A Bookshop of One’s Own by Jane Cholmeley (Blog Tour)

Silver Moon, one of the Charing Cross Road bookshops, was a London institution from 1984 until its closure in 2001. “Feminism and business are strange bedfellows,” Jane Cholmeley soon realised, and this book is her record of the challenges of combining the two. On the spectrum of personal to political, this is much more manifesto than memoir. She dispenses with her own story (vicar’s tomboy daughter, boarding school, observing racism on a year abroad in Virginia, secretarial and publishing jobs, meeting her partner) via a 10-page “Who Am I?” opening chapter. However, snippets of autobiography do enter into the book later on; in one of my favourite short chapters, “Coming Out,” Cholmeley recalls finally telling her mother that she was a lesbian after she and Sue had been together nearly a decade.

The mid-1980s context plays a major role: Thatcherite policies (Section 28 outlawing the “promotion of homosexuality”), negotiations with the Greater London Council, and trying to share the landscape with other feminist bookshops like Sisterwrite and Virago. Although there were some low-key rivalries and mean-spirited vandalism, a spirit of camaraderie generally prevailed. Cholmeley estimates that about 30% of the shop’s customers were men, but the focus here was always on women. The events programme featured talks by an amazing who’s-who of women authors, Cholmeley was part of the initial roundtable discussions in 1992 that launched the Orange Prize for Fiction (now the Women’s Prize), and the café was designated a members’ club so that it could legally be a women-only space.

I’ve always loved reading about what goes on behind the scenes in bookshops (The Diary of a Bookseller, Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop, The Sentence, The Education of Harriet Hatfield, The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap, and so on), and Cholmeley ably conveys the buzzing girl-power atmosphere of hers. There is a fun sense of humour, too: “Dyke and Doughnut” was a potential shop name, and a letter to one potential business partner read, “you already eat lentils, and ride a bicycle, so your standard of living hasn’t got much further to fall, we happen to like you an awful lot, and think we could all work together in relative harmony”.

However, the book does not have a narrative per se; the “A Day in the Life of… (1996)” chapter comes closest to what those hoping for a bookseller memoir might be expecting, in that it actually recreates scenes and dialogue. The rest is a thematic chronicle, complete with lists, sales figures, profitability charts, and excerpted documents, and I often got lost in the detail. The fact that this gives the comprehensive history of one establishment makes it a nostalgic yearbook that will appeal most to readers who have a head for business, were dedicated Silver Moon customers, and/or hold a particular personal or academic interest in the politics of the time and the development of the feminist and LGBT movements.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and Mudlark for the free copy for review.

Buy A Bookshop of One’s Own from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was happy to be part of the blog tour for the release of this book. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

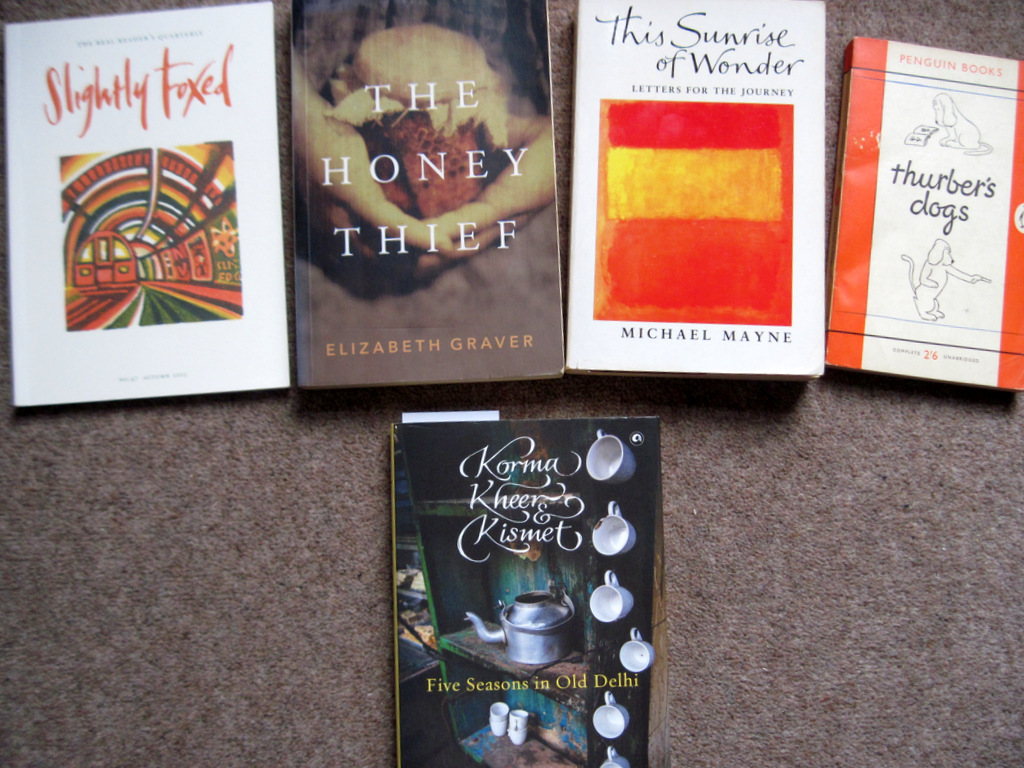

Happy Birthday & Bookshop Day

Happy Bookshop Day from Hay-on-Wye (and its newest bookshop, Gay on Wye)!

Today is my 40th birthday and I have been spending the weekend book shopping, reading, eating and drinking. What more could I ask for?

Before we left for Wales, I had my book club over for birthday cakes and bubbles. My husband made me a chocolate Guinness cake (vegan so everyone could share it) and pumpkin chai cupcakes; both recipes were from Hummingbird Bakery cookbooks.

I’ll report back on Monday with my book haul and trip highlights.

For now, here are some sweet lines from a children’s book I read this morning, about cats named Tom and Mot who discover that friendship and imagination are the greatest gifts, and that present has a double meaning: the now that must be appreciated.

“And then it was time for a hot drink and the cake. The cake tasted like the BEST birthday cake in the world. … ‘Today was the best present in the world,’ said Tom. ‘The perfect present!’”

A May Sarton Birthday Celebration

These days I consider May Sarton one of my favourite authors, but I’ve only been reading her for about nine years, since I picked up Journal of a Solitude on a whim. (Ten years prior, when I was a senior in college working in a used bookstore on evenings and weekends, a customer came up and asked me if we had anything by May Sarton. I had never heard of her so said no, only later discovering that we shelved her in with Classic literature. Huh. I can only apologize to that long-ago customer for my ignorance and negligence.)

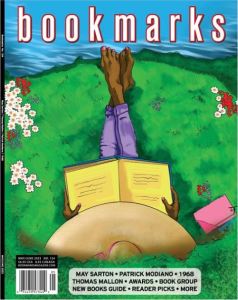

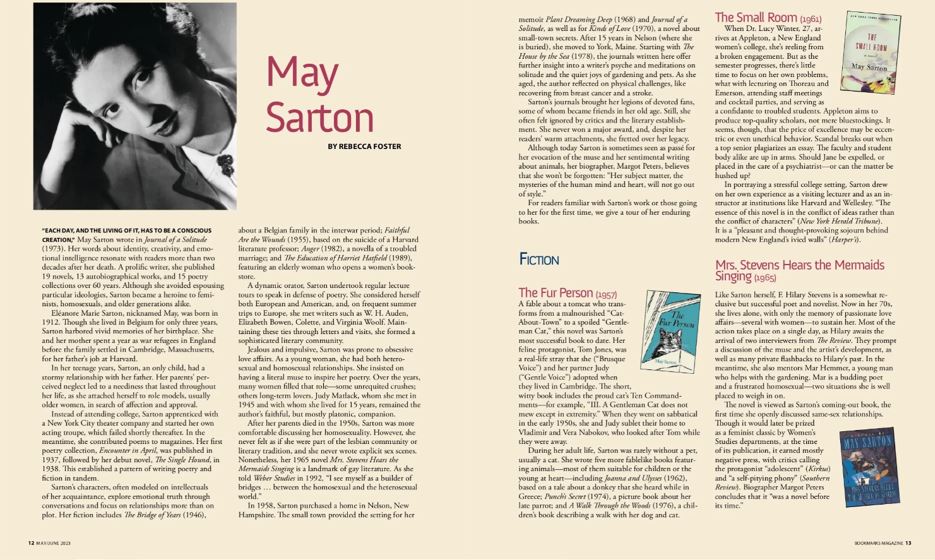

A general-interest article I wrote on May Sarton’s life and work appears in the May/June 2023 issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I am an associate editor. I submitted this feature back in August 2019, so it’s taken quite some time for it to see the light of day, but I’m pleased that the publication happened to coincide with the anniversary of her birth. In fact, today, May 3rd, would have been her 111th birthday. For the article, I covered a selection of Sarton’s fiction and nonfiction, and gave a brief discussion of her poetry (which the magazine doesn’t otherwise cover).

A general-interest article I wrote on May Sarton’s life and work appears in the May/June 2023 issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I am an associate editor. I submitted this feature back in August 2019, so it’s taken quite some time for it to see the light of day, but I’m pleased that the publication happened to coincide with the anniversary of her birth. In fact, today, May 3rd, would have been her 111th birthday. For the article, I covered a selection of Sarton’s fiction and nonfiction, and gave a brief discussion of her poetry (which the magazine doesn’t otherwise cover).

The two below, a journal and a novel, are works I’ve read more recently. Both were secondhand purchases, I think from Awesomebooks.com.

Encore: A Journal of the Eightieth Year (1993)

Sarton is one of those reasonably rare authors who published autobiography, fiction AND poetry. I know I’m not alone in thinking that the journals and memoirs are where she really shines. (She herself was proudest of her poetry, and resented the fact that publishers only seemed to be interested in novels because they were what sold.) I came to her through her journals, which she started writing in her sixties, and I love them for how frankly they come to terms with ageing and the ill health and loss it inevitably involves. They are also such good, gentle companions in that they celebrate seasonality and small joys: her beautiful New England homes, her gardening hobby, her pets, and her writing routines and correspondence.

Sarton is one of those reasonably rare authors who published autobiography, fiction AND poetry. I know I’m not alone in thinking that the journals and memoirs are where she really shines. (She herself was proudest of her poetry, and resented the fact that publishers only seemed to be interested in novels because they were what sold.) I came to her through her journals, which she started writing in her sixties, and I love them for how frankly they come to terms with ageing and the ill health and loss it inevitably involves. They are also such good, gentle companions in that they celebrate seasonality and small joys: her beautiful New England homes, her gardening hobby, her pets, and her writing routines and correspondence.

Encore was the only journal I had left unread; soon it will be time to start rereading my top few. When Sarton wrote this in 1991–2, she was recovering from a spell of illness and assumed it would be her final journal. (In fact, At Eighty-Two would appear two years later.) Although she still struggles with pain and low energy, the overall tone is of gratitude and rediscovery of wonder. Whereas a few of the later journals can get a bit miserable because she’s so anxious about her health and the state of the world, here there is more looking back at life’s highlights. Perhaps because Margot Peters was in the process of researching her biography (which would not appear until after her death), she was nudged into the past more often. I especially appreciated a late entry where she lists “peak experiences,” ranging from her teen years to age 80. What a positive way of thinking about one’s life!

For many months I kept this as a bedside book and read just an entry or two a night. When I started reading it more quickly and straight through, I did note some repetition, which Sarton worried would result from her dictating into a recording device. But I don’t think this detracts significantly. In this volume, events of note include a trip to London and commemorative publications plus a conference all to mark her 80th birthday. She’s just as pleased with tiny signs of her success, though, such as a fan letter saying The House by the Sea inspired the reader to put up a bird feeder. ![]()

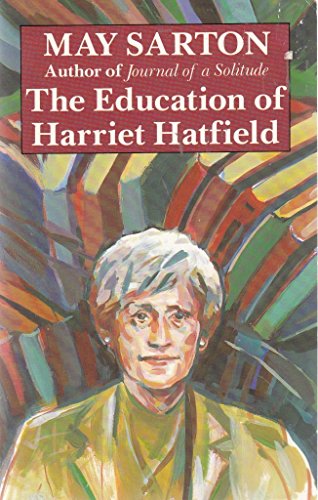

The Education of Harriet Hatfield (1988)

This is my eighth Sarton novel. In general, I’ve had less success with her fiction as it can be formulaic: characters exist to play stereotypical roles and/or serve as mouthpieces for the author’s opinions. That’s certainly true of Harriet Hatfield, who, like the protagonist of Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing, is fairly similar to Sarton. After the death of her long-time partner, Vicky, who ran a small publishing house, sixty-year-old Harriet decides to open a women’s bookstore in a Boston suburb. She has no business acumen, just enthusiasm (and money, via the inheritance from Vicky). College girls, housewives, nuns and older feminists all become regulars, but Hatfield House also attracts unwanted attention in this dodgy neighbourhood, especially after a newspaper outs Harriet: graffiti, petty theft and worse. The police are little help, but Harriet’s brothers and a local gay couple promise to look out for her.

The central struggle for Harriet is whether she will remain a private lesbian – as one customer says to her, “you are old and respectable and no one would ever guess”; that is, she can pass as straight – or become part of a more audible, visible movement toward equal rights. It’s cringe-worthy how unsubtly Sarton has Harriet recognize (the “Education” the title speaks of) her privilege and accept her parity with other minorities through friendships with a Black mother, a battered wife who gets an abortion, and a man whose partner is dying of AIDS. Harriet’s brother, too, comes out to her as gay, and I was uneasy with the portrayal of him and the AIDS patient as promiscuous to the point of bringing any suffering on themselves.

The central struggle for Harriet is whether she will remain a private lesbian – as one customer says to her, “you are old and respectable and no one would ever guess”; that is, she can pass as straight – or become part of a more audible, visible movement toward equal rights. It’s cringe-worthy how unsubtly Sarton has Harriet recognize (the “Education” the title speaks of) her privilege and accept her parity with other minorities through friendships with a Black mother, a battered wife who gets an abortion, and a man whose partner is dying of AIDS. Harriet’s brother, too, comes out to her as gay, and I was uneasy with the portrayal of him and the AIDS patient as promiscuous to the point of bringing any suffering on themselves.

Still, when I consider that Sarton was in her late seventies at the time she was writing this, and that public knowledge of AIDS would have been poor at best, I think this was admirably edgy. Harriet’s dilemma reflects Sarton’s own identity crisis, as expressed in Encore: “I do not wish to be labeled as a lesbian and do not wish to be labeled as a woman writer but consider myself a universal writer who is writing for human beings.” Nowadays, though, what Harriet deems discretion comes across as cowardice and priggishness.

While there are elements of Harriet Hatfield that have not aged well, if you focus on the Bythell-esque bookshop stuff (“I find that the people I love best are those who come in to browse, the silent shy ones, who are hungry for books rather than for conversation”) rather than the consciousness-raising or the mystery subplot, you might enjoy it as much as I did. Kudos for the first and last lines, anyway: “How rarely is it possible for anyone to begin a new life at sixty!” and “It’s the real world and I am fully alive in it.” ![]()

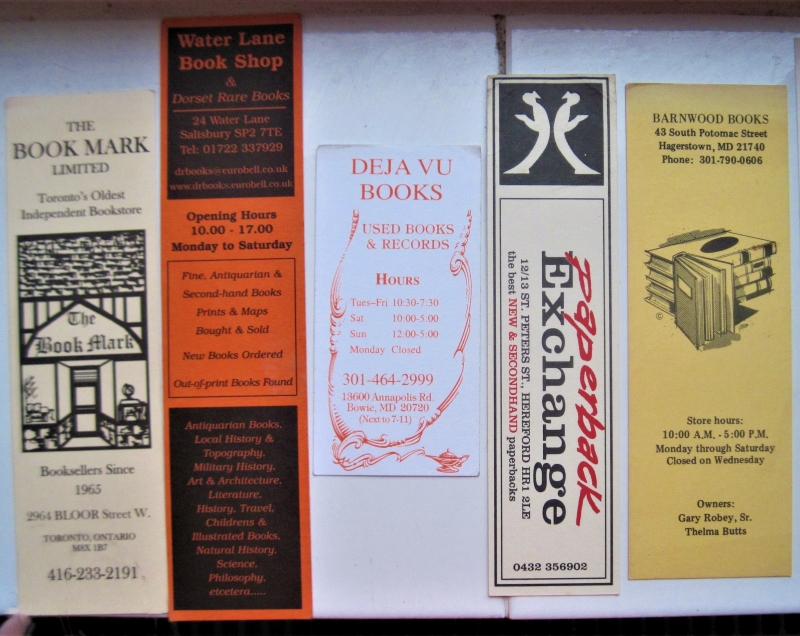

Sad Souvenirs: Defunct Bookshops’ Bookmarks

I’m a dedicated bookmark user and probably have at least 120–150 that I rotate through, matching marker to book subject matter or reading location whenever possible. A sorry subset of my collection commemorates bookshops (secondhand and/or new stock) that no longer exist. I was a customer at a couple of these, but only know of the others through bookmarks that I found at random, e.g. in secondhand purchases from other stores. Through Google Earth, I tracked down what you’ll find where these shops used to be.

Shops I visited:

Déjà Vu Books (Bowie, Maryland)

This was my local secondhand bookshop when I was a teenager. I would wheedle occasional visits out of my mother until my friends and I got our driving licenses and could go by ourselves. My friend Rachael and I would stop there after karate on a Saturday morning.

What I remember purchasing there: A near-complete set of Dickens’s works, blue/green cloth hardbacks, early 20th century, for $30; an Agatha Christie omnibus I gave to my mother.

What it is now: Chi Bella Natural Hair Boutique

Water Lane Book Shop (Salisbury, England)

My husband is a Hampshire lad. Salisbury was a relatively nearby town we would explore when I went to visit him while we were dating or engaged. An average daytrip would include touring the cathedral, having tea at the Polly Tearooms, and – in a waterside location just along from the cathedral square – having a nose through the well-stocked shelves of this compact shop.

What I remember purchasing there: Lots of my secondhand David Lodge paperbacks.

What it is now: A private residence (it had just sold as of Streetview in June 2018)

Others I only learned about through their orphan bookmarks:

Barnwood Books (Hagerstown, Maryland)

The bookmark looks old enough that I had to ask myself whether the shop might have been supplanted by Wonder Book & Video, a small chain I first discovered as a young teen. It has branches in Frederick (where I went to college; I worked there part-time in my senior year) and Hagerstown, and most recently opened in Gaithersburg. At the least, Wonder Book probably absorbed their stock when they closed.

What it is now: An empty storefront between a gastropub and a home fashions store (as of October 2019)

The Book Mark (Toronto, Canada)

I found this bookmark inside a secondhand book I bought from the Frederick Wonder Book & Video. I assumed the shop was still extant, but I checked in with Marcie (Buried in Print) and she sent me an article explaining that it was priced out of the neighbourhood and closed in 2012. It had been the oldest independent bookstore in Toronto. (This article gives more information.)

What it is now: Nails on Bloor, a nails and waxing parlour

Paperback Exchange (Hereford, England)

I can’t recall where I found this bookmark, but I wish a shop with this policy still existed! From the reverse: “The Paperback Exchange system: up to HALF the purchase price of books bought from us, against further purchases; up to a QUARTER on good quality paperbacks bought elsewhere.”

What it is now: On the June 2018 Streetview, it’s either the closed-down charity shop or the school uniform shop.

A nice postscript:

Royal Oak Bookshop (Front Royal, Virginia)

The bookmark I found in a used book looked so old I wasn’t sure if the shop would still exist. I was going to include it in the post as one of the defunct ones. But just to be sure, I decided to try hunting it down through the website…

Do you commemorate any deceased bookshops through their memorabilia?

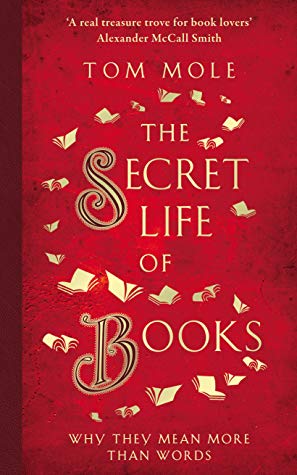

The Secret Life of Books by Tom Mole

If you’re like me and author Tom Mole, the first thing you do in any new acquaintance’s house is to scrutinize their bookshelves, whether openly or surreptitiously. You can learn all kinds of surprising things about what someone is interested in, and holds dear, from the books on display. (And if they don’t have any books around, should you really be friends?)

If you’re like me and author Tom Mole, the first thing you do in any new acquaintance’s house is to scrutinize their bookshelves, whether openly or surreptitiously. You can learn all kinds of surprising things about what someone is interested in, and holds dear, from the books on display. (And if they don’t have any books around, should you really be friends?)

Mole runs the Centre for the History of the Book at the University of Edinburgh, where he is a professor of English Literature and Book History. His specialist discipline and this book’s subtitle – “Why They Mean More than Words” – are clues that here he’s concerned with books more as physical and cultural objects than as containers of knowledge and stories:

“reading them is only one of the things we do with books, and not always the most significant. For a book to signal something about you, you don’t necessarily need to have read it.”

From the papyrus scroll to the early codex, from a leather-bound first edition to a mass-market paperback, and from the Kindle to the smartphone reading app, Mole asks how what we think of as a “book” has changed and what our different ways of accessing and possessing books say about us. He examines the book as a basis of personal identity and relationships with other people. His learned and digressive history of the book contains many pleasing pieces of trivia about authors, libraries and bookshops, making it a perfect gift for bibliophiles. I also enjoyed the three “interludes,” in which he explores three paintings that feature books.

There are a lot of talking points here for book lovers. Here are a few:

- Are you a true collector, or merely an “accumulator” of books? (Mole is the latter, as am I. “I have a few modest antiquarian volumes, but most of my books are paperbacks … I was the first in my immediate family to go to university, and I suspect the books on my shelves reassure me that I really have learned something along the way.”)

- In Anne Fadiman’s scheme, are you a “courtly” or a “carnal” reader? The former keeps a book pristine, while the latter has no qualms about cracking spines or dog-earing pages. (I’m a courtly reader, with the exception that I correct all errors in pencil.)

- Is a book a commercial product or a creative artifact? (“This is why authors quite often cross out the printed version of their name when they sign. Their action negates the book’s existence as a product of industry or commerce and reclaims it as the product of their own artistic effort.”)

- How is the experience of reading an e-book, or listening to an audiobook, different from reading a print book? (There is evidence that we remember less when we read on a screen, because we don’t have the physical cues of a book in our hand, plus “most people could in theory fit a lifetime’s reading on a single e-reader.”)

I would particularly recommend this to readers who have enjoyed Anne Fadiman’s Ex Libris, Alberto Manguel’s various books on libraries, and Tim Parks’s Where I’m Reading From.

A personal note: I was delighted to come across a mention of one of the visiting professors on my Master’s course in Victorian Literature at the University of Leeds, Matthew Rubery. In the autumn term of 2005, he taught one of my seminars, “The Reading Revolution in the Victorian Period,” which had a Book History slant and included topics like serial publication, anonymity and the rise of the media. A few years ago Rubery published an academic study of audiobooks, The Untold Story of the Talking Book, which Mole draws on for his discussion.

Two more favorite passages:

“when I’m reading, I’m not just spending time with a book, but investing time in cultivating a more learned version of myself.”

“A library is an argument. An argument about who’s in and who’s out, about what kinds of things belong together, about what’s more important and what’s less so. The books that we choose to keep, the ones that we display most prominently, and the ones that we shelve together make an implicit claim about what we value and how we perceive the world.”

My rating: ![]()

The Secret Life of Books will be published by Elliott & Thompson on Thursday 19th September. My thanks to Alison Menzies for arranging my free copy for review.

A Trip to Wigtown, Scotland’s Book Town

Wigtown is tucked away in the southwest corner of Scotland in Galloway, a region that doesn’t draw too many tourists. It did remind us a lot of Hay-on-Wye, the Book Town in Wales, what with the dry-stone walls, rolling green hills with more imposing mountains behind, sheep in the fields, and goodly number of bookshops. Wigtown is a sleepier place – it’s really just one main street and square – and has fewer bookshops and eateries overall, but the shops it does have are mainly large and inviting, and several are lovely bookshops-cum-cafés where you can pause for tea/coffee and cake before continuing with your book browsing. It rained for much of our trip and even snowed on a couple of brief occasions, but we got one day of very good weather and made the best of all the rest.

Day 1, Monday the 2nd: Six-plus hours of driving, partially in the sleet and snow, saw us arriving to our spacious and comfortable B&B by 6 p.m., giving us an hour to freshen up before dinner in the dining room. Cullen skink (leek and potato soup with chunks of smoked haddock); pork chops in a mustard cream sauce with roast parsnips, boiled potatoes and carrots, and mashed swede (aka rutabaga); and chocolate cake with gingerbread sauce. All delicious!

Day 2, Tuesday the 3rd: Smoked salmon and scrambled eggs for breakfast, accompanied by plenteous tea and toast. Off in the drizzle to see some local sites: Torhouse stone circle and Crook of Baldoon RSPB bird reserve. Nice sightings of whooper swans, pink-footed geese and lapwings, and a panoramic view of Wigtown across the way. Back to the car in the steady rain to find that we had a flat tire. Thanks to our foot pump, we got back to the W. Barclay garage in town, where they ordered a new tire and fitted the spare wheel. In the afternoon we drove to the Isle of Whithorn to see the 13th-century St. Ninian’s Chapel ruins and St. Ninian’s Cave. In the evening we went to Craft for beer/cider and the weekly acoustic music night, which, alas, just ended up being two old guys playing Americana songs on guitars.

Today’s book shopping: Glaisnock Café, where we also stopped for coffee and a tasty slice of courgette and avocado cake; The Open Book (run by Airbnb customers – this week it was Maureen from Pennsylvania and her niece Rebecca from Switzerland; they’d booked the experience two years ago, and the wait is now up to three years); the Wigtown Community shop (a charity shop); and browsing at Old Bank Books and Byre Books.

I loved seeing lots of Bookshop Band merchandise around. This was in the Festival Shop.

Day 3, Wednesday the 4th: Vegetarian ‘full Scottish’ cooked breakfast to fuel us for a rainy day of bookshops and explorations further afield. 12 p.m.: return trip to the garage to have our tire fitted. All the staff were so friendly and pleasant. They seemed delighted to see tourists around, and were interested in where we came from and what we were finding to do in the area. Mr. Barclay himself had one of the thickest Scottish accents I’ve ever heard, but I managed to decipher that he thinks of Galloway as “the next best place to heaven,” despite the weather. We spotted a local ‘celebrity’, Ben of the Bookshop Band, in the Co-op, but didn’t say hello as he was trying to pay for his shopping and had the baby in tow.

In the afternoon we ventured to Newton Stewart, the nearest big town, to buy petrol, picnic supper food, and another secondhand book at the community shop there. We retreated from the sudden snow for a scrumptious dinner of smoked salmon, black pudding and haggis (all of them battered and fried, with chips!) at a diner-like smokehouse. Back in Wigtown, we got a mainly dry evening to do the Martyrs’ Walk. In 1685 two Covenanters (Scottish reformers who broke from Charles I’s Anglican Church), Margaret McLachlan, 63, and Margaret Wilson, 18, were tied to stakes on the mud flats and allowed to drown in the rising tide.

Today’s book shopping: THE BOOKSHOP. I’ve meant to visit ever since I read Jessica Fox’s memoir, Three Things You Need to Know about Rockets, in February 2013. Previously based in California, Fox decided on a whim to visit a bookshop in Scotland and ended up here at the country’s largest. She promptly fell in love with the bookshop owner and with Wigtown itself; though she and Shaun Bythell are no longer an item, she has been a major mover and shaker in the town, playing a role in the annual festival and establishing The Open Book.

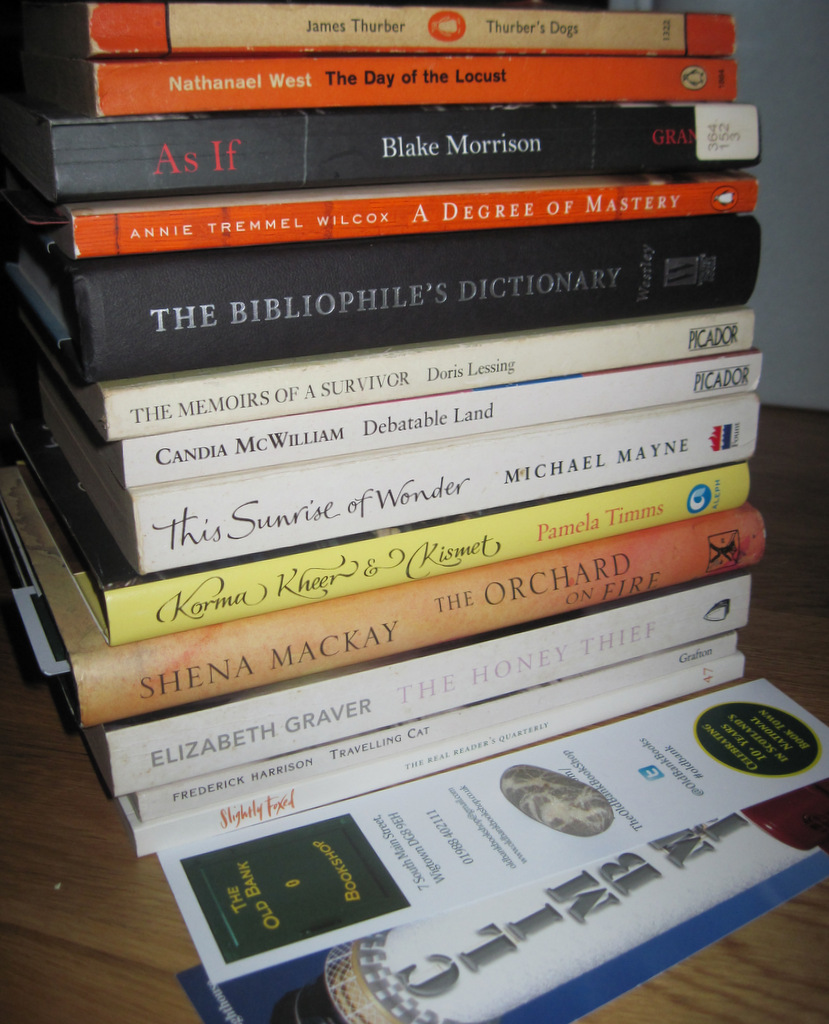

The Bookshop is a wonderfully rambling place with lots of nooks and crannies housing all sorts of categories. Look out for the shot and mounted Kindle, the Festival bed, the stuffed badger, a scroll of bookseller’s rules, Captain the cat, and a display of Bythell’s The Diary of a Bookseller. Together we found £35 worth of books we wanted to buy – whew! – thanks to my husband’s niche nature books, and had a nice chat with the man himself at the till. He signed my book, commiserated with us about the weather and our trip to see “Willie” (Barclay), and gave us tips for what to see locally. You’d hardly believe he’s the same curmudgeon who wrote the book. Now that I’ve been to the town and the shop, it’s time for me to start rereading it.

We also perused the smallish but very nice selection at Beltie Books, where we made a welcome stop for a cappuccino and some cookies, and I bought a cut-price new book at the Festival Shop. (They stock books by festival speakers plus a curated selection of new releases.)

Day 4, Thursday the 5th: SUNSHINE, at last! After hearty omelettes, we headed to the hill that overlooks the town to get the best views of the week. On to Monreith for a charming coastal walk up to the Gavin Maxwell monument of a bronze otter. (He wrote Ring of Bright Water, which my husband brought along to read on our trip.) After a lunch stop back in town, it was out to the red kite feeding station about 40 minutes away – I came for the books; my husband came for the red kites. Though they’re common enough in our part of Berkshire, he was keen to see the site of another recent reintroduction. Wales also has a feeding station we visited some years ago, and on both occasions seeing dozens of birds swoop down for meat was quite the spectacle – though here you sit on an open porch, even closer to the action. We did a few other short walks in the area, finishing off with a sunset sit in Wigtown’s bird hide.

Today’s book shopping: ReadingLasses calls itself Britain’s only women’s bookshop. They stock Persephone Books direct from Bloomsbury, and they also have a large selection of secondhand books. This is the best place to go in town for a light meal and a snack. We had delicious homemade soup with soda bread for an early lunch, followed by coffee and tiffin. I bought a novel by Candia McWilliam, a Scottish author I’ve only read nonfiction by before.

At Curly Tale Books, the children’s bookshop next-door to The Bookshop, we bought a picture book about the local ‘belted’ Galloway cows for our niece. We didn’t realize the shop owner is also the author! She offered to sign the book for us, but we decided that a five-year-old wouldn’t appreciate it enough.

Day 5, Friday the 6th: Full Scottish breakfast to see us on our way, and a farewell to the two B&B cats, including the fluffiest cat on earth. To break up the rather arduous journey, we stopped early on at the Cairn Holy stone circle/tomb and the Cream o’ Galloway farm shop for cheese and ice cream. Home at 7:30 p.m. to find something from the freezer for dinner, unpack and shelve all these new books.

Cairn Holy

Total acquisitions: 13 books for me, 7 books for my husband, 3 books for gifts

Wigtown is more than twice as far away as Hay is for us, so we’re less likely to go back. (It’s also a tough place to find a decent evening meal.) However, I’d like to think that life will take me back to Wigtown someday, perhaps for the Festival, or for a stay at The Open Book – though I’d have to start planning ahead to 2021!

What I read:

Bits of lots of books I had on the go, but mostly a few vaguely appropriate titles:

Under the Skin by Michel Faber was the perfect book for reading on rainy Scottish highways. I’m so glad I decided at the last minute to bring it. Isserley drives along Highland roads picking up hitchhikers – but only the hunky males – to take back to her farm near the Moray Firth. It’s likely that you already know the setup of this even if you haven’t read it, perhaps from the buzz around the 2013 film version starring Scarlett Johansson. It must have been so difficult for the first reviewers and interviewers to discuss the book without spoilers back in 2000. David Mitchell, in his introduction to my Canons series reprint, does an admirable job of suggesting the eeriness of the contents without giving anything significant away.

Shelve this under science fiction, though it veers towards horror and then becomes a telling allegory. I knew the basic plot beforehand, but there were still some surprises awaiting me, and I was impressed with how Faber pulled it all off. Keep an eye open for how he uses the word “human.” This has a lot to say about compassion and dignity, and how despite our differences we are fundamentally the same “under the skin.” ![]()

An atmospheric line: “The fields all around her house were shrouded in snow, with patches of dark earth poking through here and there as if the world were a rich fruit cake under cream.”

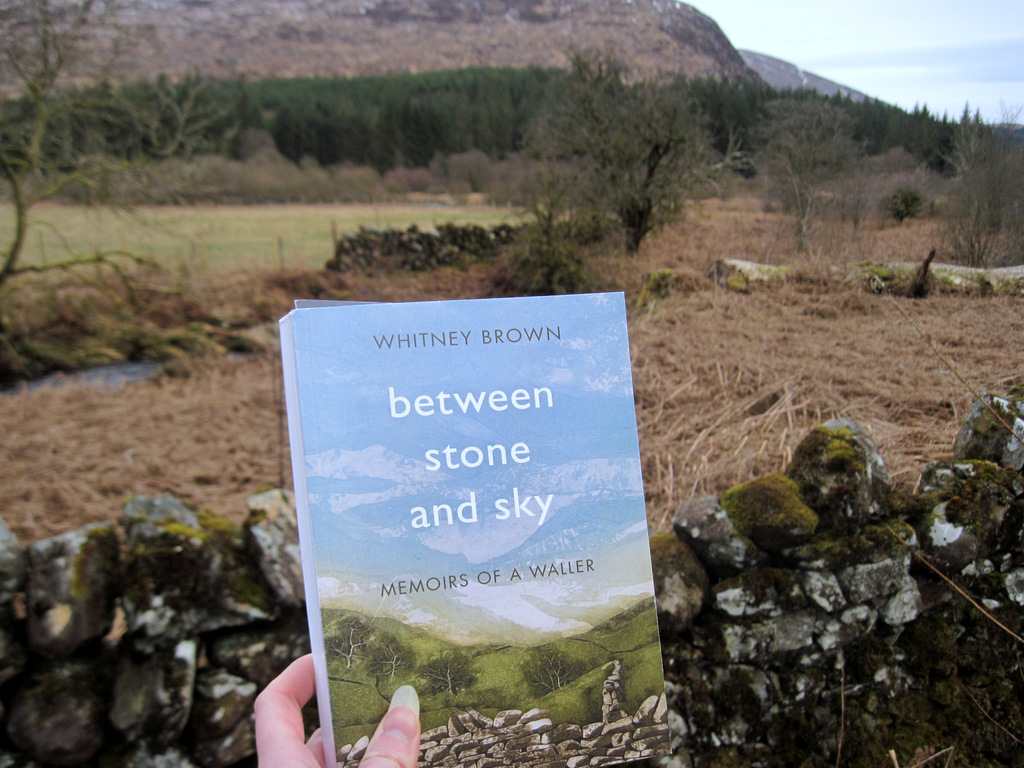

Between Stone and Sky: Memoirs of a Waller by Whitney Brown: For a TLS review. Brown, from South Carolina, trained as a dry-stone waller in Wales (where she fell in love with a man who wouldn’t marry her), but we saw plenty such walls in Scotland too. As an expat I could relate to her feeling of being split between two countries. ![]() (Releases May 17th.)

(Releases May 17th.)

I n the Days of Rain: A daughter. A father. A cult. by Rebecca Stott: I read the first two-fifths or so, mostly in the car and over our leisurely B&B breakfasts. One branch of Stott’s Exclusive Brethren family came from Eyemouth, a Scottish fishing village. A family memoir, a bereavement memoir, a theological theme: this brings together a lot of my favorite things. And it won last year’s Costa Biography Award, so you know it’s got to be good.

n the Days of Rain: A daughter. A father. A cult. by Rebecca Stott: I read the first two-fifths or so, mostly in the car and over our leisurely B&B breakfasts. One branch of Stott’s Exclusive Brethren family came from Eyemouth, a Scottish fishing village. A family memoir, a bereavement memoir, a theological theme: this brings together a lot of my favorite things. And it won last year’s Costa Biography Award, so you know it’s got to be good.

I also started two books by Scottish novelists, The Orchard on Fire by Shena Mackay and The Accidental by Ali Smith – though I don’t know if I’ll make it through the latter.

Daniel Clowes is a respected American graphic novelist best known for Ghost World, which was adapted into a 2001 film starring Scarlett Johansson. I’m not sure what I was expecting of Monica. Perhaps something closer to a quiet life story like

Daniel Clowes is a respected American graphic novelist best known for Ghost World, which was adapted into a 2001 film starring Scarlett Johansson. I’m not sure what I was expecting of Monica. Perhaps something closer to a quiet life story like  Ince is not just a speaker at the bookshops but, invariably, a customer – as well as at just about every charity shop in a town. Even when he knows he’ll be carrying his purchases home in his luggage on the train, he can’t resist a browse. And while his shopping basket would look wildly different to mine (his go-to sections are science and philosophy, the occult, 1960s pop and alternative culture; alongside a wide but utterly unpredictable range of classic and contemporary fiction and antiquarian finds), I sensed a kindred spirit in so many lines:

Ince is not just a speaker at the bookshops but, invariably, a customer – as well as at just about every charity shop in a town. Even when he knows he’ll be carrying his purchases home in his luggage on the train, he can’t resist a browse. And while his shopping basket would look wildly different to mine (his go-to sections are science and philosophy, the occult, 1960s pop and alternative culture; alongside a wide but utterly unpredictable range of classic and contemporary fiction and antiquarian finds), I sensed a kindred spirit in so many lines:

I read this over a chilled-out coffee at the Globe bar in Hay-on-Wye (how perfect, then, to come across the lines “I know the secret of life / Is to read good books”). Weatherhead mostly charts the rhythms of everyday existence in pandemic-era New York City, especially through a haiku sequence (“The blind cat asleep / On my lap—and coffee / Just out of reach” – a situation familiar to any cat owner). His style is matter-of-fact and casually funny, juxtaposing random observations about hipster-ish experiences. From “Things the Photoshop Instructor Said and Did”: “Someone gasped when he increased the contrast / I feel like everyone here is named Taylor.”

I read this over a chilled-out coffee at the Globe bar in Hay-on-Wye (how perfect, then, to come across the lines “I know the secret of life / Is to read good books”). Weatherhead mostly charts the rhythms of everyday existence in pandemic-era New York City, especially through a haiku sequence (“The blind cat asleep / On my lap—and coffee / Just out of reach” – a situation familiar to any cat owner). His style is matter-of-fact and casually funny, juxtaposing random observations about hipster-ish experiences. From “Things the Photoshop Instructor Said and Did”: “Someone gasped when he increased the contrast / I feel like everyone here is named Taylor.”

Tookie, the narrator, has a tough exterior but a tender heart. When she spent 10 years in prison for a misunderstanding-cum-body snatching, books helped her survive, starting with the dictionary. Once she got out, she translated her love of words into work as a bookseller at

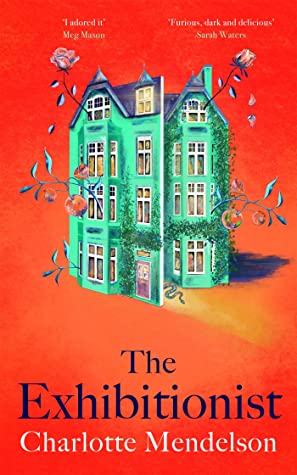

Tookie, the narrator, has a tough exterior but a tender heart. When she spent 10 years in prison for a misunderstanding-cum-body snatching, books helped her survive, starting with the dictionary. Once she got out, she translated her love of words into work as a bookseller at  Artists, dysfunctional families, and limited settings (here, one crumbling London house and its environs; and about two days across one weekend) are irresistible elements for me, and I don’t mind a work being peopled with mostly unlikable characters. That’s just as well, because the narrative orbits Ray Hanrahan, a monstrous narcissist who insists that his family put his painting career above all else. His wife, Lucia, is a sculptor who has always sacrificed her own art to ensure Ray’s success. But now Lucia, having survived breast cancer, has the chance to focus on herself. She’s tolerated his extramarital dalliances all along; why not see where her crush on MP Priya Menon leads? What with fresh love and the offer of her own exhibition in Venice, maybe she truly can start over in her fifties.

Artists, dysfunctional families, and limited settings (here, one crumbling London house and its environs; and about two days across one weekend) are irresistible elements for me, and I don’t mind a work being peopled with mostly unlikable characters. That’s just as well, because the narrative orbits Ray Hanrahan, a monstrous narcissist who insists that his family put his painting career above all else. His wife, Lucia, is a sculptor who has always sacrificed her own art to ensure Ray’s success. But now Lucia, having survived breast cancer, has the chance to focus on herself. She’s tolerated his extramarital dalliances all along; why not see where her crush on MP Priya Menon leads? What with fresh love and the offer of her own exhibition in Venice, maybe she truly can start over in her fifties. What I actually found, having limped through it off and on for seven months, was something of a disappointment. A frank depiction of the mental health struggles of the Oh family? Great. A paean to how books and libraries can save us by showing us a way out of our own heads? A-OK. The problem is with the twee way that The Book narrates Benny’s story and engages him in a conversation about fate versus choice.

What I actually found, having limped through it off and on for seven months, was something of a disappointment. A frank depiction of the mental health struggles of the Oh family? Great. A paean to how books and libraries can save us by showing us a way out of our own heads? A-OK. The problem is with the twee way that The Book narrates Benny’s story and engages him in a conversation about fate versus choice. We’re back from our weekend in Bristol and Exeter to hang out with university friends and attend our goddaughter’s dedication service. On the way (ish) down, we stopped at Bookbarn International, one of my favorite places to look for secondhand books. The shop is always coming up with new ideas and ventures – a rare books room, a café, stationery and store-brand merchandise, new stock alongside the used books, and so on – and has recently been doing some renovating of the main shop space. I contributed to a crowdfunder for this and got to pick up my rewards while I was there, including the items at right and a £10 store voucher, which, along with the small balance of my vendor account, more than covered my purchases that day.

We’re back from our weekend in Bristol and Exeter to hang out with university friends and attend our goddaughter’s dedication service. On the way (ish) down, we stopped at Bookbarn International, one of my favorite places to look for secondhand books. The shop is always coming up with new ideas and ventures – a rare books room, a café, stationery and store-brand merchandise, new stock alongside the used books, and so on – and has recently been doing some renovating of the main shop space. I contributed to a crowdfunder for this and got to pick up my rewards while I was there, including the items at right and a £10 store voucher, which, along with the small balance of my vendor account, more than covered my purchases that day.