Final Reading Statistics for 2025 & Goals for 2026

Happy New Year! We went to a neighbours’ party again this year and played silly games and chased their kittens until 1:30 a.m. It was a fun, low-key way to see in 2026.

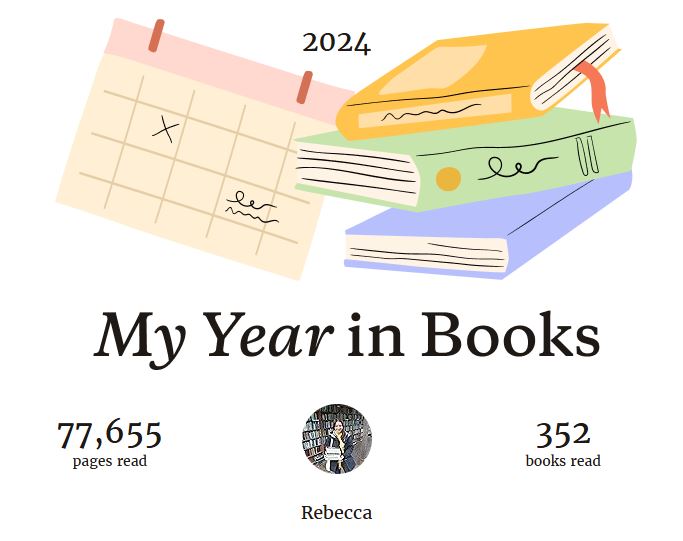

I read 313 books last year. (2024’s total of 352 will never be topped!) Initially, I set a goal of 350, but by midyear I downgraded it to 300 and it was easy to reach. I can’t pinpoint a particular reason for the decline. In general, I felt like I was chasing my tail all year, despite having less work on than ever (but increased volunteering commitments). Often, I struggled with fatigue or being on the verge of illness. What a fun guessing game: is it long Covid or perimenopause?

Goodreads was glitchy for me all year, randomly counting books two or three times and falsely inflating my total by a whole extra 33 books at one point. It also has a lot of annoying, automatically generated book records that duplicate ISBNs or add the publisher to the title field. So I’m thinking about moving over to StoryGraph this year – I just imported my Goodreads library – though I always quail at learning new online systems. It would also be the next logical step in divesting from Am*zon.

The year that was…

2025’s notable happenings:

- Twice assessing the ‘proper’ (published) books as a McKitterick Prize judge

- Adopting crazy Benny (though that was after losing our precious Alfie)

- Acquiring a secondhand electric car for the household

- Holidays in Hay-on-Wye; the Outer Hebrides; Suffolk; Berlin and Lübeck, Germany

- A summer visit from my sister and brother-in-law

- Having the windows and door replaced in the back of our house; and the hall and stairwell/landing redecorated

- I got ever more into gin and cocktails, with tastings in Abingdon and Wantage (and in December I led two informal tastings for friends). I also acquired the taste for rum!

The reading statistics, as compared to 2024:

Fiction: 54.7% (↑3.3%)

Nonfiction: 31.6% (↓0.2%)

Poetry: 13.7% (↓3.1%)

Female author: 67.7% (↓0.2%)

Lydi Conklin was one of 10 nonbinary authors I read from this year. Had I read their novel earlier, this would have made it into my Cover Love post!

Nonbinary author: 3.2% (↑2.1%)

BIPOC author: 18.5% (↑0.1%)

How to get it to 25% or more??

LGBTQ: 20.4% (↓1.1%)

(Author’s identity or a major theme in the work.) It’s the first time this has decreased since 2021, but I’m still pleased with the figure overall.

Work in translation: 9.6% (↑3.6%)

Going the right way with this trend! 10% seems like a good minimum to aim for. I find I have to make a conscious effort by accepting translated review copies or picking them off my shelves to tie in with particular reading challenges.

German (6) – mainly because of our trip in September

French (5)

Swedish (4)

Korean (3)

Italian (2)

Italian (2)

Japanese (2)

Spanish (2)

Chinese (1)

Dutch (1)

Norwegian (1)

Polish (1)

Portuguese (1)

Russian (1)

2025 (or pre-release 2026) books: 55.6% (↑3.2%)

Backlist: 44.4%

But a lot of that ‘backlist’ stuff was still from the 2020s; I only read eight pre-1950 books, the oldest being Diary of a Nobody from 1892.

