Tag Archives: Haiti

20 Books of Summer, 10: Babel by R. F. Kuang (2022)

I substituted this in as my one doorstopper of the challenge after I failed with the new Persaud. It’s a bit of a cheat in that I actually started reading Babel in January, but I only just finished it this morning. I raced through the first 200 pages or so at the start of the year and loved all the geeky etymological footnotes and musings on translation. I thought I’d read it within a matter of days, which would have been a real feat for me. It’s hard to say why, instead, I stalled and found it difficult to regain sustained interest in the months that followed. Initially, it was a buddy read for me and my husband (his bookmark is still stranded at p. 178). His pithy comment, early on, was, “So, this is basically a woke Harry Potter?” And that’s actually a pretty apt summary. Four students at a magical academy – the Royal Institute of Translation at Oxford University, also known as Babel – find themselves questioning their responsibilities and loyalties as they confront the forces of evil, specifically colonialism.

When Robin Swift’s mother dies of cholera, he’s rescued from Canton by Professor Lovell and taken to England to train for entrance into Babel, a tower beside the Radcliffe Camera. He, Ramy (Indian), Victoire (Haitian) and Letty, the only white member of the quartet, are soon inseparable. While Victoire and Letty face prejudice for being female, it’s nothing to the experience of being racially other. Luckily, Babel values foreignness: intimate knowledge of other languages is an asset. In Kuang’s speculative 1830s setting, Britain’s economy is founded on a warped alchemy: silver is turned into energy to keep everyday life running smoothly in the industrializing nation. This is accomplished by harnessing the power of words. Silver bars are engraved with match-pairs – a phrase in a foreign language and its closest English counterpart – and the incantation of that untranslatable meaning sparks action. Spells keep bridges standing and traffic flowing; used for ill, they kill and destroy.

Robin and his friends gradually realise that their work at Babel is reinforcing mass poverty and the colonial system and, ultimately, fuelling future wars. “Truly, the only ones who seemed to profit from the silver industrial revolution were those who were already rich, and the select few others, who were cunning or lucky enough to make themselves so.” He becomes radicalized via the clandestine Hermes Society, which, Robin Hood-like, siphons silver resources away from where they are concentrated in Oxford to where they can help the oppressed. Surprised to learn who else is involved in Hermes, Robin (name not coincidental!) starts working behind the backs of his friends and professors, driven by conscience yet loath to give up the prospects he has through the tremendous privilege of being part of Babel. It goes from being an ivory tower of academia to being a hideaway for strikers and the besieged. And if you know your Bible stories, you’ll remember that Babel is destined to fall.

In faux-archaic fashion, Kuang has given her novel a lengthy subtitle: “Or: The Necessity of Violence – An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution.” The principle behind Hermes is that justice will never be achieved by negotiation; only by force. “Violence was the only thing that brought the colonizer to the table; violence was the only option.” Kuang published this fourth novel at age 26 and it manifests a certain youthful idealism. The sense of retrospective righteous anger is justified but also unsubtle; I felt similarly about Kuang’s Yellowface. Although there are exciting twists in the latter half of the book, I preferred the early semi-Dickensian atmosphere as Robin investigates his parentage and learns the joy of language and friendship. Kuang also adds a queer angle: an unrequited heterosexual crush comes to nothing because two same-sex friends are in love, even if they can never say. For as full-on and high-stakes as the plot becomes, I wished I could stay in this quieter mode.

Kuang has rendered the historical setting admirably and, though this is a typical adventure novel in that she has prioritized action over depth of characterization, one does get invested in the central characters and their interactions. The whole silver-working motif at first seems implausible but quickly becomes an accepted part of the background. Longstanding fantasy readers will probably have no problem reading this, but if you’re unsure and daunted by the 540-page length, ask yourself just how interested you are in word meanings and the history of colonialism and uprisings. (Little Free Library) ![]()

[P.S. OMG, have you seen her wedding photos from a few weeks ago?!]

Also two DNFs, argh!

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury)

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury)

Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)

Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)

20 Books of Summer, #19–20: Heat & The Gospel of Trees

Finishing off my summer reading project with a stellar biography-cum-travel book about Italian cuisine and a family memoir about missionary work in Haiti in the 1980s.

Heat by Bill Buford (2006)

(20 Books of Summer, #19) The long subtitle gives you an outline of the contents: “An Amateur’s Adventures as Kitchen Slave, Line Cook, Pasta-Maker, and Apprentice to a Dante-Quoting Butcher in Tuscany.” If Buford’s name sounds familiar, it’s because he was the founding editor of Granta magazine and publisher at Granta Books, but by the time he wrote this he was a staff writer for the New Yorker.

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

In between behind-the-scenes looks at frantic or dull sessions of food prep (“after you’ve made a couple thousand or so of these little ears [orecchiette pasta], your mind wanders. You think about anything, everything, whatever, nothing”), Buford traces Batali’s culinary pedigree through Italy and London, where Batali learned from the first modern celebrity chef, Marco Pierre White, and gives pen portraits of the rest of the kitchen staff. At first only trusted with chopping herbs, the author develops his skills enough that he’s allowed to work the pasta and grill stations, and to make polenta for 200 for a benefit dinner in Nashville.

Later, Buford spends stretches of several months in Italy as an apprentice to a pasta-maker and a Tuscan butcher. His obsession with Italian cuisine is such that he has to know precisely when egg started to replace water in pasta dough in historical cookbooks, and is distressed when the workers at the pasta museum in Rome can’t give him a definitive answer. All the same, the author never takes himself too seriously: he knows it’s ridiculous for a clumsy, unfit man in his mid-forties to be entertaining dreams of working in a restaurant for real, and he gives self-deprecating accounts of his mishaps in the various kitchens he toils in:

to stir the polenta, I was beginning to feel I had to be in the polenta. Would I finish cooking it before I was enveloped by it and became the darkly sauced meaty thing it was served with?

Compared to Kitchen Confidential, I found this less brash and more polished. You still get the sense of macho posturing from a lot of the figures profiled, but of course this author is not going to be in a position to interrogate food culture’s overweening masculinity. However, he does take a stand in support of small-scale food production:

Small food: by hand and therefore precious, hard to find. Big food: from a factory and therefore cheap, abundant. Just about every preparation I learned in Italy was handmade and involved learning how to use my own hands differently. … Food made by hand is an act of defiance and runs contrary to everything in our modernity. Find it; eat it; it will go.

This is exactly what I want from food writing: interesting nuggets of trivia and insight, a quick pace, humor, and mouthwatering descriptions. If the restaurant world lures you at all, you must read this one.

- Nice connections with my other summer reading: there are mentions of both Eric Asimov and Ruth Reichl visiting Babbo in their capacity as food critics for the New York Times.

- This also induced a weird case of reverse déjà vu: a book I reviewed last summer for BookBrowse, Hungry by Jeff Gordinier, is so similar that it must have been patterned on Heat: the punchy one-word title; a New York journalist follows an internationally known chef (in that case, René Redzepi) and surveys culinary trends.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

Source: From my dad

My rating:

The Gospel of Trees by Apricot Irving (2018)

(20 Books of Summer, #20) Irving’s parents were volunteer missionaries to Haiti between 1982 and 1991, when she was aged six to 15. Her father, Jon, was trained as an agronomist, and his passion was for planting trees to combat the negative effects of deforestation on the island (erosion and worsened flooding). But in a country blighted by political unrest, AIDS and poverty, people can’t think long-term; they need charcoal to light their stoves, so they cut down trees.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Irving drew on letters and cassette tape recordings, newsletters, and journals (her parents’ and her own) to recreate the decade in Haiti and the years since. This debut book was many years in the making – she started the project in 2001. “I inherited my father’s anger and his perfectionism. Haiti was a wound, an unhealed scab that I was afraid to pick open. But I knew that unless I faced that broken history, my own buried grief, like my father’s, would explode ways I couldn’t predict.”

She and her parents returned to the country after the 2010 earthquake: they were volunteers with a relief organization, while she reported for the This American Life radio program. I loved the ambivalent portrait of Haiti and, especially, of Jon, but couldn’t muster up much interest in secondary characters, hoped for more discussion of (loss of) faith, and thought the book about 80 pages too long. Irving writes wonderfully, though, especially when musing on Haiti’s pre-Columbian history; I’d gladly read a nature book about her life in Oregon, or a novel – in tone this reminded me of The Poisonwood Bible.

Some favorite lines:

If, like my father, you suffer from a savior complex, Haiti is a bleak assignment, but if you are able to enter it unguarded, shielded only by curiosity, you will find the sorrows entangled with a defiant joy.

My family had moved to Haiti to try to help, but instead, we learned our limitations. Failure can be a wise friend. We felt crushed at times; found it difficult to breathe; and yet the experience carved into each of us an understanding of loss, the weight of compassion. We learned how small we were when measured against the world’s great sorrow.

Source: Bargain book from Amazon last year

My rating:

And a DNF:

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

I gave up after 38 pages. I’ve long meant to try Oates, but her oeuvre is daunting. An Oprah’s Book Club selection seemed like a safe bet. I found the quirky all-American family saga approach somewhat similar to John Irving or Richard Russo, but Judd’s narration is annoyingly perky, and already I was impatient to find out what happened to his sister Marianne on Valentine’s Day 1976. I’ll give it a few years and try again. In the meantime, maybe I’ll try Oates in a different genre.

Looking back, Heat was the clear highlight of my 20 Books, closely followed by My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki. I also really enjoyed the foodoirs by Anthony Bourdain, Nina Mingya Powles and Luisa Weiss. It’s funny how much I love foodie lit given that I don’t cook. As Alice Steinbach puts it, “while we all like to eat, we like it more when someone else does the cooking.”

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread, Ella Minnow Pea. Ideally, I would not have had to include my two skims and one partial read in the total, but I ran out of time in August to substitute in three more books. I’m happy enough with my showing this year, but next time I plan to build in more flexibility – or cheating, whichever you wish to call it – to ensure that I manage 20 solid reads.

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread, Ella Minnow Pea. Ideally, I would not have had to include my two skims and one partial read in the total, but I ran out of time in August to substitute in three more books. I’m happy enough with my showing this year, but next time I plan to build in more flexibility – or cheating, whichever you wish to call it – to ensure that I manage 20 solid reads.

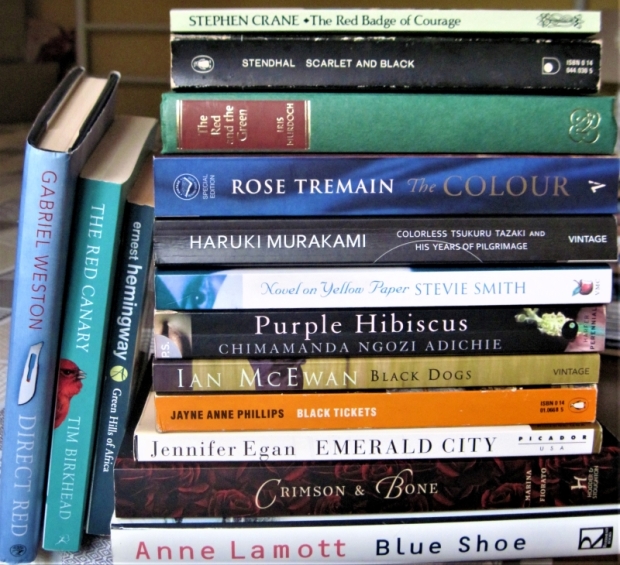

I already have a color theme planned for 20 Books of Summer 2021! Here are 15 books that I own, mostly fiction, that would fit the bill:

As wildcard selections and/or substitutes, I will also allow:

- Books with “light”, “dark”, or “bright” in the title

- Kindle or library books, though I’d like the focus to remain on print books I own.

- If I’m really stuck, book covers/jackets in a rainbow of colors. I’ll skip orange because Penguin paperbacks are too plentiful in my book collection, but I have some nice red, yellow, green, blue, purple and pink covers to choose from.