Three on a Theme: Armchair Travels at the Italian Coast (Rachel Joyce, Sarah Moss and Jess Walter – #18 of 20 Books)

I’ve done a lot of journeying through Italy’s lakes and islands this summer. Not in real life, thank goodness – it would be far too hot! – but via books. I started with the Moss, then read the Joyce, and rounded off with the Walter, a book that had been on my TBR for 12 years and that many had heartily recommended, so I was delighted to finally experience it for myself.

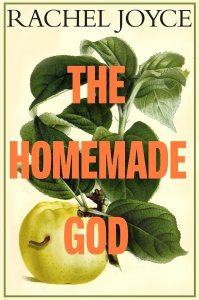

The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce (2025)

Joyce has really upped her game. I’ve somehow read all of her books though I often found them, from Harold Fry onward, disappointingly sentimental and twee. But with this she’s entering the big leagues, moving into the more expansive, elegant and empathetic territory of novels by Anne Enright (The Green Road), Patrick Gale (Notes from an Exhibition), Maggie O’Farrell (Instructions for a Heatwave) and Tom Rachman (The Italian Teacher). It’s the story of four siblings, initially drawn together and then dramatically blown apart by their father’s death. Despite weighty themes of alcoholism, depression and marital struggles, there is an overall lightness of tone and style that made this a pleasure to read.

Vic Kemp, the title figure, was a larger-than-life, womanizing painter whose work divided critics. After his first wife’s early death from cancer, he raised three daughters and a son with the help of a rotating cast of nannies (whom he inevitably slept with). At 76 he delivered the shocking news that he was marrying again: Bella-Mae, an artist in her twenties – much younger than any of his children. They moved from London to his second home in Italy just weeks before he drowned in Lake Orta. Netta, the eldest daughter, is sure there’s something fishy; he knew the lake so well and would never have gone out for a swim with a mist rolling in. Did Bella-Mae kill him for his money? And where is his last painting? Funny how waiting for an autopsy report and searching for a new will and carping with siblings over the division of belongings can ruin what should be paradise.

The interactions between Netta, Susan, Goose (Gustav) and Iris, plus Bella-Mae and her cousin Laszlo, are all flawlessly done, and through flashbacks and surges forward we learn so much about these flawed and flailing characters. The derelict villa and surrounding small town are appealing settings, and there are a lot of intriguing references to food, fashion and modern art.

My only small points of criticism are that Iris is less fleshed out than the others (and her bombshell secret felt distasteful), and that Joyce occasionally resorts to delivering some of her old obvious (though true) messages through an omniscient narrator, whereas they could be more palatable if they came out organically in dialogue or indirectly through a character’s thought process. Here’s an example: “When someone dies or disappears, we can only tell stories about what might have been the case or what might have happened next.” (One I liked better: “There were some things you never got over. No amount of thinking or talking would make them right: the best you could do was find a way to live alongside them.”) I also don’t think Goose would have been able to view his father’s body more than two months after his death; even with embalming, it would have started to decay within weeks.

You can tell that Joyce got her start in theatre because she’s so good at scenes and dialogue, and at moving people into different groups to see what they’ll do. She’s taken the best of her work in other media and brought it to bear here. It’s fascinating how Goose starts off seeming minor and eventually becomes the main POV character. And ending with a wedding (good enough for a Shakespearean comedy) offers a lovely occasion for a potential reconciliation after a (tragi)comic plot. More of this calibre, please! (Public library) ![]()

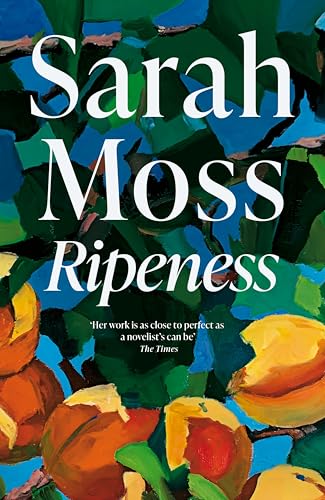

Ripeness by Sarah Moss (2025)

One sneaky little line, “Ripeness, not readiness, is all,” a Shakespeare mash-up (“Ripeness is all” is from King Lear vs. “the readiness is all” is from Hamlet), gives a clue to how to understand this novel: As a work of maturity from Sarah Moss, presenting life with all its contradictions and disappointments, not attempting to counterbalance that realism with any false optimism. What do we do, who will we be, when faced with situations for which we aren’t prepared?

Now that she’s based in Ireland, Moss seems almost to be channelling Irish authors such as Claire Keegan and Maggie O’Farrell. The line-up of themes – ballet + sisters + ambivalent motherhood + the question of immigration and belonging – should have added up to something incredible and right up my street. While Ripeness is good, even very good, it feels slightly forced. As has been true with some of Moss’s recent fiction (especially Summerwater), there is the air of a creative writing experiment. Here the trial is to determine which feels closer, a first-person rendering of a time nearly 60 years ago, or a present-tense, close-third-person account of the now. [I had in mind advice from one of Emma Darwin’s Substack posts: “What you’ll see is that ‘deep third’ is really much the same as first, in the logic of it, just with different pronouns: you are locking the narrative into a certain character’s point-of-view, but you don’t have a sense of that character as the narrator, the way you do in first person.” Except, increasingly as the novel goes on, we are compelled to think about Edith as a narrator, of her own life and others’.

In the current story line, everyone in rural West Ireland seems to have come from somewhere else (e.g. Edith’s lover Gunter is German). “She’s going to have to find a way to rise above it, this tribalism,” Edith thinks. She’s aghast at her town playing host to a small protest against immigration. Fair enough, but including this incident just seems like an excuse for some liberal handwringing (“since it’s obvious that there is enough for all, that the problem is distribution not supply, why cannot all have enough? Partly because people like Edith have too much.”). The facts of Maman being French-Israeli and having lost family in the Holocaust felt particularly shoehorned in; referencing Jewishness adds nothing. I also wondered why she set the 1960s narrative in Italy, apart from novelty and personal familiarity. (Teenage Edith’s high school Italian is improbably advanced, allowing her to translate throughout her sister’s childbirth.)

Though much of what I’ve written seems negative, I was left with an overall favourable impression. Mostly it’s that the delivery scene and the chapters that follow it are so very moving. Plus there are astute lines everywhere you look, whether on dance, motherhood, or migration. It may simply be that Moss was taking on too much at once, such that this lacks the focus of her novellas. Ultimately, I would have been happy to have just the historical story line; the repeat of the surrendering for adoption element isn’t necessary to make any point. (I was relieved, anyway, that Moss didn’t resort to the cheap trick of having the baby turn out to be a character we’ve already been introduced to.) I admire the ambition but feel Moss has yet to return to the sweet spot of her first five novels. Still, I’m a fan for life. (Public library) ![]()

#18 of my 20 Books of Summer

(Completing the second row on the Bingo card: Book set in a vacation destination)

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter (2012)

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I loved how Emma Straub described the ideal summer read in one of her Substack posts: “My plan for the summer is to read as many books as possible that make me feel that drugged-up feeling, where you just want to get back to the page.” I wish I’d been able to read this faster – that I hadn’t had so much on my plate all summer so I could have been fully immersed. Nonetheless, every time I returned to it I felt welcomed in. So many trusted bibliophiles love this book – blogger friends Laila and Laura T.; Emma Milne-White, owner of Hungerford Bookshop, who plugged it at their 2023 summer reading celebration; and Maris Kreizman, who in a recent newsletter described this as “One of my favorite summer reading novels ever … escapist magic, a lush historical novel.”

I’m relieved to report that Beautiful Ruins lived up to everyone’s acclaim – and my own high expectations after enjoying Walter’s So Far Gone, which I reviewed for BookBrowse earlier in the summer. I was immediately captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. With refreshing honesty, he’s dubbed the place “Hotel Adequate View.” In April 1962, he’s attempting to build a cliff-edge tennis court when a boat delivers beautiful, dying American actress Dee Moray. It soon becomes clear that her condition is nothing nine months won’t fix and she’s been dumped here to keep her from meddling in the romance between the leads in Cleopatra, filming in Rome. In the present day, an elderly Pasquale goes to Hollywood to find out whatever happened to Dee.

A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime masterpiece, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in that summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. True to the tone of a novel about regret, failure and shattered illusions, Walter doesn’t tie everything up neatly, but he does offer a number of the characters a chance at redemption. This felt to me like a warmer and more timeless version of A Visit from the Goon Squad. There are so many great scenes, none better than Richard Burton’s drunken visit to Porto Vergogna, which had me in stitches. Fantastic. (Hungerford Bookshop – 40th birthday gift from my husband from my wish list) ![]()

In Memoriam by Alice Winn: Review & Author Event

I read In Memoriam by Alice Winn last month, then had the chance to see the author in conversation at Hungerford Town Hall, an event hosted by Hungerford Bookshop, on Friday evening. Here’s what I thought of the novel, which is on my Best of 2023 list.

Review

Heartstopper on the Western Front; swoon! It’s literary fiction set in the trenches of WWI, yes, but also a will-they-won’t they romance that opens at an English boarding school. Oh they will (have sex, that is), before the one-third point, but the lingering questions are: will Sidney Ellwood and Henry Gaunt both acknowledge this is love and not just sex, as it is for many teenage boys at their school (either consensually, as buddies; or forced by bullies); and will one or both survive the war? “It was ridiculous, incongruous for Ellwood to be bandying about words like ‘love’ when they were preparing to venture out into No Man’s Land.”

Winn is barely past 30 (and looks like a Victorian waif in her daguerreotype-like author photo), yet keeps a tight control of her tone and plot in this debut novel. She depicts the full horror of war, with detailed accounts of battles at Loos, Ypres and the Somme, and the mental health effects on soldiers, but in between there is light-heartedness: banter, friendship, poetry. Some moments are downright jolly. I couldn’t help but laugh at the fact that Adam Bede is the only novel available and most of them have read it four times. Gaunt is always the more pessimistic of the two, while Ellwood’s initially flippant sunniness darkens through what he sees and suffers.

I only learned from the Acknowledgements and Historical Note that Preshute is based on Marlborough College, a posh school local to me that Winn attended, and that certain particulars are drawn from Siegfried Sassoon, as well as other war literature. It’s clear the book has been thoroughly, even obsessively, researched. But Winn has a light touch with it, and characters who bring social issues into the narrative aren’t just 2D representatives of them but well rounded and essential: Gaunt (xenophobia), Ellwood (antisemitism), Hayes (classism), Devi (racism); not to mention disability and mental health for several.

I also loved how Ellwood is devoted to Tennyson and often quotes from his work, including the book-length elegy In Memoriam itself. This plus the “In Memoriam” columns of the school newspaper give the title extra resonance. I thought I was done with war fiction, but really what I was done with was worthy, redundant Faulks-ian war fiction. This was engaging, thrilling (a prison escape!), and, yes, romantic. (Public library)

Readalike: The New Life by Tom Crewe, another of my early favourites of 2023, is set in a similar time period and also considers homosexual relationships. It, too, has epistolary elements and feels completely true to the historical record.

Some favourite lines:

“If Ellwood were a girl, he might have held his hand, kissed his temple. He might have bought a ring and tied their lives together. But Ellwood was Ellwood, and Gaunt had to be satisfied with the weight of his head on his shoulder.”

“Gaunt wished the War had been what Ellwood wanted it to be. He wished they could have ridden across a battlefield on horseback, brandishing a sword alongside their gallant king. He put on his gas mask. His men followed.”

Buy In Memoriam from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

Event

Winn is in the UK on a short book tour; although she is English, she now lives in Brooklyn and recently had a baby. She was in conversation with AJ West, the author of The Spirit Engineer, also set on the cusp of WWI. Unrecognizable from her author photo – now blonde with glasses – she is petite rather than willowy. As I was leaving, two ladies remarked to each other how articulate she was. Indeed, she was well spoken and witty and, I expect, has always been precocious and a high achiever. I think she’s 32. Before this she wrote three novels that remain unpublished. She amazed us all by admitting she wrote the bulk of In Memoriam in just two weeks, pausing only to research trench warfare, then edited it for a year and a half.

West asked her about the genesis of the novel and she explained her obsession with the wartime newspapers of Sassoon’s school and then the letters sent home by soldiers, tracking the shift in tenor from early starry-eyed gallantry to feeling surrounded by death. She noted that it was a struggle for her to find a balance between the horrors of the Front and the fact that these young men come across in their written traces as so funny. She got that balance just right.

Was she being consciously anti-zeitgeist in focusing on privileged white men rather than writing women and minorities back into the narrative, as is so popular with publishers today, West asked? She demurred, but added that she wanted to achieve something midway between being of that time and a 2023 point-of-view in terms of the sexuality. Reading between the lines and from secondary sources, she posited that it was perhaps easier to get away with homosexuality than one might think, in that it wasn’t expected and so long as it was secret, temporary (before marrying a woman), or an experiment, it was tolerated. However, she took poetic licence in giving Gaunt and Ellwood supportive friends.

Speaking of … West (a gay man) jokingly asked Winn if she is actually a gay man, because she got their experiences and feelings spot on. She said that she has some generous friends who helped her with the authenticity of the sex scenes. In the novel she has Ellwood interpret Tennyson’s In Memoriam as crypto-homosexual, but scholars do not believe that it is; Gaunt’s twin sister Maud also, unconsciously in that case, has a Tennysonian name. This was in response to an audience question; this plus another one asking if Winn had read The New Life reassured me that my reaction was well founded! (Yes, she has, and will in fact be in conversation with Crewe in London on the 23rd. She’s also appearing at Hay Festival.)

If you’ve read the book and/or are curious, Winn revealed the inspirations for her three main characters, the real people who are “in their DNA,” as she put it: Gaunt = Robert Graves (half-German, interest in the Greek classics); Ellwood = Sassoon; Maud = Vera Brittain. She read a 5-minute passage incorporating a school scene between Gaunt and Sandys and a letter from the Front. She spoke a little too quickly and softly, such that I was glad I was within the first few rows. However, I’m sure this is a new-author thing and, should you be so lucky as to see her speak in future, you will be as impressed as I was.

Local Resistance: On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester

It’s mostly by accident that we came to live in Newbury: five years ago, when a previous landlord served us notice, we viewed a couple of rental houses in the area to compare with what was available in Reading and discovered that our money got us more that little bit further out from London. We’ve come to love this part of West Berkshire and the community we’ve found. It may not be flashy or particularly famous, but it has natural wonders worth celebrating and a rich history of rebellion that Nicola Chester plumbs in On Gallows Down. A hymn-like memoir of place as much as of one person’s life, her book posits that the quiet moments of connection with nature and the rights of ordinary people are worth fighting for.

So many layers of history mingle here: from the English Civil War onward, Newbury has been a locus of resistance for centuries. Nicola* has personal memories of the long-running women’s peace camps at Greenham Common, once a U.S. military base and cruise missile storage site – to go with the Atomic Weapons Establishment down the road at Aldermaston. As a teenager and young woman, she took part in symbolic protests against the Twyford Down and Newbury Bypass road-building projects, which went ahead and destroyed much sensitive habitat and many thousands of trees. Today, through local and national newspaper and magazine columns on wildlife, and through her winsome nagging of the managers of the Estate she lives on, she bears witness to damaging countryside management and points to a better way.

While there is a loose chronological through line, the book is principally arranged by theme, with experiences linked back to historical or literary precedents. An account of John Clare and the history of enclosure undergirds her feeling of the precarity of rural working-class life: as an Estate tenant, she knows she doesn’t own anything, has no real say in how things are done, and couldn’t afford to move elsewhere. Nicola is a school librarian and has always turned to books and writing to understand the world. I particularly loved Chapter 6, about how she grounds herself via the literature of this area: Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, Adam Thorpe’s Ulverton, and especially Richard Adams’s Watership Down.

Whatever life throws at her – her husband being called up to fight in Iraq, struggling to make ends meet with small children, a miscarriage, her father’s unexpected death – nature is her solace. She describes places and creatures with a rare intimacy borne out of deep knowledge. To research a book on otters for the RSPB, she seeks out every bridge over every stream. She goes out “lamping” with the local gamekeeper after dark and garners priceless nighttime sightings. Passing on her passion to her children, she gets them excited about badger watching, fossil collecting, and curating shelves of natural history treasures like skulls and feathers. She also serves as a voluntary wildlife advocate on her Estate. For every victory, like the re-establishment of the red kite population in Berkshire and regained public access to Greenham Common, there are multiple setbacks, but she continues to be a hopeful activist, her lyrical writing a means of defiance.

We are writing for our very lives and for those wild lives we share this one, lonely planet with. Writing was also a way to channel the wildness; to investigate and interpret it, to give it a voice and defend it. But it was also a connection between home and action; a plank bridge between a domestic and wild sense. A way both to home and resist.

You know that moment when you’re reading a book and spot a place you’ve been or a landmark you know well, and give a little cheer? Well, every site in this book was familiar to me from our daily lives and countryside wanderings – what a treat! As I was reading, I kept thinking how lucky we are to have such an accomplished nature writer to commemorate the uniqueness of this area. Even though I was born thousands of miles away and have moved more than a dozen times since I settled in England in 2007, I feel the same sense of belonging that Nicola attests to. She explicitly addresses this question of where we ‘come from’ versus where we fit in, and concludes that nature is always the key. There is no exclusion here. “Anyone could make a place their home by engaging with its nature.”

*I normally refer to the author by surname in a book review, but I’m friendly with Nicola from Twitter and have met her several times (and she’s one of the loveliest people you’ll ever meet), so somehow can’t bring myself to be that detached!

On Gallows Down was released by Chelsea Green Publishing on October 7th. My thanks to the author and publisher for arranging a proof copy for review.

My husband and I attended the book launch event for On Gallows Down in Hungerford on Saturday evening. Nicola was introduced by Hungerford Bookshop owner Emma Milne-White and interviewed by Claire Fuller, whose Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel Unsettled Ground is set in a fictional version of the village where Nicola lives.

Nicola Chester and Claire Fuller. Photo by Chris Foster.

Nicola dated the book’s genesis to the moment when, 25 years ago, she queued up to talk to a TV news reporter about Newbury Bypass and froze. She went home and cried, and realized she’d have to write her feelings down instead. Words generally come to her at the time of a sighting, as she thinks about how she would tell someone how amazing it was.

Her memories are tied up with seasons and language, especially poetry, she said, and she has recently tried her hand at poetry herself. Asked about her favourite season, she chose two, the in-between seasons – spring for its abundance and autumn for its nostalgia and distinctive smells like tar spot fungus on sycamore leaves and ivy flowers.

A bonus related read:

Anarchipelago by Jay Griffiths (2007)

This limited edition 57-page pamphlet from Glastonbury-based Wooden Books caught my eye from the library’s backroom rolling stacks. Griffiths wrote her impish story of Newbury Bypass resistance in response to her time among the protesters’ encampments and treehouses. Young Roddy finds a purpose for his rebellious attitude wider than his “McTypical McSuburb” by joining other oddballs in solidarity against aggressive policemen and detectives.

There are echoes of Ali Smith in the wordplay and rendering of accents.

“When I think of the road, I think of more and more monoculture of more and more suburbia. What I do, I do in defiance of the Louis Queasy Chintzy, the sickly stale air of suburban car culture. I want the fresh air of nature, the lifefull wind of the French revolution.”

In a nice spot of Book Serendipity, both this and On Gallows Down recount the moment when nature ‘fought back’ as a tree fell on a police cherry-picker. Plus Roddy is kin to the tree-sitting protesters in The Overstory by Richard Powers as well as another big novel I’m reading now, Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson.

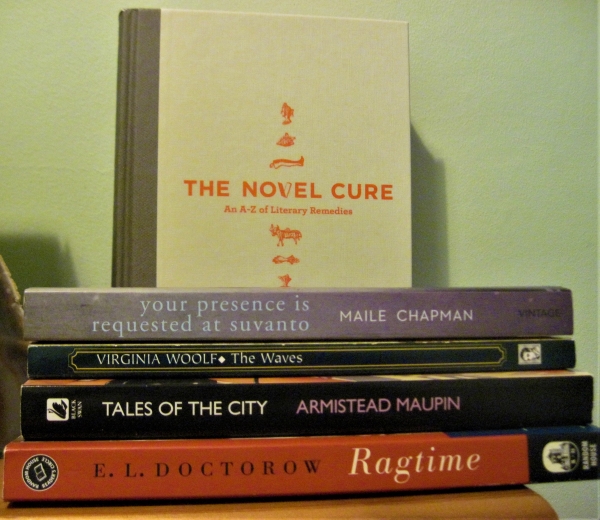

Book Spine Poetry Returns

The literary world continues to revolve, rapidly replacing all in-person events with online ones. On Thursday night I was meant to be in London seeing Anne Tyler. Instead, I spent the evening on Twitter, watching a literary prize announcement, attending two virtual book launches, and (pre)ordering three March releases from my nearest independent bookstore, Hungerford Bookshop. Today I sent the shop owner a long list of book recommendations for the website. I offered remote bibliotherapy for customers and she asked me to add to her curated lists of Long books, Books that are part of a big series, Books to make you laugh, and Books about hope (that last one was really hard). I’m also going to be taking part in two blog tours in early April for novels whose book tours were cancelled. A hint is below.

I’m continuing to read and write to the blog plan I had set up for March into April. What else is there to do? In the meantime, I assembled some titles, mostly from books on my bedside table, into a few impromptu poems. Remember what fun book spine poetry was back in 2016? (My efforts from that short-lived craze are here and here.)

A partial haiku for our times:

Plus two more wee poems of hope and lament.

Refuge

The song of the lark,

The nightingale

Abide with me

A sweet, wild note.

The Sorrows of an American

News of the world:

My own country,

Red at the bone.

I hope you are all staying safe and keeping your spirits up.

What have you been reading that has felt particularly appropriate or comforting?

Birthday Happenings

One of the best things about being a home-based freelancer is that I can arrange my work schedule to suit my life. Having my birthday fall on a Friday this year was especially good because it meant I got until Monday to submit my daily editing load. My husband was working as usual, so I spent much of the day reading under the cat and charity shopping. I bought seven books, a nice mixture of England-themed nonfiction and juicy novels, plus new-to-me comfy black flats. (Total spend: £10.25.) Being short on time that evening, we lazily ordered delivery pizza for probably the first time in eight years, followed by cocktails and cake.

I didn’t end up using my literary cakes and cocktails books this year, but that gives me a chance to proffer my own pun names for what we did make. We tried two gin cocktails we’d found recipes for in the Guardian. The one they called “Elderflower Collins” was absolutely delicious: lemon juice, elderflower cordial and gin, topped up with San Pellegrino Limonata (lemon soda) and garnished with a lemon slice and a mint sprig. I dub it “A Visit from Mr. Collins,” as in the Bennet girls will have to down quite a few of these before…

I didn’t end up using my literary cakes and cocktails books this year, but that gives me a chance to proffer my own pun names for what we did make. We tried two gin cocktails we’d found recipes for in the Guardian. The one they called “Elderflower Collins” was absolutely delicious: lemon juice, elderflower cordial and gin, topped up with San Pellegrino Limonata (lemon soda) and garnished with a lemon slice and a mint sprig. I dub it “A Visit from Mr. Collins,” as in the Bennet girls will have to down quite a few of these before…

Unfortunately, the second cocktail was not a hit. The “Miss Polly Hawkins” combines chamomile-flavored gin (I steeped two chamomile teabags in 60 mL of gin for a week), rose syrup (we didn’t have it or want to buy it so substituted our homemade rosehip syrup), plain gin and egg white. Egg white is a fairly frequent ingredient in cocktails – it adds gloss and body – but we found that it made the drink gloopy. That plus the overall floral and medicinal notes meant this was fairly hard to swallow; we had to drown it in sparkling water and ice cubes to get it down. Alas, I modify Iris Murdoch to call this “An Unappealing Rose.”

However, my cake was an unqualified success. I usually go for chocolate or chocolate/peanut butter desserts, but decided to be different this year and requested the Italian Pear and Ginger Cheesecake from Genevieve Taylor’s cookbook A Good Egg. It was sophisticated and delicious. Running with the Italy thing, I’ll pick out a Forster title and call it “Where Angels Pear to Tread.” (It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense; then again, neither do a lot of the names in Tequila Mockingbird and Scone with the Wind!)

However, my cake was an unqualified success. I usually go for chocolate or chocolate/peanut butter desserts, but decided to be different this year and requested the Italian Pear and Ginger Cheesecake from Genevieve Taylor’s cookbook A Good Egg. It was sophisticated and delicious. Running with the Italy thing, I’ll pick out a Forster title and call it “Where Angels Pear to Tread.” (It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense; then again, neither do a lot of the names in Tequila Mockingbird and Scone with the Wind!)

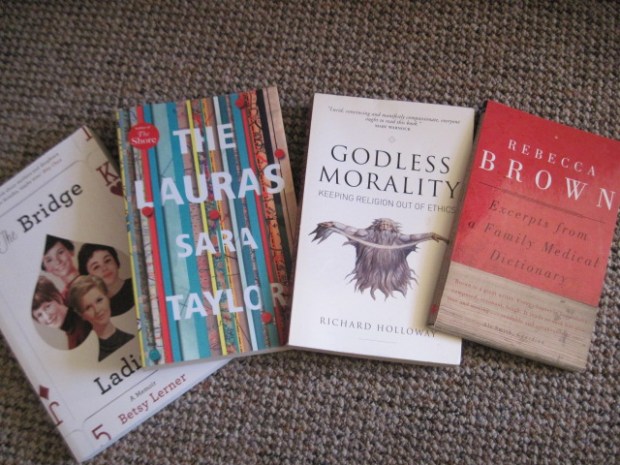

On Sunday the birthday fun continued with a trip to Hungerford Bookshop (our nearest independent bookshop) and a gentle country walk. I bought two secondhand books but came away with a total of four – in the basement they have a table covered in free proof copies, so my husband and I grabbed one each (how I wish I could have taken the lot!). It’s a great idea for rewarding customer loyalty and dealing with unwanted proofs; perhaps I’ll donate a stack of mine to them next time I’m there.

Two proofs (left) and two nonfiction purchases.

This year I got a Kindle case and two bookshop-themed memoirs as presents: The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap by Wendy Welch and Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs by Jeremy Mercer. I started reading the former – the story of a married couple opening a bookshop in recession-era Virginia – right away. I also got a poster frame so I can finally hang my literary map of the British Isles on the wall above my desk, and a “Shhhh, reading in progress” mug.

Consuming tasty food and drink + acquiring a baker’s dozen of books + getting out into the countryside = a great birthday weekend!

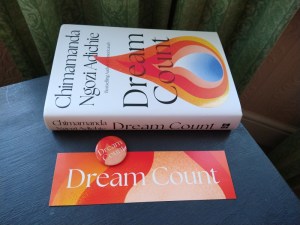

Why four main characters? Why is it the one non-Nigerian who’s poor, victimized, and less proficient in English? (That Kadiatou is based on a real person doesn’t explain enough. Her plight does at least provide what plot there is.) Why are the other three, to varying extents, rich and pretentious? Why are two narratives in the first person and two in the third person? Why in such long chunks instead of switching the POV more often? Why so many men, all of them more or less useless? (All these heterosexual relationships – so boring!) Why bring Covid into it apart from for verisimilitude? But why is the point in time important? What point is she trying to convey about pornography, the subject of Omelogor’s research?

Why four main characters? Why is it the one non-Nigerian who’s poor, victimized, and less proficient in English? (That Kadiatou is based on a real person doesn’t explain enough. Her plight does at least provide what plot there is.) Why are the other three, to varying extents, rich and pretentious? Why are two narratives in the first person and two in the third person? Why in such long chunks instead of switching the POV more often? Why so many men, all of them more or less useless? (All these heterosexual relationships – so boring!) Why bring Covid into it apart from for verisimilitude? But why is the point in time important? What point is she trying to convey about pornography, the subject of Omelogor’s research? The Hotel is a fenland folly, built on the site of a pond where a suspected witch was drowned. Ever after, it is a cursed place. Those who build the hotel and stay in it are subject to violence, fear, and eruptions of the unexplained – especially if they go in Room 63. Anyone who visits once seems doomed to return. Most of the stories are in the first person, which makes sense for dramatic monologues. The speakers are guests, employees, and monsters. Some are BIPOC or queer, as if to tick off demographic boxes. Just before the Hotel burns down in 2019, it becomes the subject of an amateur student film like The Blair Witch Project.

The Hotel is a fenland folly, built on the site of a pond where a suspected witch was drowned. Ever after, it is a cursed place. Those who build the hotel and stay in it are subject to violence, fear, and eruptions of the unexplained – especially if they go in Room 63. Anyone who visits once seems doomed to return. Most of the stories are in the first person, which makes sense for dramatic monologues. The speakers are guests, employees, and monsters. Some are BIPOC or queer, as if to tick off demographic boxes. Just before the Hotel burns down in 2019, it becomes the subject of an amateur student film like The Blair Witch Project. The first section, “When the Angel Comes for You,” is about the Virgin Mary, its 15 poems corresponding to the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary (as Padel explains in a note at the end; had she not, that would have gone over my head). The opening poem about the Annunciation is the most memorable its contemporary imagery emphasizing Mary’s youth and naivete: “a flood of real fear / and your heart / in the cowl-neck T-shirt from Primark / suddenly convulsed. But your old life // now seems dry as a stubbed / cigarette.” The third section, “Lady of the Labyrinth,” is about Ariadne, inspired by the snake goddess figurines in a museum on Crete. The message here is the same: “there is always the question of power / and girl is a trajectory / of learning how to deal with it”.

The first section, “When the Angel Comes for You,” is about the Virgin Mary, its 15 poems corresponding to the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary (as Padel explains in a note at the end; had she not, that would have gone over my head). The opening poem about the Annunciation is the most memorable its contemporary imagery emphasizing Mary’s youth and naivete: “a flood of real fear / and your heart / in the cowl-neck T-shirt from Primark / suddenly convulsed. But your old life // now seems dry as a stubbed / cigarette.” The third section, “Lady of the Labyrinth,” is about Ariadne, inspired by the snake goddess figurines in a museum on Crete. The message here is the same: “there is always the question of power / and girl is a trajectory / of learning how to deal with it”.

Hilary: Briefly, A Delicious Life by Nell Stevens (I’d second that one; here’s

Hilary: Briefly, A Delicious Life by Nell Stevens (I’d second that one; here’s

It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?!

It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?! My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.

My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen: This is top-notch scientific journalism: pacey, well-structured, and gripping. The best chapters are on Ebola and SARS; the SARS chapter, in particular, reads like a film screenplay, if this were a far superior version of Contagion. It’s a sobering subject, with some quite alarming anecdotes and statistics, but this is not scare-mongering for the sake of it; Quammen is frank about the fact that we’re still all more likely to get heart disease or be in a fatal car crash.

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen: This is top-notch scientific journalism: pacey, well-structured, and gripping. The best chapters are on Ebola and SARS; the SARS chapter, in particular, reads like a film screenplay, if this were a far superior version of Contagion. It’s a sobering subject, with some quite alarming anecdotes and statistics, but this is not scare-mongering for the sake of it; Quammen is frank about the fact that we’re still all more likely to get heart disease or be in a fatal car crash.

Infinite Home by Kathleen Alcott: “Edith is a widowed landlady who rents apartments in her Brooklyn brownstone to an unlikely collection of humans, all deeply in need of shelter.” (I haven’t read it, but I do have a copy; now would seem like the time to read it!)

Infinite Home by Kathleen Alcott: “Edith is a widowed landlady who rents apartments in her Brooklyn brownstone to an unlikely collection of humans, all deeply in need of shelter.” (I haven’t read it, but I do have a copy; now would seem like the time to read it!)

I love the sound of A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre: “Finding himself locked in his room for six weeks, a young officer journeys around his room in his imagination, using the various objects it contains as inspiration for a delightful parody of contemporary travel writing and an exercise in Sternean picaresque.”

I love the sound of A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre: “Finding himself locked in his room for six weeks, a young officer journeys around his room in his imagination, using the various objects it contains as inspiration for a delightful parody of contemporary travel writing and an exercise in Sternean picaresque.”

Sourdough by Robin Sloan: Lois Clary, a Bay Area robot programmer, becomes obsessed with baking. “I needed a more interesting life. I could start by learning something. I could start with the starter.” She attempts to link her job and her hobby by teaching a robot arm to knead the bread she makes for a farmer’s market. Madcap adventures ensue. It’s a funny and original novel and it makes you think, too – particularly about the extent to which we should allow technology to take over our food production.

Sourdough by Robin Sloan: Lois Clary, a Bay Area robot programmer, becomes obsessed with baking. “I needed a more interesting life. I could start by learning something. I could start with the starter.” She attempts to link her job and her hobby by teaching a robot arm to knead the bread she makes for a farmer’s market. Madcap adventures ensue. It’s a funny and original novel and it makes you think, too – particularly about the extent to which we should allow technology to take over our food production.

The Egg & I by Betty Macdonald: MacDonald and her husband started a rural Washington State chicken farm in the 1940s. Her account of her failure to become the perfect farm wife is hilarious. The voice reminded me of Doreen Tovey’s: mild exasperation at the drama caused by household animals, neighbors, and inanimate objects. “I really tried to like chickens. But I couldn’t get close to the hen either physically or spiritually, and by the end of the second spring I hated everything about the chicken but the egg.” Perfect pre-Easter reading.

The Egg & I by Betty Macdonald: MacDonald and her husband started a rural Washington State chicken farm in the 1940s. Her account of her failure to become the perfect farm wife is hilarious. The voice reminded me of Doreen Tovey’s: mild exasperation at the drama caused by household animals, neighbors, and inanimate objects. “I really tried to like chickens. But I couldn’t get close to the hen either physically or spiritually, and by the end of the second spring I hated everything about the chicken but the egg.” Perfect pre-Easter reading.

Anything by Bill Bryson

Anything by Bill Bryson

Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott

Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott