Book Triage

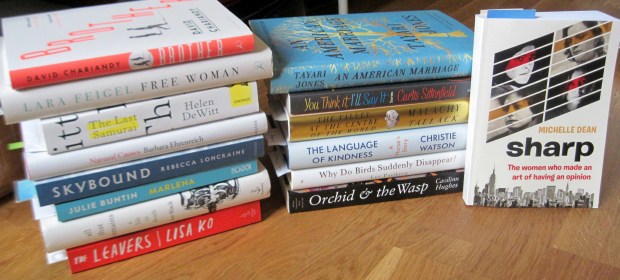

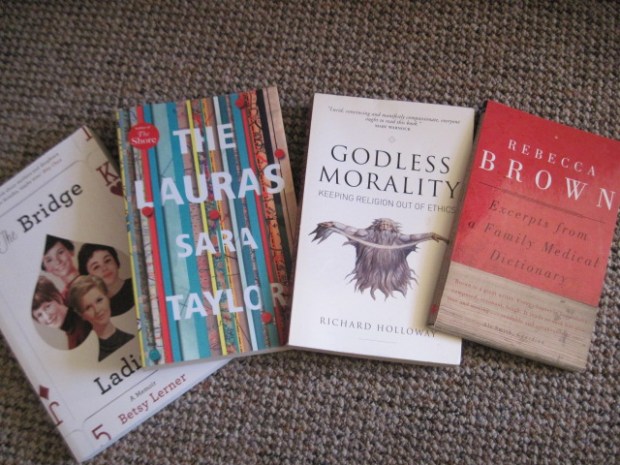

I feel like I have more books staring at me than ever before. I could blame free library reservations and a trip to Wigtown, but there’s one more major reason for the books stacking up: an utter lack of restraint when it comes to requesting or accepting books for review. I’ve had loads of books coming through the door in the past month or so. Some were offered to me by authors or publishers via Goodreads, Twitter or my blog’s contact form. Others I sent e-mails to request after I saw tempting reviews in the Guardian or previews on Susan’s blog.

Of course I want to read all of these books. I really want to read most of them. Otherwise I wouldn’t have gone to the trouble of requesting, borrowing or buying them. But even so, there’s only so much time. It’s not just a simple matter of picking up the book(s) from the stack that I most feel like reading at a given moment anymore. No, it’s become a triage process whereby I have to assess them by order of urgency.

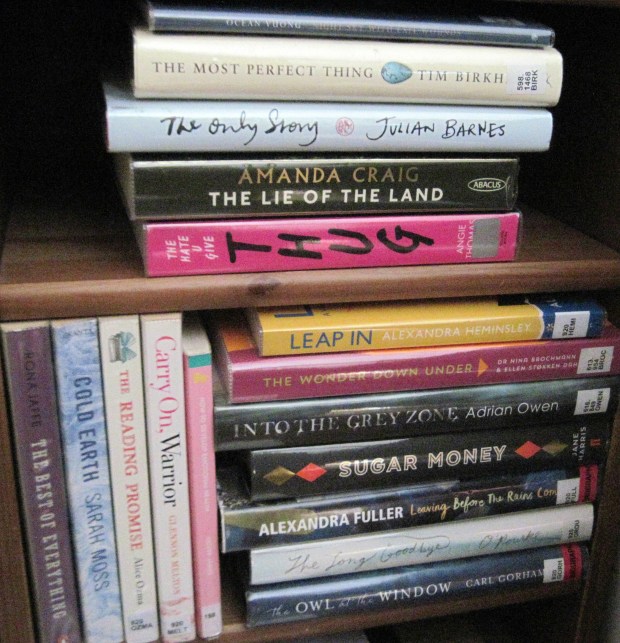

So, what are my priorities? Here’s a baker’s dozen, in photos.

- Wellcome Book Prize shortlist reading. I’m on the last of six now; this is for the blog tour coming up next week.

- Library books that are due in early May and requested after me.

- Books I’ve requested for a blog review, in release date order. I feel so behind that you can expect some doubled-up reviews or mini-reviews in roundup form.

- Books I’ve agreed to review for another outlet, even if that’s just Goodreads.

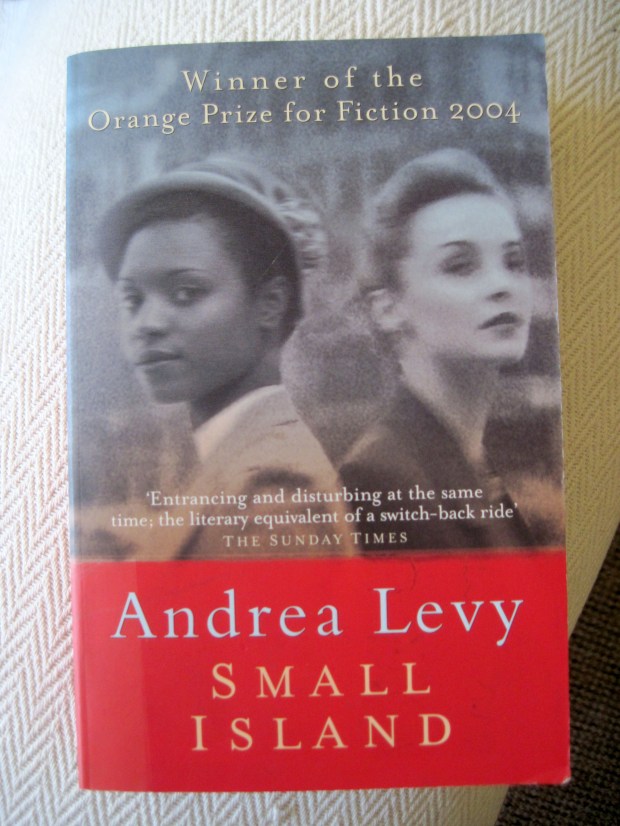

- My first-ever buddy read: Small Island with Buried in Print and Consumed by Ink, arranged months ago. Join us!

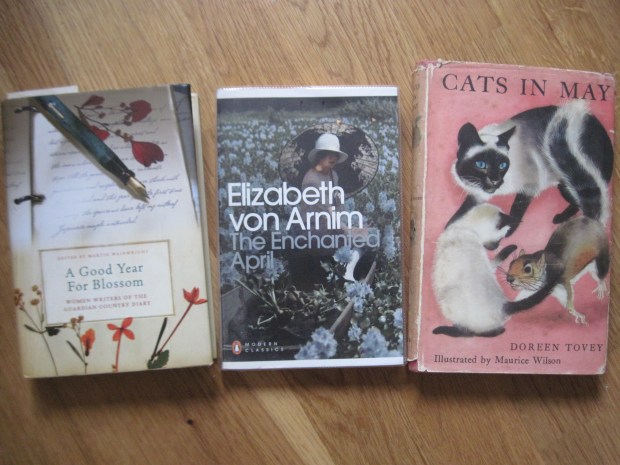

- Month- or season-specific reads.

- Public library books with no current renewal issues.

- Booker Prize winners for the 50th anniversary this summer – I’ll at least review the Coetzee for Shiny New Books, and perhaps a few more on the blog if I get the time.

- Three more Iris Murdoch novels to read as part of Liz’s #IMReadalong later on in the year, starting in June.

- Bibliotherapy prescriptions.

- Books I’ve set aside temporarily, generally because I have enthusiastically started too many at once and had to put some down to pick up more time-sensitive review books. Many of these I was enjoying very much and could see turning out to be 4- or even 5-star reads (especially Brooks, Frame and Matthiessen); others I might end up abandoning.

- University library books, which can be renewed pretty much indefinitely.

- Every other book I own, even if I had it eyed up for a particular challenge. My vague resolution to read lots of travel books and biographies has pretty much gone by the wayside so far. I also have barely managed a single classic. Sigh! There’s still two-thirds of the year left, but I certainly won’t be managing the one a month from these genres that I proposed.

What’s your book triage situation like?

Iris Murdoch Readalong: A Severed Head

A strange but very readable satire on who you’re supposed to love versus who you actually do. My sixth Murdoch novel, and a very good one for book clubs or for newcomers to start with, I think, given how much it tackles in its just over 200 pages.

Love Triangle

As in Under the Net, we have a male narrator; here it’s Martin Lynch-Gibbon, 41, a wine merchant’s son who’s writing a work of military history. He’s been married to Antonia, five years his senior, for 11 years now. Martin also has a mistress, 26-year-old Georgie Hands. The thrill of the illicit, of possessing both these appealing women, is too much to resist, but he has a sense of being on the cusp – his delicately balanced life is about to go up in flames.

Love Quadrilateral

Antonia gets home from her psychoanalysis appointment and appears to be acting strangely. She soon confesses to Martin that she’s madly in love with her therapist, Palmer Anderson, who is half-American and has been Martin’s friend for years. They amicably agree to part. Martin goes to talk with Palmer, who lays on the Freudian patter and convinces Martin that Antonia is more of a mother figure for him because of their age gap. It’s all very civilized.

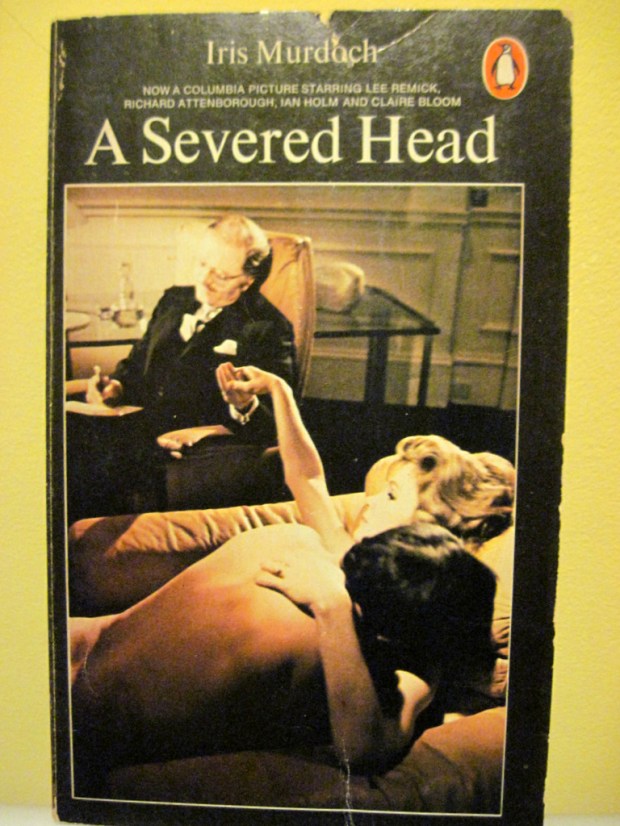

This awful cover image is a still from the 1970 film, presumably portraying Martin and Antonia in flagrante on Palmer’s therapy couch? Starring Lee Remick, Richard Attenborough and Ian Holm.

Love Hexagon?

We meet Martin’s brother Alexander and sister Rosemary when he goes to Rembers, the family estate in the Cotswolds, for the Christmas holidays. It seems Alexander’s always been somewhat in love with Antonia – he even sculpted her head. After lovely scenes of the snow seen from the train via Reading and a Christmas spent en famille, another player comes onto the scene: Palmer’s sister, Honor Klein, whom Martin picks up from Liverpool Street station. She’s cool and a bit domineering, and a dab hand with a samurai sword. Martin is smitten. But just wait until he goes to visit her in Cambridge…

As the members of this small group fall in and then out of love with each other, Murdoch explores any number of weighty ideas and themes. With a samurai sword around (as pictured on a couple of more recent Penguin covers), you have to wonder if, like Chekhov’s gun, it’s bound to be used in a violent way. At the very least it’s a phallic symbol, turning up in dreams along with blood, which itself is symbolized by the red wine so frequently consumed and sometimes spilled in the novel. I thought of the title as asking what happens when the mind and body become detached from each other and want different things. There are also plentiful references to ancient superstitions and taboos: the cuckold’s horns, the Oedipal impulse, and the rituals surrounding the oracular voice.

My back cover blurb. Sorry if you consider anything here a spoiler…

What with all the scenes of people bursting into a room and declaring their love for someone else now, and Martin moving his belongings back and forth, this is something like a comic play. It’s one of the few Murdoch novels to have been adapted for the theatre or cinema (it has also been a radio play), and you can see why: it has a theatrical, quick-moving story line, and Murdoch even deliberately references “actors in a play” and “the drama.” Martin’s sense of helplessness is also likened to feeling destined to play one role in life, whether he likes it or not. It’s a very visual novel, too, with objects (like the Audubon prints and the Meissen cockatoos decorating the Lynch-Gibbons’ place, or “we sat enlaced like a beautiful netsuke”) and colors taking on significance in a way that I’m sure must have influenced A.S. Byatt.

A couple of small things bothered me: the overkill in describing Honor’s features as Jewish, and the overall short shrift given to Georgie. But on the whole I really enjoyed this one, especially Martin’s three (increasingly informal and defensive) versions of the same apology letter, and the fact that Palmer almost always appears in his dressing gown. In one 2017 year-end recommendation for Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends, I saw it compared with A Severed Head, and I guess I can see why: the love quadrilateral, the blend of tragic and comic themes, and the perhaps recklessly optimistic ending. Both are well worth reading.

My favorite snippet of dialogue:

(Martin) “‘We’ve been happy. I want to go on being happy.’

‘Happy, yes,’ said Antonia. ‘But happiness is not the point. We aren’t getting anywhere. You know that as well as I do.’

‘One doesn’t have to get anywhere in a marriage. It’s not a public conveyance.’”

My rating:

I’m participating on and off in Liz Dexter’s two-year Iris Murdoch readalong project to get through some of the paperbacks I already own. See also her very interesting introductory post on A Severed Head. I have several more of the readalong books lined up for later in the year: The Italian Girl in June, The Nice and the Good in September, and An Accidental Man in December. Join us for one or more!

Have you read this or anything else by Iris Murdoch?

Classic of the Month: Under the Net (#IMReadalong)

I plan to dip in and out of Liz Dexter’s two-year Iris Murdoch readalong project to increase my familiarity with Murdoch and get through some of the paperbacks I happen to own. Even though I don’t own it, I decided to join in with Under the Net (1954) to see how her fiction career began. My university library copy is a rebound 1960s Penguin paperback, so – alas! – has a generic cover. See Liz’s introductory post for the different cover images and to get a peek at some of the recurring Murdochian themes that make their first appearance here.

Under the Net is narrated by Jake Donoghue, a translator who arrives back in London after a trip to France to find that he’s being kicked out of the flat where he’s been living for free with his friend Finn. In his desultory search for where to go next he takes readers along to Mrs Tinckham’s cat-filled shop, his Jewish philosopher friend Dave’s place, and the theatre where a former girlfriend, Anna Quentin, is in charge of props. (One of my favorite scenes has him accidentally locked into the theatre overnight; he has to sleep among the costumes.)

Anna’s sister Sadie, an actress, offers Jake a role as her bodyguard; she has a stalker of sorts, fireworks manufacturer and film studio owner Hugo Belfounder – whom, it turns out, Jake already knows. Together they were guinea pigs for an experiment on the common cold, and Jake secretly worked up Hugo’s conversations into a poorly received book called The Silencer. “Hugo was my destiny,” Jake muses; even though he’s embarrassed to see Hugo again, he gets drawn back into a connection with him.

One of the central themes of the novel, playing out with various characters, is the difficulty of seeing people clearly rather than resting with the image of them you’ve built up in your mind. I enjoyed Jake’s contrasting of physical and intellectual work, and his (sometimes contradictory) reflections on solitude and introversion:

I sometimes feel that Finn has very little inner life. I mean no disrespect to him in saying this; some have and some haven’t. I connect this too with his truthfulness. Subtle people, like myself, can see too much ever to give a straight answer.

I hate solitude, but I am afraid of intimacy. The substance of my life is a private conversation with myself which to turn into a dialogue would be equivalent to self-destruction. The company which I need is the company which a pub or a café will provide.

If like myself you are a connoisseur of solitude, I recommend to you the experience of being alone in Paris on the fourteenth of July.

Many readers probably expect Murdoch’s books to be dense and difficult, bogged down with philosophical ideas. But what I most noticed about this first novel is how humorous it is: it’s even madcap in places, with some coming and going via windows and Mister Mars, the film star dog, playing dead to get Jake out of a sticky situation. Over at Liz’s blog we’ve been discussing whether Murdoch is a typical ‘woman writer’; if her books had been published anonymously or under her initials, would it have been assumed that she was a man? I think so, given her success in creating a male narrator and her focus on the world of work and less traditional domestic arrangements.

This is my sixth Murdoch book. I didn’t enjoy Under the Net as much as the Booker Prize-winning The Sea, The Sea or The Bell ( ), but liked it more than The Black Prince and An Unofficial Rose (

), but liked it more than The Black Prince and An Unofficial Rose ( ) [I’ve also read one of her philosophy books, The Fire and the Sun (

) [I’ve also read one of her philosophy books, The Fire and the Sun ( ; I could make neither head nor tail of it)], so it falls in the middle for me so far at a solid

; I could make neither head nor tail of it)], so it falls in the middle for me so far at a solid  . I’m looking forward to participating with several more of the readalong books next year, starting with A Severed Head in March.

. I’m looking forward to participating with several more of the readalong books next year, starting with A Severed Head in March.

Another favorite line, spoken by Hugo: “One must just blunder on. Truth lies in blundering on.”

Have you read anything by Iris Murdoch? Do you enjoy her work?

Join us for one or more of the readalong books!

Jacob’s Room Is Full of Books by Susan Hill

Susan Hill has published dozens of books in multiple genres, but is probably best known for her perennially popular ghost story, The Woman in Black (1983). Apart from that and two suspense novellas, the only book I’d read by her before is Howards End Is on the Landing (2009), a sort of prequel to this work. Both are bookish memoirs animated by the specific challenge to spend more time reading from her shelves and revisiting the books that have meant the most to her in the past. Though not quite a journal, this is set up chronologically and also incorporates notes on the weather, family events and travels, and natural phenomena encountered near her home in Norfolk.

The Virginia Woolf reference in the title is fitting, as Hill realizes she has four shelves’ worth of books about Woolf and her Bloomsbury set. It’s just one of many mini-collections she discovers in her library on regular “de-stocking” drives when she tries to be realistic about what, at age 75, she’s likely to reread or reference in the future. “A book that cannot be returned to again and again, and still yield fresh entertainment and insights, is only half a book,” Hill contends. Some authors who merit frequent rereading for her are Edith Wharton, Muriel Spark, W. Somerset Maugham and Olivia Manning, while other passions had a time limit: she’s gone off E.F. Benson, and no longer reads about Antarctica or medieval theology.

Hill is unashamedly opinionated, though she at least has the humility to ask what individual taste matters. Her substantial list of no-nos includes fairy tales, science fiction, Ethan Frome, Patricia Highsmith and e-readers, and she seems strangely proud of never having read Jane Eyre. She’s ambivalent about literary festivals and especially about literary prizes: they were a boon to her as a young author, but she was also on the infamous 2011 Booker Prize judging panel, and disapproves of that prize being opened up to American entries.

Hill is unashamedly opinionated, though she at least has the humility to ask what individual taste matters. Her substantial list of no-nos includes fairy tales, science fiction, Ethan Frome, Patricia Highsmith and e-readers, and she seems strangely proud of never having read Jane Eyre. She’s ambivalent about literary festivals and especially about literary prizes: they were a boon to her as a young author, but she was also on the infamous 2011 Booker Prize judging panel, and disapproves of that prize being opened up to American entries.

As well as grumpy pronouncements, this book is full of what seems like name-dropping: encounters with Iris Murdoch, J.B. Priestley, Susan Sontag and the like. (To be fair, the stories about Murdoch and Sontag are rather lovely.) Although aspects of this book rubbed me the wrong way, I appreciated it as a meditation on how books are woven into our lives. I took note of quite a few books I want to look up, and Hill ponders intriguing questions that book clubs might like to think about: Can we ever enjoy books as purely as adults as we did as children, now that we have to “do something” with our reading (e.g. discussing or reviewing)? Is it a lesser achievement to turn one’s own life experiences into fiction than to imagine incidents out of thin air? Will an author unconsciously “catch the style” of any writer they are reading at the time of their own compositions? Is it better to come to a book blind, without having read the blurb or anything else about it?

You’ll applaud; you’ll be tempted to throw the book at the wall (this was me with the early page disparaging May Sarton). Perhaps on consecutive pages. But you certainly won’t be indifferent. And a book that provokes a reaction is a fine thing.

Some favorite lines:

“Cold room, warm bed, good book.”

“I have had fifty-five years of experience but still every book is like walking a tightrope. I might fall off.”

“People say they can never part with a book. I can. As fast as I get one out of the back door, two new ones come in through the front anyway.”

“How many people are there living in the books here? Only take the complete novels of Dickens and add up all the characters in each one and then multiply by … and I already need to lie down. Overall, there must be thousands of imaginary people sharing this house with us.”

“One of the best presents anyone can give you is the name of a writer whose books they believe will be ‘you’ – and they are. Someone you would almost certainly never have found for yourself.”

My rating:

Jacob’s Room Is Full of Books was released in the UK on October 5th. My thanks to Profile Books for the free copy for review.

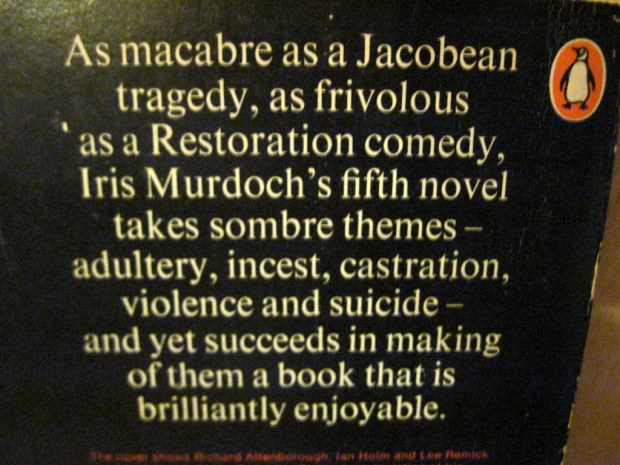

As a God Might Be by Neil Griffiths

[Note: A shortened, edited version of this review appeared in the June 15th, 2018 issue of the Church Times.]

Proctor McCullough isn’t a churchgoer. He’s not even particularly religious. Yet somehow he senses that God is calling him to build a chapel, with a little house beside it, on a cliff in the southwest of England. It’s a source of bewilderment for his partner, Holly, and their London friends. Is Mac mentally ill, or having a particularly acute midlife crisis? He’s handed off from a minister to a therapist to a neurologist, but no one knows what to make of him. This forty-four-year-old father of two, an otherwise entirely rational-seeming advisor to the government on disaster situations, won’t be deterred from his mission.

It’s important to get a sense of the way this character speaks:

I want a structure that will move people to contemplate something other than all the obvious stuff … to be confronted with a sense of something and only be able to define it as Other.

God is the transcendent Other for whom creation, what we know as life, is a gratuitous act of love, a dispossession of a portion of His infinite creativity given over to our thriving. It is a gift from His infinite excess. That we can know Him at all is because of the possibility of this excess within us, which we experience as love, art, great feats of the mind. Our bounty is Him.

Down at the project site, Mac acquires four young workers/disciples: Rebecca, Nathaniel, Terry and Rich. Rebecca is a sarcastic, voluptuous teenager who will be off to Cambridge in a few months. She perhaps represents vanity, temptation and judgment, while the other three are more difficult to slot into symbolic roles. Terry is a dreadlocked lager lout who takes care of a mother with early dementia; contrary to appearances, he’s also a thinker, and takes to carrying around a Bible along with a collection of other theological works. Nat and Rich are more sketch-like figures, just ciphers really, which became problematic for me later on.

With Mac we shuttle between the building site and his home in London for weeks at a time. The idea of incorporating Pascal’s mystical hexagon into the church design captivates him, and the costs – initially set at £100,000 – balloon. Meanwhile, his relationship with Holly is strained almost to the breaking point as they each turn to alternative confidants, and there’s a renegotiation process as they decide whether their actions have torn them apart for good.

With Mac we shuttle between the building site and his home in London for weeks at a time. The idea of incorporating Pascal’s mystical hexagon into the church design captivates him, and the costs – initially set at £100,000 – balloon. Meanwhile, his relationship with Holly is strained almost to the breaking point as they each turn to alternative confidants, and there’s a renegotiation process as they decide whether their actions have torn them apart for good.

Like Sarah Moss, Neil Griffiths realistically blends serious concepts with everyday domestic tasks: sure, there may be a God-ordained chapel to build, but Mac also has to do the shopping and get his six-year-old twins fed and in bed at a decent hour. If Mac is meant to be a Messiah figure here, he’s a deeply flawed one; he can even be insufferable, especially when delivering his monologues on religion. If you’re like me, you’ll occasionally get incensed with him – particularly when, at the midpoint, he concocts a Clintonian justification for his behavior.

All the same, the themes and central characters were strong enough to keep me powering through this 600-page novel of ideas. Mac’s violent encounters with God and with the nature of evil are compelling, and although some of the events of the last third push the boundaries of credibility, it’s worth sticking with it to see where Griffiths takes the plot. There’s no getting past the fact that this is a dense theological treatise, but overlaid on it is a very human story of incidental families and how love sustains us through the unbearable.

If I had to point to the novel’s forebears, I’d mention Hamlet, A.S. Byatt’s The Virgin in the Garden, Michael Arditti’s Easter, and even Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. If you’ve read any Dostoevsky (I haven’t, yet) or Iris Murdoch, you’ll likely spot philosophical echoes. The title itself is from Wallace Stevens. It’s all unabashedly highbrow, and a greater than average familiarity with the Christian tradition is probably key. For the wary, I’d suggest not trying too hard to read metaphorical significance into character names or chapter and section titles – I’m sure those meanings are in there, but better to let the story carry you along rather than waste time trying to work it all out.

While reading this novel I was bitterly regretting the demise of Third Way magazine; it would have been a perfect place for me to engage with Griffiths’ envelope-pushing theology. I was also wishing I was still involved with Greenbelt Festival’s literature programming, as this would make a perfect Big Read. (Though however would we get people to read 600 pages?! In my experience of book clubs, it’s hard enough to get them to read 200.)

I’m grateful to Dodo Ink (“an independent UK publisher publishing daring and difficult fiction”) for stepping into the breach and taking a chance on a book that will divide Christians and the nonreligious alike, and to publicist Nicci Praça for the surprise copy that turned up on my doorstep. This turned out to be just my sort of book: big and brazen, a deep well of thought that will only give up its deeper meanings upon discussion and repeat readings.

My rating:

As a God Might Be was published in the UK by Dodo Ink on October 26th. This is Neil Griffiths’ third novel, after Betrayal in Naples (2004) and Saving Caravaggio (2006). He says that this most recent book took him seven years to write.

Six “Love” Books for Valentine’s Day

Starting in mid-January I began surveying my shelves, library stack and Kindle for books with “love” in the title. Here are the six I had time to try; I didn’t get to Alain de Botton’s The Course of Love on my Kindle, nor my paperback copies of Iris Murdoch’s The Sacred and Profane Love Machine and Nancy Horan’s Loving Frank.

You’ll notice that a number of the books I’ve read aren’t that optimistic about love; in several cases the use of the word in the title even seems to be ironic. As Lady Montdore exclaims in Love in a Cold Climate, “Love indeed – whoever invented love ought to be shot.” So I can’t offer them as particularly romantic choices. But let’s start positively, with some pleasantly out-of-the-ordinary love poems.

From Me to You: Love Poems, U.A. Fanthorpe and R.V. Bailey

Ursula Fanthorpe and Rosie Bailey met as English teachers at the same Cheltenham school in their late twenties and were partners for nearly 40 years. None of the poems in this short volume are attributed, though I recognized a few from Fanthorpe’s Collected Poems. They’re not particularly distinguished as poetry, but I appreciated the simple, unsentimental examples of what makes up everyday life with a partner: “There is a kind of love called maintenance, / Which stores the WD40 and knows when to use it; // Which checks the insurance, and doesn’t forget / The milkman” (“Atlas”) and “I’m working on a meal you haven’t had to imagine, / A house cleaned to the rafters” (“Dear Valentine”). [Public library]

Ursula Fanthorpe and Rosie Bailey met as English teachers at the same Cheltenham school in their late twenties and were partners for nearly 40 years. None of the poems in this short volume are attributed, though I recognized a few from Fanthorpe’s Collected Poems. They’re not particularly distinguished as poetry, but I appreciated the simple, unsentimental examples of what makes up everyday life with a partner: “There is a kind of love called maintenance, / Which stores the WD40 and knows when to use it; // Which checks the insurance, and doesn’t forget / The milkman” (“Atlas”) and “I’m working on a meal you haven’t had to imagine, / A house cleaned to the rafters” (“Dear Valentine”). [Public library]

What I Loved, Siri Hustvedt

This 2003 novel could just as well have been titled “What I Lost,” which might be truer to its elegiac tone. Narrated by Professor Leo Hertzberg and set between the 1970s and 1990s, it’s about two New York City couples – academics and artists – and the losses they suffer over the years. With themes of modern art, perspective, memory, separation and varieties of mental illness, it asks to what extent we can ever know other people or use replacements to fill the gaps left by who and what is missing. Read it if you’ve enjoyed The Suicide of Claire Bishop by Carmiel Banasky, other books by Siri Hustvedt, or anything by Howard Norman. My favorite lines about love were “I often thought of our marriage as one long conversation” and “love thrives on a certain kind of distance … it requires an awed separateness to continue.” [Charity shop]

This 2003 novel could just as well have been titled “What I Lost,” which might be truer to its elegiac tone. Narrated by Professor Leo Hertzberg and set between the 1970s and 1990s, it’s about two New York City couples – academics and artists – and the losses they suffer over the years. With themes of modern art, perspective, memory, separation and varieties of mental illness, it asks to what extent we can ever know other people or use replacements to fill the gaps left by who and what is missing. Read it if you’ve enjoyed The Suicide of Claire Bishop by Carmiel Banasky, other books by Siri Hustvedt, or anything by Howard Norman. My favorite lines about love were “I often thought of our marriage as one long conversation” and “love thrives on a certain kind of distance … it requires an awed separateness to continue.” [Charity shop]

Love in a Cold Climate, Nancy Mitford

I didn’t realize this 1949 novel is a sequel to The Pursuit of Love, so it took a while to figure out who all the characters were. Fanny Logan is a cousin orbiting around Lord and Lady Montdore and their daughter Polly Hampton, all recently returned from some years in India. Fanny marries an Oxford don, while Polly shocks everyone by eloping with her uncle by marriage, “Boy” Dougdale, a recent widower once known as the “Lecherous Lecturer” for interfering with little girls. (This hint of pedophilia is carelessly tossed off in a way no writer would get away with today.) Meanwhile, the heir to the Hampton estate, an effeminate chap named Cedric, comes over from Canada for a visit and wins Lady Montdore over. This amusing picture of aristocratic life in the 1930s marvels at who we love and why. [Bookbarn International]

I didn’t realize this 1949 novel is a sequel to The Pursuit of Love, so it took a while to figure out who all the characters were. Fanny Logan is a cousin orbiting around Lord and Lady Montdore and their daughter Polly Hampton, all recently returned from some years in India. Fanny marries an Oxford don, while Polly shocks everyone by eloping with her uncle by marriage, “Boy” Dougdale, a recent widower once known as the “Lecherous Lecturer” for interfering with little girls. (This hint of pedophilia is carelessly tossed off in a way no writer would get away with today.) Meanwhile, the heir to the Hampton estate, an effeminate chap named Cedric, comes over from Canada for a visit and wins Lady Montdore over. This amusing picture of aristocratic life in the 1930s marvels at who we love and why. [Bookbarn International]

Enduring Love, Ian McEwan

Interesting to consider this as a precursor to Saturday: both have a scientist as the protagonist and get progressively darker through a slightly contrived stalker plot. Enduring Love opens, famously, with a ballooning accident that leaves its witnesses questioning whether they couldn’t have done more to prevent it. Freelance science journalist Joe Rose – on a picnic with his partner, Keats scholar Clarissa, at the time – was one of those who rushed to help, as was Jed Parry, a young Christian zealot who fixates on Joe. He seems to think that by loving Joe, a committed atheist, he can bring him to God. In turn, Joe’s obsession with Jed’s harassment campaign drives Clarissa away. It’s a deliciously creepy read that contrasts rationality with religion and inquires into what types of love are built to last. [Charity shop]

Interesting to consider this as a precursor to Saturday: both have a scientist as the protagonist and get progressively darker through a slightly contrived stalker plot. Enduring Love opens, famously, with a ballooning accident that leaves its witnesses questioning whether they couldn’t have done more to prevent it. Freelance science journalist Joe Rose – on a picnic with his partner, Keats scholar Clarissa, at the time – was one of those who rushed to help, as was Jed Parry, a young Christian zealot who fixates on Joe. He seems to think that by loving Joe, a committed atheist, he can bring him to God. In turn, Joe’s obsession with Jed’s harassment campaign drives Clarissa away. It’s a deliciously creepy read that contrasts rationality with religion and inquires into what types of love are built to last. [Charity shop]

An Exclusive Love: A Memoir, Johanna Adorján

The author’s grandparents, Hungarian Holocaust survivors who moved to Denmark as refugees, committed suicide together on October 13, 1991. Her grandfather, an orthopedic surgeon who had been in an Austrian concentration camp, was terminally ill and his wife was determined not to live a day without him. This short, elegant memoir alternates Adorján’s imagined reconstruction of her grandparents’ last day with an account of their life together, drawn from family memories and interviews with those who knew them. She wonders whether, like Primo Levi and Arthur Koestler, theirs was a typically Jewish failure to fit in wherever they went, and/or a particularly Hungarian melancholy. “The answer is their great love,” the newspaper report of their death insisted. [Waterstones clearance]

The author’s grandparents, Hungarian Holocaust survivors who moved to Denmark as refugees, committed suicide together on October 13, 1991. Her grandfather, an orthopedic surgeon who had been in an Austrian concentration camp, was terminally ill and his wife was determined not to live a day without him. This short, elegant memoir alternates Adorján’s imagined reconstruction of her grandparents’ last day with an account of their life together, drawn from family memories and interviews with those who knew them. She wonders whether, like Primo Levi and Arthur Koestler, theirs was a typically Jewish failure to fit in wherever they went, and/or a particularly Hungarian melancholy. “The answer is their great love,” the newspaper report of their death insisted. [Waterstones clearance]

Note: That striking cover is by Leanne Shapton.

And another nonfiction selection that I didn’t make it all the way through:

A Book about Love, Jonah Lehrer

(Abandoned at 31%.) Although I can see why he starts where he does, Lehrer’s early focus on attachment and attunement – two psychological theories of how babies learn to relate affectionately to others – means the book gets bogged down in studies performed on mice and/or children and feels more like a parenting book than anything else. (If that’s what you’re after, read All Joy and No Fun.) A glance at the table of contents suggests the rest of the book will go into marriage, divorce and how love changes over time, but I couldn’t be bothered to stick around. That said, Lehrer’s popular science writing is clear and engaging, and with the heartfelt mea culpa at the start of this book I couldn’t hold a grudge about his earlier plagiarism scandal. [Kindle book from NetGalley.]

(Abandoned at 31%.) Although I can see why he starts where he does, Lehrer’s early focus on attachment and attunement – two psychological theories of how babies learn to relate affectionately to others – means the book gets bogged down in studies performed on mice and/or children and feels more like a parenting book than anything else. (If that’s what you’re after, read All Joy and No Fun.) A glance at the table of contents suggests the rest of the book will go into marriage, divorce and how love changes over time, but I couldn’t be bothered to stick around. That said, Lehrer’s popular science writing is clear and engaging, and with the heartfelt mea culpa at the start of this book I couldn’t hold a grudge about his earlier plagiarism scandal. [Kindle book from NetGalley.]

No overtly heartwarming love stories in that selection, then, but are there any you fancy reading anyway? Have you read any “love” titles recently?

See also: The Guardian’s list of Top 10 Authentic Romances.

Birthday Happenings

One of the best things about being a home-based freelancer is that I can arrange my work schedule to suit my life. Having my birthday fall on a Friday this year was especially good because it meant I got until Monday to submit my daily editing load. My husband was working as usual, so I spent much of the day reading under the cat and charity shopping. I bought seven books, a nice mixture of England-themed nonfiction and juicy novels, plus new-to-me comfy black flats. (Total spend: £10.25.) Being short on time that evening, we lazily ordered delivery pizza for probably the first time in eight years, followed by cocktails and cake.

I didn’t end up using my literary cakes and cocktails books this year, but that gives me a chance to proffer my own pun names for what we did make. We tried two gin cocktails we’d found recipes for in the Guardian. The one they called “Elderflower Collins” was absolutely delicious: lemon juice, elderflower cordial and gin, topped up with San Pellegrino Limonata (lemon soda) and garnished with a lemon slice and a mint sprig. I dub it “A Visit from Mr. Collins,” as in the Bennet girls will have to down quite a few of these before…

I didn’t end up using my literary cakes and cocktails books this year, but that gives me a chance to proffer my own pun names for what we did make. We tried two gin cocktails we’d found recipes for in the Guardian. The one they called “Elderflower Collins” was absolutely delicious: lemon juice, elderflower cordial and gin, topped up with San Pellegrino Limonata (lemon soda) and garnished with a lemon slice and a mint sprig. I dub it “A Visit from Mr. Collins,” as in the Bennet girls will have to down quite a few of these before…

Unfortunately, the second cocktail was not a hit. The “Miss Polly Hawkins” combines chamomile-flavored gin (I steeped two chamomile teabags in 60 mL of gin for a week), rose syrup (we didn’t have it or want to buy it so substituted our homemade rosehip syrup), plain gin and egg white. Egg white is a fairly frequent ingredient in cocktails – it adds gloss and body – but we found that it made the drink gloopy. That plus the overall floral and medicinal notes meant this was fairly hard to swallow; we had to drown it in sparkling water and ice cubes to get it down. Alas, I modify Iris Murdoch to call this “An Unappealing Rose.”

However, my cake was an unqualified success. I usually go for chocolate or chocolate/peanut butter desserts, but decided to be different this year and requested the Italian Pear and Ginger Cheesecake from Genevieve Taylor’s cookbook A Good Egg. It was sophisticated and delicious. Running with the Italy thing, I’ll pick out a Forster title and call it “Where Angels Pear to Tread.” (It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense; then again, neither do a lot of the names in Tequila Mockingbird and Scone with the Wind!)

However, my cake was an unqualified success. I usually go for chocolate or chocolate/peanut butter desserts, but decided to be different this year and requested the Italian Pear and Ginger Cheesecake from Genevieve Taylor’s cookbook A Good Egg. It was sophisticated and delicious. Running with the Italy thing, I’ll pick out a Forster title and call it “Where Angels Pear to Tread.” (It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense; then again, neither do a lot of the names in Tequila Mockingbird and Scone with the Wind!)

On Sunday the birthday fun continued with a trip to Hungerford Bookshop (our nearest independent bookshop) and a gentle country walk. I bought two secondhand books but came away with a total of four – in the basement they have a table covered in free proof copies, so my husband and I grabbed one each (how I wish I could have taken the lot!). It’s a great idea for rewarding customer loyalty and dealing with unwanted proofs; perhaps I’ll donate a stack of mine to them next time I’m there.

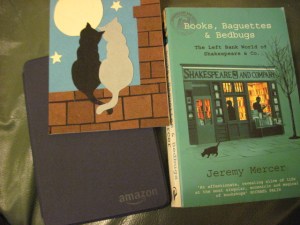

Two proofs (left) and two nonfiction purchases.

This year I got a Kindle case and two bookshop-themed memoirs as presents: The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap by Wendy Welch and Books, Baguettes and Bedbugs by Jeremy Mercer. I started reading the former – the story of a married couple opening a bookshop in recession-era Virginia – right away. I also got a poster frame so I can finally hang my literary map of the British Isles on the wall above my desk, and a “Shhhh, reading in progress” mug.

Consuming tasty food and drink + acquiring a baker’s dozen of books + getting out into the countryside = a great birthday weekend!

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This isn’t a happy family story. It’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate. Yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right, and it’s pulsing with emotion. One theme is how there can be different interpretations of the same events even within a small family. The novel is particularly strong on atmosphere, reminding me of Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea and Diane Setterfield’s The Thirteenth Tale. Fuller also manages her complex structure very well.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This isn’t a happy family story. It’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate. Yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right, and it’s pulsing with emotion. One theme is how there can be different interpretations of the same events even within a small family. The novel is particularly strong on atmosphere, reminding me of Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea and Diane Setterfield’s The Thirteenth Tale. Fuller also manages her complex structure very well.