People Collide by Isle McElroy (Blog Tour)

People Collide (2023), nonbinary author Isle McElroy’s second novel, is a body swap story that explores the experiences and gender expectations of a heterosexual couple when they switch places. It’s not so much magic realism as a what-if experiment. Eli wakes up one morning in his wife Elizabeth’s body in their “pie slice of an apartment” in southern Bulgaria, where they moved for her government-sponsored teaching position. At first, finding himself alone, he thinks she’s disappeared and goes to the school to ask after her. The staff and students there, seeing him as Elizabeth, think they’re witnessing some kind of mental breakdown and send ‘her’ home. One of them is gone, yes, but it’s Elizabeth – in Eli’s body.

Both sets of parents get involved in the missing person case and, when a credit card purchase indicates Elizabeth is in Paris, Eli sets off after her. He is an apt narrator because he sees himself as malleable and inessential: “I wasn’t a person but a protean blob, intellectually and emotionally gelatinous, shaped by whatever surrounded me; “I could never shake the sense that I was, for [Elizabeth], like a supplementary arm grafted onto the center of her stomach.” He comes from a rough family background, has a history of disordered eating, and doesn’t have a career, so is mildly resentful of Elizabeth’s. She’s also an aspiring novelist and her solitary work takes priority while he cooks the meals and grades her students’ papers.

The couple already pushed against gender stereotypes, then, but it is still a revelation to Elizabeth how differently she is treated as a male. “I can’t name a single thing I don’t like about it. Everything’s become so much easier for me in your body,” she says to Eli when they finally meet up in Paris. There follows an arresting seven-page sex scene as they experience a familiar act anew in their partner’s body. “All that had changed was perspective.” But interactions with the partner’s parents assume primacy in much of the rest of the book.

This novel has an intriguing premise that offered a lot of potential, but it doesn’t really go anywhere with it. The sex scene actually struck me as the most interesting part, showing how being in a different body would help one understand desire. Beyond that, it feels like a stale rumination on passing as female (Elizabeth schooling Eli about menstruation and how to respond to her parents’ news about extended family) and women not being taken seriously in the arts (a lecture by a Rachel Cusk-like writer in the final chapter). I also couldn’t account for two unusual authorial decisions: Eli is caught up in a Parisian terrorist attack, but nothing results. Was it to shake things up at the one-third point, for want of a better idea? I also questioned the late shift to Elizabeth’s mother’s narration. Introducing a new first-person narrator, especially so close to the end, feels like cheating, or admitting defeat if there’s something important that Eli can’t witness. The author is skilled at creating backstory and getting characters from here to there. But in figuring out how the central incident would play out, the narrative falls short. Ultimately, I would have preferred this at short story length, where suggestion would be enough and more could have been left to the imagination.

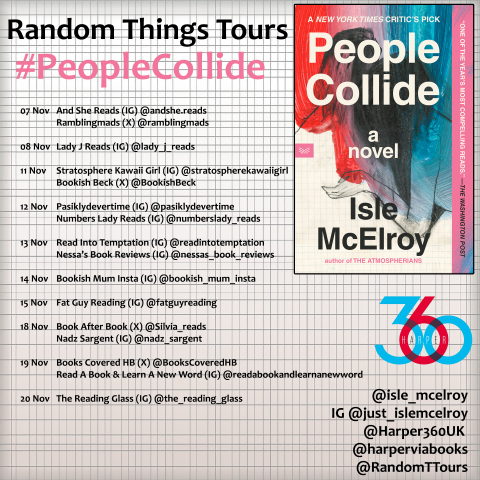

With thanks to Anne Cater of Random Things Tours and HarperVia for the free copy for review.

Buy People Collide from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for People Collide. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will appear soon.

#WITMonth, Part II: Wioletta Greg, Dorthe Nors, Almudena Sánchez and More

My next four reads for Women in Translation month (after Part I here) were, again, a varied selection: a mixed volume of family history in verse and fragmentary diary entries, a set of nature/travel essays set mostly in Denmark, a memoir of mental illness, and a preview of a forthcoming novel about Mary Shelley’s inspirations for Frankenstein. One final selection will be coming up as part of my Love Your Library roundup on Monday.

(20 Books of Summer, #13)

Finite Formulae & Theories of Chance by Wioletta Greg (2014)

[Translated from the Polish by Marek Kazmierski]

I loved Greg’s Swallowing Mercury so much that I jumped at the chance to read something else of hers in English translation – plus this was less than half price AND a signed copy. I had no sense of the contents and might have reconsidered had I known a few things: the first two-thirds is family wartime history in verse, the rest is a fragmentary diary from eight years in which Greg lived on the Isle of Wight, and the book is a bilingual edition, with Polish and English on facing pages (for the poems) or one after the other (for the diary entries). I’m not sure what this format adds for English-language readers; I can’t know whether Kazmierski has rendered anything successfully. I’ve always thought it must be next to impossible to translate poetry, and it’s certainly hard to assess these as poems. They are fairly interesting snapshots from her family’s history, e.g., her grandfather’s escape from a stalag, and have quite precise vocabulary for the natural world. There’s also been an attempt to create or reproduce alliteration. I liked the poem the title phrase comes from, “A Fairytale about Death,” and “Readers.” The short diary entries, though, felt entirely superfluous. (New purchase – Waterstones bargain, 2023)

I loved Greg’s Swallowing Mercury so much that I jumped at the chance to read something else of hers in English translation – plus this was less than half price AND a signed copy. I had no sense of the contents and might have reconsidered had I known a few things: the first two-thirds is family wartime history in verse, the rest is a fragmentary diary from eight years in which Greg lived on the Isle of Wight, and the book is a bilingual edition, with Polish and English on facing pages (for the poems) or one after the other (for the diary entries). I’m not sure what this format adds for English-language readers; I can’t know whether Kazmierski has rendered anything successfully. I’ve always thought it must be next to impossible to translate poetry, and it’s certainly hard to assess these as poems. They are fairly interesting snapshots from her family’s history, e.g., her grandfather’s escape from a stalag, and have quite precise vocabulary for the natural world. There’s also been an attempt to create or reproduce alliteration. I liked the poem the title phrase comes from, “A Fairytale about Death,” and “Readers.” The short diary entries, though, felt entirely superfluous. (New purchase – Waterstones bargain, 2023)

(20 Books of Summer, #14)

A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast by Dorthe Nors (2021; 2022)

[Translated from the Danish by Caroline Waight]

Nors’s first nonfiction work is a surprise entry on this year’s Wainwright Prize nature writing shortlist. I’d be delighted to see this work in translation win, first because it would send a signal that it is not a provincial award, and secondly because her writing is stunning. Like Patrick Leigh Fermor, Aldo Leopold or Peter Matthiessen, she doesn’t just report what she sees but thinks deeply about what it means and how it connects to memory or identity. I have a soft spot for such philosophizing in nature and travel writing.

Nors’s first nonfiction work is a surprise entry on this year’s Wainwright Prize nature writing shortlist. I’d be delighted to see this work in translation win, first because it would send a signal that it is not a provincial award, and secondly because her writing is stunning. Like Patrick Leigh Fermor, Aldo Leopold or Peter Matthiessen, she doesn’t just report what she sees but thinks deeply about what it means and how it connects to memory or identity. I have a soft spot for such philosophizing in nature and travel writing.

You carry the place you come from inside you, but you can never go back to it.

I longed … to live my brief and arbitrary life while I still have it.

This eternal, fertile and dread-laden stream inside us. This fundamental question: do you want to remember or forget?

Nors lives in rural Jutland – where she grew up, before her family home was razed – along the west coast of Denmark, the same coast that reaches down to Germany and the Netherlands. In comparison to Copenhagen and Amsterdam, two other places she’s lived, it’s little visited and largely unknown to foreigners. This can be both good and bad. Tourists feel they’re discovering somewhere new, but the residents are insular – Nors is persona non grata for at least a year and a half simply for joking about locals’ exaggerated fear of wolves.

Local legends and traditions, bird migration, reliance on the sea, wanderlust, maritime history, a visit to church frescoes with Signe Parkins (the book’s illustrator), the year’s longest and shortest days … I started reading this months ago and set it aside for a time, so now find it difficult to remember what some of the essays are actually about. They’re more about the atmosphere, really: the remote seaside, sometimes so bleak as to seem like the ends of the earth. (It’s why I like reading about Scottish islands.) A bit more familiarity with the places Nors writes about would have pushed my rating higher, but her prose is excellent throughout. I also marked the metaphors “A local woman is standing there with a hairstyle like a wolverine” and “The sky looks like dirty mop-water.”

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the proof copy for review.

Pharmakon by Almudena Sánchez (2021; 2023)

[Translated from the Spanish by Katie Whittemore]

This is a memoir in micro-essays about the author’s experience of mental illness, as she tries to write herself away from suicidal thoughts. She grew up on Mallorca, always feeling like an outsider on an island where she wasn’t a native. Did her depression stem from her childhood, she wonders? She is also a survivor of ovarian cancer, diagnosed when she was 16. As her mind bounces from subject to subject, “trying to analyze a sick brain,” she documents her doctor visits, her medications, her dreams, her retweets, and much more. She takes inspiration from famous fellow depressives such as William Styron and Virginia Woolf. Her household is obsessed with books, she says, and it’s mostly through literature that she understands her life. The writing can be poetic, but few pieces stand out on the whole. My favourite opens: “Living in between anxiety and apathy has driven me to flowerpot decorating.”

This is a memoir in micro-essays about the author’s experience of mental illness, as she tries to write herself away from suicidal thoughts. She grew up on Mallorca, always feeling like an outsider on an island where she wasn’t a native. Did her depression stem from her childhood, she wonders? She is also a survivor of ovarian cancer, diagnosed when she was 16. As her mind bounces from subject to subject, “trying to analyze a sick brain,” she documents her doctor visits, her medications, her dreams, her retweets, and much more. She takes inspiration from famous fellow depressives such as William Styron and Virginia Woolf. Her household is obsessed with books, she says, and it’s mostly through literature that she understands her life. The writing can be poetic, but few pieces stand out on the whole. My favourite opens: “Living in between anxiety and apathy has driven me to flowerpot decorating.”

With thanks to Fum d’Estampa Press for the free copy for review.

And a bonus preview:

Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein by Anne Eekhout (2021; 2023)

[Translated from the Dutch by Laura Watkinson]

Anne Eekhout’s fourth novel and English-language debut is an evocative recreation of two momentous periods in Mary Shelley’s life that led – directly or indirectly – to the composition of her 1818 masterpiece. Drawing parallels between the creative process and motherhood and presenting a credibly queer slant on history, the book is full of eerie encounters and mysterious phenomena that replicate the Gothic science fiction tone of Frankenstein itself. The story lines are set in the famous “Year without a Summer” of 1816 (the storytelling challenge with Lord Byron) and during a period in 1812 that she spent living in Scotland with the Baxter family; Mary falls in love with the 17-year-old daughter, Isabella.

Anne Eekhout’s fourth novel and English-language debut is an evocative recreation of two momentous periods in Mary Shelley’s life that led – directly or indirectly – to the composition of her 1818 masterpiece. Drawing parallels between the creative process and motherhood and presenting a credibly queer slant on history, the book is full of eerie encounters and mysterious phenomena that replicate the Gothic science fiction tone of Frankenstein itself. The story lines are set in the famous “Year without a Summer” of 1816 (the storytelling challenge with Lord Byron) and during a period in 1812 that she spent living in Scotland with the Baxter family; Mary falls in love with the 17-year-old daughter, Isabella.

Coming out on 3 October from HarperVia. My full review for Shelf Awareness is pending.

Recent BookBrowse & Shiny New Books Reviews, and Book Club Ado

Excerpts from and links to some of my recent online writing for other places:

BookBrowse

Three O’Clock in the Morning by Gianrico Carofiglio

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Shiny New Books

Notes from Deep Time: The Hidden Stories of the Earth Beneath Our Feet by Helen Gordon

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

My book club has been meeting via Zoom since April 2020. This is a common state of affairs for book clubs around the world. Especially since we have 12 members (if everyone attends, which is rare), we haven’t been able to contemplate meeting in person as of yet. However, a subset of us meet midway between the monthly reads to discuss women’s classics like Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time. For next week’s meeting on Mrs. Dalloway, we are going to attempt a six-person get-together in one member’s house.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

UnPresidented is the third book he wrote over the course of the Trump presidency. It started off as a diary of the 2020 election campaign, beginning in July 2019, but of course soon morphed into something slightly different: a chronicle of life in D.C. and London during Covid-19 and a record of the Trump mishandling of the pandemic. But as well as a farcical election process and a public health crisis, 2020’s perfect storm also included economic collapse and social upheaval – thanks to the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests worldwide plus isolated rioting.

UnPresidented served as a good reminder for me of the timeline of events and the full catalogue of outrages committed by Trump and his cronies. You just have to shake your head over the litany of ridiculous things he said and did, and got away with – any one of which might have sunk another president or candidate. The style is breezy and off-the-cuff, so the book reads quickly. There’s a good balance between world events and personal ones, with his family split across the UK and Australia. I appreciated the insight into differences from the British system. I thought it would be depressing reading back through the events of 2020, but for the most part the knowledge that everything turned out “right” allowed me to see the humour in it. Still, I found it excruciating reading about the four days following the election.

Sopel kindly gave us an hour of his time one Wednesday evening before he had to go on air and answered our questions about Biden, Harris, journalistic ethics, and more. He was charming and eloquent, as befits his profession.