E-books: 35.5% (↑3.4%)

Print books: 64.5%

I almost exclusively read e-books for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness reviews. The number of overall Shelf Awareness reviews will be decreasing because of changes to their publishing model, so this figure may well change by next year.

Rereads: 11, vs. last year’s 18

I managed nearly one a month. Like last year, three of my rereads ended up being among my most memorable reading experiences of the year, so I should really reread more often.

And, courtesy of Goodreads:

- 69,616 pages read

- Average book length: 221 pages (just one off of last year’s 220; in previous years it has always been 217–225, driven downward by poetry collections and novellas)

- Average rating for 2025: 6 (identical to the last three years)

Where my books came from for the whole year, compared to 2024:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 33.9% (↓10.9%)

- Public library: 18.8% (↑0.4%)

- Free (gifts, giveaways, Little Free Library/free bookshop, from friends or neighbours): 15.3% (↑2.9%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley, Edelweiss or BookSirens: 15% (↑7.2%)

- Secondhand purchase: 12.8% (↑1.3%)

- New purchase (often at a bargain price; includes Kindle purchases): 2.6% (↓0.5%)

- University library: 1.3% (↓0.7%)

- Other (church theological library): 0.3% (↑0.3%)

I’m pleased that 30.3% of my reading was from my own shelves, versus last year’s 24%. It looks like I mainly achieved this through a reduction in review copies. In 2026, I’d like to read even more backlist material from my own shelves (including rereads). This will be a particular focus in January, and then I’ll plan how to incorporate it for the rest of the year.

I have an absurd number of review books to catch up on (42), some stretching back to 2022 – the year of my mother’s death, which put me off my stride in many ways – as well as part-read books (116) to get real about and either finish or call DNFs and clear from my shelves. Dealing with these can be part of the reading-from-my-shelves initiative.

What trends did you see in your year’s reading? What is your plan for 2026?

Final Reading Statistics for 2024

Happy New Year! Even though we were out at neighbours’ until 2:45 a.m. (who are these party animals?!), I’m feeling bright-eyed and bushy-tailed today and looking forward to a special brunch at our favourite Newbury establishment. Despite all evidence to the contrary in the news – politically, environmentally, internationally – I’m choosing to be optimistic about what 2025 will hold. What hope I have comes from community and grassroots efforts.

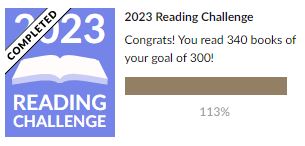

In other good news, 2024 saw my highest reading total yet! (My usual average, as in 2019–21 and 2023, is 340.) Last year I challenged myself to read 350 books and I managed it easily, even though at one point in the middle of the year I was far behind and it didn’t look possible.

Reading a novella a day in November was certainly a major factor in meeting my goal. I also tend to prioritize poetry collections and novellas for my Shelf Awareness reviewing, and in general I consider it a bonus if a book is closer to 200 pages than 300+.

The statistics

Fiction: 51.4%

Nonfiction: 31.8% (similar to last year’s 31.2%)

Poetry: 16.8% (identical to last year!)

Female author: 67.9% (close to last year’s 69.7%)

Male author: 29.6%

Nonbinary author: 1.1%

Multiple genders (anthologies): 1.4%

BIPOC author: 18.4%

This has dropped a bit compared to previous years’ 22.4% (2023), 20.7% (2022), and 18.5% (2021). My aim will be to make it 25% or more.

LGBTQ: 21.6%

(Based on the author’s identity or a major theme in the work.) This has been increasing from 11.8% (2021), 8.8% (2022), and 18.2% (2023). I’m pleased!

Work in translation: 6%

I read only 21 books in translation last year, alas. This is an unfortunate drop from the previous year’s 10.6%. I do prefer to be closer to 10%, so I will need to make a conscious effort to borrow translated books and incorporate them in my challenges.

