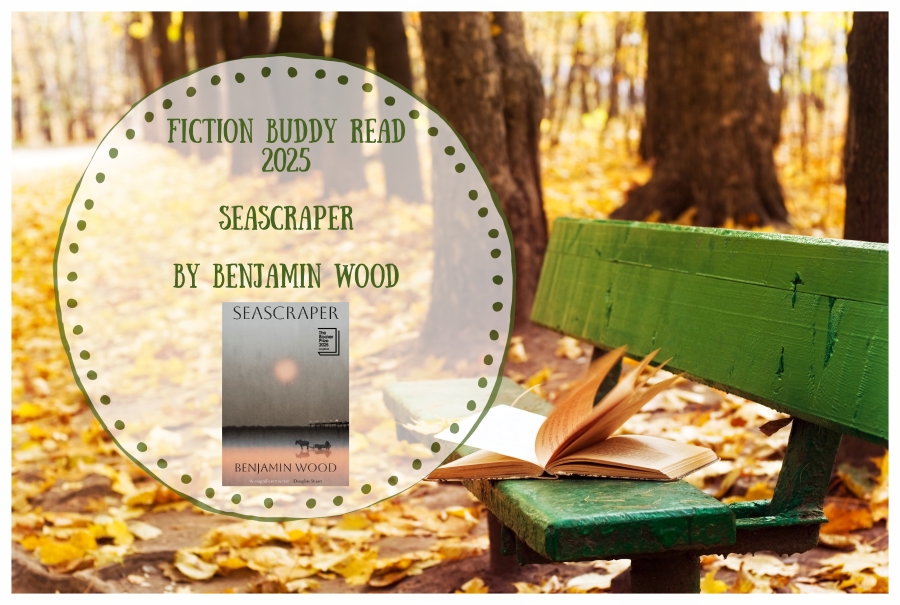

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood (#NovNov25 Buddy Read)

Seascraper is set in what appears to be the early 1960s yet could easily be a century earlier because of the protagonist’s low-tech career. Thomas Flett lives with his mother in fictional Longferry in northwest England and carries on his grandfather’s tradition of fishing with a horse and cart. Each day he trawls the seabed for shrimp – sometimes twice a day when the tide allows – and sells his catch to local restaurants. At around 20 years old, Thomas still lives with his mother, who is disabled by obesity and chronic pain. He’s the sole breadwinner in the household and there’s an unusual dynamic between them in that his mother isn’t all that many years older, having fallen pregnant by a teacher while she was still in school.

Their life is just a mindless trudge of work with cosy patterns of behaviour in between … He wants to wake up every morning with a better purpose.

It’s a humdrum, hardscrabble existence, and Thomas longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or a chance encounter with an American filmmaker. Edgar Acheson is working on a big-screen adaptation of a novel; to save money, it will be filmed here in Merseyside rather than in coastal Maine where it’s set. One day he turns up at the house asking Thomas to be his guide to the sands. Thomas reluctantly agrees to take Edgar out one evening, even though it will mean missing out on an open mic night. They nearly get lost in the fog and the cart starts to sink into quicksand. What follows is mysterious, almost like a hallucination sequence. When Thomas makes it back home safely, he writes an autobiographical song, “Seascraper” (you can listen to a recording on Wood’s website).

After this one pivotal and surprising day, Thomas’s fortunes might just change. This atmospheric novella contrasts subsistence living with creative fulfillment. There is the bitterness of crushed dreams but also a glimmer of hope. Its The Old Man and the Sea-type setup emphasizes questions of solitude, obsession and masculinity. Thomas wishes he had a father in his life; Edgar, even in so short a time frame, acts as a sort of father figure for him. And Edgar is a father himself – he shows Thomas a photo of his daughter. We are invited to ponder what makes a good father and what the absence of one means at different stages in life. Mental and physical health are also crucial considerations for the characters.

That Wood packs all of this into a compact circadian narrative is impressive. My admiration never crossed into warmth, however. I’ve read four of Wood’s five novels and still love his debut, The Bellwether Revivals, most, followed by his second, The Ecliptic. I’ve also read The Young Accomplice, which I didn’t care for as much, so I’m only missing out on A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better now. Wood’s plot and character work is always at a high standard, but his books are so different from each other that I have no clear sense of him as a novelist. Still, I’m pleased that the Booker longlisting has introduced him to many new readers.

Also reviewed by:

Annabel (AnnaBookBel)

Anne (My Head Is Full of Books)

Brona (This Reading Life)

Cathy (746 Books)

Davida (The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog)

Eric (Lonesome Reader)

Jane (Just Reading a Book)

Helen (She Reads Novels)

Kate (Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Kay (What? Me Read?)

Nancy (The Literate Quilter)

Rachel (Yarra Book Club)

Susan (A life in books)

Check out this written interview with Wood (and this video one with Eric of Lonesome Reader) as well as a Q&A on the Booker Prize website in which Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote the book.

(Public library)

[163 pages]

![]()

Love Your Library, October 2025

Thanks, as always, to Eleanor and Skai for posting about their recent library reading!

Library borrowing is often the only thing that allows me to follow literary prizes. My library system always acquires at least the entire shortlist for most major UK prizes; sometimes the longlist as well. It would be fair to say that I’ve not engaged with what I’ve read from the Booker Prize shortlist this year. I half-heartedly skimmed two novels (Choi and Miller) and swiftly DNFed another (Markovits; see below). The Desai isn’t going to happen any time soon due to the length, and I haven’t enjoyed Kitamura enough in the past to try her again. David Szalay is my last great hope! I remember liking his All that Man Is, so when I pick up Flesh from the library tomorrow I’ll be hoping that it jumps out at me as a potential winner.

My library use over the last month:

(links are to books not already reviewed on the blog; some reviews are still to come)

