Still More Books about Cats

The past two years I’ve had biannual specials on cat books. You might think I would have run out of options by now, but not so! Granted, my choices this time are rather light fare: several children’s picture books, two slight gift books, and a few breezy memoirs. But it’s nice to have a fluffy post every now and again, and today’s is in honor of getting past a week of the year I always dread: June 15th is the U.S. tax deadline for citizens living abroad, so I’ve been drowning in forms and numbers. To celebrate getting both my IRS and HMRC tax returns sent off by today, here’s some feline-themed reads to enjoy over a G&T or other summery tipple of your choice.

Alfie likes cat books, too. The stacks are good for scratching one’s cheek against.

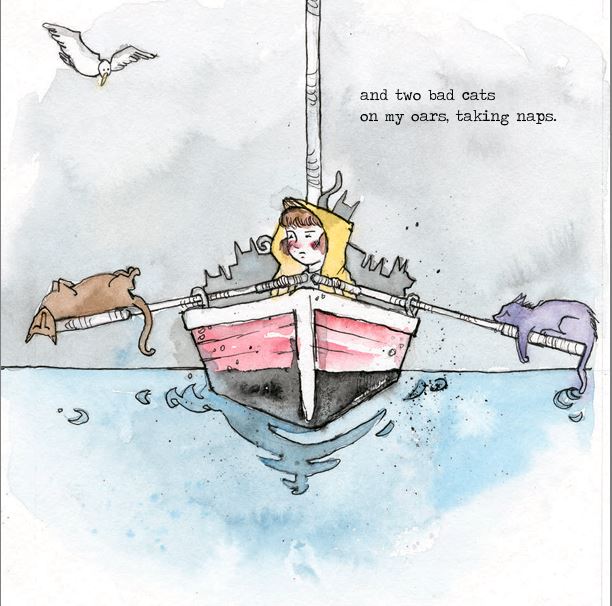

Seven Bad Cats by Monique Bonneau (2018): “Today I put on my boots and my coat, and seven bad cats jumped into my boat.” This is a terrific little rhyming book that counts up to seven and then back down to one with the help of some stowaway cats and their antics. (They come in colors that cats don’t normally come in, but that’s okay with me.) To start with they are incorrigibly lazy and mischievous, but when disaster is at hand they band together to help the little girl get back to shore safely. If only cats were so helpful in real life!

Seven Bad Cats by Monique Bonneau (2018): “Today I put on my boots and my coat, and seven bad cats jumped into my boat.” This is a terrific little rhyming book that counts up to seven and then back down to one with the help of some stowaway cats and their antics. (They come in colors that cats don’t normally come in, but that’s okay with me.) To start with they are incorrigibly lazy and mischievous, but when disaster is at hand they band together to help the little girl get back to shore safely. If only cats were so helpful in real life!

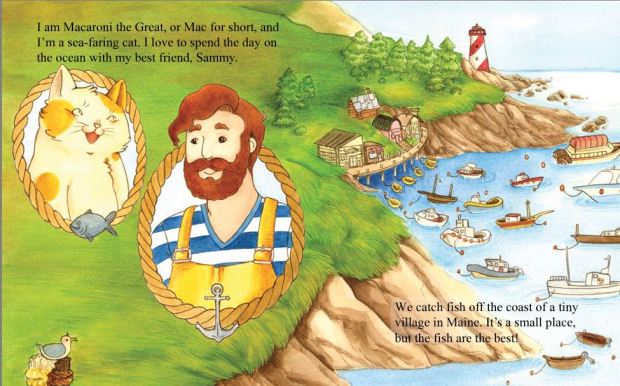

Macaroni the Great and the Sea Beast by Whitney Childers (2018): Macaroni the cat has an idyllic life by the coast of Maine with his hipster fisherman friend, Sammy. Sometimes he helps steer the fishing boat; sometimes he naps on the deck. But when a fearsome sea beast rears its head from the net one day, Mac is ready to fight back and save the day. From the colorfully nautical endpapers through to the peaceful last page, this is a great picture book for cat lovers to share with the little ones in their lives.

Macaroni the Great and the Sea Beast by Whitney Childers (2018): Macaroni the cat has an idyllic life by the coast of Maine with his hipster fisherman friend, Sammy. Sometimes he helps steer the fishing boat; sometimes he naps on the deck. But when a fearsome sea beast rears its head from the net one day, Mac is ready to fight back and save the day. From the colorfully nautical endpapers through to the peaceful last page, this is a great picture book for cat lovers to share with the little ones in their lives.

You don’t so often hear blokes talking about their cats, do you? That crazy cat lady stereotype dominates. But Tom Cox has written several memoirs about his life with cats.

In Under the Paw: Confessions of a Cat Man (2008), Cox, who had previously published volumes of his journalism about music and sports, came out as a cat lover. By the end of the book he has SIX CATS, so this was not some passing fad but a deep and possibly worrying obsession. In essays and short list-based asides he traces his history with cats, reveals the wildly different personalities of his current pets, and wittily comments on cat behavior. I especially liked these entries from his “Cat Dictionary”: “ES Pee: The telepathic process that leads a cat to only get properly settled on its owner’s stomach in the moments when that owner is most desperate for the toilet” & “Muzzlewug: The state of bliss created by the perfect friction of an owner’s fingers on a fully extended chin.”

In Under the Paw: Confessions of a Cat Man (2008), Cox, who had previously published volumes of his journalism about music and sports, came out as a cat lover. By the end of the book he has SIX CATS, so this was not some passing fad but a deep and possibly worrying obsession. In essays and short list-based asides he traces his history with cats, reveals the wildly different personalities of his current pets, and wittily comments on cat behavior. I especially liked these entries from his “Cat Dictionary”: “ES Pee: The telepathic process that leads a cat to only get properly settled on its owner’s stomach in the moments when that owner is most desperate for the toilet” & “Muzzlewug: The state of bliss created by the perfect friction of an owner’s fingers on a fully extended chin.”

The Good, the Bad and the Furry (2013) is another fairly entertaining book. Cat owners will recognize the ways in which a pet’s requirements impinge on their lives (but we wouldn’t have it any other way). Cox starts and ends the book with four cats, but – alas – goes down to three for a while in the middle, with visitors upping it to 3.5 sometimes. The Bear, Ralph and Shipley are the stalwarts, with The Bear described as “the only cat I’d ever seen who appeared to be almost permanently on the verge of tears.” He’s melancholy and philosophical, whereas Ralph (who says his own name when he meows) is vain and sullen. “The Ten Catmandments” was my favorite part: “Thou shalt not drink the water put out for thee by thy humans” and “Thou shalt ignore any toy thy human has bought for thee, especially the really expensive ones.” Includes lots of photographs of cats and kittens!

The Good, the Bad and the Furry (2013) is another fairly entertaining book. Cat owners will recognize the ways in which a pet’s requirements impinge on their lives (but we wouldn’t have it any other way). Cox starts and ends the book with four cats, but – alas – goes down to three for a while in the middle, with visitors upping it to 3.5 sometimes. The Bear, Ralph and Shipley are the stalwarts, with The Bear described as “the only cat I’d ever seen who appeared to be almost permanently on the verge of tears.” He’s melancholy and philosophical, whereas Ralph (who says his own name when he meows) is vain and sullen. “The Ten Catmandments” was my favorite part: “Thou shalt not drink the water put out for thee by thy humans” and “Thou shalt ignore any toy thy human has bought for thee, especially the really expensive ones.” Includes lots of photographs of cats and kittens!

How It Works: The Cat (2016) is a Ladybird pastiche by Jason Hazeley and Joel Morris that we purchased as a bargain book from Aldi; it was published in the USA as The Fireside Book of the Cat. Tongue-in-cheek descriptions sit opposite 1950s-style drawings. Cat owners will certainly get a chuckle from lines like “Dogs have evolved to serve many sorts of human needs. And humans have evolved to serve many sorts of cat food.” (However, “It is a good idea to buy a lot of your cat’s favourite food. That way, you will have something to throw away when she changes her mind.”) Makes a good coffee table book for guests to smile at.

How It Works: The Cat (2016) is a Ladybird pastiche by Jason Hazeley and Joel Morris that we purchased as a bargain book from Aldi; it was published in the USA as The Fireside Book of the Cat. Tongue-in-cheek descriptions sit opposite 1950s-style drawings. Cat owners will certainly get a chuckle from lines like “Dogs have evolved to serve many sorts of human needs. And humans have evolved to serve many sorts of cat food.” (However, “It is a good idea to buy a lot of your cat’s favourite food. That way, you will have something to throw away when she changes her mind.”) Makes a good coffee table book for guests to smile at.

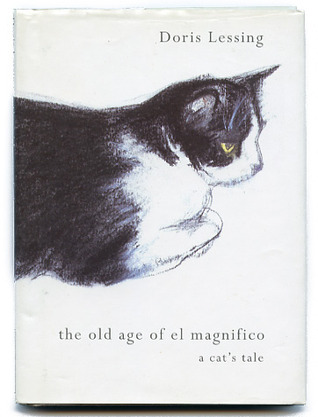

The Old Age of El Magnifico by Doris Lessing (2000): Pure cat lover’s delight. I wasn’t a big fan of Lessing’s Particularly Cats, which is surprisingly unsentimental and even brutal in places. This redresses the balance. It’s the bittersweet story of Butch, her enormous black and white cat, who was known by many additional nicknames including El Magnifico. At the age of 14 he was found to have a cancerous growth in his shoulder, and one entire front leg had to be removed. His habits, and even to an extent his personality, changed after the amputation, and Lessing regretted that she couldn’t let him know it was done for his good. She reflects on her duty towards the cats in her care, and on how pets encourage us to slow our pace and direct our attention fully to the present moment. Work? Chores? Worries? What could really be more important than sitting still and stroking a cat?

The Old Age of El Magnifico by Doris Lessing (2000): Pure cat lover’s delight. I wasn’t a big fan of Lessing’s Particularly Cats, which is surprisingly unsentimental and even brutal in places. This redresses the balance. It’s the bittersweet story of Butch, her enormous black and white cat, who was known by many additional nicknames including El Magnifico. At the age of 14 he was found to have a cancerous growth in his shoulder, and one entire front leg had to be removed. His habits, and even to an extent his personality, changed after the amputation, and Lessing regretted that she couldn’t let him know it was done for his good. She reflects on her duty towards the cats in her care, and on how pets encourage us to slow our pace and direct our attention fully to the present moment. Work? Chores? Worries? What could really be more important than sitting still and stroking a cat?

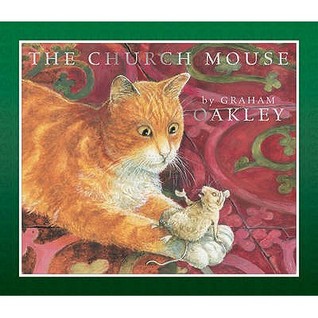

The Church Mouse by Graham Oakley: It is not good for a mouse to be alone. Arthur is lonely as the only mouse resident in the village church, but he has an idea: he proposes to the parson that if he will give all the local mice refuge in the church, they’ll undertake minor chores like flower arranging and picking up confetti. It seems like a good arrangement all around, but Sampson the church cat soon tires of the mice’s antics and creates something of a scene during a Sunday service. Luckily, he and the mice still work together to outwit a burglar who comes for the silver. There are quite a lot of words for a very small child to engage with, but older children should enjoy it very much. I find this whole series so charming. This was the first book of the 14, from 1972.

The Church Mouse by Graham Oakley: It is not good for a mouse to be alone. Arthur is lonely as the only mouse resident in the village church, but he has an idea: he proposes to the parson that if he will give all the local mice refuge in the church, they’ll undertake minor chores like flower arranging and picking up confetti. It seems like a good arrangement all around, but Sampson the church cat soon tires of the mice’s antics and creates something of a scene during a Sunday service. Luckily, he and the mice still work together to outwit a burglar who comes for the silver. There are quite a lot of words for a very small child to engage with, but older children should enjoy it very much. I find this whole series so charming. This was the first book of the 14, from 1972.

Cats in May by Doreen Tovey (1959): The sequel is just as good as the original (Cats in the Belfry). Along with feline antics we get the adventures of Blondin the squirrel, whom Tovey and her husband adopted before they started keeping Siamese cats. (He was just as destructive as the pets that came after him, but I had to love his fondness for tea.) Solomon and Sheba appear on the BBC and object in the strongest possible terms when Doreen and Charles try to introduce a third Siamese, a kitten named Samson, to the household. The flu, visits from the rector’s grandson, and periodic troubles with their old farmhouse, including a chimney fire, round out this highly amusing story of life with pets.

Cats in May by Doreen Tovey (1959): The sequel is just as good as the original (Cats in the Belfry). Along with feline antics we get the adventures of Blondin the squirrel, whom Tovey and her husband adopted before they started keeping Siamese cats. (He was just as destructive as the pets that came after him, but I had to love his fondness for tea.) Solomon and Sheba appear on the BBC and object in the strongest possible terms when Doreen and Charles try to introduce a third Siamese, a kitten named Samson, to the household. The flu, visits from the rector’s grandson, and periodic troubles with their old farmhouse, including a chimney fire, round out this highly amusing story of life with pets.

Not all cat books are winners. Here are two that, alas, I cannot recommend:

The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa (2017): This is the fable-like story of Satoru, a single man in his early thirties, and his cat, Nana (named for the shape of his tail, which resembles a Japanese 7). Satoru adopted Nana about five years ago when the cat, a local stray, was hit by a car. Now he needs to find a new owner for his beloved pet. No spoilers here, but really, there are only so many reasons why a young man would need to do this, and readers will likely work it out well before the “big reveal” over halfway through. We bounce between Nana’s perspective, which is quite cutely rendered, and third-person flashbacks to Satoru’s sad history. The author spells out and overstates everything. It’s pretty emotionally manipulative. Pet owners will appreciate Nana’s humor and loyalty (“I’m your cat till the bitter end!”), but I felt like I was being brow-beaten into crying – though I didn’t in the end.

The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa (2017): This is the fable-like story of Satoru, a single man in his early thirties, and his cat, Nana (named for the shape of his tail, which resembles a Japanese 7). Satoru adopted Nana about five years ago when the cat, a local stray, was hit by a car. Now he needs to find a new owner for his beloved pet. No spoilers here, but really, there are only so many reasons why a young man would need to do this, and readers will likely work it out well before the “big reveal” over halfway through. We bounce between Nana’s perspective, which is quite cutely rendered, and third-person flashbacks to Satoru’s sad history. The author spells out and overstates everything. It’s pretty emotionally manipulative. Pet owners will appreciate Nana’s humor and loyalty (“I’m your cat till the bitter end!”), but I felt like I was being brow-beaten into crying – though I didn’t in the end.

I Could Pee on This, Too: And More Poems by More Cats by Francesco Marciuliano (2016): Not a single memorable poem or line in the lot. Seriously. Stick with the original.

My next batch of cat books. Maybe I’ll try to write them up for a Christmas-tide treat.

Whether you are a cat lover or not, do any of these books appeal?

Five Books about Cats

I always used to be more of a dog person than a cat person, even though we had both while I was growing up, but now I’m a dedicated cat owner and have tried out some related reading. You’ll notice I don’t rate any of these five books about cats particularly highly, whereas there have been a number of dog books I’ve given 4 stars (Dog Years by Mark Doty, Ordinary Dogs by Eileen Battersby, A Dog’s Life by Peter Mayle; even books that aren’t necessarily about dogs but reference life with them, like A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas and Travels with Charley by John Steinbeck). What’s with that? Maybe dog lovers don’t have to worry so much about striking a balance between a pet’s standoffishness and affection. Maybe dogs play a larger role in everyday human life and leave a more gaping hole when they shuffle off the canine coil. Still, I enjoyed aspects of or specific passages from each of the following.

The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide

The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide

As a cat-loving freelance writer who aspires to read more literature in translation, I thought from the blurb that this book could not be more perfect for me. I bought it in a charity shop one afternoon and started reading right away. It’s only 140 pages, so I finished within 24 hours, but felt at a distance from the story the whole time. Part of it might be the translation – the translator’s notes at the end explain some useful context about the late 1980s setting, but also conflate the narrator and the author in such a way that the book seems like an artless memoir rather than a novella. But the more basic problem for me is that there’s simply not enough about the cat. There’s plenty of architectural detail about the guesthouse the narrator and his wife rent on the grounds of a mansion, plenty of economic detail about the housing market…but the cat just doesn’t make enough of an impression. I’m at a bit of a loss to explain why this has been such a bestseller. Quite the disappointment.

My rating:

The Fur Person by May Sarton

The Fur Person by May Sarton

I’m a huge fan of May Sarton’s journals – in which various cats play supporting roles – so for a while I’d been hoping to come across a copy of this little novelty book from 1957, a childish fable about a tomcat who transforms from a malnourished Cat-About-Town to a spoiled Gentleman Cat. Luckily I managed to find a copy of this one plus the Lessing (see below) in the Nature section at Book Thing of Baltimore. In a preface to the 1978 edition Sarton reveals that Tom Jones was, indeed, a real cat, a stray she and her partner Judy Matlack adopted when they lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Wonderful coincidence: when they were on sabbatical in the early 1950s, they sublet the place to the Nabokovs, who looked after Tom while they were away!

I found this a bit lightweight overall, and the whole idea of a ‘fur person’ is a little strange – don’t we love cats precisely because they’re not people? Still, I enjoyed the proud cat’s Ten Commandments (e.g. “II. A Gentleman Cat allows no constraint of his person … III. A Gentleman Cat does not mew except in extremity”) and spotted my own domestic situation in this description: “while she [‘Gentle Voice’ = Judy] was away the other housekeeper [= Sarton] was sometimes quite absent-minded and even forgot his lunch once or twice because she sat for hours and hours in front of a typewriter, tapping out messages with her fingers.” The black-and-white illustrations by David Canright are a highlight.

I found this a bit lightweight overall, and the whole idea of a ‘fur person’ is a little strange – don’t we love cats precisely because they’re not people? Still, I enjoyed the proud cat’s Ten Commandments (e.g. “II. A Gentleman Cat allows no constraint of his person … III. A Gentleman Cat does not mew except in extremity”) and spotted my own domestic situation in this description: “while she [‘Gentle Voice’ = Judy] was away the other housekeeper [= Sarton] was sometimes quite absent-minded and even forgot his lunch once or twice because she sat for hours and hours in front of a typewriter, tapping out messages with her fingers.” The black-and-white illustrations by David Canright are a highlight.

My rating:

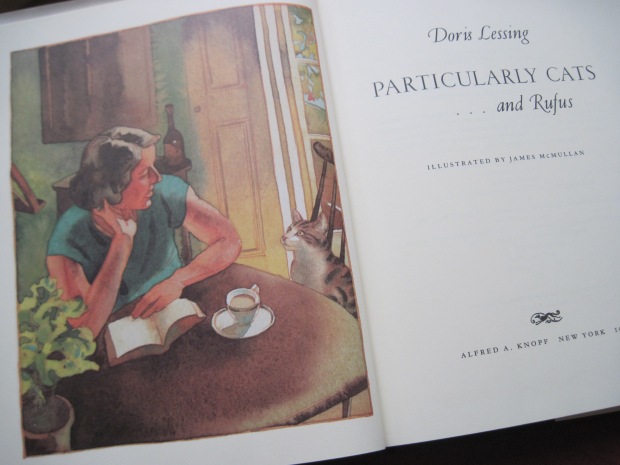

Particularly Cats…And Rufus by Doris Lessing

Particularly Cats…And Rufus by Doris Lessing

A book about cats that I would almost hesitate to recommend to cat lovers: it contains many a scene of kitty carnage, as well as some unenlightened resistance to spaying and neutering. Lessing grew up on a farm in Zimbabwe that was at one point overrun with about 40 cats. Her mother went away, expecting her father to have ‘taken care of them’ by the time she got back. He tried chloroform to start with, but it was too slow and ineffective; in the end he rounded them all up in a room and got out his WWI revolver. And that’s not the end of it; even into her adulthood in England Lessing balked at taking female cats in for surgery so would find occasionally herself saddled with unwanted litters of kittens that they decided had to be drowned. It’s really a remarkably unsentimental record of her dealings with cats.

That’s not to say there weren’t some cats she willingly and lovingly kept as pets, particularly a pair of rival females known simply as “black cat” and “grey cat,” and later a stray named Rufus who adopted her. But even with cherished felines she comes across as tough: “Anyway, she had to be killed and I decided that to keep cats in London was a mistake” or “I smacked grey cat” for bullying the black one. The very fact of not giving the pair names certainly quashes any notion of her as some cuddly cat lady. All the same, she was a dutiful nurse when black cat and Rufus fell ill. The book ends on a repentant note: “Knowing cats, a lifetime of cats, what is left is a sediment of sorrow quite different from that due to humans: compounded of pain for their helplessness, of guilt on behalf of us all.”

My favorite thing about the book is the watercolor illustrations by James McMullan.

My rating:

The Unadulterated Cat: A Campaign for Real Cats by Terry Pratchett

The Unadulterated Cat: A Campaign for Real Cats by Terry Pratchett

Like Douglas Adams or Monty Python, Terry Pratchett is, alas, a representative of the kind of British humor I just don’t get. But I rather enjoyed this small novelty book (bought for my husband for Christmas) all the same. For Pratchett, a “Real” cat is a non-pampered, tough-as-nails outdoor creature that hunts and generally does its own thing but also knows how to wrap its human servants around its paws. I like his idea of “cat chess” as a neighborhood-wide feline game of strategy, moving between carefully selected vantage points to keep an eye on the whole road yet avoid confrontation with other cats. It’s certainly true on our street. And this is quite a good summary of what cats do and why we put up with them:

What other animal gets fed, not because it’s useful, or guards the house, or sings, but because when it does get fed it looks pleased? And purrs. The purr is very important. It’s the purr that makes up for the Things Under the Bed, the occasional pungency, the 4 a.m. yowl.

My rating:

On Cats by Charles Bukowski

On Cats by Charles Bukowski

“In my next life I want to be a cat. To sleep 20 hours a day and wait to be fed. To sit around licking my ass.” I’d never read anything else by Bukowski, so I wasn’t sure quite what to expect from this book, which is mostly composed of previously unpublished poems and short prose pieces about the author’s multiple cats. The tone is an odd mixture of gruff and sentimental. Make no mistake: his cats were all Real cats, in line with the Pratchett model. A white Manx cat, for instance, had been shot, run over, and had his tail cut off. Another was named Butch Van Gogh Artaud Bukowski. You wouldn’t mess with a cat with a macho name like that, would you? My favorite passage is from “War Surplus,” about an exchange he and his wife had with a store clerk:

“what will the cats do if there is an explosion?”

“lady, cats are different than we are, they are of a lower order.”

“I think cats are better than we are,” I said.

the clerk looked at me. “we don’t have gas masks for cats.”

My rating:

This past Saturday I browsed the charity shops and found a short story collection I’ve been interested in reading, but otherwise just spent hours in Stamford’s library looking through recent issues of the Times Literary Supplement and The Bookseller and reading from the stack of novellas I’d brought with me. I read four in one sitting because all were shorter than 50 pages long: two obscure classics and two nature books.

This past Saturday I browsed the charity shops and found a short story collection I’ve been interested in reading, but otherwise just spent hours in Stamford’s library looking through recent issues of the Times Literary Supplement and The Bookseller and reading from the stack of novellas I’d brought with me. I read four in one sitting because all were shorter than 50 pages long: two obscure classics and two nature books.

Trees have been a surprise recurring theme in my 2018 reading. This spare allegory from a Provençal author is all about the difference one person can make. The narrator meets a shepherd and beekeeper named Elzéard Bouffier who plants as many acorns as he can; “it struck him that this part of the country was dying for lack of trees, and having nothing much else to do he decided to put things right.” Decades pass and two world wars do their worst, but very little changes in the countryside. Old Bouffier has led an unassuming but worthwhile life.

Trees have been a surprise recurring theme in my 2018 reading. This spare allegory from a Provençal author is all about the difference one person can make. The narrator meets a shepherd and beekeeper named Elzéard Bouffier who plants as many acorns as he can; “it struck him that this part of the country was dying for lack of trees, and having nothing much else to do he decided to put things right.” Decades pass and two world wars do their worst, but very little changes in the countryside. Old Bouffier has led an unassuming but worthwhile life. There’s not very much to this story, though I appreciated the message about doing good even if you won’t get any recognition or even live to see the fruits of your labor. What’s most interesting about it is the publication history: it was commissioned by Reader’s Digest for a series on “The Most Extraordinary Character I Ever Met,” and though the magazine accepted it with rapture, there was belated outrage when they realized it was fiction. It was later included in a German anthology of biography, too! No one recognized it as a fable; this became a sort of literary in-joke, as Giono’s daughter Aline reveals in a short afterword.

There’s not very much to this story, though I appreciated the message about doing good even if you won’t get any recognition or even live to see the fruits of your labor. What’s most interesting about it is the publication history: it was commissioned by Reader’s Digest for a series on “The Most Extraordinary Character I Ever Met,” and though the magazine accepted it with rapture, there was belated outrage when they realized it was fiction. It was later included in a German anthology of biography, too! No one recognized it as a fable; this became a sort of literary in-joke, as Giono’s daughter Aline reveals in a short afterword.

You probably know the basic plot even if you’ve never read the story. Hired as the fourth scrivener in a Wall Street office of law-copyists, Bartleby seems quietly efficient until one day he mildly refuses to do the work requested of him. “I prefer not to” becomes his refrain. First he stops proofreading his copies, and then he declines to do any writing at all. (More and more these days, I find I have the same can’t-be-bothered attitude as Bartleby!) As the employer/narrator writes, “a certain unconscious air … of pallid haughtiness … positively awed me into my tame compliance with his eccentricities.” Farce ensues as he finds himself incapable of getting rid of Bartleby, even after he goes to the extreme of changing the premises of his office. Three times he even denies knowing Bartleby, but still the man is a thorn in his flesh, a nuisance turned inescapable responsibility. A glance at the introduction by Harold Beaver tells me I’m not the first to make such Christian parallels. (This was the first Melville I’ve read since an aborted attempt on Moby-Dick during college.)

You probably know the basic plot even if you’ve never read the story. Hired as the fourth scrivener in a Wall Street office of law-copyists, Bartleby seems quietly efficient until one day he mildly refuses to do the work requested of him. “I prefer not to” becomes his refrain. First he stops proofreading his copies, and then he declines to do any writing at all. (More and more these days, I find I have the same can’t-be-bothered attitude as Bartleby!) As the employer/narrator writes, “a certain unconscious air … of pallid haughtiness … positively awed me into my tame compliance with his eccentricities.” Farce ensues as he finds himself incapable of getting rid of Bartleby, even after he goes to the extreme of changing the premises of his office. Three times he even denies knowing Bartleby, but still the man is a thorn in his flesh, a nuisance turned inescapable responsibility. A glance at the introduction by Harold Beaver tells me I’m not the first to make such Christian parallels. (This was the first Melville I’ve read since an aborted attempt on Moby-Dick during college.)

Crumley is an underappreciated Scottish nature writer. Here he tells the tale of a pair of mute swans on a loch in Highland Perthshire. He followed their relationship with great interest over a matter of years. First he noticed that their nest had been robbed, twice within a few weeks, and realized otters must be to blame. Then, although it’s a truism that swans mate for life, he observed the cob (male) leaving the pen (female) for another! Crumley was overtaken with sympathy for the abandoned swan and got to feed her by hand and watch her fall asleep. “To suggest there was true communication between us would be outrageous, but I believe she regarded me as benevolent, which was all I ever asked of her,” he writes. Two years later he learns the end of her story. A pleasant ode to fleeting moments of communion with nature.

Crumley is an underappreciated Scottish nature writer. Here he tells the tale of a pair of mute swans on a loch in Highland Perthshire. He followed their relationship with great interest over a matter of years. First he noticed that their nest had been robbed, twice within a few weeks, and realized otters must be to blame. Then, although it’s a truism that swans mate for life, he observed the cob (male) leaving the pen (female) for another! Crumley was overtaken with sympathy for the abandoned swan and got to feed her by hand and watch her fall asleep. “To suggest there was true communication between us would be outrageous, but I believe she regarded me as benevolent, which was all I ever asked of her,” he writes. Two years later he learns the end of her story. A pleasant ode to fleeting moments of communion with nature.  In 2011 Macfarlane set out to recreate a journey through South Dorset that he’d first undertaken with the late Roger Deakin in 2005, targeting the sunken paths of former roadways. This is not your average nature or travel book, though; it’s much more fragmentary and poetic than you’d expect from a straightforward account of a journey through the natural world. I thought the stream-of-consciousness style overdone, and got more out of the song about the book by singer-songwriter Anne-Marie Sanderson. (Her Book Songs, Volume 1 EP, which has been one of my great discoveries of the year, is available to listen to and purchase on

In 2011 Macfarlane set out to recreate a journey through South Dorset that he’d first undertaken with the late Roger Deakin in 2005, targeting the sunken paths of former roadways. This is not your average nature or travel book, though; it’s much more fragmentary and poetic than you’d expect from a straightforward account of a journey through the natural world. I thought the stream-of-consciousness style overdone, and got more out of the song about the book by singer-songwriter Anne-Marie Sanderson. (Her Book Songs, Volume 1 EP, which has been one of my great discoveries of the year, is available to listen to and purchase on

The Only Story by Julian Barnes: A familiar story: a May–December romance fizzles out. A sad story: an idealistic young man who swears he’ll never be old and boring has to face that this romance isn’t all he wanted it to be. A love story nonetheless. Paul met 48-year-old Susan, a married mother of two, at the local tennis club when he was 19. The narrative is partly the older Paul’s way of salvaging what happy memories he can, but also partly an extended self-defense. Barnes takes what could have been a dreary and repetitive story line and makes it an exquisitely plangent progression: first-person into second-person into third-person. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity.

The Only Story by Julian Barnes: A familiar story: a May–December romance fizzles out. A sad story: an idealistic young man who swears he’ll never be old and boring has to face that this romance isn’t all he wanted it to be. A love story nonetheless. Paul met 48-year-old Susan, a married mother of two, at the local tennis club when he was 19. The narrative is partly the older Paul’s way of salvaging what happy memories he can, but also partly an extended self-defense. Barnes takes what could have been a dreary and repetitive story line and makes it an exquisitely plangent progression: first-person into second-person into third-person. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity.

Florida by Lauren Groff: Two major, connected threads in this superb story collection are ambivalence about Florida, and ambivalence about motherhood. There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout, with environmental catastrophe an underlying threat. Set-ups vary in scope from almost the whole span of a life to one scene. A dearth of named characters emphasizes just how universal the scenarios and emotions are. Groff’s style is like a cross between Karen Russell’s Swamplandia! and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and her unexpected turns of phrase jump off the page. A favorite was “Above and Below,” in which a woman slips into homelessness. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant. Any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece.

Florida by Lauren Groff: Two major, connected threads in this superb story collection are ambivalence about Florida, and ambivalence about motherhood. There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout, with environmental catastrophe an underlying threat. Set-ups vary in scope from almost the whole span of a life to one scene. A dearth of named characters emphasizes just how universal the scenarios and emotions are. Groff’s style is like a cross between Karen Russell’s Swamplandia! and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and her unexpected turns of phrase jump off the page. A favorite was “Above and Below,” in which a woman slips into homelessness. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant. Any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece.

The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is just an Italian teacher, though as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he would follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts. We follow Pinch through the rest of his life, a sad one of estrangement, loss and misunderstandings – but ultimately there’s a sly triumph in store for the boy who was told that he’d never make it as an artist. Rachman jets between lots of different places – Rome, New York City, Toronto, rural France, London – and ropes in quirky characters in the search for an identity and a place to belong. This is a rewarding story about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents, and the legacy of artists in a fickle market.

The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is just an Italian teacher, though as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he would follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts. We follow Pinch through the rest of his life, a sad one of estrangement, loss and misunderstandings – but ultimately there’s a sly triumph in store for the boy who was told that he’d never make it as an artist. Rachman jets between lots of different places – Rome, New York City, Toronto, rural France, London – and ropes in quirky characters in the search for an identity and a place to belong. This is a rewarding story about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents, and the legacy of artists in a fickle market.

The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan: Some of the best medical writing from a layman’s perspective I’ve ever read. Donlan, a Brighton-area video games journalist, was diagnosed with (relapsing, remitting) multiple sclerosis in 2014. “I think sometimes that early MS is a sort of tasting menu of neurological disease,” Donlan wryly offers. He approaches his disease with good humor and curiosity, using metaphors of maps to depict himself as an explorer into uncharted territory. The accounts of going in for an MRI and a round of chemotherapy are excellent. Short interludes also give snippets from the history of MS and the science of neurology in general. What’s especially nice is how he sets up parallels with his daughter’s early years. My frontrunner for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize so far.

The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan: Some of the best medical writing from a layman’s perspective I’ve ever read. Donlan, a Brighton-area video games journalist, was diagnosed with (relapsing, remitting) multiple sclerosis in 2014. “I think sometimes that early MS is a sort of tasting menu of neurological disease,” Donlan wryly offers. He approaches his disease with good humor and curiosity, using metaphors of maps to depict himself as an explorer into uncharted territory. The accounts of going in for an MRI and a round of chemotherapy are excellent. Short interludes also give snippets from the history of MS and the science of neurology in general. What’s especially nice is how he sets up parallels with his daughter’s early years. My frontrunner for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize so far.

Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber: The author grew up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber, outside Cincinnati in the 1960s to 70s. This and Woodie’s other most notable design, Sander Hall, a controversial tower-style dorm at the University of Cincinnati that was later destroyed in a controlled explosion, serve as powerful metaphors for her dysfunctional family life. Woodie is such a fascinating, flawed figure. Garber endured sexual and psychological abuse yet likens him to Odysseus, the tragic hero of his own life. She connected with him over Le Corbusier’s designs, but it was impossible for a man born in the 1910s to understand his daughter’s generation. This definitely is not a boring tome just for architecture buffs. It’s a masterful memoir for everyone.

Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber: The author grew up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber, outside Cincinnati in the 1960s to 70s. This and Woodie’s other most notable design, Sander Hall, a controversial tower-style dorm at the University of Cincinnati that was later destroyed in a controlled explosion, serve as powerful metaphors for her dysfunctional family life. Woodie is such a fascinating, flawed figure. Garber endured sexual and psychological abuse yet likens him to Odysseus, the tragic hero of his own life. She connected with him over Le Corbusier’s designs, but it was impossible for a man born in the 1910s to understand his daughter’s generation. This definitely is not a boring tome just for architecture buffs. It’s a masterful memoir for everyone.

Bookworm by Lucy Mangan: Mangan takes us along on a nostalgic chronological tour through the books she loved most as a child and adolescent. No matter how much or how little of your early reading overlaps with hers, you’ll appreciate her picture of the intensity of children’s relationship with books – they can completely shut out the world and devour their favorite stories over and over, almost living inside them, they love and believe in them so much – and her tongue-in-cheek responses to them upon rereading them decades later. There are so many witty lines that it doesn’t really matter whether you give a fig about the particular titles she discusses or not. A delightful paean to the joys of being a lifelong reader; recommended to bibliophiles and parents trying to make bookworms out of their children.

Bookworm by Lucy Mangan: Mangan takes us along on a nostalgic chronological tour through the books she loved most as a child and adolescent. No matter how much or how little of your early reading overlaps with hers, you’ll appreciate her picture of the intensity of children’s relationship with books – they can completely shut out the world and devour their favorite stories over and over, almost living inside them, they love and believe in them so much – and her tongue-in-cheek responses to them upon rereading them decades later. There are so many witty lines that it doesn’t really matter whether you give a fig about the particular titles she discusses or not. A delightful paean to the joys of being a lifelong reader; recommended to bibliophiles and parents trying to make bookworms out of their children.