Four Recommended May Releases

Here are four enjoyable books due out next month that I was lucky enough to read early. The first two are memoirs, the third is an audacious poetry book by an author new to me, and the last is the sophomore novel from an author I’ve loved before. I’ve pulled 250-word extracts from my full reviews and hope you’ll be tempted by one or more of these.

Last Things: A Graphic Memoir of Loss and Love by Marissa Moss

(Coming from Conari Press on May 1st [USA]; June 8th in UK)

“You’re not aware of last things,” Moss, a children’s book author/illustrator, writes in this wrenching memoir of losing her husband to ALS. We look forward to and celebrate all of life’s firsts, but we never know until afterwards when we’ve experienced a last. The author’s husband, Harvey Stahl, was a medieval art historian working on a book about Louis IX’s prayer book. ALS is always a devastating diagnosis, but Harvey had the particularly severe bulbar variety, and his lungs were quick to succumb. His battery-powered ventilator led to many scares – one time Moss had to plug him into the wall at a gas station and rush home for a spare battery – and he also underwent an emergency tracheotomy surgery.

“You’re not aware of last things,” Moss, a children’s book author/illustrator, writes in this wrenching memoir of losing her husband to ALS. We look forward to and celebrate all of life’s firsts, but we never know until afterwards when we’ve experienced a last. The author’s husband, Harvey Stahl, was a medieval art historian working on a book about Louis IX’s prayer book. ALS is always a devastating diagnosis, but Harvey had the particularly severe bulbar variety, and his lungs were quick to succumb. His battery-powered ventilator led to many scares – one time Moss had to plug him into the wall at a gas station and rush home for a spare battery – and he also underwent an emergency tracheotomy surgery.

This is an emotionally draining read. It’s distressing to see how, instead of drawing closer and relying on each other, Marisa and Harvey drifted apart. Harvey pushed everyone away and focused on finishing his book and returning to his academic duties. He refused to accept his limitations and resisted necessary medical interventions. Meanwhile, Moss struggled with the unwanted role of caregiver while trying not to neglect her children and her own career.

I’ve read several nonfiction books about ALS now. Compared to the other two, Moss gets the tone just right. She’s a reliable witness to a medical and bureaucratic nightmare. At the distance of years, though, she writes about the experience without bitterness. I can see this graphic novel being especially helpful to older teens with a terminally ill parent.

My rating:

My Life with Bob: Flawed Heroine Keeps Book of Books, Plot Ensues by Pamela Paul

(Coming from Henry Holt on May 2nd [USA]; June 13th in UK)

I hold books about books to high standards and won’t stand for the slightest hint of plot summary, filler or spoilers. It’s all too easy for an author to concentrate on certain, often obscure books that mean a lot to him/her, dissecting the plots without conveying a sense of the wider appeal. The trick is to find the universal in the particular, and vice versa.

I hold books about books to high standards and won’t stand for the slightest hint of plot summary, filler or spoilers. It’s all too easy for an author to concentrate on certain, often obscure books that mean a lot to him/her, dissecting the plots without conveying a sense of the wider appeal. The trick is to find the universal in the particular, and vice versa.

Pamela Paul, editor of the New York Times Book Review, does this absolutely perfectly. In 1988, as a high school junior, she started keeping track of her reading in a simple notebook she dubbed “Bob,” her Book of Books. In this memoir she delves into Bob to explain how her reading both reflected and shaped her character. The focus is unfailingly on books’ interplay with her life, such that each one mentioned more than earns its place.

A page from my 2007 reading diary. Lots of mid-faith-crisis religion titles there. Starting in 2009, I think, I’ve kept this information in an annual computer file instead.

So whether she was hoarding castoffs from her bookstore job, obsessing about ticking off everything in the Norton Anthology, despairing that she’d run out of reading material in a remote yurt in China, or fretting that her husband took a fundamentally different approach to the works of Thomas Mann, Paul always looks beyond the books themselves to interrogate what they say about herself.

This is the sort of book I wish I had written. If you have even the slightest fondness for books about books, you won’t want to miss this one. I’ve found a new favorite bibliomemoir, and an early entry on the Best of 2017 list.

My rating:

Nature Poem by Tommy Pico

(Coming on May 9th from Tin House Books)

Tommy “Teebs” Pico is a Native American from the Kumeyaay nation and grew up on the Viejas Indian reservation. This funny, sexy, politically aware multi-part poem was written as a collective rebuttal to the kind of line he often gets in gay bars, something along the lines of ‘oh, you’re an Indian poet, so you must write about nature?’ Au contraire: Pico’s comfort zone is the urban, the pop cultural, and the technologically up-to-date – his poems are full of textspeak (“yr,” “bc” for because, “rn” for right now, “NDN” for Indian), an affectation that would ordinarily bother me but that I tolerated here because of Pico’s irrepressible sass: “I wd give a wedgie to a sacred mountain and gladly piss on the grass of / the park of poetic form / while no one’s lookin.”

Tommy “Teebs” Pico is a Native American from the Kumeyaay nation and grew up on the Viejas Indian reservation. This funny, sexy, politically aware multi-part poem was written as a collective rebuttal to the kind of line he often gets in gay bars, something along the lines of ‘oh, you’re an Indian poet, so you must write about nature?’ Au contraire: Pico’s comfort zone is the urban, the pop cultural, and the technologically up-to-date – his poems are full of textspeak (“yr,” “bc” for because, “rn” for right now, “NDN” for Indian), an affectation that would ordinarily bother me but that I tolerated here because of Pico’s irrepressible sass: “I wd give a wedgie to a sacred mountain and gladly piss on the grass of / the park of poetic form / while no one’s lookin.”

Some more favorite lines:

“How do statues become more galvanizing than refugees / is not something I wd include in a nature poem.”

“Knowing the moon is inescapable tonight / and the tuft of yr chest against my shoulder blades— / This is a kind of nature I would write a poem about.”

“I can’t write a nature poem bc English is some Stockholm shit, makes me complicit in my tribe’s erasure”

“It’s hard to unhook the heavy marble Nature from the chain around yr neck / when history is stolen like water. // Reclamation suggests social / capital”

My rating:

The Awkward Age by Francesca Segal

(Coming on May 4th from Chatto & Windus [UK] and May 16th from Riverhead Books [USA])

I adored Segal’s first novel, The Innocents, a sophisticated remake of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence set in a contemporary Jewish community in London. I wasn’t as fond of this second book, but in her study of an unusual blended family the characterization is nearly as strong as in her debut. Julia Alden lost her husband to cancer five years ago. A second chance at happiness came when James Fuller, a divorced American obstetrician, came to her for piano lessons. He soon moved into Julia and sixteen-year-old Gwen’s northwest London home, and his seventeen-year-old son, Nathan, away at boarding school, came on weekends.

I adored Segal’s first novel, The Innocents, a sophisticated remake of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence set in a contemporary Jewish community in London. I wasn’t as fond of this second book, but in her study of an unusual blended family the characterization is nearly as strong as in her debut. Julia Alden lost her husband to cancer five years ago. A second chance at happiness came when James Fuller, a divorced American obstetrician, came to her for piano lessons. He soon moved into Julia and sixteen-year-old Gwen’s northwest London home, and his seventeen-year-old son, Nathan, away at boarding school, came on weekends.

Julia is as ill at ease with Nathan as James is with Gwen, and the kids seem to hate each other. That is until, on a trip to Boston for Thanksgiving with James’s ex, Gwen and Nathan fall for each other. Awkward is one way of putting it. They’re not technically step-siblings as James and Julia aren’t married, but it doesn’t sit right with the adults, and it will have unexpected consequences.

The first third or so of the book was my favorite, comparable to Jonathan Safran Foer or Jonathan Franzen. Before long the romantic comedy atmosphere tips into YA melodrama, but for me the book was saved by a few things: a balance of generations, with Gwen’s grandparents a delightful background presence; the eye to the past, whether it be Gwen’s late father or the occasional Jewish ritual; the Anglo-American element; and a realistic ending.

My rating:

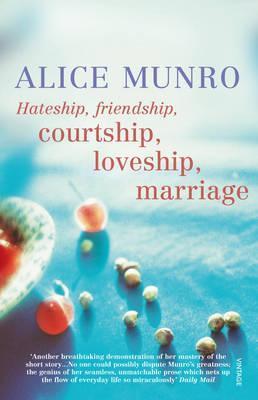

There are nine stories in the 320-page volume, so the average story here is 30–35 pages – a little longer than I tend to like, but it allows Munro to fill in enough character detail that these feel like miniature novels; they certainly have all the emotional complexity. Her material is small-town Ontario and the shifts and surprises in marriages and dysfunctional families.

There are nine stories in the 320-page volume, so the average story here is 30–35 pages – a little longer than I tend to like, but it allows Munro to fill in enough character detail that these feel like miniature novels; they certainly have all the emotional complexity. Her material is small-town Ontario and the shifts and surprises in marriages and dysfunctional families. Back in 2021, I read 14 of these 25 stories (reviewed

Back in 2021, I read 14 of these 25 stories (reviewed  Ulrich’s second collection contains 50 flash fiction pieces, most of which were first published in literary magazines. She often uses the first-person plural and especially the second person; both “we” and “you” are effective ways of implicating the reader in the action. Her work is on a speculative spectrum ranging from magic realism to horror. Some of the situations are simply bizarre – teenagers fall from the sky like rain; a woman falls in love with a giraffe; the mad scientist next door replaces a girl’s body parts with robotic ones – while others are close enough to the real world to be terrifying. The dialogue is all in italics. Some images recur later in the collection: metamorphoses, spontaneous combustion. Adolescent girls and animals are omnipresent. At a certain point this started to feel repetitive and overlong, but in general I appreciated the inventiveness.

Ulrich’s second collection contains 50 flash fiction pieces, most of which were first published in literary magazines. She often uses the first-person plural and especially the second person; both “we” and “you” are effective ways of implicating the reader in the action. Her work is on a speculative spectrum ranging from magic realism to horror. Some of the situations are simply bizarre – teenagers fall from the sky like rain; a woman falls in love with a giraffe; the mad scientist next door replaces a girl’s body parts with robotic ones – while others are close enough to the real world to be terrifying. The dialogue is all in italics. Some images recur later in the collection: metamorphoses, spontaneous combustion. Adolescent girls and animals are omnipresent. At a certain point this started to feel repetitive and overlong, but in general I appreciated the inventiveness.  I also read the first two stories in The Best Short Stories 2023: The O. Henry Prize Winners, edited by Lauren Groff. If these selections by Ling Ma and Catherine Lacey are anything to go by, Groff’s taste is for gently magical stories where hints of the absurd or explained enter into everyday life. Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal. I’ll try to remember to occasionally open the book on my e-reader to get through the rest.

I also read the first two stories in The Best Short Stories 2023: The O. Henry Prize Winners, edited by Lauren Groff. If these selections by Ling Ma and Catherine Lacey are anything to go by, Groff’s taste is for gently magical stories where hints of the absurd or explained enter into everyday life. Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal. I’ll try to remember to occasionally open the book on my e-reader to get through the rest.