Book Serendipity, Late 2020 into 2021

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (20+), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents than some. I also list some of my occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. The following are in chronological order.

- The Orkney Islands were the setting for Close to Where the Heart Gives Out by Malcolm Alexander, which I read last year. They showed up, in one chapter or occasional mentions, in The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange and The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields, plus I read a book of Christmas-themed short stories (some set on Orkney) by George Mackay Brown, the best-known Orkney author. Gavin Francis (author of Intensive Care) also does occasional work as a GP on Orkney.

- The movie Jaws is mentioned in Mr. Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe and Landfill by Tim Dee.

- The Sámi people of the far north of Norway feature in Fifty Words for Snow by Nancy Campbell and The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave.

- Twins appear in Mr. Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe and Tennis Lessons by Susannah Dickey. In Vesper Flights Helen Macdonald mentions that she had a twin who died at birth, as does a character in Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce. A character in The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard is delivered of twins, but one is stillborn. From Wrestling the Angel by Michael King I learned that Janet Frame also had a twin who died in utero.

- Fennel seeds are baked into bread in The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave and The Strays of Paris by Jane Smiley. Later, “fennel rolls” (but I don’t know if that’s the seed or the vegetable) are served in Monogamy by Sue Miller.

- A mistress can’t attend her lover’s funeral in Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan and Tennis Lessons by Susannah Dickey.

- A sudden storm drowns fishermen in a tale from Christmas Stories by George Mackay Brown and The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave.

Silver Spring, Maryland (where I lived until age 9) is mentioned in one story from To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss and is also where Peggy Seeger grew up, as recounted in her memoir First Time Ever. Then it got briefly mentioned, as the site of the Institute of Behavioral Research, in Livewired by David Eagleman.

Silver Spring, Maryland (where I lived until age 9) is mentioned in one story from To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss and is also where Peggy Seeger grew up, as recounted in her memoir First Time Ever. Then it got briefly mentioned, as the site of the Institute of Behavioral Research, in Livewired by David Eagleman.

- Lamb is served with beans at a dinner party in Monogamy by Sue Miller and Larry’s Party by Carol Shields.

- Trips to Madagascar in Landfill by Tim Dee and Lightning Flowers by Katherine E. Standefer.

Hospital volunteering in My Year with Eleanor by Noelle Hancock and Leonard and Hungry Paul by Ronan Hession.

Hospital volunteering in My Year with Eleanor by Noelle Hancock and Leonard and Hungry Paul by Ronan Hession.

- A Ronan is the subject of Emily Rapp’s memoir The Still Point of the Turning World and the author of Leonard and Hungry Paul (Hession).

- The Magic Mountain (by Thomas Mann) is discussed in Scattered Limbs by Iain Bamforth, The Still Point of the Turning World by Emily Rapp, and Snow by Marcus Sedgwick.

- Frankenstein is mentioned in The Biographer’s Tale by A.S. Byatt, The Still Point of the Turning World by Emily Rapp, and Snow by Marcus Sedgwick.

- Rheumatic fever and missing school to avoid heart strain in Foreign Correspondence by Geraldine Brooks and Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller. Janet Frame also had rheumatic fever as a child, as I discovered in her biography.

- Reading two novels whose titles come from The Tempest quotes at the same time: Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame and This Thing of Darkness by Harry Thompson.

- A character in Embers by Sándor Márai is nicknamed Nini, which was also Janet Frame’s nickname in childhood (per Wrestling the Angel by Michael King).

- A character loses their teeth and has them replaced by dentures in America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo and The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard.

Also, the latest cover trend I’ve noticed: layers of monochrome upturned faces. Several examples from this year and last. Abstract faces in general seem to be a thing.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Continuing the Story: Why I’m Wary of Sequels and Series, with Some Exceptions

Most of the time, if I learn that a book has a sequel or is the first in a series, my automatic reaction is to groan. Why can’t a story just have a tidy ending? Why does it need to sprawl further, creating a sense of obligation in its readers? Further adventures with The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window? Returning to the world of The Handmaid’s Tale? No, thank you.

It was different when I was a kid. I couldn’t get enough of series: the Little House on the Prairie books, Encyclopedia Brown, Nancy Drew, the Saddle Club, Redwall, the Baby-Sitters Club, various dragon series, Lilian Jackson Braun’s Cat Who mysteries, the Anne of Green Gables books… You name it, I read it. I think children, especially, gravitate towards series because they’re guaranteed more of what they know they like. It’s a dependable mold. These days, though, I’m famous for trying one or two books from a series and leaving the rest unfinished (Harry Potter: 1.5 books; Discworld: 2 books at random; Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files: 1 book; the first book of crime series by M.J. Carter, Judith Flanders and William Shaw).