READ

- New Cemetery by Simon Armitage

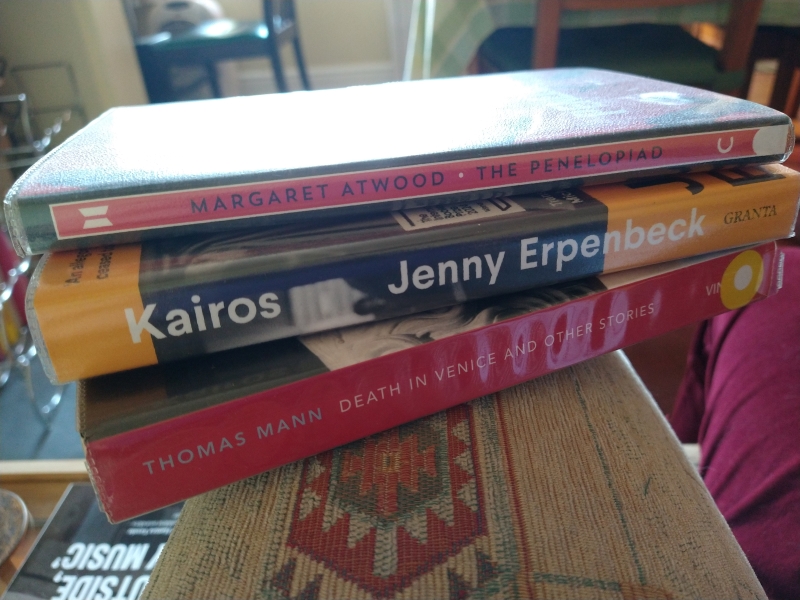

- The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood

- Cathedral by Raymond Carver

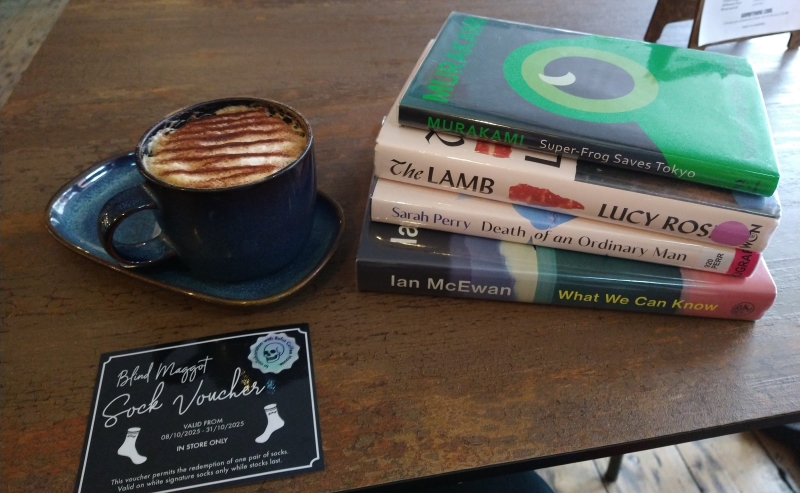

- Dim Sum Palace by X. Fang

- The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness

- Endling by Maria Reva

- The Doctor Stories by William Carlos Williams

Naughty photo bomber on the dining table!

SKIMMED

- Flashlight by Susan Choi

- All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert

- The Haunted Wood: A History of Childhood Reading by Sam Leith

- Buckeye by Patrick Ryan

CURRENTLY READING

- The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier

- Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck

- Emil and the Detectives by Erich Kästner

- Misery by Stephen King

- Of Thorn & Briar: A Year with the West Country Hedgelayer by Paul Lamb

- Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde

- Red Pockets: An Offering by Alice Mah

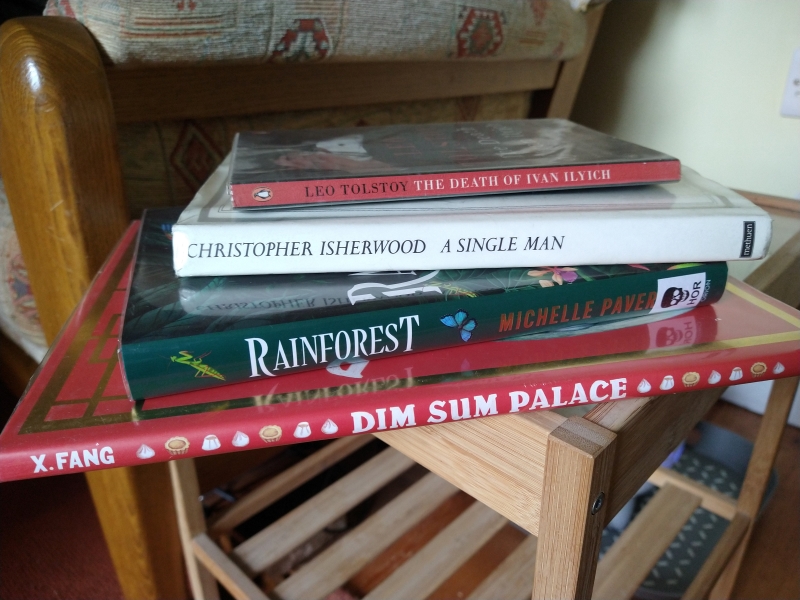

- Rainforest by Michelle Paver

- Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- A Single Man by Christopher Isherwood

- Death in Venice and Other Stories by Thomas Mann

- Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami

- The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoy

ON HOLD, TO BE COLLECTED

- The Eights by Joanna Miller

- Flesh by David Szalay

- Notes on Infinity by Austin Taylor

- Lone Wolf: Walking the Faultlines of Europe by Adam Weymouth

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood

- It’s Not a Bloody Trend: Understanding Life as an ADHD Adult by Kat Brown

- Look Closer: How to Get More out of Reading by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

- Honour & Other People’s Children by Helen Garner

- Snegurochka by Judith Heneghan

- The Perimenopause Survival Guide: A Feel-Like-Yourself-Again Roadmap for Every Woman over 35 by Heather Hirsch

- Queen Esther by John Irving

- The Matchbox Girl by Alice Jolly

- Heart the Lover by Lily King

- Night Life: Walking Britain’s Wild Landscapes after Dark by John Lewis-Stempel

- The Shapeshifter’s Daughter by Sally Magnusson

- Winter by Val McDermid

Library pick-ups on my birthday; I perused them over a cappuccino at my favourite local coffeehouse. Also got a voucher for a free pair of socks (which I gave to my husband).

RETURNED UNREAD

- The Two Roberts by Damian Barr – Lost immediate interest.

- Opt Out by Carolina Setterwall – Lost immediate interest.

- Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth – Keeps being requested off me.

- Night Side of the River by Jeanette Winterson – I was put off by the endless introduction about the history of ghost stories, and at a glance none of the stories themselves jumped out at me.

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- The Ghost Cat by Alex Howard – Great premise but iffy writing/editing, including lots of “reigns”-instead-of-reins nonsense. I read 40-some pages.

- The Rest of Our Lives by Benjamin Markovits – THIS is one of the six best books of the past year!? I thought I’d try Markovits again after the lacklustre A Weekend in New York but I barely made it past page 10. What a boring voice!

- What We Can Know by Ian McEwan – I was tickled that the protagonist shares my birthday, but not at all drawn in. I read 20-some pages.

- The Lamb by Lucy Rose – The vampire novel I have on the go is enough for me for R.I.P. without cannibalism added on. I glanced at the first few pages.

- A Long Winter by Colm Tóibín – Jumping on that Claire Keegan stand-alone-story bandwagon. Except this story of an alcoholic mother and soldier brother was deathly dull. I read 30-some pages (in a small hardback with some supplementary material this is stretched out to 130+).

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Orbital by Samantha Harvey (#NovNov24 Buddy Read)

Orbital is a circadian narrative, but its one day contains multitudes. Every 90 minutes, a spacecraft completes an orbit of the Earth; the 24 hours the astronauts experience equate to 16 days. And in the same way, this Booker Prize-shortlisted novella contains much more than seems possible for its page length. It plays with scale, zooming from the cosmic down to the human, then back. The situation is simultaneously extraordinary and routine:

Six of them in a great H of metal hanging above the earth. They turn head on heel, four astronauts (American, Japanese, British, Italian) and two cosmonauts (Russian, Russian); two women, four men, one space station made up of seventeen connecting modules, seventeen and a half thousand miles an hour. They are the latest six of many, nothing unusual about this any more[.]

