20 Books of Summer, #16–17, GREEN: Jon Dunn and W.H. Hudson

Today’s entries in my colour-themed summer reading are a travelogue tracking the world’s endangered hummingbirds and a bizarre classic novel that blends nature writing and fantasy. Though very different books, they have in common lush South American forest settings.

The Glitter in the Green: In Search of Hummingbirds by Jon Dunn (2021)

As a wildlife writer and photographer, Jon Dunn has come to focus on small and secretive but indelible wonders. His previous book, which I still need to catch up on, was all about orchids, and in this new one he travels the length of the Americas, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, to see as many hummingbirds as he can. He provides a thorough survey of the history, science and cultural relevance (from a mini handgun to an indie pop band) of this most jewel-like of bird families. The ruby-throated hummingbirds I grew up seeing in suburban Maryland are gorgeous enough, but from there the names and corresponding colourful markings just get more magnificent: Glittering-throated Emeralds, Tourmaline Sunangels, Violet-capped woodnymphs, and so on. I’ll have to get a look at the photos in a finished copy of the book!

Dunn is equally good at describing birds and their habitats and at constructing a charming travelogue out of his sometimes fraught journeys. He has only a narrow weather of fog-free weather to get from Chile to Isla Robinson Crusoe and the plane has to turn back once before it successfully lands; a planned excursion in Bolivia is a non-starter after political protestors block some main routes. There are moments when the thrill of the chase is rewarded – as when he sees 24 hummingbird species in a day in Costa Rica – and many instances of lavish hospitality from locals who serve as guides or open their gardens to birdwatchers.

Dunn is equally good at describing birds and their habitats and at constructing a charming travelogue out of his sometimes fraught journeys. He has only a narrow weather of fog-free weather to get from Chile to Isla Robinson Crusoe and the plane has to turn back once before it successfully lands; a planned excursion in Bolivia is a non-starter after political protestors block some main routes. There are moments when the thrill of the chase is rewarded – as when he sees 24 hummingbird species in a day in Costa Rica – and many instances of lavish hospitality from locals who serve as guides or open their gardens to birdwatchers.

Like so many creatures, hummingbirds are in dire straits due to human activity: deforestation, invasive species, pesticide use and climate change are reducing the areas where they can live to pockets here and there; some species number in the hundreds and are considered critically endangered. Dunn juxtaposes the exploitative practices of (white, male) 19th- and 20th-century bird artists, collectors and hunters with indigenous birdwatching and environmental initiatives that are rising up to combat ecological damage in Latin America. Although society has moved past the use of hummingbird feathers in crafts and fashion, he learns that the troubling practice of dead hummingbirds being sold as love charms (chuparosas) persists in Mexico.

Whether you’re familiar with hummingbirds or not, if you have even a passing interest in nature and travel writing, I recommend The Glitter in the Green for how it invites readers into a personal passion, recreates an adventurous odyssey, and reinforces our collective responsibility for threatened wildlife. (Proof copy passed on by Paul of Halfman, Halfbook)

A lovely folk tale I’ll quote in full:

A hummingbird as a symbol of hope, strength and endurance is a recurrent one in South American folklore. An Ecuadorian folk tale tells of a forest on fire – a hummingbird picks up single droplets of water in its beak and lets them fall on the fire. The other animals in the forest laugh, and ask the hummingbird what difference this can possibly make. They say, ‘Don’t bother, it is too much, you are too little, your wings will burn, your beak is too tiny, it’s only a drop, you can’t put out this fire. What do you think you are doing?’ To which the hummingbird is said to reply, ‘I’m just doing what I can.’

Links between the books: Hudson is quoted in Dunn’s introduction. In Chapter 7 of the below, Hudson describes a hummingbird as “a living prismatic gem that changes its colour with every change of position … it catches the sunshine on its burnished neck and gorget plumes—green and gold and flame-coloured, the beams changing to visible flakes as they fall”

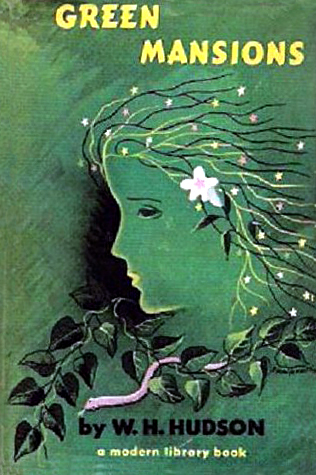

Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest by W.H. Hudson (1904)

Like Heart of Darkness, this is a long recounted tale about a journey among ‘savages’. After a prologue, the narrator soon cedes storytelling duties to Mr. Abel, whom he met in Georgetown, Guyana in 1887. Searching for gold and fighting off illness, the 23-year-old Abel took up the habit of wandering the Venezuelan forest. The indigenous people were superstitious and refused to hunt in that forest. Abel began to hear strange noises – magical bird calls or laughter – that, siren-like, drew him deeper in. His native friend warned him it was the daughter of an evil spirit.

Like Heart of Darkness, this is a long recounted tale about a journey among ‘savages’. After a prologue, the narrator soon cedes storytelling duties to Mr. Abel, whom he met in Georgetown, Guyana in 1887. Searching for gold and fighting off illness, the 23-year-old Abel took up the habit of wandering the Venezuelan forest. The indigenous people were superstitious and refused to hunt in that forest. Abel began to hear strange noises – magical bird calls or laughter – that, siren-like, drew him deeper in. His native friend warned him it was the daughter of an evil spirit.