But, like any reader, I break my own rules all the time – even if I sometimes come to regret it. I recently finished reading a sequel and I’m now halfway through another. I’ve even read a few high-profile sci fi/fantasy trilogies over the last eight years, even though with all of them I liked each sequel less than the book that went before (Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam books, Chris Beckett’s Dark Eden series and Deborah Harkness’s All Souls Trilogy).

A later book in a series can go either way for me – surpass the original, or fail to live up to it. Nonfiction sequels seem more reliable than fiction ones, though: if I discover that a memoirist has written a follow-up volume, I will generally rush to read it.

So, what would induce me to pick up a sequel?

I want to know what happens next.

WINNERS:

After reading Ruth Picardie’s Before I Say Goodbye, I was eager to hear from her bereaved sister, Justine Picardie. Ruth died of breast cancer in 1997; Justine writes a journal covering 2000 to 2001, asking herself whether death is really the end and if there is any possibility of communicating with her sister and other loved ones she’s recently lost. If the Spirit Moves You: Life and Love after Death is desperately sad, but also compelling.

Graeme Simsion’s Rosie series has a wonderfully quirky narrator. When we first meet him, Don Tillman is a 39-year-old Melbourne genetics professor who’s decided it’s time to find a wife. Book 2 has him and Rosie expecting a baby in New York City. I’m halfway through Book 3, in which in their son is 11 and they’re back in Australia. Though not as enjoyable as the first, it’s still a funny look through the eyes of someone on the autistic spectrum.

Graeme Simsion’s Rosie series has a wonderfully quirky narrator. When we first meet him, Don Tillman is a 39-year-old Melbourne genetics professor who’s decided it’s time to find a wife. Book 2 has him and Rosie expecting a baby in New York City. I’m halfway through Book 3, in which in their son is 11 and they’re back in Australia. Though not as enjoyable as the first, it’s still a funny look through the eyes of someone on the autistic spectrum.

Edward St. Aubyn’s Never Mind, the first Patrick Melrose book, left a nasty aftertaste, but I was glad I tried again with Bad News, a blackly comic two days in the life of a drug addict.

LOSERS:

Joan Anderson’s two sequels to A Year by the Sea are less engaging, and her books have too much overlap with each other.

Perhaps inevitably, Bill Clegg’s Ninety Days, about getting clean, feels subdued compared to his flashy account of the heights of his drug addiction, Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man.

Patrick Leigh Fermor’s Between the Woods and the Water was an awfully wordy slog compared to A Time of Gifts.

Patrick Leigh Fermor’s Between the Woods and the Water was an awfully wordy slog compared to A Time of Gifts.

Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow was one of my favorite backlist reads last year. I only read the first 60 pages of Children of God, though. It was a recent DNF after leaving it languishing on my pile for many months. While I was, of course, intrigued to learn that (SPOILER) a character we thought had died is still alive, and it was nice to see broken priest Emilio Sandoz getting a chance at happiness back on Earth, I couldn’t get interested in the political machinations of the alien races. Without the quest setup and terrific ensemble cast of the first book, this didn’t grab me.

I want to spend more time with these characters.

WINNERS:

Simon Armitage’s travel narrative Walking Away is even funnier than Walking Home.

I’m as leery of child narrators as I am of sequels, yet I read all 10 Flavia de Luce novels by Alan Bradley: quaint mysteries set in 1950s England and starring an eleven-year-old who performs madcap chemistry experiments and solves small-town murders. The Dead in Their Vaulted Arches (#6) was the best, followed by Thrice the Brinded Cat Hath Mew’d (#8).

I’m as leery of child narrators as I am of sequels, yet I read all 10 Flavia de Luce novels by Alan Bradley: quaint mysteries set in 1950s England and starring an eleven-year-old who performs madcap chemistry experiments and solves small-town murders. The Dead in Their Vaulted Arches (#6) was the best, followed by Thrice the Brinded Cat Hath Mew’d (#8).

Roald Dahl’s Going Solo is almost as good as Boy.

Alexandra Fuller’s Leaving Before the Rains Come is even better than Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight.

Likewise, Sarah Moss’s Signs for Lost Children, about a female doctor in the 1880s, is even better than Bodies of Light.

Doreen Tovey’s Cats in May is just as good as Cats in the Belfry.

LOSERS:

H. E. Bates’s A Breath of French Air revisits the Larkins, the indomitably cheery hedonists introduced in The Darling Buds of May, as they spend a month abroad in the late 1950s. France shows off its worst weather and mostly inedible cuisine; even the booze is barely tolerable. Like a lot of comedy, this feels slightly dated, and maybe also a touch xenophobic.

The first Hendrik Groen diary, about an octogenarian and his Old-But-Not-Dead club of Amsterdam nursing home buddies, was a joy, but the sequel felt like it would never end.

The first Hendrik Groen diary, about an octogenarian and his Old-But-Not-Dead club of Amsterdam nursing home buddies, was a joy, but the sequel felt like it would never end.

I loved Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead; I didn’t need the two subsequent books.

The Shakespeare Requirement, Julie Schumacher’s sequel to Dear Committee Members, a hilarious epistolary novel about an English professor on a Midwest college campus, was only mildly amusing; I didn’t even get halfway through it.

I finished Jane Smiley’s Last Hundred Years trilogy because I felt invested in the central family, but as with the SFF series above, the later books, especially the third one, were a letdown.

What next? I’m still unsure about whether to try the other H. E. Bates and Edward St. Aubyn sequels. I’m thinking yes to Melrose but no to the Larkins. Olive Kitteridge, which I’ve been slowly working my way through, is so good that I might make yet another exception and seek out Olive, Again in the autumn.

Sequels: yea or nay?

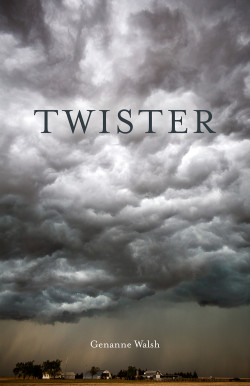

20 Books of Summer #15: Twister by Genanne Walsh

As the members of a small Midwestern town go about their daily business, it’s impossible to forget that a tornado is on its way. We begin with Rose, an ornery woman who, especially after the death of her soldier son Lance shook the town, has kept herself to herself. Perry Brown repeatedly proposes buying her farm so that he can expand his own operation, but she spurns all offers. Estranged from her stepsister Stella, Rose only has her dog Fergus for company. Short meteorological and historical overviews serve as tense interludes, moving from the general to the particular and providing brief transitions between character portraits.

As the members of a small Midwestern town go about their daily business, it’s impossible to forget that a tornado is on its way. We begin with Rose, an ornery woman who, especially after the death of her soldier son Lance shook the town, has kept herself to herself. Perry Brown repeatedly proposes buying her farm so that he can expand his own operation, but she spurns all offers. Estranged from her stepsister Stella, Rose only has her dog Fergus for company. Short meteorological and historical overviews serve as tense interludes, moving from the general to the particular and providing brief transitions between character portraits.

The successive chapters are simultaneous, interlocking stories that all take place in the immediate run-up to the storm touching down. We meet Scottie Dunleavy, an odd fellow who runs a shoe repair shop and leaves secret messages on the soles of people’s footwear. From Louise Logan, a gossipy bank teller, we learn how Rose and Stella fell out; through the eyes of Perry’s wife Nina we see just how tenuous Rose’s solitary existence has become.

After cycling through the perspectives of eight main characters, the book returns to the past in Part II, which starts with the meeting and marriage of Stella’s mother and Rose’s father and moves forward to the near present. The chapters turn choppier as the news of Lance’s death approaches. “Everyone shrank” after the loss of this hometown boy, Walsh writes; like the tornado, his death is an inescapable reality the narrative keeps moving towards.

I love small-town tales where you get to know all the neighbors and their secrets. Twister called to mind for me works by Jane Smiley and Anne Tyler, with Rose also somewhat reminiscent of Hagar in Margaret Laurence’s The Stone Angel. Casualties by Elizabeth Marro is another readalike, focusing on a bereaved mother and her soldier son’s backstory.

Twister was a novel I read slowly, just 10 or 15 pages at a sitting, to savor Walsh’s prose. It’s not a book to race through for the plot but one to linger over as you appreciate the delicacy of the characterization and the electric descriptions of the impending storm:

“If all warnings fail, here is what to look for: the sky turns green, greenish black, brackish. Hail falls. There is a sound that some liken to a freight train, a jet engine, a thousand souped-up Buicks drag racing across a sky. Debris falls from on high—frogs, playing cards, plywood, mud, rock.”

“Warm air rushes ecstatic through the center, pulling and turning, forcing cold air out and down in waves, feeding the dance. Cold coils, pulling inward, more of it and stronger until the warm air snuffs out, the funnel choked, thinning and lifting away. It stretches into a long ribbon, harmless now, twirling across the sky.”

My rating:

Twister, Genanne Walsh’s debut novel, was published by Black Lawrence Press in 2015 and won the publisher’s Big Moose Prize. My thanks to the author for sending a free copy for review.

Painful but Necessary: Culling Books, Etc.

I’ve been somewhat cagey about the purpose for my trip back to the States. Yes, it was about helping my parents move, but the backstory to that is that they’re divorcing after 44 years of marriage and so their home of 13 years, one of three family homes I’ve known, is being sold. It was pretty overwhelming to see all the stacks of stuff in the garage. I was reminded of these jolting lines from Nausheen Eusuf’s lush poem about her late parents’ house, “Musée des Beaux Morts”: “Well, there you have it, folks, the crap / one collects over a lifetime.”

On the 7th I moved my mom into her new retirement community, and in my two brief spells back at the house I was busy dealing with the many, many boxes I’ve stored there for years. In the weeks leading up to my trip I’d looked into shipping everything back across the ocean, but the cost would have been in the thousands of dollars and just wasn’t worth it. Although my dad is renting a storage unit, so I’m able to leave a fair bit behind with him, I knew that a lot still had to go. Even (or maybe especially) books.

Had I had more time at my disposal, I might have looked into eBay and other ways to maximize profits, but with just a few weeks and limited time in the house itself, I had to go for the quickest and easiest options. I’m a pretty sentimental person, but I tried to approach the process rationally to minimize my emotional overload. I spent about 24 hours going through all of my boxes of books, plus the hundreds of books and DVDs my parents had set aside for sale, and figuring out the best way to dispose of everything. Maybe these steps will help you prepare for a future move.

The Great Book Sort-Out in progress.

When culling books, I asked myself:

- Do I have duplicate copies? This was often the case for works by Dickens, Eliot and Hardy. I kept the most readable copy and put the others aside for sale.

- Have I read it and rated it 3 stars or below? I don’t need to keep the Ayn Rand paperback just to prove to myself that I got through all 1000+ pages. If I’m not going to reread Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres, better to put it in the local Little Free Library so someone else can enjoy it for the first time.

- Can I see myself referring to this again? My college philosophy textbook had good explanations and examples, but I can access pithy statements of philosophers’ beliefs on the Internet instead. I’d like to keep up conversational French, sure, but I doubt I’ll ever open up a handbook of unusual verb conjugations.

- Am I really going to read this? I used to amass classics with the best intention of inhaling them and becoming some mythically well-read person, but many have hung around for up to two decades without making it onto my reading stack. So it was farewell to everything by Joseph Fielding and Sinclair Lewis; to obscure titles by D.H. Lawrence and Anthony Trollope; and to impossible dreams like Don Quixote. If I have a change of heart in the future, these are the kinds of books I can find in a university library or download from Project Gutenberg.

My first port of call for reselling books was Bookscouter.com (the closest equivalents in the UK are WeBuyBooks and Ziffit). This is an American site that compares buyback offers from 30 secondhand booksellers. There’s a minimum number of books / minimum value you have to meet before you can complete a trade-in. You print off a free shipping label and then drop off the box at your nearest UPS depot or arrange for a free USPS pickup. I ended up sending boxes to Powell’s Books, TextbookRush and Sellbackyourbook and making nearly a dollar per book. Powell’s bought about 18 of my paperback fiction titles, while the other two sites took a bizarre selection of around 30 books each.

Some books that were in rather poor condition or laughably outdated got shunted directly into piles for the Little Free Library or a Salvation Army donation. Many of my mom’s older Christian living books and my dad’s diet and fitness books I sorted into categories to be sold by the box in an online auction after the house sells.

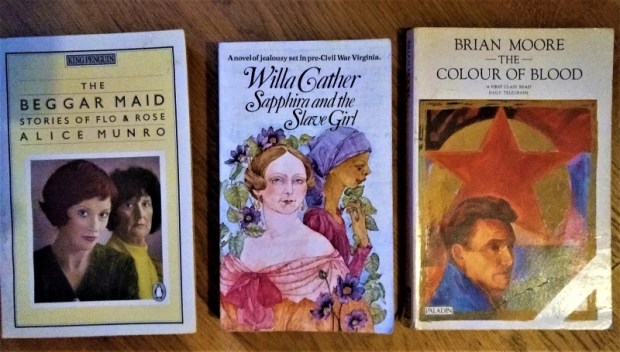

The final set of books awaiting sale.

