they were volunteers with a relief organization, while she reported for the This American Life radio program. I loved the ambivalent portrait of Haiti and, especially, of Jon, but couldn’t muster up much interest in secondary characters, hoped for more discussion of (loss of) faith, and thought the book about 80 pages too long. Irving writes wonderfully, though, especially when musing on Haiti’s pre-Columbian history; I’d gladly read a nature book about her life in Oregon, or a novel – in tone this reminded me of The Poisonwood Bible.

Some favorite lines:

If, like my father, you suffer from a savior complex, Haiti is a bleak assignment, but if you are able to enter it unguarded, shielded only by curiosity, you will find the sorrows entangled with a defiant joy.

My family had moved to Haiti to try to help, but instead, we learned our limitations. Failure can be a wise friend. We felt crushed at times; found it difficult to breathe; and yet the experience carved into each of us an understanding of loss, the weight of compassion. We learned how small we were when measured against the world’s great sorrow.

Source: Bargain book from Amazon last year

My rating:

And a DNF:

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

I gave up after 38 pages. I’ve long meant to try Oates, but her oeuvre is daunting. An Oprah’s Book Club selection seemed like a safe bet. I found the quirky all-American family saga approach somewhat similar to John Irving or Richard Russo, but Judd’s narration is annoyingly perky, and already I was impatient to find out what happened to his sister Marianne on Valentine’s Day 1976. I’ll give it a few years and try again. In the meantime, maybe I’ll try Oates in a different genre.

Looking back, Heat was the clear highlight of my 20 Books, closely followed by My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki. I also really enjoyed the foodoirs by Anthony Bourdain, Nina Mingya Powles and Luisa Weiss. It’s funny how much I love foodie lit given that I don’t cook. As Alice Steinbach puts it, “while we all like to eat, we like it more when someone else does the cooking.”

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread, Ella Minnow Pea. Ideally, I would not have had to include my two skims and one partial read in the total, but I ran out of time in August to substitute in three more books. I’m happy enough with my showing this year, but next time I plan to build in more flexibility – or cheating, whichever you wish to call it – to ensure that I manage 20 solid reads.

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread, Ella Minnow Pea. Ideally, I would not have had to include my two skims and one partial read in the total, but I ran out of time in August to substitute in three more books. I’m happy enough with my showing this year, but next time I plan to build in more flexibility – or cheating, whichever you wish to call it – to ensure that I manage 20 solid reads.

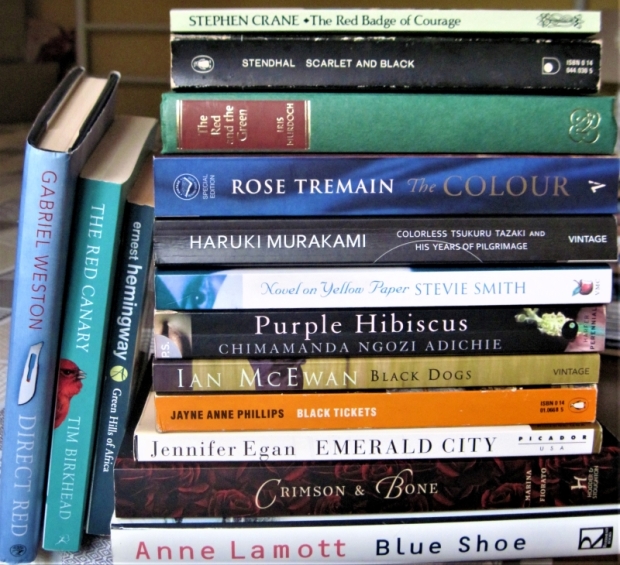

I already have a color theme planned for 20 Books of Summer 2021! Here are 15 books that I own, mostly fiction, that would fit the bill:

As wildcard selections and/or substitutes, I will also allow:

- Books with “light”, “dark”, or “bright” in the title

- Kindle or library books, though I’d like the focus to remain on print books I own.

- If I’m really stuck, book covers/jackets in a rainbow of colors. I’ll skip orange because Penguin paperbacks are too plentiful in my book collection, but I have some nice red, yellow, green, blue, purple and pink covers to choose from.

Doorstopper of the Month: A Reread of The Poisonwood Bible (1998)

“The fallen Congo came to haunt even our little family, we messengers of goodwill adrift on a sea of mistaken intentions.”

You may have gathered by now that I struggle with rereading. Often I find that on a second reading a book doesn’t live up to my memory of it – last year I reread just four books, and I rated each one a star lower than I had the first time. But that wasn’t the case with my September book club book, Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible, which I’ve just flown through in 11 days. I first read it in the spring of 2002 or 2003, so maybe it’s that I’d allowed enough time to pass for it to be almost completely fresh – or that I was in a better frame of mind to appreciate its picture of harmful ideologies in a postcolonial setting. In any case, this time it struck me as a masterpiece, and has instantly leapt onto my favorites list.

Here’s what I’d remembered about The Poisonwood Bible after the passage of 16–17 years:

- It’s about a missionary family in Africa, and narrated by the daughters.

- One of the sisters marries an African.

