Tag Archives: House of Anansi Press

#DoorstoppersInDecember: Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood & The End of Mr. Y by Scarlett Thomas

Later than intended, I’m reporting back on Margaret Atwood’s memoir, which I started in late November, and a long-neglected 500+-page novel I plucked from my shelves. Both offered page-turning intrigue and a blend of history, magic, and pure weirdness. Many thanks to Laura for hosting Doorstoppers in December, which encouraged me to pick them up!

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood (2025)

I gave some initial thoughts about the book here to tie in with Margaret Atwood Reading Month. What I said then proved true of the book as a whole: it’s delightful though dense with detail and historical context. I did get a little bogged down in the names and details of decades worth of publishing, but there is some tasty gossip, such as the fact that Margaret Laurence spread mean rumours about her (and was a drunk) but later changed her ways. It’s been a lucky window of time for Atwood to live through: she has known simplicity and the need for do-it-yourself practicality, but has also experienced privilege, even luxury (multiple homes and worldwide travel). Mostly, she had the good fortune of being at the start of Canada’s literary boom. In the early 1960s, only five Canadian novels were published per year. Through her involvement with literary magazines and House of Anansi Press and her books on Susanna Moodie and the tropes of Canadian literature, she helped create the scene.

I gave some initial thoughts about the book here to tie in with Margaret Atwood Reading Month. What I said then proved true of the book as a whole: it’s delightful though dense with detail and historical context. I did get a little bogged down in the names and details of decades worth of publishing, but there is some tasty gossip, such as the fact that Margaret Laurence spread mean rumours about her (and was a drunk) but later changed her ways. It’s been a lucky window of time for Atwood to live through: she has known simplicity and the need for do-it-yourself practicality, but has also experienced privilege, even luxury (multiple homes and worldwide travel). Mostly, she had the good fortune of being at the start of Canada’s literary boom. In the early 1960s, only five Canadian novels were published per year. Through her involvement with literary magazines and House of Anansi Press and her books on Susanna Moodie and the tropes of Canadian literature, she helped create the scene.

There are frequent mentions of how people or events made their way into her fiction and poetry. Coyly, she writes, “I just have a teeming imagination. Also, like all novelists, I’m a kleptomaniac.” The page or two of context on each book is illuminating and it never becomes the tedious “I published this book … then I published this book” that she mentioned wanting to avoid in the introduction. Rather, these sections made me want to go reread lots of her books to appreciate them anew. I was also reminded how often she’s been ahead of her time, with topics and details that seem prophetic (she proposed Payback before the financial crisis hit, for instance). Some elements felt particularly timely: she experienced casual misogyny and an alarming number of near-misses – she says things like “I won’t give his name … you know who you are … though you’re probably dead” – and, through her involvement in bird conservation, she’s well aware of the disastrous environmental trajectory we’re on.

For a memoir, this is not especially forthcoming about the author’s inner life and emotions. Where it is, she masks the material in a layer of technique. So when she’s confessing to having an affair while married to Jim Polk (whom she met at Harvard), she writes it like a fairytale scene in which she went into the woods with a wolf. When she was fretting about Graeme Gibson’s reluctance to divorce her first wife and marry her, she imagines letters to her ‘inner advice columnist’. (Note: Gibson was her long-time partner and his sons were like her stepchildren but they never did marry – and he only ‘allowed’ her the one child, though she wanted two of her own. One ‘Jess Gibson’ has a speculative short story collection, The Good Eye, coming out in May 2026. No doubt her work will be compared with her mother’s, but bully for her for not using the name Atwood to try to ride her coattails.)

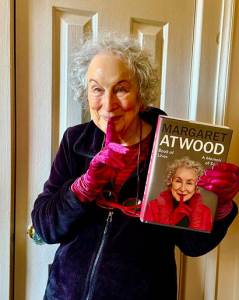

A cute pic from her Substack in November

One of the successful literary touches is the recurring “We Nearly Lose Graeme” segments about his risky behaviour and various mishaps. He had dementia and mini strokes before suffering a major one while in London with her for The Testaments tour; he died five days later. Her reflections on his death are poignant, but generic: “We can all believe three things simultaneously: The person is in the ground. The person is in the Afterlife. The person is in the next room. You keep expecting to see him. Even when you know it’s coming, a death is a shock.” At the crucial moment, she turns to the first-person plural and the second person.

I skimmed some of the bits about Graeme’s earlier life and the behind-the-scenes of publishing; I felt that he and many of her literary pals are more important to her than they are to readers. But that’s okay. The same goes for her earlier life; I noted that the account of her time as a summer camp counsellor felt more detailed than necessary. However, with her gift for storytelling, even the smallest incident can be rendered amusing. She looks for the humour, coincidence, or irony in any situation, and her summations and asides are full of dry humour. Some examples:

- “Spoiler: Jim and I eventually got married, one of the odder things to happen to both of us.”

- “After a while, the hand [at the window of her Harvard student accommodation] went away. It’s what you wish for in a disembodied hand.”

- “Eventually the iguana [inherited from her roommate] was given a new home at a zoo among other iguanas, where it was probably happier. Hard to tell.”

It’s not a book for the casual reader who kinda liked one or two Atwood novels; it’s more for the diehard fans among us, and offers a veritable trove of stories and photographs. But don’t expect a tell-all. Think of this more as a companion to her oeuvre. The title feels literal in that it’s as if she’s lived several lives: the wilderness kid, the literary ingénue, the family and career woman, the philanthropist and elder stateswoman. She doesn’t try to pull all of her incarnations into one, instead leaving all of the threads trailing into the beyond. If anything, “Peggy Nature” (her name from summer camp) is the role that has persisted. I probably liked the childhood material most, which makes sense as it’s what she’s looking back on with most fondness. Towards the close, Atwood mentions her heart condition and seems perfectly accepting of the fact that she won’t be around for much longer. But her body of work will endure. I’m so grateful for it and for the gift of this self-disclosure, however coy. (Can I be greedy and hope for another novel?) She leaves this message: “We scribes and scribblers are time travellers: via the magic page we throw our voices, not only from here to elsewhere, but also from now to a possible future. I’ll see you there.” [570 pages] (Public library) ![]()

The End of Mr. Y by Scarlett Thomas (2006)

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions.

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions.

The plot is pretty bonkers and I’m not sure I can satisfactorily explain its internal logic now, but as is true of the best doorstoppers, it absorbed me completely. I read it very quickly (for me) and even read 120 pages in one sitting thanks to my cat pinning me to the sofa. It also felt prescient in discussing “machine consciousness” – a topic adjacent to artificial intelligence. Ariel is a Disaster Woman avant la lettre, living on noodles and cut-price wine. Her current ‘relationship’ consisting of rough sex with a married professor is the latest in a string of unhealthy connections. But time travel offers the possibility not just of reversing her own mistakes, but of going right back to the start of humanity. Verging on steampunk, this was much better than the other Thomas novels I’ve read, The Seed Collectors and Oligarchy. It was longlisted for the Orange (Women’s) Prize and would be a great choice for readers of Nicola Barker and Susanna Clarke. [502 pages] (Secondhand – Book-Cycle, Exeter; it’s been on my shelves since 2016!) ![]()

Carol Shields Prize Longlist Reading: The Future and Chrysalis

My first two dedicated reads for our informal Carol Shields Prize shadowing project exhibit one main way in which the prize is different from the Women’s Prize for Fiction: works in translation and short story collections are eligible. I have one of each to review today. Laura and I did a buddy read of an atmospheric dystopian novel translated from the French, and I caught up on a magical, erotic story collection I’d had on my Kindle for a long time. These were both very good, but my minor misgivings are such that I’d rate them the same: ![]()

The Future by Catherine Leroux (2020; 2023)

[Translated from the French by Susan Ouriou]

For such a monolithic title, this has a limited stage: a few derelict districts of the ailing city we know as Detroit, Michigan – but in Leroux’s alternate version, it remained part of French Canada, with lingering Indigenous influence, and so is known as Fort Détroit. No doubt she was inspired by the many vacant properties that characterized Detroit in the 2010s; there’s even a ruins tour bus. In her Fort Détroit, a handful of determined adults cling on in their own homes, but the streets and parks have been abandoned to animals and to a gang of half-feral children who have developed their own nicknames (Adidas, Lego, Wolfpup), social hierarchy and vernacular. Worlds meet when Gloria determines to find her granddaughters Cassandra and Mathilda, who ran away after their addict mother Judith’s suspicious death. At the same time, her neighbour Eunice wants to find out who ran her father down in the street.

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age.

Despite their fierce independence and acts of protest, the novel’s children still rely on the adult world. Ecosystems are awry and the river is toxic, but Gloria’s friend Solomon, a former jazz pianist, still manages to grow crops. He overlooks the children’s thefts from his greenhouse and eventually offers to help them grow their own food supply, and other adults volunteer to prepare a proper winter shelter to replace their shantytown. Puberty threatens their society, too: we learn that Fiji, the leader, has been binding her breasts to hide her age.

I expected to be reminded strongly of Station Eleven, and while there were elements that were reminiscent of Emily St John Mandel’s work, Leroux’s is a more consciously literary approach. The present-tense omniscient narration occupies many perspectives, including that of a dog, and the descriptions and musings are more lyrical than literal. Where another author would site high drama – sixtysomething Gloria’s night quest, a few children rafting down the river – Leroux moves on swiftly to other character interactions. What did bring Mandel to mind was the importance of art during societal collapse: the children spin nursery rhyme mash-ups and fairytales, Stutt rescues a makeshift library and insists on Huckleberry Finn going along on the river journey, and Solomon plays the piano again after decades.

The opening mysteries of death and disappearance are resolved before the end, but don’t seem to have been the point. The Future is more subtle and slippery than many dystopian novels I’ve read in that there’s not really a warning, or a message here. Instead, there’s an intriguing situation that opens out and alters slightly, but avoids resolution. It’s all about atmosphere and language – I was especially impressed by Ouriou’s rendering of Leroux’s made-up dialect via folksy slang (“She figgers she’s growed-up”). I loved the details and one-on-one moments more than the momentous scenes. On the whole, I found the story elegant but somewhat frustrating. You might be drawn to it if you enjoyed To Paradise or the MaddAddam books. (Read via Edelweiss; published by Biblioasis)

See also Laura’s review.

Chrysalis: Stories by Anuja Varghese (2023)

This debut collection of 15 stories brims with magic and horror, and teems with women of colour and queer people. Indeed, Varghese dedicates the book to “all the girls and women who don’t see themselves in most stories.” Most of the characters are of South Asian extraction. Adoption recurs in a couple of places. Two of the rarer realist stories, “Milk” and “Stories in the Language of the Fist,” have protagonists dealing with schoolgirl bullying and workplace microaggressions. More often, there are unexplained phenomena that position the players between life and death. “In the Bone Fields” focuses on the twin daughters of an Indian immigrant family on a Canadian farm. The house and the bone field behind are active and hungry, and only one twin will survive. (I got mild North Woods vibes.)

In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).

In the title story, Radhika visits her mother’s grave and wonders whether her life is here in Montreal with her lover or back in Toronto with her husband. Fangs and wings symbolize her desire for independence. Elsewhere, watery metaphors alternately evoke fear of drowning or sexual fluidity. “Midnight at the Oasis” charts the transformation of a trans woman and “Cherry Blossom Fever,” one of my two favourites, bounces between several POVs. Marjan is in love with Talia, but she’s married to Sunil, who’s also in love with Silas. “People do it — open their relationships and negotiate rules and write themselves into polyamorous fairy tales … Other people. Not brown people,” Talia sighs. They are better off, at least, than they would be back in India, where homophobia can be deadly (“The Vetala’s Song”).

My other favourite was “Bhupati,” about a man who sets up multiple Lakshmi figures in the backyard, hoping devotion will earn him and his wife a better future. The statues keep being burned up by lightning; we learn his wife may be petitioning for different things. “Chitra” is a straightforward Cinderella retelling whose title character lives with two mean stepsisters and works in food service at the mall. A Shoe Chateau BOGO closing sale gives her the chance to get a bargain – and catch the manager’s eye. Despite a striking ending signalled by the story’s subtitle, all I could conclude about this one was “cute.” The three flash horror stories (a murder hotel, ghosts in a basement, werewolves) were much the weakest for me.

There’s a pretty even split of third- and first-person stories (nine versus six) here, and the genre shifts frequently. The quality wasn’t as consistent as I’d hoped, but it was an engaging read. The overall blend of feminism and horror had me thinking of Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado, but I’d be most likely to recommend this to fans of Julia Armfield, Violet Kupersmith and Vauhini Vara. (Read via Edelweiss; published by House of Anansi Press)

Both of these are worthwhile books and it’s great that readers outside of Canada can discover them. I wouldn’t personally shortlist either, but the judges may well be dazzled enough to do so. I don’t yet have a sense of where they’d fit for me in the rankings.

Up next:

Cocktail by Lisa Alward (short story collection from Edelweiss)

A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power (buddy read with Laura)

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang (from library)

I’m aiming for one or two more batches of reviews before the shortlist is announced on 9 April.