One day, after being bitten by a snake, Abel woke up in the dwelling of an old man and his 17-year-old granddaughter, Rima – the very wood sprite he’d sensed all these times in the forest; she saved his life. Recovering in their home and helping Rima investigate her origins, he romanticizes this tree spirit in a way that struck me as smarmy. It’s possible this could be appreciated as a fable of connection with nature, but I found it vague and old-fashioned. (Not to mention Abel’s condescending attitude to the indigenous people and to women.) I ended up skimming the last three-quarters.

My husband has read nonfiction by Hudson; I think I was under the impression that this was a memoir, in fact. Perhaps I’d enjoy Hudson’s writing in another genre. But I was surprised to read high praise from John Galsworthy in the foreword (“For of all living authors—now that Tolstoi has gone—I could least dispense with W. H. Hudson”) and to note how many of my Goodreads friends have read this; I don’t see it as a classic that stands the test of time.

My 1944 hardback once belonged to one Mary Marcilliat of Louisville, Kentucky, and has strange abstract illustrations by E. McKnight Kauffer. (Free from the Book Thing of Baltimore)

Coming up next: One black and one gold on Wednesday; a Green author and a rainbow bonus (probably on the very last day).

Would you be interested in reading one of these?

Classic of the Month & 20 Books of Summer #5: A Pair of Blue Eyes by Thomas Hardy (1873)

While going through my boxes stored in my sister’s basement, I came across an antiquarian copy of this lesser-known Hardy novel. I used to place a lot more value on books’ age and rarity, whereas now I tend to just acquire readable paperback copies. I also used to get on much better with Victorian novels – I completed an MA in Victorian Literature, after all – but these days I generally find them tedious. Two years ago, I DNFed Hardy’s The Well-Beloved, and I ended up mostly skimming A Pair of Blue Eyes after the first 100 pages. In any case, it fit into my 20 Books of Summer colour theme. It’s sad for me that I’ve lost my love for my academic speciality, but life is long and I may well go back to Victorian literature someday.

I found similarities to Far from the Madding Crowd, my favourite Hardy novel, as well as to Hardy’s own life. As in FFTMC, the focus is on a vain young woman with three suitors. Elfride Swancourt is best known for her eyes, rapturously described as “blue as autumn distance—blue as the blue we see between the retreating mouldings of hills and woody slopes on a sunny September morning. A misty and shady blue, that had no beginning or surface, and was looked into rather than at.” Her vicar father, suffering from gout and sounding much older than his actual age (40 was a different prospect in that time!), warns her that architects will soon be arriving from London to plan restoration work on the church tower.

The young architectural assistant who arrives at the Swancourts’ coastal parish in “Lower Wessex” (North Devon?) is Stephen Smith, a clear Hardy stand-in, desperate to hide his humble background as he seeks to establish himself in his profession. Stephen emulates his friend Henry Knight, a dilettante essayist and book reviewer. Book learning has given Stephen passable knowledge of everything from Latin to chess, but he doesn’t know how to do practical things like ride a horse. Elfride and Stephen, predictably, fall in love, and she is determined to go ahead with an engagement even when she learns that his parents are a mason and a milkmaid, but her father refuses to grant permission. It’s intriguing that this poor clergyman fancies himself of the class of the Luxellians, local nobility, than of the Smiths.

{SPOILERS FOLLOW}

Elfride’s previous love died, and his pauper mother, Mrs Jethway, blames her still for toying with her boy’s affections. When Stephen takes a position in India and Mr Swancourt remarries and moves the family to London, Elfride’s eye wanders. Time for love interest #3. The family runs into Knight, who is a distant cousin of Mrs Swancourt. There’s another, juicier, connection: Elfride is a would-be author (she writes her father’s sermons for him, putting passages in brackets with the instruction “Leave this out if the farmers are falling asleep”) and publishes a medieval romance under a male pseudonym. A negative write-up of her book needles her. “What a plague that reviewer is to me!” And who is it but Knight?

They begin a romance despite this inauspicious coincidence and his flirty/haughty refusal to admire her fine eyes – “I prefer hazel,” he says. Some of the novel’s most memorable scenes, famous even beyond its immediate context, come from their courtship. Knight saves her from falling off the church tower, while she tears her dress into linen strips and ties them into a rope to rescue him from a sea cliff (scandalous!). Somewhere I’d read an in-depth account of this scene: as Knight dangles from the rock face, he spots a trilobite, which, in its very ancientness, mocks the precariousness of his brief human life. Lovingly created and personally watched over by a supreme being? Pshaw. Hardy’s was a godless vision, and I’ve always been interested in that Victorian transition from devoutness to atheism.

The novel’s span is too long, requiring a lot of jumps in time. I did appreciate that Mrs Jethway becomes the instrument of downfall, writing a warning letter to Knight about Elfride’s mistreatment of her son and another former fiancé. Knight breaks things off and it’s not until 15 months later, after he and Stephen bump into each other in London and Knight realizes that Stephen was her other suitor, that they travel back to Wessex to duke it out over the girl. When they arrive, though, it’s too late: Elfride had married but then fallen ill and died; her funeral is to take place the very next day. As the book closes at the vault, it’s her widower, Lord Luxellian, who has the right to mourn and not either of her previous loves.