French (7)

German (4)

Norwegian (3)

Spanish (3)

Italian (1)

Latvian (1) – a new language for me to have read from

Swedish (1)

+ Misc. in a story anthology

2024 (or pre-release 2025) books: 52.3% (up from 44.7% last year)

Backlist: 47.7%

But a lot of that ‘backlist’ stuff was still from the 2020s; I only read five pre-1950 books, the oldest being Howards End and Kilmeny of the Orchard, both from 1910. I should definitely pick up something from the 19th century or earlier next year!

E-books: 32.1% (up from 27.4% last year)

Print books: 67.9%

I almost exclusively read e-books for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness reviews.

Rereads: 18

I doubled last year’s 9! I’m really happy with this 1.5/month average. Three of my rereads ended up being among my most memorable reading experiences for the year.

And, courtesy of Goodreads:

Average book length: 220 pages (in previous years it has been 217 and 225)

Average rating for 2024: 3.6 (identical to the last two years)

Where my books came from for the whole year, compared to 2023:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 44.8% (↑1.3%)

- Public library: 18.4% (↓5.7%)

- Secondhand purchase: 11.5% (↑1.7%)

- Free (giveaways, Little Free Library/free bookshop, from friends or neighbours): 9.8% (↑3.9%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley, Edelweiss, BookSirens or Project Gutenberg: 8.8% (↑2%)

- Gifts: 2.6% (↓1.5%)

- New purchase (often at a bargain price; includes Kindle purchases): 2.1% (↓2.6%)

- University library: 2% (↓1.2%)

So, like last year, nearly a quarter of my reading (24%) was from my own shelves. I’d like to make that more like a third to half, which would be better achieved by a reduction in the number of review copies rather than a drop in my library borrowing. It would also ensure that I read more backlist books.

What trends and changes did you see in your year’s reading?

Final Reading Statistics for 2023

In 2022 my reading total dipped to 300, whereas in 2023 I was back up to what seems to be my natural limit of 340 books (as 2019–21 also proved).

The statistics

Fiction: 52.1%

Nonfiction: 31.2%

Poetry: 16.8%

(Poetry is up by nearly 3% and fiction and nonfiction down by a percent or so each compared to last year. I attribute this to specializing in poetry reviews for Shelf Awareness.)

Female author: 69.7%

Male author: 27.6%

Nonbinary author: 2.1%

Multiple genders (anthologies): 0.6%

(I always read more from women than from men, but was surprised to see that the percentage by men rose by 4.6% last year.)

BIPOC author: 22.4%

(The third time I have specifically tracked this figure. I’m pleased that it’s increased year on year: 18.5%, then 20.7%. I will continue to aim at 25% or more.)

LGBTQ: 18.2%

(This is a new category for me. I define it by the identity of the author and/or a major theme in the work; just having a secondary character who is gay wouldn’t count. I retrospectively looked at 2021 and 2022, which would have been at 11.8% and 8.8%.)

Work in translation: 10.6%!

(I’m delighted with this figure because the past two years were at just 5% and 8.7% and my aim was to be close to 10%. Most popular languages: Spanish (10), French (9) and Swedish (4); German (3), Italian (3), Danish (2), Dutch (2), Korean (1), Polish (1) and Welsh (1) were also represented.)

Backlist: 55.3%

2023 (or 2024 pre-release) books: 44.7%

(This is not too bad, although 17.9% of the ‘backlist’ stuff was from 2021 or 2022, so fairly recent releases I was catching up on from review copies, the library or in e-book form. My oldest reads were both from 1897, Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham and De Profundis by Oscar Wilde.)

E-books: 27.4%

Print books: 72.6%

(On par with last year. I almost exclusively read e-books for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness reviews.)

Rereads: 9

(Compared to 12 each of the past two years; at least one per month would be a good aim.)

Where my books came from for the whole year, compared to last year:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 43.5% (↑1.5%)

- Public library: 24.1% (↓5.9%)

- Secondhand purchase: 10% (↑3.3%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley or Edelweiss: 6.8% (↓0.2%)

- Free (giveaways, Little Free Library/free bookshop, from friends or neighbours): 5.9% (↑3.3%)

- Gifts: 4.1% (↑0.1%)

- University library: 3.2% (↑0.9%)

- New purchase (often at a bargain price): 2.1% (↓2.6%)

- Borrowed: 0.3% (↓0.4%)

So nearly a quarter of my reading (22.1%) was from my own shelves. I’d like to make it more like 33–50%, achieved by a drop in review copies rather than library borrowing.

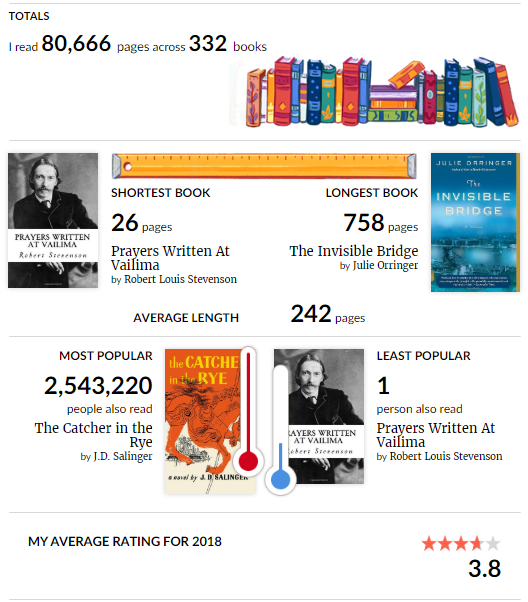

Additional statistics courtesy of Goodreads:

73,861 pages read

Average book length: 217 pages (down from 225 last year; thank you, novellas and poetry)

Average rating for 2022: 3.6 (identical to last year)

Reading Statistics for the First Half of 2020, Including Where My Books Came From

Almost halfway through the year: how am I doing on the reading goals I set for myself? Pretty well!

- It might not look like it from the statistics below, but I have drastically cut down on the number of review copies I’m requesting or accepting from publishers. (This time last year they made up 43% of my reading.)

- I’ve reread nine books so far, which is more than I can remember doing in any other year – and I intend to continue prioritizing rereads in the remaining months.

- Thanks to COVID-19, over the past few months I have been reading a lot less from the libraries I use and, consequently, more from my own shelves. This might continue into next month but thereafter, when libraries reopen, my borrowing will increase.

- I’ve also bought many more new books than is usual for me, to directly support authors and independent bookshops.

- I’m not managing one doorstopper per month (I’ve only done May so far, though I have a few lined up for June‒August), but I am averaging at least one classic per month (I only missed January, but made up for it with multiple in two other months).

- On literature in translation, I’m doing better: it’s made up 9.7% of my reading, versus 8.1% in 2019.

The breakdown:

Fiction: 57.6%

Nonfiction: 36.3%

Poetry: 6.1%

(This time last year I’d read exactly equal numbers of fiction and nonfiction books. Fiction seems to be winning this year. Poetry is down massively: last June it was at 15.4%.)

Male author: 34.7%

Female author: 63.5%

Anthologies with pieces by authors of multiple genders: 1.8%

(No non-binary authors so far this year. Even more female-dominated than last year.)

E-books: 12.7%

Print books: 87.3%

(E-books have crept up a bit since last year due to some publishers only offering PDF review copies during the pandemic, but I have still been picking up many more print books.)

I always find it interesting to look back at where my books come from. Here are the statistics for the year so far, in percentages (not including the books I’m currently reading, DNFs or books I only skimmed):

- Free print or e-copy from the publisher: 25.5%

- Public library: 21.2%

- Free, e.g. from Book Thing of Baltimore, local swap shop or free mall bookshop: 16.4%

- Secondhand purchase: 10.3%

- Downloaded from NetGalley or Edelweiss: 8.5%

- New purchase: 7.3%

- Gifts: 5.4%

- University library: 5.4%

How are you doing on any reading goals you set for yourself?

Where do you get most of your books from?

Other 2019 Superlatives and Some Statistics

My best discoveries of the year: The poetry of Tishani Doshi; Penelope Lively and Elizabeth Strout (whom I’d read before but not fully appreciated until this year); also, the classic nature writing of Edwin Way Teale.

The authors I read the most by this year: Margaret Atwood and Janet Frame (each: 2 whole books plus parts of 2 more), followed by Doris Lessing (2 whole books plus part of 1 more), followed by Miriam Darlington, Paul Gallico, Penelope Lively, Rachel Mann and Ben Smith (each: 2 books).

Debut authors whose next work I’m most looking forward to: John Englehardt, Elizabeth Macneal, Stephen Rutt, Gail Simmons and Lara Williams.

My proudest reading achievement: A 613-page novel in verse (Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile by Alice Jolly) + 2 more books of over 600 pages (East of Eden by John Steinbeck and Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese).

Best book club selection: Red Dust Road by Jackie Kay was our first nonfiction book and received our highest score ever.

Some best first lines encountered this year:

“What can you say about a twenty-five-year old girl who died?” (Love Story by Erich Segal)

“What can you say about a twenty-five-year old girl who died?” (Love Story by Erich Segal)- “The women of this family leaned towards extremes” (Away by Jane Urquhart)

- “The day I returned to Templeton steeped in disgrace, the fifty-foot corpse of a monster surfaced in Lake Glimmerglass.” (from The Monsters of Templeton by Lauren Groff)

The downright strangest book I read this year: Lanny by Max Porter

The 2019 books everybody else loved (or so it seems), but I didn’t: Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner, The Topeka School by Ben Lerner, Underland by Robert Macfarlane, The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and The Horse by Charlie Mackesy, Three Women by Lisa Taddeo and The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

The year’s major disappointments: Cape May by Chip Cheek, We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast by Jonathan Safran Foer, Letters to the Earth: Writing to a Planet in Crisis, ed. Anna Hope et al., Bowlaway by Elizabeth McCracken, Rough Magic: Riding the World’s Loneliest Horse Race by Lara Prior-Palmer, The Lager Queen of Minnesota by J. Ryan Stradal, The Knife’s Edge by Stephen Westaby and Frankissstein by Jeanette Winterson

The year’s major disappointments: Cape May by Chip Cheek, We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast by Jonathan Safran Foer, Letters to the Earth: Writing to a Planet in Crisis, ed. Anna Hope et al., Bowlaway by Elizabeth McCracken, Rough Magic: Riding the World’s Loneliest Horse Race by Lara Prior-Palmer, The Lager Queen of Minnesota by J. Ryan Stradal, The Knife’s Edge by Stephen Westaby and Frankissstein by Jeanette Winterson

The worst book I read this year: Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach

Some statistics on my 2019 reading:

Fiction: 45.4%

Nonfiction: 43.4%

Poetry: 11.2%

(As usual, fiction and nonfiction are neck and neck. I read a bit more poetry this year than last.)

Male author: 39.4%

Female author: 58.9%

Nonbinary author (the first time this category has been applicable for me): 0.85%

Multiple genders (anthologies): 0.85%

(I’ve said this the past three years: I find it interesting that female authors significantly outweigh male authors in my reading; I have never consciously set out to read more books by women.)

E-books: 10.3%

Print books: 89.7%

(My e-book reading has been declining year on year, partially because I’ve cut back on the reviewing gigs that involve only reading e-books and partially because I’ve done less traveling; also, increasingly, I find that I just prefer to sit down with a big stack of print books.)

Work in translation: 7.2%

(Lower than I’d like, but better than last year’s 4.8%.)

Where my books came from for the whole year:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 36.8%

- Public library: 21.3%

- Secondhand purchase: 13.8%

- Free (giveaways, The Book Thing of Baltimore, the free mall bookshop, etc.): 9.2%

- Downloaded from NetGalley, Edelweiss or Project Gutenberg: 7.8%

- Gifts: 4.3%

- University library: 2.9%

- New purchase (usually at a bargain price): 2.9%

- Church theological library: 0.8%

- Borrowed: 0.2%

(Review copies accounted for over a third of my reading; I’m going to scale way back on this next year. My library reading was similar to last year’s; my e-book reading decreased in general; I read more books that I either bought new or got for free.)

Number of unread print books in the house: 440

(Last thing I knew the figure was more like 300, so this is rather alarming. I blame the free mall bookshop, where I volunteer every Friday. Most weeks I end up bringing home at least a few books, but it’s often a whole stack. Surely you understand. Free books! No strings attached!)

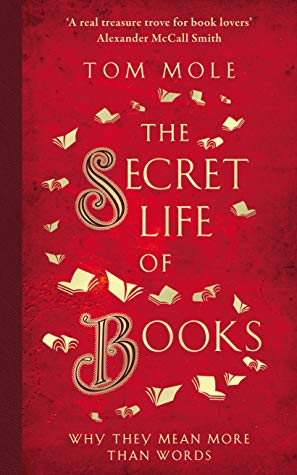

The Secret Life of Books by Tom Mole

If you’re like me and author Tom Mole, the first thing you do in any new acquaintance’s house is to scrutinize their bookshelves, whether openly or surreptitiously. You can learn all kinds of surprising things about what someone is interested in, and holds dear, from the books on display. (And if they don’t have any books around, should you really be friends?)

If you’re like me and author Tom Mole, the first thing you do in any new acquaintance’s house is to scrutinize their bookshelves, whether openly or surreptitiously. You can learn all kinds of surprising things about what someone is interested in, and holds dear, from the books on display. (And if they don’t have any books around, should you really be friends?)

Mole runs the Centre for the History of the Book at the University of Edinburgh, where he is a professor of English Literature and Book History. His specialist discipline and this book’s subtitle – “Why They Mean More than Words” – are clues that here he’s concerned with books more as physical and cultural objects than as containers of knowledge and stories:

“reading them is only one of the things we do with books, and not always the most significant. For a book to signal something about you, you don’t necessarily need to have read it.”

From the papyrus scroll to the early codex, from a leather-bound first edition to a mass-market paperback, and from the Kindle to the smartphone reading app, Mole asks how what we think of as a “book” has changed and what our different ways of accessing and possessing books say about us. He examines the book as a basis of personal identity and relationships with other people. His learned and digressive history of the book contains many pleasing pieces of trivia about authors, libraries and bookshops, making it a perfect gift for bibliophiles. I also enjoyed the three “interludes,” in which he explores three paintings that feature books.

There are a lot of talking points here for book lovers. Here are a few:

- Are you a true collector, or merely an “accumulator” of books? (Mole is the latter, as am I. “I have a few modest antiquarian volumes, but most of my books are paperbacks … I was the first in my immediate family to go to university, and I suspect the books on my shelves reassure me that I really have learned something along the way.”)

- In Anne Fadiman’s scheme, are you a “courtly” or a “carnal” reader? The former keeps a book pristine, while the latter has no qualms about cracking spines or dog-earing pages. (I’m a courtly reader, with the exception that I correct all errors in pencil.)

- Is a book a commercial product or a creative artifact? (“This is why authors quite often cross out the printed version of their name when they sign. Their action negates the book’s existence as a product of industry or commerce and reclaims it as the product of their own artistic effort.”)

- How is the experience of reading an e-book, or listening to an audiobook, different from reading a print book? (There is evidence that we remember less when we read on a screen, because we don’t have the physical cues of a book in our hand, plus “most people could in theory fit a lifetime’s reading on a single e-reader.”)

I would particularly recommend this to readers who have enjoyed Anne Fadiman’s Ex Libris, Alberto Manguel’s various books on libraries, and Tim Parks’s Where I’m Reading From.

A personal note: I was delighted to come across a mention of one of the visiting professors on my Master’s course in Victorian Literature at the University of Leeds, Matthew Rubery. In the autumn term of 2005, he taught one of my seminars, “The Reading Revolution in the Victorian Period,” which had a Book History slant and included topics like serial publication, anonymity and the rise of the media. A few years ago Rubery published an academic study of audiobooks, The Untold Story of the Talking Book, which Mole draws on for his discussion.

Two more favorite passages:

“when I’m reading, I’m not just spending time with a book, but investing time in cultivating a more learned version of myself.”

“A library is an argument. An argument about who’s in and who’s out, about what kinds of things belong together, about what’s more important and what’s less so. The books that we choose to keep, the ones that we display most prominently, and the ones that we shelve together make an implicit claim about what we value and how we perceive the world.”

My rating:

The Secret Life of Books will be published by Elliott & Thompson on Thursday 19th September. My thanks to Alison Menzies for arranging my free copy for review.

Reading Statistics for the First Half of 2019, Including Where My Books Came From

Almost halfway through the year: how am I doing on the reading goals I set for myself? So-so. I’m mostly managing one doorstopper and one classic per month, though sometimes I’ve had to fudge it a little with modern classics or a skim read. I’ve read precisely 0 travel classics, biographies, or re-reads, so those aims are a fail thus far. As to literature in translation, I’m doing better: it’s made up 8.1% of my reading, nearly double my 2018 percentage. And it looks like I’m on track to meet or exceed my Goodreads target.

The breakdown:

Fiction: 42.3%

Nonfiction: 42.3%

Poetry: 15.4%

(Exactly equal numbers of fiction and nonfiction books! What are the odds?!)

Male author: 41.3%

Female author: 56.7%

Non-binary author: 2%

(This is the first year when I’ve consciously read work by non-binary authors – three of them.)

E-books: 9.3%

Print books: 90.7%

(I seem to be moving further and further away from e-books now that they no longer make up the bulk of my paid reviewing.)

I always find it interesting to look back at where my books come from. Here are the statistics for the year so far, in both real numbers and percentages (not including books I’m currently reading, DNFs or books I only skimmed):

- Free print or e-copy from the publisher or author: 65 (43%)

- Public library: 31 (21%)

- Secondhand purchase: 21 (14%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley or Edelweiss: 12 (8%)

- Gifts: 9 (6%)

- Free, e.g. from Book Thing of Baltimore, local swap shop or free mall bookshop: 5 (3.5%)

- University library: 4 (2.5%)

- New book purchase: 2 (1.5%)

- Borrowed: 1 (0.5%)

How are you doing on any reading goals you set for yourself?

Where do you get most of your books from?

Final 2018 Statistics and Where My Books Came From

My most prolific year yet! (I’m sure I said the same last year, but really, this is a number I will most likely never top and shouldn’t attempt to.) People sometimes joke to me, “why not shoot for a book a day?!” but that’s not how I do things. Instead of reading one book from start to finish, I almost always have 10 to 20 books on the go at a time, and I tend to start and finish books in batches – I’m addicted to starting new books, but also to finishing them.

The breakdown:

Fiction: 44.9%

Nonfiction: 45.8%

Poetry: 9.3%

(I think this is the first time nonfiction has surpassed fiction! They’re awfully close, though. I read a bit less poetry this year than last.)

Male author: 38.1%

Female author: 61.9%

(Roughly the same thing has happened the last two years, which I find interesting because I have never consciously set out to read more books by women.)

E-books: 15.7%

Print books: 84.3%

(In 2016 I read one-third e-books; in 2017 it was one-quarter. For some reason I seem to find e-books less and less appealing. They are awfully useful for traveling. However, I’ve been cutting back on the reviewing gigs that rely on me reading only e-books.)

Works in translation: 4.8%

(Ouch – my reading in translation almost halved compared to last year. I’m going to have to make a point of reading more translated work next year.)

Where my books came from for the whole year:

- Free print or e-copy from publisher: 28.7%

- Public library: 20.8%

- Secondhand purchase: 20.6%

- Downloaded from NetGalley or Edelweiss: 14.9%

- Gifts: 5%

- Free (giveaways, GET Free Bookshop, Book Thing of Baltimore, etc.): 3.8%

- University library: 3.2%

- New purchase (usually at a bargain): 1.5%

- Kindle purchase: 0.9%

- Borrowed: 0.6%

Some interesting additional statistics courtesy of Goodreads:

How did 2018 turn out for you reading-wise?

Happy New Year!

Where My Books Came from in the First Half of 2018

I find it interesting to look back at where my books come from, and how this changes from year to year. So far this year, it seems like I’m reading fewer e-books and more from various libraries. I’m also doing a bit better about reading the secondhand books I already own, but – like last year – the largest proportion of my reading is still review copies of new books.

Here are the statistics for the year so far, in both real numbers and percentages (not including the books I’m currently reading, DNFs and books I only skimmed BUT including picture books, which I don’t count towards my yearly total):

- Free print or e-copy from the publisher or author: 45 (28%)

- Public library: 42 (26%)

- Secondhand purchase: 29 (18%)

- Downloaded from NetGalley or Edelweiss: 27 (17%)

- University library: 8 (5%)

- Gifts: 5 (3%)

- Twitter giveaway win: 3 (2%)

- New (bargain) book purchase: 1 (0.5%)

- Kindle purchase: 1 (0.5%)

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.)

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.) Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.) Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!)

Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!) Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan