Classic and Doorstopper of the Month: East of Eden by John Steinbeck (1952)

Look no further for the Great American Novel. Spanning from the Civil War to World War I and crossing the country from New England to California, East of Eden is just as wide-ranging in its subject matter, with an overarching theme of good and evil as it plays out in families and in individual souls. This weighty material – openly addressed in theological and philosophical terms in the course of the novel – is couched in something of a family saga that follows several generations of the Trasks and the Hamiltons. (Some spoilers follow.)

Cyrus Trask, Civil War amputee and fraudulent hero, has two sons. He sends his beloved boy, Adam, into the army during the Indian Wars. Adam’s half-brother Charles stays home to tend the family’s Connecticut farm. There’s a bitter sibling rivalry between them; more than once it looks like Charles might beat Adam to death. When Cyrus, now high up in military administration in Washington, dies and leaves his sons $100,000, Charles is suspicious. He’s sure their father stole the money, but Adam won’t accept that. Adam takes his inheritance and buys a ranch outside Salinas, California, taking with him his new wife Cathy, who turned up battered on the brothers’ doorstep and won’t reveal anything about her shadowy background.

Cathy is that rare thing: a female villain, and one with virtually no redeeming features. No sooner has she given birth to Adam’s twin sons than she runs off, shooting him in the shoulder to get away. Unbeknownst to Adam, who still idealizes a wife he knows nothing about, she gets work in a Salinas brothel and before long takes over as the madam. As her sons Aron and Cal grow up, they hear rumors that make them doubt their mother is buried back East, as their father claims. Aron is drawn to the Church and falls for a girl named Abra, whom he puts on a pedestal just as he does his ‘dead’ mother. Cal, a wanderer and schemer, is determined not to follow his mother into vice even though that seems like his fate.

The John Steinbeck House (his childhood home) in Salinas, CA. By Ken Lund [CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons.

This was a buddy read with my mother. We were surprised by how much philosophy and theology Steinbeck includes. The parallels with the Cain and Abel story (brought to mind by both sets of C & A Trask brothers) are not buried in the text for an observant reader to find, but discussed explicitly. My favorite character and the novel’s most straightforward hero is Lee, Adam’s loyal Chinese cook, who practically raises Cal and Aron. When we first meet him he’s speaking pidgin, as is expected of him, but around friends he drops the act and can be his nurturing and deeply intellectual self. With some fellow Chinese scholars he’s picked apart Genesis 4 and zeroed in on one Hebrew word, timshel or “thou mayest.” To Lee this speaks of choice and possibility; life is not all pre-ordained. For the two central families it is a message of hope: one does not have to replicate family mistakes.

Steinbeck with his third wife, Elaine Scott, in 1950. The character of Cathy may be based on his second wife, Gwyn Conger, who cheated on him on multiple occasions and asked for a divorce. [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

At 600 small-type pages, this is a big book with many minor threads and secondary characters I haven’t even touched on. Steinbeck grapples with primal stories about human nature and examines how we try to earn love and break free from others’ expectations. His depiction of America’s contradictions still feels true, and he writes simply stunning sentences. “It is one of the best books I’ve ever read,” my mother told me. It’s a classic you really shouldn’t pass up.

Page count: 602

My rating:

A few favorite passages:

“It is the dull eventless times that have no duration whatever. A time splashed with interest, wounded with tragedy, crevassed with joy—that’s the time that seems long in the memory.”

“Adam Trask grew up in grayness, and the curtains of his life were like dusty cobwebs, and his days a slow file of half-sorrows and sick dissatisfactions, and then, through Cathy, the glory came to him.”

“We have only one story. All novels, all poetry, are built on the never-ending contest in ourselves of good and evil. And it occurs to me that evil must constantly respawn, while good, while virtue, is immortal. Vice has always a new fresh young face, while virtue is venerable as nothing else in the world is.”

During the month I spent reading this I could hardly get these two songs out of my head. Both seem to be at least loosely inspired by East of Eden. I’ve pulled out some key lines and linked to audio or video footage.

When the clouds roll in, we start playing for our sins

With a gun in my hand and my son at my shoulder

Believe I will run before that boy gets older […]

Ask the angels, “Am I heaven-bound?”

“By the Skin of My Teeth” by Duke Special

My luck ran out just east of Eden

Oh, I proved you right

I’m a danger […]

I’m tired, don’t let me be a failure

Hurled into Gettysburg: Poems by Theresa Wyatt

Today marks the start of the 155th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, which took place on July 1–3, 1863. Theresa Wyatt was so kind as to send her terrific book of commemorative poems all the way to England for me. She pays tribute to forgotten and fringe players of the Civil War, such as Elizabeth C. Thorn, who served as the gatekeeper of Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery from 1862 to 1865 while her husband was off fighting, and Jennie Wade, the only civilian killed by a war sniper. “Jennie & Jack” includes fragments of letters written by Jennie and her childhood friend and sweetheart Johnston Skelly, who died of an infection just nine days after her; neither was aware of the other’s demise. Another great story is that of poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier, whose colorblindness may have been a disadvantage growing up on a farm but was a metaphorical boon in the days of slavery.

Today marks the start of the 155th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, which took place on July 1–3, 1863. Theresa Wyatt was so kind as to send her terrific book of commemorative poems all the way to England for me. She pays tribute to forgotten and fringe players of the Civil War, such as Elizabeth C. Thorn, who served as the gatekeeper of Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery from 1862 to 1865 while her husband was off fighting, and Jennie Wade, the only civilian killed by a war sniper. “Jennie & Jack” includes fragments of letters written by Jennie and her childhood friend and sweetheart Johnston Skelly, who died of an infection just nine days after her; neither was aware of the other’s demise. Another great story is that of poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier, whose colorblindness may have been a disadvantage growing up on a farm but was a metaphorical boon in the days of slavery.

The poems are also peopled by immigrant settlers, Underground Railroad passengers (“divinity squeezing / into dark tight spaces”) on the run from slave hunters, and brothers fighting on opposite sides. On a recent visit to Gettysburg Wyatt imagines herself into the position of General Buford, “descending these stairs in flawless summer light, / uplifted by a cyclorama of clear view, fortified” – a clever reference to the famous Gettysburg Cyclorama.

In “Visiting Gettysburg” she captures the sense of overwhelmed helplessness one experiences in relation to great historical tragedies: “trying to take it all in as if I knew anything at all / about horses, cannons or bloodshed.” The imagery ranges from grisly through innocuous to lovely, so that “buckets full of gangrene – a country’s highest price” contrast with “drops of ruby blood / invisible to sight or touch / [that] have mingled into blooms” on a farm that once comprised part of the battlefield. Especially if you’ve visited Gettysburg or another military site recently, you’ll find these poems truly resonate. It’s hard not to devour them within one sitting.

Another favorite passage: “Some people like their heroes loud / and let them talk, but sometimes history / picks off the scabs of arrogance / when setting records straight.” (from “At the Jennie Wade Monument”)

Readalikes:

March by Geraldine Brooks

Into the Cyclorama by Annie Kim

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

Doorstopper of the Month: By Gaslight by Steven Price

My 2017 goal of reading one book of 500+ pages per month has been a mixed success. With the best doorstoppers the pages fly by and you enjoy every minute spent in a fictional world. From this past year Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle fits that bill, and a couple of novels I read years ago on holidays also come to mind: Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell and Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White. But then there are the books that feel like they’ll never end and you have to drag yourself through page by page.

Unfortunately, Steven Price’s second novel, By Gaslight, a Victorian cat-and-mouse mystery, tended more towards the latter group for me. Like Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, it has the kernel of a fascinating story but piles up the words unnecessarily. Between July and August I read the first 300 pages and then skimmed the rest (in total the paperback has 731 small-type pages). This is the story of William Pinkerton, a 39-year-old Civil War veteran and private investigator from Chicago who comes to London in 1885 to chase up a name from his father’s files: Edward Shade. His best lead comes to nothing when Charlotte Reckitt evades him and turns up as a set of dismembered remains in the Thames. Keeping in mind the rudimentary state of forensics, though, there’s some uncertainty about the corpse’s identity.

Unfortunately, Steven Price’s second novel, By Gaslight, a Victorian cat-and-mouse mystery, tended more towards the latter group for me. Like Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, it has the kernel of a fascinating story but piles up the words unnecessarily. Between July and August I read the first 300 pages and then skimmed the rest (in total the paperback has 731 small-type pages). This is the story of William Pinkerton, a 39-year-old Civil War veteran and private investigator from Chicago who comes to London in 1885 to chase up a name from his father’s files: Edward Shade. His best lead comes to nothing when Charlotte Reckitt evades him and turns up as a set of dismembered remains in the Thames. Keeping in mind the rudimentary state of forensics, though, there’s some uncertainty about the corpse’s identity.

The other central character in this drama is Adam Foole, a master thief. Half Indian and half English, he has violet eyes and travels in the company of Molly, a young pickpocket he passes off as his daughter, and Japheth Fludd, a vegetarian giant just out of prison. Foole was Charlotte’s lover ten years ago in South Africa, where they together pulled off a legendary diamond heist. Now he’s traveling back to England: she’s requested his help with a job as she knows she’s being tailed by a detective. The remaining cast is large and Dickensian: a medium and her lawyer brother, Charlotte’s imprisoned uncle, sewer dwellers, an opium dealer, and so on. Settings include a rare goods emporium, a Miss Havisham-type lonely manor house, the Record Office at Chancery Lane, and plenty of shabby garrets.

What I most enjoyed about the book was the restless, outlaw spirit of both main characters, but particularly Pinkerton. His troubled relationship with his father, in whose footsteps he’s following as a detective, is especially poignant: “William feared him and loved him and loathed him every day of his life yet too not a day passed that he did not want to be him.”

Price’s style is not what you’d generally expect of a Victorian pastiche. He uses no speech marks and his punctuation is non-standard, with lots of incomplete or run-in sentences like the one above. The critics’ blurbs liken By Gaslight to William Faulkner or Cormac McCarthy, apt comparisons that tell you just how unusual a hybrid it is.

I liked Price’s writing and starting around page 150 found the book truly gripping for a time, but extended flashbacks to Pinkerton and Foole’s earlier years really drag the story down, taking away from the suspense of the hunt. Meanwhile, the two major twists aren’t confirmed until over halfway through, but are hinted at so early that the watchful reader will know what’s going on long before the supposedly shrewd Pinkerton does. The salient facts about both characters’ past might have been conveyed in one short chapter each and the 1885 plot streamlined to make a taut novel of less than half the length.

There are many reasons to admire this Canadian novelist’s achievement, but whether it’s a reading experience you’d enjoy is something you’ll have to decide for yourself.

A favorite passage:

There is in every life a shadow of the possible, she said to him. The almost and the might have been. There are the histories that never were. We imagine we are keeping our accounts but what we are really saying is, I was here, I was real, this did happen once. It happened.

My rating:

By Gaslight was first published in the UK by Oneworld in September 2016. My thanks to Margot Weale for sending a free paperback for review.

Fun trivia: Steven Price is married to Esi Edugyan, author of the Booker Prize-shortlisted novel Half Blood Blues.

Nancy appeals to the Colberts’ adult daughter, Rachel Blake, to accompany her on her walks so that Martin will not “overtake” her in the woods. Although none of the white characters take the repeated threat of attempted rape seriously enough, Henry and Rachel do eventually help Nancy escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad. When Sapphira realizes her ‘property’ has been taken from her, she informs Rachel she is now persona non grata, but changes her mind when illness brings tragedy into Rachel’s household.

Nancy appeals to the Colberts’ adult daughter, Rachel Blake, to accompany her on her walks so that Martin will not “overtake” her in the woods. Although none of the white characters take the repeated threat of attempted rape seriously enough, Henry and Rachel do eventually help Nancy escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad. When Sapphira realizes her ‘property’ has been taken from her, she informs Rachel she is now persona non grata, but changes her mind when illness brings tragedy into Rachel’s household. Published when Thomas was in his mid-twenties, this is a series of 10 sketches, some of which are more explicitly autobiographical (as in first person, with a narrator named Dylan Thomas) than others. There is a rough chronological trajectory to the stories, with the main character a mischievous boy, then a grandstanding teenager, then a young journalist in his first job. The countryside and seaside towns of South Wales recur as settings, and – as will be no surprise to readers of Under Milk Wood – banter-filled dialogue is the priority. I most enjoyed the childhood japes in the first two pieces, “The Peaches” and “A Visit to Grandpa’s.” The rest failed to hold my attention, but I marked out two long passages that to me represent the voice and scene-setting that the Dylan Thomas Prize is looking for. The latter is the ending of the book and reminds me of the close of James Joyce’s “The Dead.” (University library)

Published when Thomas was in his mid-twenties, this is a series of 10 sketches, some of which are more explicitly autobiographical (as in first person, with a narrator named Dylan Thomas) than others. There is a rough chronological trajectory to the stories, with the main character a mischievous boy, then a grandstanding teenager, then a young journalist in his first job. The countryside and seaside towns of South Wales recur as settings, and – as will be no surprise to readers of Under Milk Wood – banter-filled dialogue is the priority. I most enjoyed the childhood japes in the first two pieces, “The Peaches” and “A Visit to Grandpa’s.” The rest failed to hold my attention, but I marked out two long passages that to me represent the voice and scene-setting that the Dylan Thomas Prize is looking for. The latter is the ending of the book and reminds me of the close of James Joyce’s “The Dead.” (University library) That’s not the only personal experience that went into his new book, Technologies of the Human Corpse, which I’m now keen to read. In 2018 his younger sister, Julie, died of brain cancer at age 43, so her illness and death became a late addition to the preface and also fed into a series of prose poems interspersed between the narrative chapters. She lived in Italy and her doctors failed to tell her that she was dying – that job fell to Troyer. (Unfortunately, this seems to be a persistent problem in Italy. In Dottoressa, her memoir of being an American doctor in Rome, which I read for a TLS review, Susan Levenstein writes of a paternalistic attitude among medical professionals: they treat their patients as children and might not even tell them about a cancer diagnosis; they just inform their family.)

That’s not the only personal experience that went into his new book, Technologies of the Human Corpse, which I’m now keen to read. In 2018 his younger sister, Julie, died of brain cancer at age 43, so her illness and death became a late addition to the preface and also fed into a series of prose poems interspersed between the narrative chapters. She lived in Italy and her doctors failed to tell her that she was dying – that job fell to Troyer. (Unfortunately, this seems to be a persistent problem in Italy. In Dottoressa, her memoir of being an American doctor in Rome, which I read for a TLS review, Susan Levenstein writes of a paternalistic attitude among medical professionals: they treat their patients as children and might not even tell them about a cancer diagnosis; they just inform their family.)

I’ve read an abnormally large number of books about death, especially in the five years since my brother-in-law died of brain cancer (one reason why Troyer’s talk was so meaningful for me). Most recently, I read Bodies in Motion and at Rest (2000) by Thomas Lynch, a set of essays by the Irish-American undertaker and poet from Michigan. I saw him speak at Greenbelt Festival in 2012 and have read four of his books since then. His unusual dual career lends lyrical beauty to his writing about death. However, this collection was not memorable for me in comparison to his 1997 book The Undertaking, and I’d already encountered a shortened version of “Wombs” in the Wellcome Collection anthology

I’ve read an abnormally large number of books about death, especially in the five years since my brother-in-law died of brain cancer (one reason why Troyer’s talk was so meaningful for me). Most recently, I read Bodies in Motion and at Rest (2000) by Thomas Lynch, a set of essays by the Irish-American undertaker and poet from Michigan. I saw him speak at Greenbelt Festival in 2012 and have read four of his books since then. His unusual dual career lends lyrical beauty to his writing about death. However, this collection was not memorable for me in comparison to his 1997 book The Undertaking, and I’d already encountered a shortened version of “Wombs” in the Wellcome Collection anthology

The Florist’s Daughter by Patricia Hampl: (As featured in my

The Florist’s Daughter by Patricia Hampl: (As featured in my

A Certain Loneliness: A Memoir by Sandra Gail Lambert: (A proof copy passed on by an online book reviewing friend.) A memoir in 29 essays about living with the effects of severe polio. Most of the pieces were previously published in literary magazines. While not all are specifically about the author’s disability, the challenges of life in a wheelchair seep in whether she’s writing about managing a feminist bookstore or going on camping and kayaking adventures in Florida’s swamps. I was reminded at times of Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson.

A Certain Loneliness: A Memoir by Sandra Gail Lambert: (A proof copy passed on by an online book reviewing friend.) A memoir in 29 essays about living with the effects of severe polio. Most of the pieces were previously published in literary magazines. While not all are specifically about the author’s disability, the challenges of life in a wheelchair seep in whether she’s writing about managing a feminist bookstore or going on camping and kayaking adventures in Florida’s swamps. I was reminded at times of Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson.  No Happy Endings: A Memoir by Nora McInerny: (Borrowed from my sister.) I didn’t appreciate this as much as the author’s first memoir,

No Happy Endings: A Memoir by Nora McInerny: (Borrowed from my sister.) I didn’t appreciate this as much as the author’s first memoir,  Native Guard by Natasha Trethewey: (Free from 2nd & Charles.) Trethewey writes beautifully disciplined verse about her mixed-race upbringing in Mississippi, her mother’s death and the South’s legacy of racial injustice. She occasionally rhymes, but more often employs forms that involve repeated lines or words. The title sequence concerns a black Civil War regiment in Louisiana. Two favorites from this Pulitzer-winning collection by a former U.S. poet laureate were “Letter” and “Miscegenation”; stand-out passages include “In my dream, / the ghost of history lies down beside me, // rolls over, pins me beneath a heavy arm” (from “Pilgrimage”) and “I return / to Mississippi, state that made a crime // of me — mulatto, half-breed” (from “South”).

Native Guard by Natasha Trethewey: (Free from 2nd & Charles.) Trethewey writes beautifully disciplined verse about her mixed-race upbringing in Mississippi, her mother’s death and the South’s legacy of racial injustice. She occasionally rhymes, but more often employs forms that involve repeated lines or words. The title sequence concerns a black Civil War regiment in Louisiana. Two favorites from this Pulitzer-winning collection by a former U.S. poet laureate were “Letter” and “Miscegenation”; stand-out passages include “In my dream, / the ghost of history lies down beside me, // rolls over, pins me beneath a heavy arm” (from “Pilgrimage”) and “I return / to Mississippi, state that made a crime // of me — mulatto, half-breed” (from “South”).  I also read the first half or more of: The Music Shop by Rachel Joyce, my June book club book; Hungry by Jeff Gordinier, a journalist’s travelogue of his foodie journeys with René Redzepi of Noma fame, coming out in July; and the brand-new novel In West Mills by De’Shawn Charles Winslow – these last two are for upcoming BookBrowse reviews.

I also read the first half or more of: The Music Shop by Rachel Joyce, my June book club book; Hungry by Jeff Gordinier, a journalist’s travelogue of his foodie journeys with René Redzepi of Noma fame, coming out in July; and the brand-new novel In West Mills by De’Shawn Charles Winslow – these last two are for upcoming BookBrowse reviews.

March by Geraldine Brooks (2005): The best Civil War novel I’ve read. The best slavery novel I’ve read. One of the best historical novels I’ve ever read, period. Brooks’s second novel uses Little Women as its jumping-off point but is very much its own story. The whole is a perfect mixture of what’s familiar from history and literature and what Brooks has imagined.

March by Geraldine Brooks (2005): The best Civil War novel I’ve read. The best slavery novel I’ve read. One of the best historical novels I’ve ever read, period. Brooks’s second novel uses Little Women as its jumping-off point but is very much its own story. The whole is a perfect mixture of what’s familiar from history and literature and what Brooks has imagined. Marlena by Julie Buntin (2017): The northern Michigan setting pairs perfectly with the novel’s tone of foreboding: you have a sense of these troubled teens being isolated in their clearing in the woods, and from one frigid winter through a steamy summer and into the chill of the impending autumn, they have to figure out what in the world they are going to do with their terrifying freedom. It’s basically a flawless debut, one I can’t recommend too highly.

Marlena by Julie Buntin (2017): The northern Michigan setting pairs perfectly with the novel’s tone of foreboding: you have a sense of these troubled teens being isolated in their clearing in the woods, and from one frigid winter through a steamy summer and into the chill of the impending autumn, they have to figure out what in the world they are going to do with their terrifying freedom. It’s basically a flawless debut, one I can’t recommend too highly. Reading in the Dark by Seamus Deane (1996): Ireland’s internecine violence is the sinister backdrop to this family’s everyday sorrows, including the death of a child and the mother’s shaky mental health. The book captures all the magic, uncertainty and heartache of being a child, in crisp scenes I saw playing out in my mind.

Reading in the Dark by Seamus Deane (1996): Ireland’s internecine violence is the sinister backdrop to this family’s everyday sorrows, including the death of a child and the mother’s shaky mental health. The book captures all the magic, uncertainty and heartache of being a child, in crisp scenes I saw playing out in my mind. The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt by Tracy Farr (2013): Lena Gaunt: early theremin player, grande dame of electronic music, and opium addict. I loved how Farr evokes the strangeness and energy of theremin music, and how sound waves find a metaphorical echo in the ocean’s waves – swimming is Lena’s other great passion.

The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt by Tracy Farr (2013): Lena Gaunt: early theremin player, grande dame of electronic music, and opium addict. I loved how Farr evokes the strangeness and energy of theremin music, and how sound waves find a metaphorical echo in the ocean’s waves – swimming is Lena’s other great passion. Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay (2007): A tight-knit cast gathers around the local radio station in Yellowknife, a small city in Canada’s Northwest Territories: Harry and Gwen, refugees from Ontario starting new lives; Dido, an alluring Dutch newsreader; Ralph, the freelance book reviewer; menacing Eddie; and pious Eleanor. This is a marvellous story of quiet striving and dislocation; I saw bits of myself in each of the characters, and I loved the extreme setting, both mosquito-ridden summer and bitter winter.

Late Nights on Air by Elizabeth Hay (2007): A tight-knit cast gathers around the local radio station in Yellowknife, a small city in Canada’s Northwest Territories: Harry and Gwen, refugees from Ontario starting new lives; Dido, an alluring Dutch newsreader; Ralph, the freelance book reviewer; menacing Eddie; and pious Eleanor. This is a marvellous story of quiet striving and dislocation; I saw bits of myself in each of the characters, and I loved the extreme setting, both mosquito-ridden summer and bitter winter. The Leavers by Lisa Ko (2017): An ambitious and satisfying novel set in New York and China, with major themes of illegal immigration, searching for a mother and a sense of belonging, and deciding what to take with you from your past. This was hand-picked by Barbara Kingsolver for the 2016 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction.

The Leavers by Lisa Ko (2017): An ambitious and satisfying novel set in New York and China, with major themes of illegal immigration, searching for a mother and a sense of belonging, and deciding what to take with you from your past. This was hand-picked by Barbara Kingsolver for the 2016 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction. The Invisible Bridge by Julie Orringer (2010): Hungarian Jew Andras Lévi travels from Budapest to Paris to study architecture, falls in love with an older woman who runs a ballet school, and – along with his parents, brothers, and friends – has to adjust to the increasingly strict constraints on Jews across Europe in 1937–45. It’s all too easy to burn out on World War II narratives these days, but this is among the very best I’ve read.

The Invisible Bridge by Julie Orringer (2010): Hungarian Jew Andras Lévi travels from Budapest to Paris to study architecture, falls in love with an older woman who runs a ballet school, and – along with his parents, brothers, and friends – has to adjust to the increasingly strict constraints on Jews across Europe in 1937–45. It’s all too easy to burn out on World War II narratives these days, but this is among the very best I’ve read. The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell (1996): For someone like me who struggles with sci-fi at the best of times, this is just right: the alien beings are just different enough from humans for Russell to make fascinating points about gender roles, commerce and art, but not so peculiar that you have trouble believing in their existence. All of the crew members are wonderful, distinctive characters, and the novel leaves you with so much to think about: unrequited love, destiny, faith, despair, and the meaning to be found in life.

The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell (1996): For someone like me who struggles with sci-fi at the best of times, this is just right: the alien beings are just different enough from humans for Russell to make fascinating points about gender roles, commerce and art, but not so peculiar that you have trouble believing in their existence. All of the crew members are wonderful, distinctive characters, and the novel leaves you with so much to think about: unrequited love, destiny, faith, despair, and the meaning to be found in life. Salt Creek by Lucy Treloar (2015): Hester Finch is looking back from the 1870s – when she is a widowed teacher settled in England – to the eight ill-fated years her family spent at Salt Creek, a small (fictional) outpost in South Australia, in the 1850s–60s. This is one of the very best works of historical fiction I’ve read; it’s hard to believe it’s Treloar’s debut novel.

Salt Creek by Lucy Treloar (2015): Hester Finch is looking back from the 1870s – when she is a widowed teacher settled in England – to the eight ill-fated years her family spent at Salt Creek, a small (fictional) outpost in South Australia, in the 1850s–60s. This is one of the very best works of historical fiction I’ve read; it’s hard to believe it’s Treloar’s debut novel. Christmas Days: 12 Stories and 12 Feasts for 12 Days by Jeanette Winterson (2016): I treated myself to this new paperback edition with part of my birthday book token and it was a perfect read for the week leading up to Christmas. The stories are often fable-like, some spooky and some funny. Most have fantastical elements and meaningful rhetorical questions. Winterson takes the theology of Christmas seriously. A gorgeous book I’ll return to year after year.

Christmas Days: 12 Stories and 12 Feasts for 12 Days by Jeanette Winterson (2016): I treated myself to this new paperback edition with part of my birthday book token and it was a perfect read for the week leading up to Christmas. The stories are often fable-like, some spooky and some funny. Most have fantastical elements and meaningful rhetorical questions. Winterson takes the theology of Christmas seriously. A gorgeous book I’ll return to year after year. Available Light by Marge Piercy (1988): The subjects are diverse: travels in Europe, menstruation, identifying as a Jew as well as a feminist, scattering her father’s ashes, the stresses of daily life, and being in love. Some of my favorites were about selectively adhering to the lessons her mother taught her, how difficult it is for a workaholic to be idle, and wrestling the deity for words.

Available Light by Marge Piercy (1988): The subjects are diverse: travels in Europe, menstruation, identifying as a Jew as well as a feminist, scattering her father’s ashes, the stresses of daily life, and being in love. Some of my favorites were about selectively adhering to the lessons her mother taught her, how difficult it is for a workaholic to be idle, and wrestling the deity for words. Deep Country: Five Years in the Welsh Hills by Neil Ansell (2011): One of the most memorable nature/travel books I’ve ever read; a modern-day Walden. Ansell’s memoir is packed with beautiful lines as well as philosophical reflections on the nature of the self and the difference between isolation and loneliness.

Deep Country: Five Years in the Welsh Hills by Neil Ansell (2011): One of the most memorable nature/travel books I’ve ever read; a modern-day Walden. Ansell’s memoir is packed with beautiful lines as well as philosophical reflections on the nature of the self and the difference between isolation and loneliness. Boy by Roald Dahl

Boy by Roald Dahl  This Cold Heaven: Seven Seasons in Greenland by Gretel Ehrlich

This Cold Heaven: Seven Seasons in Greenland by Gretel Ehrlich  Ali: A Life by Jonathan Eig (2017): It’s a riveting account of outliving segregation and developing a personal style and world-beating confidence; it’s a sobering tale of facing consequences and having your own body fail you. I’m the furthest thing from a sports fan you could imagine, but I approached this as a book about a cultural icon and read it with a spirit of curiosity about how Eig would shape this life story and separate the facts from the legend. I loved it.

Ali: A Life by Jonathan Eig (2017): It’s a riveting account of outliving segregation and developing a personal style and world-beating confidence; it’s a sobering tale of facing consequences and having your own body fail you. I’m the furthest thing from a sports fan you could imagine, but I approached this as a book about a cultural icon and read it with a spirit of curiosity about how Eig would shape this life story and separate the facts from the legend. I loved it. The Book of Forgotten Authors by Christopher Fowler (2017): A charming introduction to 99 more or less obscure writers. Each profile is a perfectly formed mini-biography with a survey of the author’s major work: in just two or three pages, Fowler is able to convey all a writer’s eccentricities and why their output is still worth remembering.

The Book of Forgotten Authors by Christopher Fowler (2017): A charming introduction to 99 more or less obscure writers. Each profile is a perfectly formed mini-biography with a survey of the author’s major work: in just two or three pages, Fowler is able to convey all a writer’s eccentricities and why their output is still worth remembering. To the Is-Land: An Autobiography by Janet Frame (1982): This is some of the best writing about childhood and memory that I’ve ever read, infused with music, magic and mystery. The prose alternates between dreamy and matter-of-fact as Frame describes growing up in New Zealand one of five children in the Depression and interwar years.

To the Is-Land: An Autobiography by Janet Frame (1982): This is some of the best writing about childhood and memory that I’ve ever read, infused with music, magic and mystery. The prose alternates between dreamy and matter-of-fact as Frame describes growing up in New Zealand one of five children in the Depression and interwar years. Leaving Before the Rains Come by Alexandra Fuller (2015): This poignant sequel to Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight is a portrait of Fuller’s two-decade marriage, from its hopeful beginnings to its acrimonious end. What I most appreciated about the book was Fuller’s sense of being displaced: she no longer feels African, but nor does she feel American.

Leaving Before the Rains Come by Alexandra Fuller (2015): This poignant sequel to Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight is a portrait of Fuller’s two-decade marriage, from its hopeful beginnings to its acrimonious end. What I most appreciated about the book was Fuller’s sense of being displaced: she no longer feels African, but nor does she feel American. West With the Night by Beryl Markham (1942): Markham writes so vividly about the many adventures of her life in Africa: hunting lions, training race horses, and becoming one of the continent’s first freelance pilots, delivering mail and locating elephant herds. Whether she’s reflecting on the many faces of Africa or the peculiar solitude of night flights, the prose is just stellar.

West With the Night by Beryl Markham (1942): Markham writes so vividly about the many adventures of her life in Africa: hunting lions, training race horses, and becoming one of the continent’s first freelance pilots, delivering mail and locating elephant herds. Whether she’s reflecting on the many faces of Africa or the peculiar solitude of night flights, the prose is just stellar. And When Did You Last See Your Father? by Blake Morrison (1993): An extraordinary memoir based around the author’s relationship with his father. Alternating chapters give glimpses into earlier family life and narrate Morrison’s father’s decline and death from cancer. This is simply marvelously written, not a bad line in the whole thing.

And When Did You Last See Your Father? by Blake Morrison (1993): An extraordinary memoir based around the author’s relationship with his father. Alternating chapters give glimpses into earlier family life and narrate Morrison’s father’s decline and death from cancer. This is simply marvelously written, not a bad line in the whole thing. The Seabird’s Cry: The Lives and Loves of Puffins, Gannets and Other Ocean Voyagers by Adam Nicolson (2017): This is an extraordinarily well-written and -researched book (a worthy Wainwright Prize winner) about the behavior, cultural importance, and current plight of the world’s seabirds. Each chapter takes up a different species and dives deep into everything from its anatomy to the legends surrounding it, simultaneously conveying the playful, intimate real lives of the birds and their complete otherness.

The Seabird’s Cry: The Lives and Loves of Puffins, Gannets and Other Ocean Voyagers by Adam Nicolson (2017): This is an extraordinarily well-written and -researched book (a worthy Wainwright Prize winner) about the behavior, cultural importance, and current plight of the world’s seabirds. Each chapter takes up a different species and dives deep into everything from its anatomy to the legends surrounding it, simultaneously conveying the playful, intimate real lives of the birds and their complete otherness. The Long Goodbye: A Memoir of Grief by Meghan O’Rourke (2011)

The Long Goodbye: A Memoir of Grief by Meghan O’Rourke (2011) Ghosts of the Tsunami: Death and Life in Japan’s Disaster Zone by Richard Lloyd Parry (2017): Eighteen and a half thousand people died in the earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan in March 2011. It’s not really possible to get your head around a tragedy on that scale so, wisely, Parry focuses on a smaller story within the story: 74 died at Okawa primary school because the administration didn’t have a sufficient disaster plan in place. This is a stunning portrait of a resilient people, but also a universal story of the human spirit facing the worst.

Ghosts of the Tsunami: Death and Life in Japan’s Disaster Zone by Richard Lloyd Parry (2017): Eighteen and a half thousand people died in the earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan in March 2011. It’s not really possible to get your head around a tragedy on that scale so, wisely, Parry focuses on a smaller story within the story: 74 died at Okawa primary school because the administration didn’t have a sufficient disaster plan in place. This is a stunning portrait of a resilient people, but also a universal story of the human spirit facing the worst. Lots of Candles, Plenty of Cake by Anna Quindlen (2012): A splendid memoir-in-essays that dwells on aging, parenting and female friendship. Some of its specific themes are marriage, solitude, the randomness of life, the process of growing into your own identity, and the special challenges her generation (roughly my mother’s) faced in seeking a work–life balance. Her words are witty and reassuring, and cut right to the heart of the matter in every case.

Lots of Candles, Plenty of Cake by Anna Quindlen (2012): A splendid memoir-in-essays that dwells on aging, parenting and female friendship. Some of its specific themes are marriage, solitude, the randomness of life, the process of growing into your own identity, and the special challenges her generation (roughly my mother’s) faced in seeking a work–life balance. Her words are witty and reassuring, and cut right to the heart of the matter in every case. The Happiness Project: Or, Why I Spent a Year Trying to Sing in the Morning, Clean My Closets, Fight Right, Read Aristotle, and Generally Have More Fun by Gretchen Rubin (2009): Probably the best self-help book I’ve read; dense (in the best possible way) with philosophy, experience and advice. What I appreciated most is that her approach is not about undertaking extreme actions to try to achieve happiness, but about finding contentment in the life you already have by adding or tweaking small habits – especially useful for pessimists like me.

The Happiness Project: Or, Why I Spent a Year Trying to Sing in the Morning, Clean My Closets, Fight Right, Read Aristotle, and Generally Have More Fun by Gretchen Rubin (2009): Probably the best self-help book I’ve read; dense (in the best possible way) with philosophy, experience and advice. What I appreciated most is that her approach is not about undertaking extreme actions to try to achieve happiness, but about finding contentment in the life you already have by adding or tweaking small habits – especially useful for pessimists like me. In the Days of Rain: A daughter. A father. A cult by Rebecca Stott (2017): This was a perfect book for my interests, and just the kind of thing I would love to write someday. It’s a bereavement memoir that opens with Stott’s father succumbing to pancreatic cancer and eliciting her promise to help finish his languishing memoir; it’s a family memoir that tracks generations through England, Scotland and Australia; and it’s a story of faith and doubt, of the absolute certainty experienced inside the Exclusive Brethren (a Christian sect that numbers 45,000 worldwide) and how that cracked until there was no choice but to leave.

In the Days of Rain: A daughter. A father. A cult by Rebecca Stott (2017): This was a perfect book for my interests, and just the kind of thing I would love to write someday. It’s a bereavement memoir that opens with Stott’s father succumbing to pancreatic cancer and eliciting her promise to help finish his languishing memoir; it’s a family memoir that tracks generations through England, Scotland and Australia; and it’s a story of faith and doubt, of the absolute certainty experienced inside the Exclusive Brethren (a Christian sect that numbers 45,000 worldwide) and how that cracked until there was no choice but to leave. Writers & Company by Eleanor Wachtel (1993): Erudite and fascinating author interviews from Wachtel’s weekly Canadian Broadcasting Corporation radio program. Whether I’d read anything by these authors (or even heard of them) or not, I found each Q&A chock-full of priceless nuggets of wisdom about creativity, mothers and daughters, drawing on autobiographical material, the writing process, and much more.

Writers & Company by Eleanor Wachtel (1993): Erudite and fascinating author interviews from Wachtel’s weekly Canadian Broadcasting Corporation radio program. Whether I’d read anything by these authors (or even heard of them) or not, I found each Q&A chock-full of priceless nuggets of wisdom about creativity, mothers and daughters, drawing on autobiographical material, the writing process, and much more.

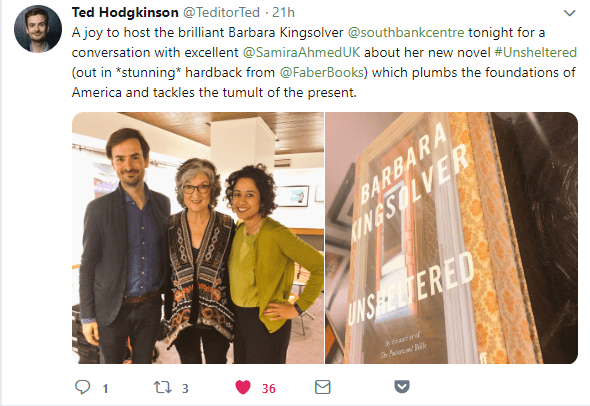

In person Kingsolver was a delight – warm and funny, with a generic American accent that doesn’t betray her Kentucky roots. In her beaded caftan and knee-high oxblood boots, she exuded girlish energy despite the shock of white in her hair. Although her fervor for the scientific method and a socially responsible government came through clearly, there was a lightness about her that tempered the weighty issues she covers in her novel.

In person Kingsolver was a delight – warm and funny, with a generic American accent that doesn’t betray her Kentucky roots. In her beaded caftan and knee-high oxblood boots, she exuded girlish energy despite the shock of white in her hair. Although her fervor for the scientific method and a socially responsible government came through clearly, there was a lightness about her that tempered the weighty issues she covers in her novel.

) and have also been moderating their online book club discussion of it. It’s been fascinating to see the spread of opinions, especially in the thread asking readers to describe the novel in three words. Descriptors have ranged from “preachy,” “political” and “repressive” to “prophetic,” “hopeful” and “truth.” My own three-word summary was “Bold, complex, polarizing.” I sensed that Kingsolver was going to divide readers – American ones, anyway; British readers should be a lot more positive because even centrist politics here start significantly further left, and there is for the most part very little resistance to concepts like socialism and climate change. I have a feeling the site’s users are predominantly middle-class, middle-aged white ladies (which, to be fair, was also true of the London audience), and we know that they’re a bastion of Trump support.

) and have also been moderating their online book club discussion of it. It’s been fascinating to see the spread of opinions, especially in the thread asking readers to describe the novel in three words. Descriptors have ranged from “preachy,” “political” and “repressive” to “prophetic,” “hopeful” and “truth.” My own three-word summary was “Bold, complex, polarizing.” I sensed that Kingsolver was going to divide readers – American ones, anyway; British readers should be a lot more positive because even centrist politics here start significantly further left, and there is for the most part very little resistance to concepts like socialism and climate change. I have a feeling the site’s users are predominantly middle-class, middle-aged white ladies (which, to be fair, was also true of the London audience), and we know that they’re a bastion of Trump support.