- The line “Nathan was made frantic by sex” (except I had it fixed incorrectly in my mind; it’s actually “Nathan was made feverish by sex”).

Everything else I’d forgotten. Here’s what stood out on my second reading:

- Surely one of the best opening lines ever? (Though technically there’s a prologue that comes before it.) “We came from Bethlehem, Georgia, bearing Betty Crocker cake mixes into the jungle.”

- The book is actually narrated in turns by the wife and four daughters of Southern Baptist missionary Nathan Price, who arrives in the Congo with his family in 1959. These five voices are a triumph of first-person narration, so distinct and arising organically from the characters’ personalities and experiences. The mother, Orleanna, writes from the future in despondent isolation – a hint right from the beginning that this venture is not going to end well. Fifteen-year-old Rachel is a selfish, ditzy blonde who speaks in malapropisms and period slang and misses everything about American culture. Leah, one of the 13-year-olds, is whip-smart and earnest; she idolizes their father and echoes his religious language. Her twin, Adah, who was born with partial paralysis, rarely speaks but has an intricate inner life she expresses through palindromes, cynical poetry and plays on words. And Ruth May, just five years old, sees more than she understands and sets it all across plainly but wittily.

- Nathan’s arrogant response to the ‘native customs’ is excruciating. His first prayer, spoken to bless the meal the people of Kilanga give in welcome, quickly becomes a diatribe against nakedness, and he later rails against polygamy and witch doctors and tries to enforce child baptism. When he refuses to take their housekeeper Mama Tataba’s advice on planting, all of the seeds he brought from home wash away in the first rainstorm. On a second attempt he meekly makes the raised beds she recommended, and keeps away from the poisonwood that made him break out in a nasty rash. This garden he plants is a metaphor for control versus adaptation.

- Brother Fowles, Nathan’s predecessor at the mission, is proof that Christianity doesn’t have to be a haughty rampage. He respects Africans enough to have married one, and his religion is a playful, elastic one built around love and working alongside creation.

- The King James Bible (plus Apocrypha, for which Nathan harbors a strange fondness) provides much of the book’s language and imagery, as well as the section headings. Many of these references come to have (sometimes mocking) relevance. Kingsolver also makes reference to classics of Africa-set fiction, like Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

- Africa is a place of many threats – malaria and dysentery, snakes in the chicken house, swarms of ants that eat everything in their path, corruption, political coups and assassinations – not least the risk of inadvertently causing grave cultural offense.

- The backdrop of the Congo’s history, especially the declaration of independence in 1960 and the U.S.-led “replacement” (by assassination) of its first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, with the dictator Mobutu, is thorough but subtle, such that minimal to no Googling is required to understand the context. (Only in one place, when Leah and Rachel are arguing as adults, does Kingsolver resort to lecturing on politics through dialogue, as she does so noticeably in Unsheltered.)

- Names are significant, as are their changes. With the end of colonialism Congo becomes Zaire and all its cities and landmarks are renamed, but the change seems purely symbolic. The characters take on different names in the course of the book, too, through nicknames, marriage or education. Many African words are so similar to each other that a minor mispronunciation by a Westerner changes the meaning entirely, making for jokes or irony. And the family’s surname is surely no coincidence: we are invited to question the price they have paid by coming to Africa.

- We follow the sisters decades into the future. “Africa has a thousand ways to get under your skin,” Leah writes; “we’ve all ended up giving up body and soul to Africa, one way or another.” Three of the four end up staying there permanently, but disperse into different destinies that seem to fit their characters. Even those Prices who return to the USA will never outrun the shadow the Congo has left on their lives.

What an amazing novel about the ways that right and wrong, truth and pain get muddied together. Some characters are able to acknowledge their mistakes and move on, while others never can. As Adah concludes, “We are the balance of our damage and our transgressions.”

What an amazing novel about the ways that right and wrong, truth and pain get muddied together. Some characters are able to acknowledge their mistakes and move on, while others never can. As Adah concludes, “We are the balance of our damage and our transgressions.”

I worried it would be a challenge to reread this in time to hand it over for my husband to take on his week-long field course in Devon, but it turned out to be a cinch. That’s the mark of success of a doorstopper for me: it’s so engrossing you hardly notice how long the book is. I think this will make for our best book club discussion yet. I can already think of a few questions to ask – Is it fair that Nathan never gets to tell his side of the story? Which of the five voices is your favorite? Who changes and who stays the same over the course of the book? – and I’m sure I’ll find many more resources online since this was an Oprah’s Book Club pick too.

English singer-songwriter Anne-Marie Sanderson’s excellent Book Songs, Volume 1 EP includes the song “Poisonwood.” The excerpted lyrics are below, with direct quotes from the text in bold.

Our Father speaks for all of us

Our Father knows what’s best for us as well

He planted a garden where poisonwood grew

He cut down the orchids cos none of us knew

that the seeds that filled his pockets

would grow and grow without stopping

his beans, his Kentucky Wonders

played their part in tearing us asunder.

Our mother suffered through all of this

Our mother carried the guilt

Carry us, marry us, ferry us, bury us

Carry us, bury us with the poisonwood.

Page count: 615

My rating: