Recent Poetry Releases by Anderson, Godden, Gomez, Goodan, Lewis & O’Malley

Nature, social engagement, and/or women’s stories are linking themes across these poetry collections, much as they vary in their particulars. After my brief thoughts, I offer one sample poem from each book.

And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound by Morag Anderson

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

With thanks to Fly on the Wall Press for the free copy for review.

With Love, Grief and Fury by Salena Godden

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

… and while volunteering as an election teller at a polling station last week. It contains 81 poems (many of them overlong prose ones), making for a much lengthier collection than I would usually pick up. The repetition, wordplay and run-on sentences are really meant more for performance than for reading on the page, but if you’re a fan of Hollie McNish or Kae Tempest, you’re likely to enjoy this, too.

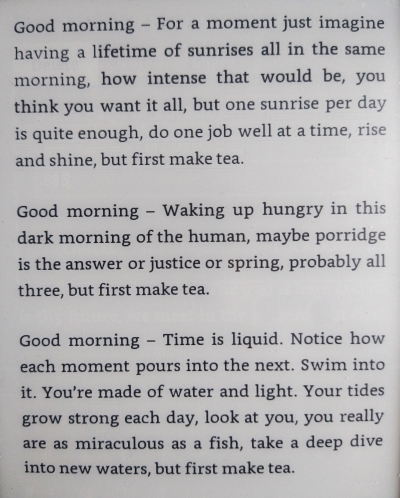

An excerpt from “But First Make Tea”

(Read via NetGalley) Published in the UK by Canongate Press.

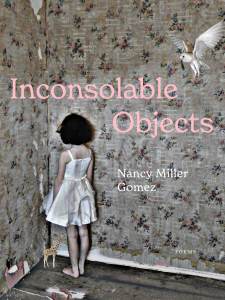

Inconsolable Objects by Nancy Miller Gomez

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

With thanks to publicist Sarah Cassavant (Nectar Literary) and YesYes Books for the e-copy for review.

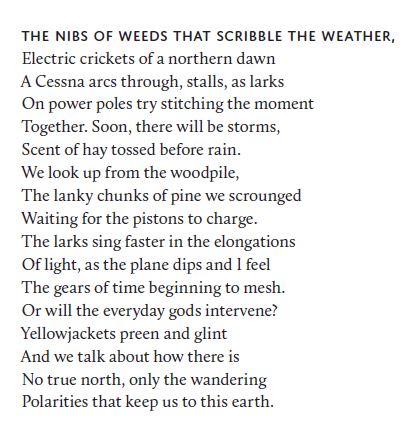

In the Days that Followed by Kevin Goodan

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

With thanks to Alice James Books for the e-copy for review.

From Base Materials by Jenny Lewis

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

“On Translation”

The trouble with translating, for me, is that

when I’ve finished, my own words won’t come;

like unloved step-children in a second marriage,

they hang back at table, knowing their place.

While their favoured siblings hold forth, take

centre stage, mine remain faint, out of ear-shot

like Miranda on her island shore before the boats

came near enough, signalling a lost language;

and always the boom of another surf – pounding,

subterranean, masculine, urgent – makes my words

dither and flit, become little and scattered

like flickering shoals caught up in the slipstream

of a whale, small as sand crabs at the bottom of a bucket,

harmless; transparent as zooplankton.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

The Shark Nursery by Mary O’Malley

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

“Holy”

The days lengthen, the sky quickens.

Something invisible flows in the sticks

and they blossom. We learn to let this

be enough. It isn’t; it’s enough to go on.

Then a lull and a clip on my phone

of a small girl playing with a tennis ball

her three-year-old face a chalice brimming

with life, and I promise when all this is over

I will remember what is holy. I will say

the word without shame, and ask if God

was his own fable to help us bear absence,

the cold space at the heart of the atom.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

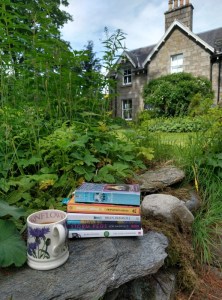

What Lies Hidden: Secrets of the Sea House & Night Waking

When I read Kay’s review of Sarah Maine’s The House Between Tides, the book seemed so familiar I did a double take. A Scottish island in the Outer Hebrides … dual contemporary and historical story lines … the discovery of a skeleton. It sounded just like Night Waking by Sarah Moss (another Sarah M.!), which I was already planning on rereading on our trip to the Outer Hebrides. Kay then suggested a readalike that ended up being even more similar, Elisabeth Gifford’s The Sea House (U.S. title), one of whose plots was Victorian and the skeleton in which was a baby’s. I passed on the Maine but couldn’t resist finding a copy of the Gifford from the library so I could compare it with the Moss. Both:

Secrets of the Sea House by Elisabeth Gifford (2013)

Although nearly 130 years separate the two protagonists, they are linked by the specific setting – a manse on the island of Harris – and a belief that they are descended from selkies. In 1992, Ruth and her husband are converting the Sea House into a B&B and hoping to start a family. When they find the remains of a baby with skeletal deformities reminiscent of a mermaid under the floorboards, Ruth plunges into a search for the truth of what happened in their home. In 1860, Reverend Alexander Ferguson lived here and indulged his amateur naturalist curiosity about cetaceans and the dubious creatures announced as “mermaids” (often poor taxidermy crosses between a monkey and a fish, as in The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock).

Although nearly 130 years separate the two protagonists, they are linked by the specific setting – a manse on the island of Harris – and a belief that they are descended from selkies. In 1992, Ruth and her husband are converting the Sea House into a B&B and hoping to start a family. When they find the remains of a baby with skeletal deformities reminiscent of a mermaid under the floorboards, Ruth plunges into a search for the truth of what happened in their home. In 1860, Reverend Alexander Ferguson lived here and indulged his amateur naturalist curiosity about cetaceans and the dubious creatures announced as “mermaids” (often poor taxidermy crosses between a monkey and a fish, as in The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock).

Ruth and Alexander trade off as narrators, but we get a more rounded view of mid-19th-century life through additional chapters voiced by the reverend’s feisty maid, Moira, a Gaelic speaker whose backstory reveals the cruelty of the Clearances – she won’t forgive the laird for what happened to her family. Gifford’s rendering of period prose wasn’t altogether convincing and there are some melodramatic moments: this could be categorized under romance, and I was surprised by the focus on Ruth’s traumatic upbringing in a children’s home after her mother’s death by drowning. Still, this was an absorbing novel and I actually learned a lot, including the currently accepted explanation for where selkie myths come from.

I also was relieved that Gifford uses real place names instead of disguising them (as Bella Pollen and Sarah Moss did). We passed through the tiny town of Scarista, where the manse is meant to be, on our drive. If I’d known ahead of time that it was a real place, I would have been sure to stop for a photo op (it must be this B&B!). We also stopped in Tarbert, a frequent point of reference, to visit the Harris Gin distillery. (Public library)

Night Waking by Sarah Moss (2011)

This was my first of Moss’s books and I have always felt guilty that I didn’t appreciate it more. I found the voice more enjoyable this time, but was still frustrated by a couple of things. Dr Anna Bennet is a harried mum of two and an Oxford research fellow trying to finish her book (on Romantic visions of childhood versus the reality of residential institutions – a further link to the Gifford) while spending a summer with her family on the remote island of Colsay, which is similar to St. Kilda. Her husband, Giles Cassingham, inherited the island but is also there to monitor the puffin numbers and track the effects of climate change. Anna finds a baby’s skeleton in the garden while trying to plant some fruit trees. From now on, she’ll snatch every spare moment (and trace of Internet connection) away from her sons Raph and Moth – and the builders and the police – to write her book and research what might have happened on Colsay.

Each chapter opens with an epigraph from a classic work on childhood (e.g. by John Bowlby or Anna Freud). Anna also inserts excerpts from her manuscript in progress and fragments of texts she reads online. Adding to the epistolary setup is a series of letters dated 1878: May Moberley reports to her sister Allie and others on the conditions on Colsay, where she arrives to act as a nurse and address the island’s alarming infant mortality statistics. It took me the entire book to realize that Allie and May are the sisters from Moss’s 2014 novel Bodies of Light; I’m glad I didn’t remember, as there was a shock awaiting me.

Each chapter opens with an epigraph from a classic work on childhood (e.g. by John Bowlby or Anna Freud). Anna also inserts excerpts from her manuscript in progress and fragments of texts she reads online. Adding to the epistolary setup is a series of letters dated 1878: May Moberley reports to her sister Allie and others on the conditions on Colsay, where she arrives to act as a nurse and address the island’s alarming infant mortality statistics. It took me the entire book to realize that Allie and May are the sisters from Moss’s 2014 novel Bodies of Light; I’m glad I didn’t remember, as there was a shock awaiting me.

According to Goodreads, I first read this over just four days in early 2012. (This was back in the days where I read only one book at a time, or at most two, one fiction and one nonfiction.) I remember feeling like I should have enjoyed its combination of topics – puffin fieldwork, a small island, historical research – much more, but I was irked by the constant intrusions of the precocious children. That is, of course, the point: they interrupt Anna’s life, sleep and research, and she longs for a ‘room of her own’ where she can be a person of intellect again instead of wiping bottoms and assembling sometimes disgusting meals. She loves her children, but hates the daily drudgery of motherhood. Thankfully, there’s hope at the end that she’ll get what she desires.

I had completely forgotten the subplot about the first family they rent out the new holiday cottage to (yet another tie-in to the Gifford, in which they’re preparing to open a guest house): a hot mess of alcoholic mother, workaholic father, and university-age daughter with an eating disorder. Zoe’s interactions with the boys, and Anna’s role as makeshift counsellor to her, are sweet, but honestly? I would have cut this story line entirely. Really, I longed for the novella length and precision of a later work like Ghost Wall. Still, I was happy to reread this, with Anna’s wry wit a particular highlight, and to discover for the first time (silly me!) that thread of connection with Bodies of Light / Signs for Lost Children. (Free from a neighbour)

Original rating:

My rating now:

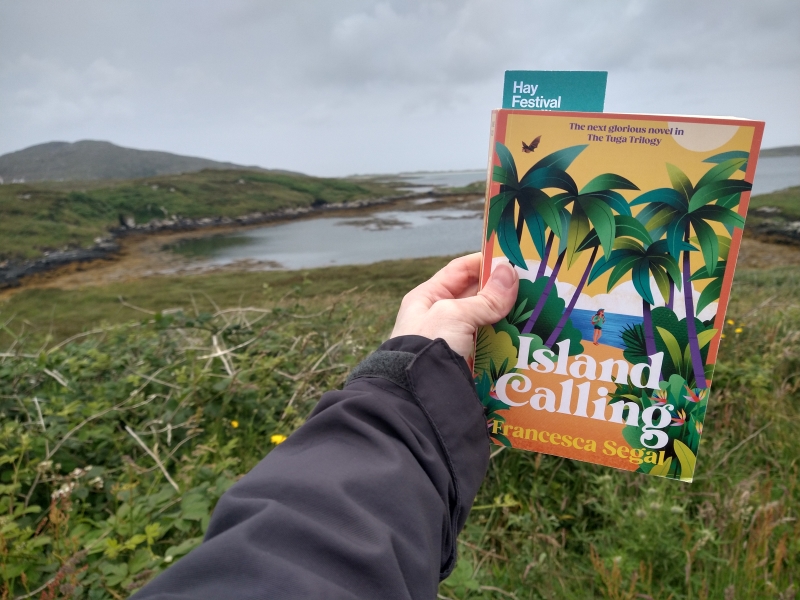

I enjoyed the Gifford enough to immediately request the library’s copy of one of her newer novels, The Lost Lights of St. Kilda, so my connection to the Western Isles can at least continue through my reading. I also found a pair of children’s novels plus a mystery novel set on St. Kilda, and I was sent an upcoming novel set on an island off the west coast of Scotland, so I’ll be on this Scotland reading kick for a while!

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

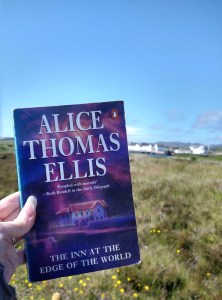

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)  1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)

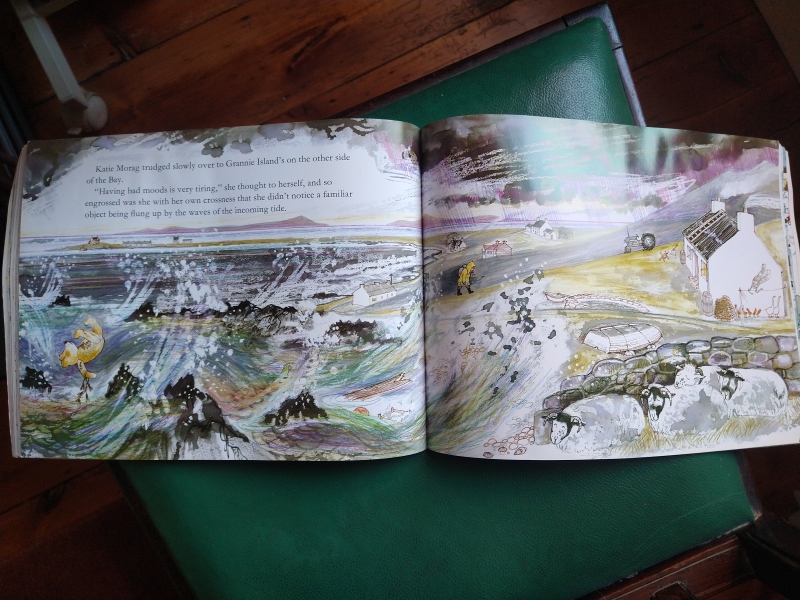

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)  I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)