{END OF SPOILERS}

As always with Hardy, I enjoyed the interplay of coincidence and fate. There were a few elements of this novel that I particularly liked: the coastal setting, the characters’ lines of work (including a potential profession for Elfride, though Knight told her in future she should stick to domestic scenes in her writing!) and the role played by a book review, but overall, this was not a story that is likely to stick with me. I did wonder to what extent it inspired Lars Mytting’s The Bell in the Lake, about a country girl who falls in love with the man who comes to oversee construction at the local church.

Source: Secondhand purchase, most likely from Wonder Book and Video in the early 2000s

My rating:

Novellas in November: 10 Favorite Classic Novellas

For this final week of Novellas in November, we’re focusing on classic literature. The more obscure the better, as far as I’m concerned. Maybe a few of the favorites I feature below will be new to you? (The two not pictured were read from the library.)

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin [150 pages]: David, a penniless American, came to Paris to find himself. His second year there he meets Giovanni, an Italian barman. They fall in love and move in together. There’s a problem, though: David has a fiancée. We know from the first pages that David has fled to the south of France and that Giovanni faces the guillotine in the morning, but throughout Baldwin maintains the tension as we wait to hear why he has been sentenced to death. Deeply sad, but also powerful and brave.

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin [150 pages]: David, a penniless American, came to Paris to find himself. His second year there he meets Giovanni, an Italian barman. They fall in love and move in together. There’s a problem, though: David has a fiancée. We know from the first pages that David has fled to the south of France and that Giovanni faces the guillotine in the morning, but throughout Baldwin maintains the tension as we wait to hear why he has been sentenced to death. Deeply sad, but also powerful and brave.

The Darling Buds of May by H.E. Bates [137 pages]: “Perfick” reading for an afternoon sitting or two; The Novel Cure even prescribes it as a tonic for cynicism. Just like tax inspector Cedric Charlton, you’ll find yourself drawn into the orbit of junk dealer Pop Larkin, Ma, and their six children at their country home in Kent – indomitably cheery hedonists, the lot of them. Ma and Pop are more calculating than they let on, but you can’t help but love them. Plus Bates writes so evocatively about the British countryside in late spring.

The Darling Buds of May by H.E. Bates [137 pages]: “Perfick” reading for an afternoon sitting or two; The Novel Cure even prescribes it as a tonic for cynicism. Just like tax inspector Cedric Charlton, you’ll find yourself drawn into the orbit of junk dealer Pop Larkin, Ma, and their six children at their country home in Kent – indomitably cheery hedonists, the lot of them. Ma and Pop are more calculating than they let on, but you can’t help but love them. Plus Bates writes so evocatively about the British countryside in late spring.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Capote [91 pages]: Whether you’ve seen the Audrey Hepburn film or not, this is delightful. Holly Golightly has remade herself as a New York City good-time girl, but her upstairs neighbor discovers her humble origins. This was from my pre-reviewing days, so I have no more detail to add. But whenever I think of its manic cocktail party scenes, I think of a holiday do from my final year of college: packed like sardines, everyone talking over each other, and my professor couldn’t stop shaking my hand.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Capote [91 pages]: Whether you’ve seen the Audrey Hepburn film or not, this is delightful. Holly Golightly has remade herself as a New York City good-time girl, but her upstairs neighbor discovers her humble origins. This was from my pre-reviewing days, so I have no more detail to add. But whenever I think of its manic cocktail party scenes, I think of a holiday do from my final year of college: packed like sardines, everyone talking over each other, and my professor couldn’t stop shaking my hand.

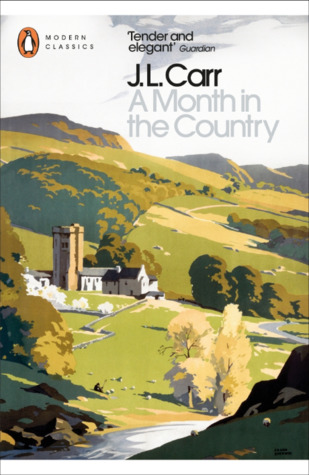

A Month in the Country by J.L. Carr [108 pages]: Summer 1920: Tom Birkin, a WWI veteran, arrives in North Yorkshire to uncover a local church’s medieval wall painting of the Judgment Day. With nothing awaiting him back in London, he gives himself over to the rhythms of working, eating and sleeping. Also embarked on a quest into the past is Charles Moon, searching for the grave of their patroness’ 14th-century ancestor in the churchyard. Moon, too, has a war history he’d rather forget. A Hardyesque, tragicomic romance.

A Month in the Country by J.L. Carr [108 pages]: Summer 1920: Tom Birkin, a WWI veteran, arrives in North Yorkshire to uncover a local church’s medieval wall painting of the Judgment Day. With nothing awaiting him back in London, he gives himself over to the rhythms of working, eating and sleeping. Also embarked on a quest into the past is Charles Moon, searching for the grave of their patroness’ 14th-century ancestor in the churchyard. Moon, too, has a war history he’d rather forget. A Hardyesque, tragicomic romance.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer [144 pages]: Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping, and she starts therapy. Meanwhile, her filmmaker husband is having a glass tower built as a countryside getaway, allowing her to contemplate an escape from motherhood. A razor-sharp period piece composed largely of dialogue, it gives a sense of a woman overwhelmed by responsibility.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer [144 pages]: Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping, and she starts therapy. Meanwhile, her filmmaker husband is having a glass tower built as a countryside getaway, allowing her to contemplate an escape from motherhood. A razor-sharp period piece composed largely of dialogue, it gives a sense of a woman overwhelmed by responsibility.

Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov [177 pages]: A comic novel about a Russian professor on an American college campus. In this episodic narrative spanning 1950–4, Timofey Pnin is a figure of fun but also of pathos: from having all his teeth pulled out and entertaining the son his ex-wife had by another man to failing to find and keep a home of his own, he deserves the phrase Nabokov originally thought to use as a title, “My Poor Pnin”. There are shades of Lucky Jim here – I laughed out loud at some of Pnin’s verbal gaffes and slapstick falls.

Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov [177 pages]: A comic novel about a Russian professor on an American college campus. In this episodic narrative spanning 1950–4, Timofey Pnin is a figure of fun but also of pathos: from having all his teeth pulled out and entertaining the son his ex-wife had by another man to failing to find and keep a home of his own, he deserves the phrase Nabokov originally thought to use as a title, “My Poor Pnin”. There are shades of Lucky Jim here – I laughed out loud at some of Pnin’s verbal gaffes and slapstick falls.

No Signposts in the Sea by Vita Sackville-West [156 pages]: Sackville-West’s last novel, published a year before her death, was inspired by world cruises she and her husband, Harold Nicolson, took in later life. Fifty-year-old Edmund Carr, a journalist with a few months to live, has embarked on a cruise ship voyage to be close to the woman he loves, 40-year-old war widow Laura Drysdale. He dares to hope she might return his feelings … but doesn’t tell her of his imminent demise. The novel is presented as Edmund’s diary, found after his death.

No Signposts in the Sea by Vita Sackville-West [156 pages]: Sackville-West’s last novel, published a year before her death, was inspired by world cruises she and her husband, Harold Nicolson, took in later life. Fifty-year-old Edmund Carr, a journalist with a few months to live, has embarked on a cruise ship voyage to be close to the woman he loves, 40-year-old war widow Laura Drysdale. He dares to hope she might return his feelings … but doesn’t tell her of his imminent demise. The novel is presented as Edmund’s diary, found after his death.

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger [192 pages]: Believe it or not, I didn’t read this until December 2018! From the start I found Holden Caulfield’s voice funny and surprising, so drenched in period American slang you can never forget when and where it’s set. He’s a typical lazy teenager, flunking four subjects when he’s kicked out of Pencey Prep. The first part is a languorous farewell tour to classmates and teachers before he takes the train back to NYC. Once there, he lives it up in a hotel for a few days. A shocker of an ending is to come.

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger [192 pages]: Believe it or not, I didn’t read this until December 2018! From the start I found Holden Caulfield’s voice funny and surprising, so drenched in period American slang you can never forget when and where it’s set. He’s a typical lazy teenager, flunking four subjects when he’s kicked out of Pencey Prep. The first part is a languorous farewell tour to classmates and teachers before he takes the train back to NYC. Once there, he lives it up in a hotel for a few days. A shocker of an ending is to come.

Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West [110 pages]: Like The Great Gatsby, this is a very American tragedy and state-of-the-nation novel. “Miss Lonelyhearts” is a male advice columnist for the New York Post-Dispatch. His letters come from a pitiable cross section of humanity: the abused, the downtrodden and the unloved. Not surprisingly, these second-hand woes start to get him down, and he turns to drink and womanizing for escape. West’s picture of how beleaguered compassion can turn to indifference feels utterly contemporary.

Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West [110 pages]: Like The Great Gatsby, this is a very American tragedy and state-of-the-nation novel. “Miss Lonelyhearts” is a male advice columnist for the New York Post-Dispatch. His letters come from a pitiable cross section of humanity: the abused, the downtrodden and the unloved. Not surprisingly, these second-hand woes start to get him down, and he turns to drink and womanizing for escape. West’s picture of how beleaguered compassion can turn to indifference feels utterly contemporary.

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton [181 pages]: Unlike Wharton’s NYC society novels, this has a rural setting, but the plot is not dissimilar to that of The Age of Innocence, with extra tragic sauce. The title character makes the mistake of falling in love with his wife’s cousin, and the would-be lovers are punished one New England winter. A quarter of a century later, the narrator learns what happened to this sad old man. It’s probably been 15 years since I’ve read this, and I like the catharsis of a good old-fashioned tragedy. Maybe I’ll reread it soon.

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton [181 pages]: Unlike Wharton’s NYC society novels, this has a rural setting, but the plot is not dissimilar to that of The Age of Innocence, with extra tragic sauce. The title character makes the mistake of falling in love with his wife’s cousin, and the would-be lovers are punished one New England winter. A quarter of a century later, the narrator learns what happened to this sad old man. It’s probably been 15 years since I’ve read this, and I like the catharsis of a good old-fashioned tragedy. Maybe I’ll reread it soon.

Not enough women on my list! I should redress that by reading some more Jean Rhys…

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll keep adding your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

Any suitably short classics on your shelves?

Summery Classics by J. L. Carr and L. P. Hartley

“Do you remember what that summer was like? – how much more beautiful than any since?”

These two slightly under-the-radar classics made for perfect heatwave reading over the past couple of weeks: very English and very much of the historical periods that they evoke, they are nostalgic works remembering one summer when everything changed – or could have.

A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr (1980)

Summer 1920, North Yorkshire. Tom Birkin, a First World War veteran whose wife has left him, arrives in Oxgodby to uncover the local church’s wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long since whitewashed over. With nothing waiting for him back in London and no plans beyond this commission, he gives himself over to the daily rhythms of working, eating and sleeping – “There was so much time that marvelous summer.” This simple life is punctuated by occasional incidents like a Sunday school hayride and picnic, and filling in as a lay preacher at a nearby chapel. Also embarked on a quest into the past is Charles Moon, who is searching for the grave of their patroness’ ancestor in the churchyard. Moon, too, has a war history he’d rather forget.

Summer 1920, North Yorkshire. Tom Birkin, a First World War veteran whose wife has left him, arrives in Oxgodby to uncover the local church’s wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long since whitewashed over. With nothing waiting for him back in London and no plans beyond this commission, he gives himself over to the daily rhythms of working, eating and sleeping – “There was so much time that marvelous summer.” This simple life is punctuated by occasional incidents like a Sunday school hayride and picnic, and filling in as a lay preacher at a nearby chapel. Also embarked on a quest into the past is Charles Moon, who is searching for the grave of their patroness’ ancestor in the churchyard. Moon, too, has a war history he’d rather forget.

Though it barely exceeds 100 pages, this novella is full of surprises – about Moon, about the presumed identity and fate of the centuries-dead figures he and Birkin come to be obsessed with, and about the emotional connection that builds between Birkin and Reverend Keach’s wife, Alice. “It is now or never; we must snatch at happiness as it flies,” Birkin declares, but did he take his own advice? There is something achingly gorgeous about this not-quite-love story, as evanescent as ideal summer days. Carr writes in a foreword that he intended to write “a rural idyll along the lines of Thomas Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree.” He indeed created something Hardyesque with this tragicomic rustic romance; I was also reminded of another very English classic I reviewed earlier in the year: Cider with Rosie by Laurie Lee.

Source: Free bookshop

My rating:

A contemporary readalike: The Offing by Benjamin Myers

The Go-Between by L. P. Hartley (1953)

Summer 1900, Norfolk. Twelve-year-old Leo Colston is invited to spend the several July weeks leading up to his birthday at his school friend Marcus Maudsley’s home, Brandham Hall. Although the fatherless boy is keenly aware of the class difference between their families, in a year of learning to evade bullies he’s developed some confidence in his skills and pluck, fancying himself an amateur magician and gifted singer. Being useful makes him feel less like a charity case, so he eagerly agrees to act as “postman” for Marcus’s older sister, Marian, who exchanges frequent letters with their tenant farmer, Ted Burgess. Marian, engaged to Hugh, a viscount and injured Boer War veteran, insists the correspondence is purely business-related, but Leo suspects he’s abetting trysts the family would disapprove of.

Leo is right on the cusp of adolescence, a moment of transition that mirrors the crossing into a new century. As he glories in the summer’s mounting heat, “a liberating power with its own laws,” and mentally goads the weather into hitting ever greater extremes, he pushes against the limits of his innocence, begging Ted to tell him about “spooning” (that is, the facts of life). The heat becomes a character in its own right, gloweringly presiding over the emotional tension caused by secrets, spells and betrayals. And yet this is also a very funny novel: I loved Leo’s Franglais conversations with Marcus, and the confusion over mispronouncing “Hugh” as “you.” In places the tone even reminded me of Cold Comfort Farm.

Leo is right on the cusp of adolescence, a moment of transition that mirrors the crossing into a new century. As he glories in the summer’s mounting heat, “a liberating power with its own laws,” and mentally goads the weather into hitting ever greater extremes, he pushes against the limits of his innocence, begging Ted to tell him about “spooning” (that is, the facts of life). The heat becomes a character in its own right, gloweringly presiding over the emotional tension caused by secrets, spells and betrayals. And yet this is also a very funny novel: I loved Leo’s Franglais conversations with Marcus, and the confusion over mispronouncing “Hugh” as “you.” In places the tone even reminded me of Cold Comfort Farm.

Like A Month in the Country, this autobiographical story is an old man’s reminiscences, going back half a century in memory – but here Leo gets the chance to go back in person as well, seeing what has become of Brandham Hall and meeting one of the major players from that summer drama that branded him for life. I thought this masterfully done in every way: the class divide, the picture of childhood tipping over into the teenage years, the oppressive atmosphere, the comical touches. You know from the famous first line onwards (“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there”) that this will juxtapose past and present – which, of course, has now become past and further past – in a powerful way, similar to Moon Tiger, my favorite fiction read of last year. I’ll be exploring more of Hartley’s work.

(Note: Although I am a firm advocate of DNFing if a book is not working for you, I would also like to put in a good word for trying a book again another time. Ironically, this had been a DNF for me last summer: I found the prologue, with all its talk of the zodiac, utterly dull. I had the same problem with Cold Comfort Farm, literally trying about three times to get through the prologue and failing. So, for both, I eventually let myself skip the prologue, read the whole novel, and then go back to the prologue. Worked a treat.)

Source: Ex-library copy bought from Lambeth Library when I worked in London

My rating:

A contemporary readalike: Atonement by Ian McEwan

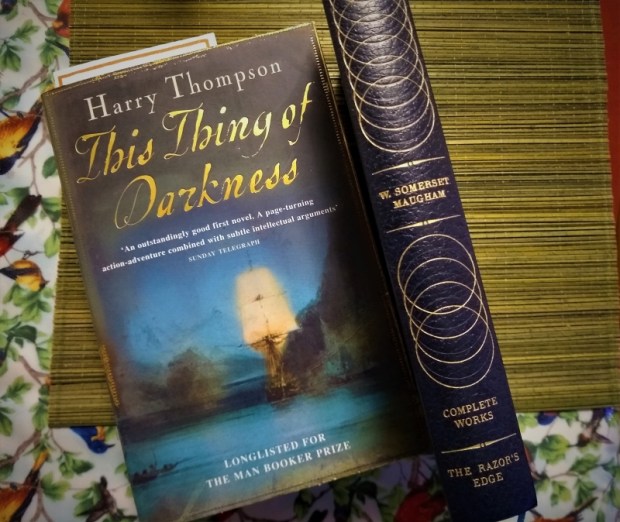

Classic of the Month: Cakes and Ale by W. Somerset Maugham (1930)

(20 Books of Summer, #12) This is the third Maugham novel I’ve reviewed here (after Of Human Bondage and The Moon and Sixpence) and my fourth overall. I’d recommend his work to fans of Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, or to anyone looking to expand their knowledge of the classics: his books are short (with the exception of Bondage) and accessible, and the frequent theme of struggling one’s way to love and creative success in defiance of poverty and a cruel fate resonates.

(20 Books of Summer, #12) This is the third Maugham novel I’ve reviewed here (after Of Human Bondage and The Moon and Sixpence) and my fourth overall. I’d recommend his work to fans of Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, or to anyone looking to expand their knowledge of the classics: his books are short (with the exception of Bondage) and accessible, and the frequent theme of struggling one’s way to love and creative success in defiance of poverty and a cruel fate resonates.

Cakes and Ale is narrated by an older writer named William Ashenden, a Maugham stand-in who previously appeared in the 1928 linked story collection Ashenden, widely recognized as the first English spy narrative. He’s contacted by a popular author of his acquaintance, Alroy Kear (“I could think of no one among my contemporaries who had achieved so considerable a position on so little talent”) with a request: Roy is writing the authorized biography of the late writer Edward Driffield, at his second wife’s behest. Remembering that Ashenden knew Driffield as a boy, Roy hopes to mine his memory for some good anecdotes. The book contains his resulting recollections – though Ashenden is unlikely to share them all with Roy.

Ashenden shares a background with Philip Carey from Of Human Bondage: both were raised in a vicar uncle’s household in Blackstable, Kent. Young Willie would go for bike rides with friendly neighbors Driffield and his wife Rosie, until his aunt and uncle forbade him.

{SPOILERS FOLLOW}

The Driffields, you see, were considered low-class and vulgar, an opinion that was seemingly confirmed first when they ran away from their debts to London, and then when Rosie left Edward for a Kent coal merchant. Rosie comes to represent a familiar type: the whore with the heart of gold. As Ashenden knows from personal experience, she enjoyed sex and slept with men out of kindness or pity. Only decades later did he learn that Edward knew Rosie was stepping out on him, and that the couple had lost a six-year-child to meningitis. This is not, I think, meant to excuse Rosie’s promiscuity, but it does give her an extra dimension, and perhaps explains why Driffield’s first marriage failed. Unfortunately, Rosie’s sexuality is racialized, with Driffield’s second wife saying, “I’ve always thought she looked rather like a white nigger” and an illustration giving her stereotypically wide nostrils and thick lips.)

{END OF SPOILERS}

I felt Driffield must be inspired by Thomas Hardy, and I’m not alone: in a preface, Maugham reports that many assumed he had Hardy in mind, but denies basing his portrait on any author in particular. Yet the similarities are undeniable: the flighty first wife; the late remarriage to his secretary; childlessness; humble origins and the fight to be taken seriously in the literary world. Maugham does, however, mention loving Tess of the d’Urbervilles and its milkmaid heroine, so Rosie is his homage (in the preface Maugham explains that, while the book’s plot occurred to him for a short story, he didn’t want to ‘waste’ Rosie on something so brief).

Dickens is an influence, too; I enjoyed references to his work, as well as to (on consecutive pages!) the New Woman and Mrs. Humphry Ward, both of whom were part of my MA thesis. The Victorian shadow is long here. But the focus on Rosie means Driffield himself is never more than a cipher. Ashenden admits this: “I am conscious that in what I have written of him I have not presented a living man, standing on his feet, rounded, with comprehensible motives and logical activities; I have not tried to: I am glad to leave that to the abler pen of Alroy Kear.” But The Moon and Sixpence, which employs the same setup of an author reminiscing about a great man he once knew, makes its subject a three-dimensional character, and is better for it.

Dickens is an influence, too; I enjoyed references to his work, as well as to (on consecutive pages!) the New Woman and Mrs. Humphry Ward, both of whom were part of my MA thesis. The Victorian shadow is long here. But the focus on Rosie means Driffield himself is never more than a cipher. Ashenden admits this: “I am conscious that in what I have written of him I have not presented a living man, standing on his feet, rounded, with comprehensible motives and logical activities; I have not tried to: I am glad to leave that to the abler pen of Alroy Kear.” But The Moon and Sixpence, which employs the same setup of an author reminiscing about a great man he once knew, makes its subject a three-dimensional character, and is better for it.

Note: Maugham’s titles are often unusual and allusive. “Cakes and ale,” as part of a Twelfth Night quotation, represent the luxurious lifestyle in opposition to the moral one. The book’s subtitle is “or The Skeleton in the Cupboard.”

Source: Free bookshop

My rating:

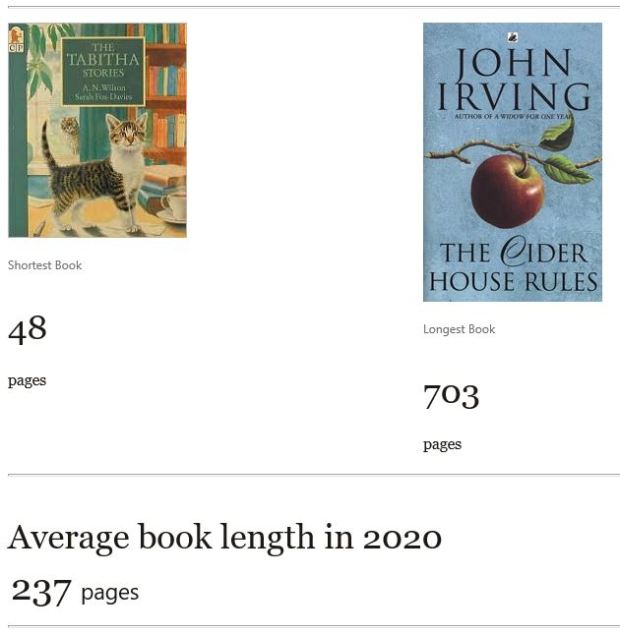

Reading Statistics for the First Half of 2020, Including Where My Books Came From

Almost halfway through the year: how am I doing on the reading goals I set for myself? Pretty well!

- It might not look like it from the statistics below, but I have drastically cut down on the number of review copies I’m requesting or accepting from publishers. (This time last year they made up 43% of my reading.)

- I’ve reread nine books so far, which is more than I can remember doing in any other year – and I intend to continue prioritizing rereads in the remaining months.

- Thanks to COVID-19, over the past few months I have been reading a lot less from the libraries I use and, consequently, more from my own shelves. This might continue into next month but thereafter, when libraries reopen, my borrowing will increase.

- I’ve also bought many more new books than is usual for me, to directly support authors and independent bookshops.

- I’m not managing one doorstopper per month (I’ve only done May so far, though I have a few lined up for June‒August), but I am averaging at least one classic per month (I only missed January, but made up for it with multiple in two other months).

- On literature in translation, I’m doing better: it’s made up 9.7% of my reading, versus 8.1% in 2019.

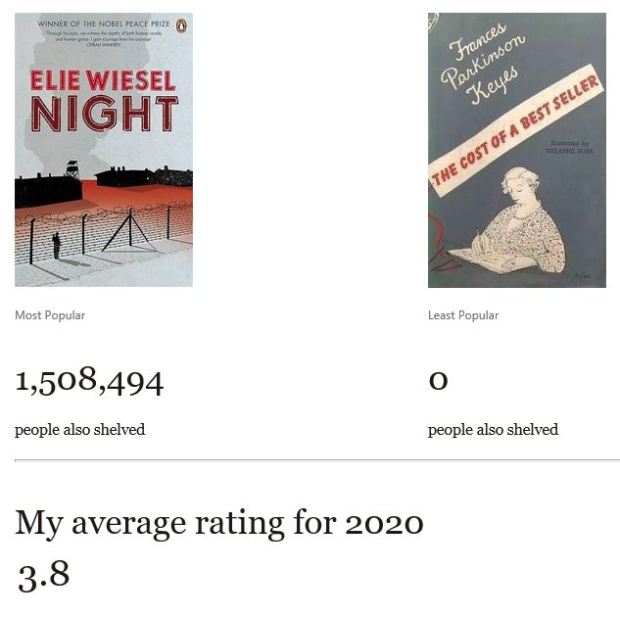

The breakdown:

Fiction: 57.6%

Nonfiction: 36.3%

Poetry: 6.1%

(This time last year I’d read exactly equal numbers of fiction and nonfiction books. Fiction seems to be winning this year. Poetry is down massively: last June it was at 15.4%.)

Male author: 34.7%

Female author: 63.5%

Anthologies with pieces by authors of multiple genders: 1.8%

(No non-binary authors so far this year. Even more female-dominated than last year.)

E-books: 12.7%

Print books: 87.3%

(E-books have crept up a bit since last year due to some publishers only offering PDF review copies during the pandemic, but I have still been picking up many more print books.)

I always find it interesting to look back at where my books come from. Here are the statistics for the year so far, in percentages (not including the books I’m currently reading, DNFs or books I only skimmed):

- Free print or e-copy from the publisher: 25.5%

- Public library: 21.2%

- Free, e.g. from Book Thing of Baltimore, local swap shop or free mall bookshop: 16.4%

- Secondhand purchase: 10.3%

- Downloaded from NetGalley or Edelweiss: 8.5%

- New purchase: 7.3%

- Gifts: 5.4%

- University library: 5.4%

How are you doing on any reading goals you set for yourself?

Where do you get most of your books from?

#1920Club Classics of the Month: Agatha Christie and F. Scott Fitzgerald

I’m sneaking in a couple of quick reviews on the final day to join in with Simon and Karen’s latest reading week, The 1920 Club. Speaking of books that were published a century ago, I happened to review Chéri by Colette as one of my monthly classics last year, and I’m currently reading The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton in advance of our May book club meeting.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles by Agatha Christie

I don’t think I’ve read an Agatha Christie mystery since I was about … 13? (It was And Then There Were None.) But over the years I’ve watched countless Poirot and Miss Marple cases on TV with my mother. This was Poirot’s first outing, and it’s narrated by Hastings, the slightly dim Watson to the Belgian detective’s Sherlock Holmes.

I don’t think I’ve read an Agatha Christie mystery since I was about … 13? (It was And Then There Were None.) But over the years I’ve watched countless Poirot and Miss Marple cases on TV with my mother. This was Poirot’s first outing, and it’s narrated by Hastings, the slightly dim Watson to the Belgian detective’s Sherlock Holmes.

One July, invalided home from the war at age 30, Hastings goes to visit old family friends at Styles, their Essex manor house: brothers John and Lawrence Cavendish and their elderly stepmother, who has recently (and somewhat shockingly) remarried. When old Mrs. Cavendish is found dead of strychnine poisoning, Poirot is brought in to sort through the potential suspects. Coffee and cocoa cups, a fragment of a charred will, a fake beard, a candle wax stain and a bolted door will be among his major clues.

Like Hastings, we as readers are quick to point to the obvious: hey, that foreigner who happens to be an expert on poisons, it’s him, right?! But as Poirot carefully explains, again and again, “If the fact will not fit the theory, let the theory go. … Real evidence is usually vague and unsatisfactory. It has to be examined, sifted. But here the whole thing is cut and dried.”

I rarely pick up a mystery novel, though when I can get stuck in I do tend to enjoy them. This was a super-quick read and I found myself turning to it more often than to other books on my stack that felt weightier in subject matter. In the end I find crime novels inconsequential, so can’t imagine needing to try another Poirot or Marple for another 20 years or so. But if you’re struggling to read in a time of anxiety, you could certainly do worse than a Christie novel.

My rating:

This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Fitzgerald has long been one of my literary blind spots. The Great Gatsby is a masterpiece, sure: I studied it in school and have read it another couple of times since, as well as lots of background nonfiction and some contemporary novels that riff on the story line. But everything else of his that I’ve tried (Tender Is the Night was the other one) has felt aimless and more stylish than substantive.

Fitzgerald has long been one of my literary blind spots. The Great Gatsby is a masterpiece, sure: I studied it in school and have read it another couple of times since, as well as lots of background nonfiction and some contemporary novels that riff on the story line. But everything else of his that I’ve tried (Tender Is the Night was the other one) has felt aimless and more stylish than substantive.

Amory Blaine is a wealthy Midwesterner who goes from boarding school to Princeton and has literary ambitions and various love affairs. He’s convinced he’s a “boy marked for glory.” But Monsignor Darcy, his guru, encourages the young man to focus on developing his character more than his dashing personality.

Hugely popular at its first release, this debut novel won Fitzgerald his literary reputation – as well as Zelda Sayre’s hand in marriage. What with the slang (“Oh my Lord, I’m going to cast a kitten”), it felt very much like a period piece to me, most impressive for its experimentation with structure: parts are written like a film script or Q&A, and there are also some poems and lists. This novelty may well be a result of the author cobbling together drafts and unpublished odds and ends, but still struck me as daring.

In a strange way, though, the novel is deliberately ahistorical in that it glosses over world events with a flippancy that I find typical of Fitzgerald. Even though Amory is called up to serve, his general reaction to the First World War is dispatched in a paragraph; Prohibition doesn’t get much more of a look-in.

I understand that the book is fairly autobiographical and in its original form was written in the first person, which I might have preferred if it led to greater sincerity. I could admire some of the witty banter and the general coming-of-age arc, but mostly felt indifferent to this one.

My rating:

This was meant to be a buddy read with

This was meant to be a buddy read with

I’d never read any P.G. Wodehouse before, but of course I was familiar with his two most famous creations, empty-headed aristocrat Bertie Wooster and his omniscient manservant, Jeeves. Many people are turning to cheerful, witty reads during lockdown, so this seemed like a perfect time to give one of the books a try. The bio in my secondhand paperback calls this the first set of Jeeves and Wooster tales, while Goodreads lists it as the third book in a 14-strong series. I didn’t realize when I bought this or picked it up to read that it was a collection of 10 short stories, but that makes sense – these are such silly, inconsequential plots that they couldn’t possibly be sustained for more than about 20 pages each.

I’d never read any P.G. Wodehouse before, but of course I was familiar with his two most famous creations, empty-headed aristocrat Bertie Wooster and his omniscient manservant, Jeeves. Many people are turning to cheerful, witty reads during lockdown, so this seemed like a perfect time to give one of the books a try. The bio in my secondhand paperback calls this the first set of Jeeves and Wooster tales, while Goodreads lists it as the third book in a 14-strong series. I didn’t realize when I bought this or picked it up to read that it was a collection of 10 short stories, but that makes sense – these are such silly, inconsequential plots that they couldn’t possibly be sustained for more than about 20 pages each.