We see these characters – Anton, Roman, Nell, Chie, Shaun, and Pietro – going about daily life as they approach the moon: taking readings, recording data on their health and lab mice’s, exercising, conversing over packaged foods, watching a film, then getting back into the sleeping bags where they started the day. Apart from occasional messages from family, theirs is a completely separate, closed-off existence. Is it magical or claustrophobic? Godlike, they cast benevolent eyes over a whole planet, yet their thoughts are always with the two or three individual humans who mean most to them. A wife, a daughter, a mother who has just died.

Apart from the bereaved astronaut – the one I sympathized with most – I didn’t get a strong sense of the characters as individuals. This may have been deliberate on Harvey’s part, to emphasize how reliant the six are on each other for survival: “we are one. Everything we have up here is only what we reuse and share. … We drink each other’s recycled urine. We breathe each other’s recycled air.” That collectivity and the overt messaging give the book the air of a parable.

Maybe it’s hard to shift from thinking your planet is safe at the centre of it all to knowing in fact it’s a planet of normalish size and normalish mass rotating about an average star in a solar system of average everything in a galaxy of innumerably many, and that the whole thing is going to explode or collapse.

Our lives here are inexpressibly trivial and momentous at once … Both repetitive and unprecedented. We matter greatly and not at all.

Gaining perspective on humankind is always valuable. There is also a strong environmental warning here. “The planet is shaped by the sheer amazing force of human want, which has changed everything, the forests, the poles, the reservoirs, the glaciers, the rivers, the seas, the mountains, the coastlines, the skies”. The astronauts observe climate breakdown firsthand through the inexorable development of a super-typhoon over the Philippines.

There are some stunning lyrical passages (“We exist now in a fleeting bloom of life and knowing, one finger-snap of frantic being … This summery burst of life is more bomb than bud. These fecund times are moving fast”), but Harvey sometimes gets carried away with the sound of words or the sweep of imagery, such that the style threatens to overwhelm the import. This was especially true of the last line. At times, I felt I was watching a BBC nature documentary full of soaring panoramas and time-lapse shots, all choreographed to an ethereal Sigur Rós soundtrack. Am I a cynic for saying so? I confess I don’t think this will win the Booker. But for the most part, I was entranced; grateful for the peek at the immensity of space, the wonder of Earth, and the fragility of human beings. (Public library)

[136 pages]

Mini playlist:

- “Space Walk” by Lemon Jelly

- “Spacewalk” by Bell X1

- “Magic” & “Wonder” by Gungor

- “Hoppípolla” by Sigur Rós

- “Little Astronaut” by Jim Molyneux and Spell Songs

Never fear, others have been more enthusiastic!

Reviewed for this challenge so far by:

A Bag Full of Stories (Susana)

Book Chatter (Tina)

Books Are My Favourite and Best (Kate)

Buried in Print (Marcie)

Calmgrove (Chris)

The Intrepid Angeleno (Jinjer)

My Head Is Full of Books (Anne)

Words and Peace (Emma)

Reviewed earlier by other participants and friends:

Love Your Library, July 2024

Thanks so much to Eleanor, Laura and Marcie for posting about their recent library reads! It’s been a light library reading month for me, but I’m awaiting many holds of recent releases, including a coincidental gardening-themed trio that I fancy reviewing together if the timing works out.

Marcie also gifted me a New York Times article so that I could go through their list of the 100 Best Books of the 21st Century so far and see how many I have read. The answer is 53 (+ 6 DNFs), with another 23 on my TBR. I pulled some awardees off my shelves and might try reading them later this year (below right) – let me know if you’d like to buddy read any of them with me. I was pleased to see that the article first encouraged readers to reserve books from their local library before giving links to places where they can be bought.

It was fun to find libraries mentioned in a couple of library books I’ve been reading recently:

- Thanked in the Acknowledgements to Soldier Sailor by Claire Kilroy: “The librarians of Howth and Baldoyle who are part of the village that raises the child”.

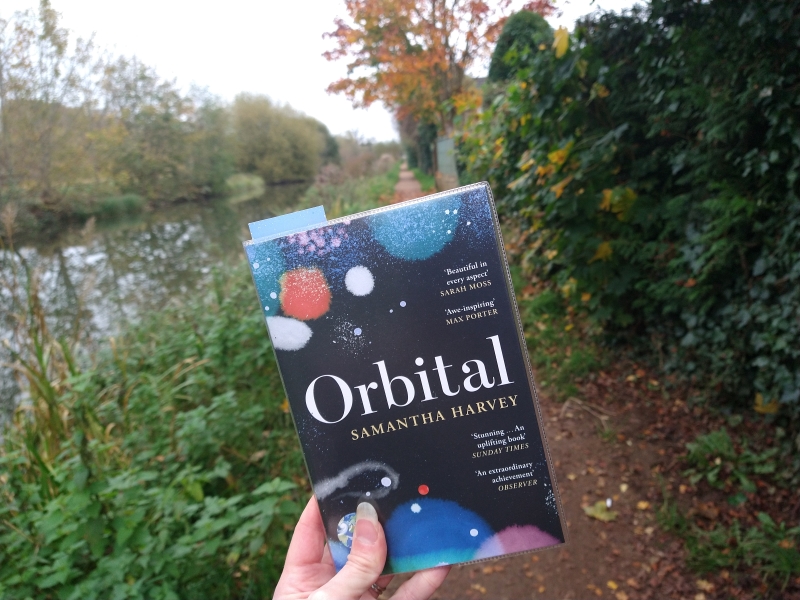

- From Late Light by Michael Malay:

[When I was] a boy in Australia, my mother often took me to a library near our house, a small concrete building that stood across the road from a chicken shop and a video rental store. … the front door was slightly warped, making it difficult to pull open, while the carpet had been worn bare by years of footfall – and yet, to my fourteen- or fifteen-year-old self, it was a kind of palace. I would go there once or twice a week, roam the shelves on my own, gather all the books that appealed to me, and then take home as many titles as our library account would allow. I don’t think the books I chose were ever to my mother’s taste – at that time, I was obsessed with comics and fantasy novels – but she encouraged my enthusiasm anyway. … looking back now, I see that these books did other things for me – that they fed my curiosity, made time move in different ways, and opened up portals to other worlds. In all those years, I can’t remember my mother ever encouraging me to read more ‘serious’ or ‘literary’ books, and I continue to love her for that.

[When I was] a boy in Australia, my mother often took me to a library near our house, a small concrete building that stood across the road from a chicken shop and a video rental store. … the front door was slightly warped, making it difficult to pull open, while the carpet had been worn bare by years of footfall – and yet, to my fourteen- or fifteen-year-old self, it was a kind of palace. I would go there once or twice a week, roam the shelves on my own, gather all the books that appealed to me, and then take home as many titles as our library account would allow. I don’t think the books I chose were ever to my mother’s taste – at that time, I was obsessed with comics and fantasy novels – but she encouraged my enthusiasm anyway. … looking back now, I see that these books did other things for me – that they fed my curiosity, made time move in different ways, and opened up portals to other worlds. In all those years, I can’t remember my mother ever encouraging me to read more ‘serious’ or ‘literary’ books, and I continue to love her for that.

I’ve seen this Peanuts comic before and I love it. Isn’t library borrowing a brilliant concept?! All the more astounding when you step back to think about it anew. This was shared on Facebook by the library in the village where we go to church. Threatened with closure, it went independent. It has a building on peppercorn rent from the council and is run by volunteers. I don’t borrow books there because I can rarely visit during their limited opening hours (and I have plenty of other library books on my plate), but I do try to get to their book sales at least once or twice a year – particularly useful for stocking up on 3/£1 books for the book swapping game I run at our book club holiday social each year.

Tomorrow at 2 p.m. (if you’re in the UK, that is), the Booker Prize longlist will be announced. No doubt I’ll be baffled at all the books I’ve never heard of, or read. It happens every year. Perhaps I’ll be tempted enough by two or three nominees to place library holds on them right away.

My library use over the last month:

READ

- Fortunately, The Milk… by Neil Gaiman

SKIMMED

SKIMMED

- Rites of Passage: Death and Mourning in Victorian Britain by Judith Flanders

CURRENTLY READING

The Cove: A Cornish Haunting by Beth Lynch (I enjoyed her previous memoir)

The Cove: A Cornish Haunting by Beth Lynch (I enjoyed her previous memoir)- Groundbreakers: The Return of Britain’s Wild Boar by Chantal Lyons (Wainwright Prize longlist)

- Late Light: Finding Home in the West Country by Michael Malay (Wainwright Prize longlist)

- The Song of the Whole Wide World: On Motherhood, Grief, and Poetry by Tamarin Norwood (resuming this after it went out to fulfil an interlibrary loan)

CURRENTLY READING-ish (more accurately, set aside temporarily)

- Death Valley by Melissa Broder

- The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo

- King: A Life by Jonathan Eig

- Mother’s Boy by Patrick Gale

- Learning to Think: A Memoir about Faith, Demons, and the Courage to Ask Questions by Tracy King

- Unearthing: A Story of Tangled Love and Family Secrets by Kyo Maclear

- Late Light: Finding Home in the West Country by Michael Malay

- Mrs Gulliver by Valerie Martin

- After Dark by Haruki Murakami

- Excellent Women by Barbara Pym

- Stowaway: The Disreputable Exploits of the Rat by Joe Shute

- Mrs Hemingway by Naomi Wood

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

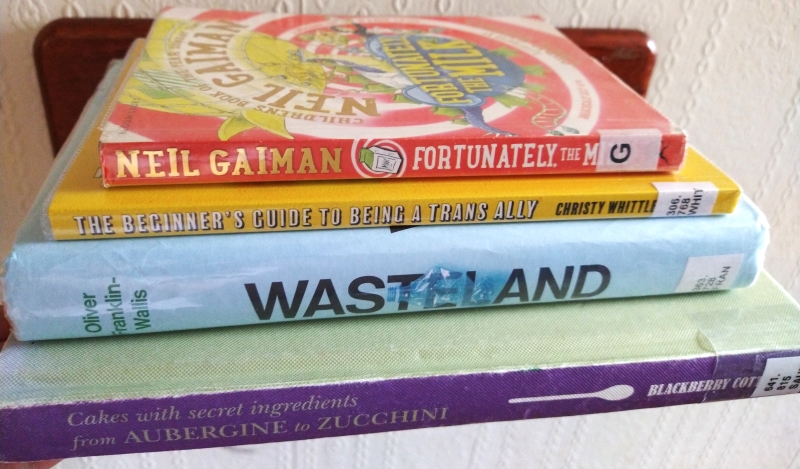

- Wasteland: The Dirty Truth about What We Throw Away, Where It Goes, and Why It Matters by Oliver Franklin-Wallis

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Private Rites by Julia Armfield (I read 43% on Kindle and stalled so I’ll try again in print)

- One Garden against the World: In Search of Hope in a Changing Climate by Kate Bradbury

- The Painter’s Daughters by Emily Howes

- The Garden against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing

- The Accidental Garden: The Plot Thickens by Richard Mabey

- The Burial Plot by Elizabeth Macneal

- This Is My Sea by Miriam Mulcahy

- The Echoes by Evie Wyld

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- Parade by Rachel Cusk

- Nature’s Ghosts: A History – and Future – of the Natural World by Sophie Yeo

RETURNED UNREAD

- Hungry Ghosts by Kevin Jared Hosein – A glance at the first few pages was enough to put me off.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

This meme runs every month, on the final Monday. Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Reading Ireland Month, Part II: Hughes, Kennedy, Murray

My second contribution to Reading Ireland Month after a first batch that included poetry and a novel.

Today I have a poetry collection based around science and travel, and two multi-award-winning novels, one set in the thick of the Troubles in Belfast and another about the crumbling of an ordinary suburban family.

Gathering Evidence by Caoilinn Hughes (2014)

I bought this in the same order as Patricia Lockwood’s poetry collection, thinking a segue to another genre within an author’s oeuvre (I’d enjoyed Hughes’s 2018 debut novel, Orchid & the Wasp) might be a clever strategy. That worked out with Lockwood, but not as well here. A collection about scientific discoveries and medical advances seemed likely to be up my street. “The Moon Should Be Turned” is about the future of the HeLa cells harvested from Henrietta Lacks; poems are dedicated to the Curies and Johannes Kepler and one has Fermi as a main character. Russian nuclear force is a background menace. There are also some poems about growing up in Dublin and travels in the Andes. “Vagabond Monologue” stood out for its voice, “Marbles” for its description of childhood booty: “A netted bag of green glass marbles with aquamarine swirls / deep in the otherworld of spherical transparency (simultaneous opacity) / was the first thing I ever stole when I was three and far from the last.” Elsewhere, though, I found the precision vocabulary austere and offputting. (New purchase with Amazon voucher)

I bought this in the same order as Patricia Lockwood’s poetry collection, thinking a segue to another genre within an author’s oeuvre (I’d enjoyed Hughes’s 2018 debut novel, Orchid & the Wasp) might be a clever strategy. That worked out with Lockwood, but not as well here. A collection about scientific discoveries and medical advances seemed likely to be up my street. “The Moon Should Be Turned” is about the future of the HeLa cells harvested from Henrietta Lacks; poems are dedicated to the Curies and Johannes Kepler and one has Fermi as a main character. Russian nuclear force is a background menace. There are also some poems about growing up in Dublin and travels in the Andes. “Vagabond Monologue” stood out for its voice, “Marbles” for its description of childhood booty: “A netted bag of green glass marbles with aquamarine swirls / deep in the otherworld of spherical transparency (simultaneous opacity) / was the first thing I ever stole when I was three and far from the last.” Elsewhere, though, I found the precision vocabulary austere and offputting. (New purchase with Amazon voucher) ![]()

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (2022)

Despite its many accolades, not least a shortlisting for the Women’s Prize, I couldn’t summon much enthusiasm for reading a novel about the Troubles. I don’t know why I tend to avoid this topic; perhaps it’s the insidiousness of fighting that’s not part of a war somewhere else, but ongoing domestic terrorism instead. Combine that with an affair – Cushla is a 24-year-old schoolteacher who starts sleeping with a middle-aged, married barrister she meets in her family’s pub – and it sounded like a tired, ordinary plot. But after this won last year’s McKitterick Prize (for debut authors over 40) and I was sent the whole shortlist in thanks for being a manuscript judge, I thought I should get over myself and give it a try.

Little surprise that Kennedy’s writing – compassionate, direct, heart-rending – is what sets the book apart. With no speech marks, radio reports of everyday atrocities blend in with thoughts and conversations. We meet and develop fondness for characters across classes and the Catholic–Protestant divide: Cushla’s favourite pupil, Davy, whose father was assaulted in the street; her alcoholic mother, Gina, who knows more than she lets on, despite her inebriation; Gerry, a colleague who takes Cushla on friend dates and covers for her when she goes to see Michael. An Irish language learning circle introduces the 1970s bourgeoisie with their dinner parties and opinions.

Little surprise that Kennedy’s writing – compassionate, direct, heart-rending – is what sets the book apart. With no speech marks, radio reports of everyday atrocities blend in with thoughts and conversations. We meet and develop fondness for characters across classes and the Catholic–Protestant divide: Cushla’s favourite pupil, Davy, whose father was assaulted in the street; her alcoholic mother, Gina, who knows more than she lets on, despite her inebriation; Gerry, a colleague who takes Cushla on friend dates and covers for her when she goes to see Michael. An Irish language learning circle introduces the 1970s bourgeoisie with their dinner parties and opinions.

This doesn’t read like a first novel at all, with each character fully realized and the plot so carefully constructed that I was as shocked as Cushla by a revelation four-fifths of the way through. Desire is bound up with guilt; can anyone ever be happy when violence is so ubiquitous and random? “Booby trap. Incendiary device. Gelignite. Nitroglycerine. Petrol bomb. Rubber bullets. Saracen. Internment. The Special Powers Act. Vanguard. The vocabulary of a seven-year-old child now.” But a brief framing episode set in 2015 gives hope of life beyond seemingly inescapable tragedy. (Free from the Society of Authors) ![]()

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray (2023)

“The trouble is coming from inside; from his family. And unless something happens to stop it, it will keep billowing out, worse and worse”

Another great Irish novel I nearly missed out on, despite it being shortlisted for the Booker Prize and Writers’ Prize and winning the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize, this one because I was daunted by its doorstopper proportions. I’d gotten it in mind that it was all about money: Dickie Barnes’s car dealership is foundering and the straitened circumstances affect his whole family (wife Imelda, teenage daughter Cass, adolescent son PJ). A belated post-financial crash novel? Again, it sounded tired, maybe clichéd.

But actually, this turned out to be just the kind of wry, multi-perspective dysfunctional family novel that I love, such that I was mostly willing to excuse a baggy midsection. Murray opens with long sections of close third person focusing on each member of the Barnes family in turn. Cass is obsessed with sad-girl poetry and her best friend Elaine, but self-destructive habits threaten her university career before it’s begun. PJ is better at making friends through online gaming than in real life because of his family’s plunging reputation, so concocts a plan to run away to Dublin. Imelda is flirting with Big Mike, who’s taking over the dealership, but holds out hope that Dickie’s wealthy father will bail them out. Dickie, under the influence of a weird handyman named Victor, has become fixated on eradicating grey squirrels and building a bunker to keep his family safe.

But actually, this turned out to be just the kind of wry, multi-perspective dysfunctional family novel that I love, such that I was mostly willing to excuse a baggy midsection. Murray opens with long sections of close third person focusing on each member of the Barnes family in turn. Cass is obsessed with sad-girl poetry and her best friend Elaine, but self-destructive habits threaten her university career before it’s begun. PJ is better at making friends through online gaming than in real life because of his family’s plunging reputation, so concocts a plan to run away to Dublin. Imelda is flirting with Big Mike, who’s taking over the dealership, but holds out hope that Dickie’s wealthy father will bail them out. Dickie, under the influence of a weird handyman named Victor, has become fixated on eradicating grey squirrels and building a bunker to keep his family safe.

There are no speech marks throughout, and virtually no punctuation in Imelda’s sections. There are otherwise no clever tricks to distinguish the points-of-view, though. The voice is consistent. Murray doesn’t have to strain to sound like a teenage girl; he fully and convincingly inhabits each character (even some additional ones towards the end). I particularly liked the final “Age of Loneliness” section, which starts rotating between the perspectives more quickly, each one now in the second person. It all builds towards a truly thrilling yet inconclusive ending. I could imagine this as a TV miniseries for sure.

SPOILERS, if you’re worried about that sort of thing:

It was all the details I didn’t pick up from my pre-reading about The Bee Sting that made it so intricate and rewarding. Imelda’s awful upbringing in macho poverty and how it seemed that Rose, then Frank, might save her. The cruelty of Frank’s accidental death and the way that, for both Imelda and Dickie, being together seemed like the only way of getting over him, even if Imelda was marrying the ‘wrong’ brother. The recurrence of same-sex attraction for Dickie, then Cass. The irony of the bee sting that never was.

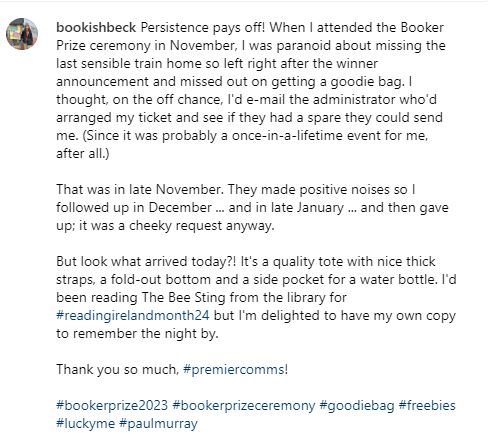

BUT. Yes, it’s too long, particularly Imelda’s central section. I had to start skimming to have any hope of making it through. Trim the whole thing by 200 pages and then we’re really talking. But I will certainly read Murray again, and most likely will revisit this book in the future to give it the attention it deserves. I read it from the library’s Bestsellers collection; the story of how I own a copy as of this week is a long one…

(Public library; free from the Booker Prize/Premier Comms) ![]()

I’ll be catching up on reviewing March releases in early April.

Happy Easter to those who celebrate!

Some 2023 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Shortest book read this year: Pitch Black by Youme Landowne and Anthony Horton (40 pages)

Authors I read the most by this year: Margaret Atwood, Deborah Levy and Brian Turner (3 books each); Amy Bloom, Simone de Beauvoir, Tove Jansson, John Lewis-Stempel, W. Somerset Maugham, L.M. Montgomery and Maggie O’Farrell (2 books each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Setting aside the ubiquitous Penguin and its many imprints) Carcanet (11 books) and Picador/Pan Macmillan (also 11), followed by Canongate (7).

My top author discoveries of the year: Michelle Huneven and Julie Marie Wade

My proudest bookish accomplishment: Helping to launch the Little Free Library in my neighbourhood in May, and curating it through the rest of the year (nearly daily tidying; occasional culling; requesting book donations)

Most pinching-myself bookish moments: Attending the Booker Prize ceremony; interviewing Lydia Davis and Anne Enright over e-mail; singing carols after-hours at Shakespeare and Company in Paris

Books that made me laugh: Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson, The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt, two by Katherine Heiny, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

Books that made me cry: A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney, Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout, Family Meal by Bryan Washington

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Best book club selections: By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah and The Woman in Black by Susan Hill

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

Shortest book title encountered: Lo (the poetry collection by Melissa Crowe), followed by Bear, Dirt, Milk and They

Best 2023 book titles: These Envoys of Beauty and You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore (shame the contents didn’t live up to it!)

Biggest disappointment: Speak to Me by Paula Cocozza

A 2023 book that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Prophet Song by Paul Lynch

The worst books I read this year: Monica by Daniel Clowes, They by Kay Dick, Swallowing Geography by Deborah Levy and Self-Portrait in Green by Marie Ndiaye (1-star ratings are extremely rare for me; these were this year’s four)

The downright strangest book I read this year: Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

The Booker Prize 2023 Ceremony

Yesterday evening Eleanor Franzen of Elle Thinks and I had the enormous pleasure of attending the Booker Prize awards ceremony at Old Billingsgate in London. I won tickets through “The Booker Prize Book Club” Facebook group, which launched just 10 or so weeks ago but has already garnered over 6000 members from around the world. They ran a competition for shortlist book reviews and probably did not attract nearly as many entries as they expected to. This probably worked to my advantage, but as it’s the only prize I can recall winning for my writing, I am going to take it as a compliment nonetheless! I submitted versions of my reviews of If I Survive You and Western Lane – the only shortlistees that I’ve read – and it was the latter that won us tickets.

We arrived at the venue 15 minutes before the doors opened, sheltering from the drizzle under an overhang and keeping a keen eye on arrivals (Paul Lynch and sodden Giller Prize winner Sarah Bernstein, her partner wearing both a kilt and their several-week-old baby). Elle has a gift for small talk and we had a nice little chat with Jonathan Escoffery and his 4th Estate publicist before they were whisked inside. His head was spinning from the events of the week, including being part of a Booker delegation that met Queen Camilla.

There was a glitzy atmosphere, with a photographer-surrounded red carpet and large banners for each shortlisted novel along the opposite wall, plus an exhibit of the hand-bound editions created for each book. We enjoyed some glasses of champagne and canapés (the haddock tart was the winner) and collared Eric Karl Anderson of Lonesome Reader. It was lovely to catch up with him and Eleanor and do plenty of literary celebrity spotting: Graeme Macrae Burnet, Eleanor Catton, judge Mary Jean Chan, Natalie Haynes, Alan Hollinghurst, Anna James, Jean McNeil, Johanna Thomas-Corr (literary editor of the Sunday Times) and Sarah Waters. Later we were also able to chat with Julianne Pachico, our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel winner from 2017. She has recently gotten married and released her third novel.

We were allocated to Table 11 in the front right corner. Also at our table were some Booker Prize editorial staff members, the other competition winner (for a video review) and her guest, an Instagram influencer, a Reading Agency employee, and several more people. The three-course dinner was of a very high standard for mass catering and the wine flowed generously. I thoroughly enjoyed my meal. Afterward we had a bit of time for taking red carpet photos and one of Eleanor with the banner for our predicted winner, Prophet Song.

Some of you may have watched the YouTube livestream, or listened to the Radio 4 live broadcast. Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s speech was a highlight. She spoke about the secret library at the Iranian prison where she was held for six years. Doctor Thorne by Anthony Trollope, War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (there was a long waiting list among the prisoners and wardens, she said), and especially The Return by Hisham Matar meant a lot to her. From earlier on in the evening, I also enjoyed judge Adjoa Andoh’s dramatic reading of an excerpt from Possession in honour of the late Booker winner A.S. Byatt, and Shehan Karunatilaka’s tongue-in-cheek reflections on winning the Booker – he warned the next winner that they won’t write a word for a whole year.

There was a real variety of opinion in the room as to who would win. Earlier in the evening we’d spoken to people who favoured Western Lane, This Other Eden and The Bee Sting. But both Elle and I were convinced that Prophet Song would take home the trophy, and so it did. Despite his genuine display of shock, Paul Lynch was well prepared with an excellent speech in which he cited the apocrypha and Albert Camus. In a rapid-fire interview with host Samira Ahmed, he added that he can still remember sitting down and weeping after finishing The Mayor of Casterbridge, age 15 or 16, and hopes that his work might elicit similar emotion. I’m not sure that I plan on reading it myself, but from what I’ve heard it’s a powerfully convincing dystopian novel that brings political and social collapse home in a realistic way.

All in all, a great experience for which I am very grateful! (Thanks to Eleanor for all the photos.)

Have you read Prophet Song? Did you expect it to win the Booker Prize?

#NovNov23 Week 4, “The Short and the Long of It”: W. Somerset Maugham & Jan Morris

Hard to believe, but it’s already the final full week of Novellas in November and we have had 109 posts so far! This week’s prompt is “The Short and the Long of It,” for which we encourage you to pair a novella with a nonfiction book or novel that deals with similar themes or topics. The book pairings week of Nonfiction November is always a favourite (my 2023 contribution is here), so think of this as an adjacent – and hopefully fun – project. I came up with two pairs: one fiction and one nonfiction. In the first case, the longer book led me to read a novella, and it was vice versa for the second.

W. Somerset Maugham

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng (2023)

&

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham (1897)

I wasn’t a huge fan of The Garden of Evening Mists, but as soon as I heard that Tan Twan Eng’s third novel was about W. Somerset Maugham, I was keen to read it. Maugham is a reliably readable author; his books are clearly classic literature but don’t pose the stylistic difficulties I now experience with Dickens, Trollope et al. And yet I know that Booker Prize followers who had neither heard of nor read Maugham have enjoyed this equally. I’m surprised it didn’t make it past the longlist stage, as I found it as revealing of a closeted gay writer’s life and times as The Master (shortlisted in 2004) but wider in scope and more rollicking because of its less familiar setting, true crime plot and female narration.

The main action is set in 1921, as “Willie” Somerset Maugham and his secretary, Gerald, widely known to be his lover, rest from their travels in China and the South Seas via a two-week stay with Robert and Lesley Hamlyn at Cassowary House in Penang, Malaysia. Robert and Willie are old friends, and all three men fought in the First World War. Willie’s marriage to Syrie Wellcome (her first husband was the pharmaceutical tycoon) is floundering and he faces financial ruin after a bad investment. He needs a good story that will sell and gets one when Lesley starts recounting to him the momentous events of 1910, including a crisis in her marriage, volunteering at the party office of Chinese pro-democracy revolutionary Dr Sun Yat Sen, and trying to save her friend Ethel Proudlock from a murder charge.

It’s clever how Tan weaves all of this into a Maugham-esque plot that alternates between omniscient third-person narration and Lesley’s own telling. The glimpses of expat life and Asia under colonial rule are intriguing, and the scene-setting and atmosphere are sumptuous – worthy of the Merchant Ivory treatment. I was left curious to read more by and about Maugham, such as Selina Hastings’ biography. (Public library)

But for now I picked up one of the leather-bound Maugham books I got for free a few years ago. Amusingly, the novella-length Liza of Lambeth is printed in the same volume with the travel book On a Chinese Screen, which Maugham had just released when he arrived in Penang.

{SPOILERS AHEAD}

This was Maugham’s debut novel and drew on his time as a medical intern in the slums of London. In tone and content it falls almost perfectly between Dickens and Hardy, because on the one hand Liza Kemp and her neighbours are cheerful paupers even though they work in factories, have too many children and live in cramped quarters; on the other hand, alcoholism and domestic violence are rife, and the wages of sexual sin are death. All seems light to start with: an all-village outing to picnic at Chingford; pub trips; and harmless wooing as Liza rebuffs sweet Tom in favour of a flirtation with married Jim Blakeston.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

Liza isn’t entirely the stereotypical whore with the heart of gold, but she is a good-time girl (“They were delighted to have Liza among them, for where she was there was no dullness”) and I wonder if she could even have been a starting point for Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion. Maugham’s rendering of the cockney accent is over-the-top –

“‘An’ when I come aht,’ she went on, ‘’oo should I see just passin’ the ’orspital but this ’ere cove, an’ ’e says to me, ‘Wot cheer,’ says ’e, ‘I’m goin’ ter Vaux’all, come an’ walk a bit of the wy with us.’ ‘Arright,’ says I, ‘I don’t mind if I do.’”

– but his characters are less caricatured than Dickens’s. And, imagine, even then there was congestion in London:

“They drove along eastwards, and as the hour grew later the streets became more filled and the traffic greater. At last they got on the road to Chingford, and caught up numbers of other vehicles going in the same direction—donkey-shays, pony-carts, tradesmen’s carts, dog-carts, drags, brakes, every conceivable kind of wheeled thing, all filled with people”

In short, this was a minor and derivative-feeling work that I wouldn’t recommend to those new to Maugham. He hadn’t found his true style and subject matter yet. Luckily, there’s plenty of other novels to try. (Free mall bookshop) [159 pages]

Jan Morris

Conundrum by Jan Morris (1974)

&

Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides, A Biography by Paul Clements (2022)

Back in 2021, I reread and reviewed Conundrum during Novellas in November. It’s a short memoir that documents her spiritual journey towards her true identity – she was a trans pioneer and influential on my own understanding of gender. In his doorstopper of a biography, Paul Clements is careful to use female pronouns throughout, even when this is a little confusing (with Morris a choirboy, a soldier, an Oxford student, a father, and a member of the Times expedition that first summited Everest). I’m just over a quarter of the way through the book now. Morris left the Times before the age of 30, already the author of several successful travel books on the USA and the Middle East. I’ll have to report back via Love Your Library on what I think of this overall. At this point I feel like it’s a pretty workaday biography, comprehensive and drawing heavily on Morris’s own writings. The focus is on the work and the travels, as well as how the two interacted and influenced her life.

#NovNov23 Buddy Reads Reviewed: Western Lane & A Room of One’s Own

This year we set two buddy reads for Novellas in November: one contemporary work of fiction and one classic work of short nonfiction. Do let us know if you’ve been reading them and what you think!

A version of the below review, submitted via their Facebook book club group, won me a pair of tickets to this year’s Booker Prize ceremony!

A version of the below review, submitted via their Facebook book club group, won me a pair of tickets to this year’s Booker Prize ceremony!

You may also wish to have a look at the excellent reading guide on the Booker website.

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo (2023)

In the same way that you don’t have to love baseball or video games to enjoy The Art of Fielding or Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, it’s easy to warm to Western Lane even if you’ve never played squash. Debut author Chetna Maroo assumes reader unfamiliarity with her first line: “I don’t know if you have ever stood in the middle of a squash court – on the T – and listened to what is going on next door.” As Gopi looks back to the year that she was eleven – the year after she lost her mother – what she remembers is the echo of a ball hitting a wall. That first year of mourning, which was filled with compulsive squash training, reverberates just as strongly in her memory.

To make it through, Pa tells his three daughters, “You have to address yourself to something.” That something will be their squash hobby, he decides, but ramped up to the level of an obsession. Having lost my own mother just over a year ago, I could recognize in these characters the strategies people adopt to deflect grief. Keep busy. Go numb. Ignore your feelings. Get angry for no particular reason. Even within this small family, there’s a range of responses. Pa lets his electrician business slip; fifteen-year-old Mona develops a mild shopping addiction; thirteen-year-old Khush believes she still sees their mother.

Preparing for an upcoming squash tournament gives Gopi a goal to work towards, and a crush on thirteen-year-old Ged brightens long practice days. Maroo emphasizes the solitude and concentration required, alternating with the fleeting elation of performance. Squash players hover near the central T, from which most shots can be reached. Maroo, too, sticks close to the heart. Like all the best novellas, hers maintains a laser focus on character and situation. A child point-of-view can sound precocious or condescending. That is by no means the case here. Gopi’s perspective is convincing for her age at the time, yet hindsight is the prism that reveals the spectrum of intense emotions she experienced: sadness, estrangement from her immediate family, and rejection on the one hand; first love and anticipation on the other.

This offbeat, delicate coming-of-age story eschews the literary fireworks of other Booker Prize nominees. In place of stylistic flair is the sense that each word and detail has been carefully placed. Less is more. Rather than the dark horse in the race, I’d call it the reader favourite: accessible but with hidden depths. There are cinematic scenes where little happens outwardly yet what is unspoken between the characters – the gazes and tension – is freighted with meaning. (I could see this becoming a successful indie film.)

she and my uncle stood outside under the balcony of my bedroom until much later, and I knelt above them with my blanket around me. The three of us looked out at the black shapes of the rose arbour, the trees, the railway track. Stars appeared and disappeared. My knees began to ache. Below me, Aunt Ranjan wanted badly to ask Uncle Pavan how things stood now and Uncle Pavan wanted to tell her, but she wasn’t sure how to ask and he wasn’t sure how to begin. Soon, I thought, it would be morning, and night, and morning again, and it wouldn’t matter, except to someone watching from so far off that they couldn’t know yet.

The novella is illuminating on what is expected of young Gujarati women in England; on sisterhood and a bereaved family’s dynamic; but especially on what it is like to feel sealed off from life by grief. “I think there’s a glass court inside me,” Gopi says, but over the course of one quietly momentous year, the walls start to crack. (Public library) [161 pages]

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf (1929)

Here’s the thing about Virginia Woolf. I know she’s one of the world greats. I fully acknowledge that her books are incredibly important in the literary canon. But I find her unreadable. The last time I had any success was when I was in college. Orlando and To the Lighthouse both blew me away half a lifetime ago, but I’ve not been able to reread them or force my way through anything else (and I have tried: Mrs Dalloway, The Voyage Out and The Waves). In the meantime, I’ve read several novels about Woolf and multiple Woolf-adjacent reads (ones by Vita Sackville-West, or referencing the Bloomsbury Group). So I thought a book-length essay based on lectures she gave at Cambridge’s women’s colleges in 1928 would be the perfect point of attack.

Hmm. Still unreadable. Oh well!

In the end I skimmed A Room of One’s Own for its main ideas – already familiar to me, as was some of the language – but its argumentation, reliant as much on her own made-up examples as on literary history, failed to move me. Woolf alternately imagines herself as Mary Carmichael, a lady novelist trawling an Oxbridge library and the British Museum for her forebears; and as a reader of Carmichael’s disappointingly pedestrian Life’s Adventure. If only Carmichael had had the benefit of time and money, Woolf muses, she might have been good. As it is, it would take her another century to develop her craft. She also posits a sister for Shakespeare and probes the social conditions that made her authorship impossible.

In the end I skimmed A Room of One’s Own for its main ideas – already familiar to me, as was some of the language – but its argumentation, reliant as much on her own made-up examples as on literary history, failed to move me. Woolf alternately imagines herself as Mary Carmichael, a lady novelist trawling an Oxbridge library and the British Museum for her forebears; and as a reader of Carmichael’s disappointingly pedestrian Life’s Adventure. If only Carmichael had had the benefit of time and money, Woolf muses, she might have been good. As it is, it would take her another century to develop her craft. She also posits a sister for Shakespeare and probes the social conditions that made her authorship impossible.

This is important to encounter as an early feminist document, but I would have been okay with reading just the excerpts I’d already come across.

Some favourite lines:

“I thought how unpleasant it is to be locked out; and I thought how it is worse perhaps to be locked in”

“A very queer, composite being thus emerges. Imaginatively she [the woman in literature] is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant. She pervades poetry from cover to cover; she is all but absent from history.”

“Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom. And women have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but from the beginning of time. Women have had less intellectual freedom than the sons of Athenian slaves. Women, then, have not had a dog’s chance of writing poetry. That is why I have laid so much stress on money and a room of one’s own.”

(Secondhand purchase many years ago) [114 pages]

Love Your Library (and Life Update), October 2023

My thanks, as always, to Elle for her participation in this monthly meme, and to Laura for mentioning whenever she sources a book from the library!

I’m posting a bit later than usual because it’s been a busy time, and quite an emotional rollercoaster too. First was the high of my joint 40th birthday party with my husband (whose birthday is in late November) on Saturday evening. It required close to wedding levels of event planning and was stressful, especially in the week ahead, with lots of dropouts due to illness and changed plans. Yesterday and today, I’ve been up to my knees in dirty dishes, leftovers, and soiled tablecloths and bedding to try to get washed and dry. But it was a fantastic party in the end, bringing together people from lots of different areas of our lives. I’m so grateful to everyone who came to celebrate with cake, a quiz, a ceilidh, a bring-and-share/potluck meal, and dancing to the hits of 1983.

The next day was a bit of a crash back to earth as I snuck away from the house guests to attend my church’s annual Memorial Service. With All Hallows’ Eve and then All Saints coming up, it’s a traditional time to think about the dead, but all the more so because today is the first anniversary of my mother’s death. It’s taken me the full year to understand and accept, with both mind and heart, that she’s gone. I’m not marking the day in any particular way apart from having a cup of strong Earl Grey tea in her honour. I feel close to her when I read her journals, look at photographs, or see all the many items she gave me that I still use. We recently moved her remains to a different cemetery and it’s strangely comforting to think that her plot could also accommodate at least a portion of my ashes one day.

Love Your Library

Last week I was trained in how to use the library content management system and received log-ins for limited access to return, issue and renew books and search for information on the internal catalogue. It has been interesting to see how things work from the other side, having been a customer of the library system for over a decade. At busy times I will be able to help out behind the counter, but because I have to call a senior for literally anything more complicated, I am not a replacement for an employee. It is a sad reality that some libraries have to rely on volunteers in this way; none of the smaller branches in West Berkshire would be able to stay open without volunteers working alongside staff.

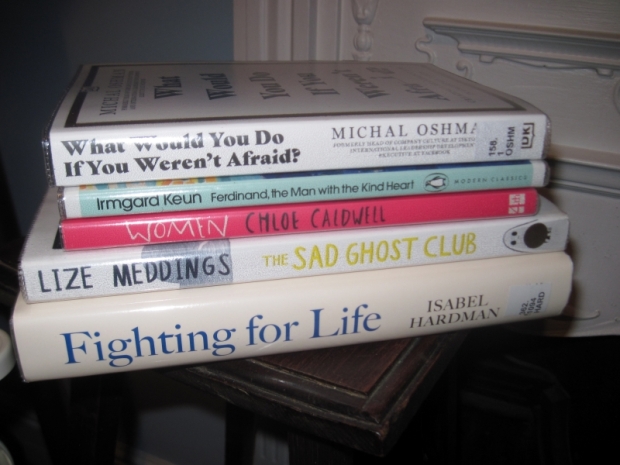

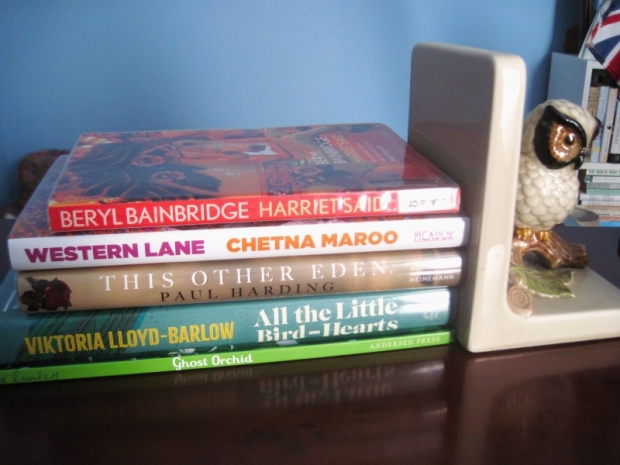

Novellas in November will be here before we know it. I have a huge pile of library novellas borrowed, in addition to all the ones I own.

Since last month:

READ

- The Whispers by Ashley Audrain

- I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Se-hee

- The Seaside by Madeleine Bunting

- Penance by Eliza Clark

- Emily Wilde’s Encyclopaedia of Faeries by Heather Fawcett

- By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah (for book club)

- Milk by Alice Kinsella

- The Sad Ghost Club by Lize Meddings

CURRENTLY READING

- Western Lane by Chetna Maroo

- The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward

CURRENTLY (NOT) READING

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Coslett

- Reproduction by Louisa Hall

- Weyward by Emilia Hart

- The Last Bookwanderer by Anna James

- Findings by Kathleen Jamie (a re-read)

- Before the Light Fades by Natasha Walter

I started all of the above weeks ago, but they have been languishing on various stacks and it will take a concerted effort to get back to and finish them.

RETURNED UNREAD

- The Seventh Son by Sebastian Faulks

- This Other Eden by Paul Harding

- All the Little Bird-Hearts by Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow

All were much-hyped or prize-listed novels that didn’t grab me within the first few pages, so I relinquished them to the next person in the reservation queue.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.