All this still left about 18 boxes worth of rejects. For the non-antiquarian material I first tried 2nd & Charles, a new and secondhand bookstore chain that offers cash or store credit on select books. I planned to take the rest, including the antiquarian stuff, to an Abebooks seller in my mom’s new town, but I never managed to connect with him. So, the remaining boxes went to Wonder Book and Video, a multi-branch store I worked for during my final year of college. The great thing about them (though maybe not so great when you work there and have to sort through boxes full of dross) is that they accept absolutely everything when they make a cash offer. Although I felt silly selling back lots of literary titles I bought there over the years, at a massive loss, it was certainly an efficient way of offloading unwanted books.

As to everything else…

- I sent off 42.5 pounds (19.3 kilograms) of electronic waste to GreenDisk for recycling. That’s 75 VHS tapes, 63 CDs, 38 cassette tapes, 11 DVDs, five floppy disks, two dead cables, and one dead cell phone I saved from landfill, even if I did have to pay for the privilege.

- I donated all but a few of my jigsaw puzzles to my mom’s retirement community.

- I gave my mom my remaining framed artworks to display at her new place.

- I gave some children’s books, stuffed animals, games and craft supplies away to my nieces and nephews or friends’ kids.

- I let my step-nephew (if that’s a word) take whatever he wanted from my coin collection, and then sold that and most of my stamp collection back to a coin store.

- Most of my other collections – miniature tea sets, unicorn figurines, classic film memorabilia – all went onto the auction pile.

- My remaining furniture, a gorgeous rolltop desk plus a few bookcases, will also be part of the auction.

- You can tell I was in a mood to scale back: I finally agreed to throw out two pairs of worn-out shoes with holes in them, long after my mother had started nagging me about them.

Mementos and schoolwork have been the most difficult items for me to decide what to do with. Ultimately, I ran out of time and had to store most of the boxes as they were. But with the few that I did start to go through I tried to get in a habit of appreciating, photographing and then disposing. So I kept a handful of favorite essays and drawings, but threw out my retainers, recycled the science fair projects, and put the hand-knit baby clothes on the auction pile. (My mom kept the craziest things, like 12 inches of my hair from a major haircut I had in seventh grade – this I threw out at the edge of the woods for something to nest with.)

All this work and somehow I was still left with 29 smallish boxes to store with my dad’s stuff. Fourteen of these are full of books, with another four boxes of books stored in my mom’s spare room closet to select reading material from on future visits. So to an extent I’ve just put off the really hard work of culling until some years down the road – unless we ever move to the States, of course, in which case the intense downsizing would start over here.

All this work and somehow I was still left with 29 smallish boxes to store with my dad’s stuff. Fourteen of these are full of books, with another four boxes of books stored in my mom’s spare room closet to select reading material from on future visits. So to an extent I’ve just put off the really hard work of culling until some years down the road – unless we ever move to the States, of course, in which case the intense downsizing would start over here.

At any rate, in the end it’s all just stuff. What I’m really mourning, I know, is not what I had to get rid of, or even the house, but the end of our happy family life there. I didn’t know how to say goodbye to that, or to my hometown. I’ve got the photos and the memories, and those will have to suffice.

Have you had to face a mountain of stuff recently? What are your strategies for getting rid of books and everything else?

A CanLit Classic: The Stone Angel by Margaret Laurence

Hagar Shipley has earned the right to be curmudgeonly. Now 90 years old, she has already lived with her son Marvin and his wife Doris for 17 years when they spring a surprise on her: they want to sell the house and move somewhere smaller, and they mean to send her to Silver Threads nursing home. What with a recent fall, gallbladder issues and pesky constipation, the old woman’s health is getting to be more than Doris can handle at home. But don’t expect Hagar to give in without a fight.

This is one of those novels where the first-person voice draws you in immediately. “I am rampant with memory,” Hagar says, and as the book proceeds she keeps lapsing back, seemingly involuntarily, into her past. While in a doctor’s waiting room or in the derelict house by the coast where she runs away to escape the threat of the nursing home, she loses the drift of the present and in her growing confusion relives episodes from earlier life.

Many of these are melancholy: her mother’s early death and her difficult relationship with her father, an arrogant, self-made shopkeeper (“Both of us were blunt as bludgeons. We hadn’t a scrap of subtlety between us”); her volatile marriage to Bram, a common fellow considered unworthy of her (“Twenty-four years, in all, were scoured away like sand-banks under the spate of our wrangle and bicker”); and the untimely deaths of both a brother and a son.

The stone angel of the title is the monument on Hagar’s mother’s grave, but it is also an almost oxymoronic description for our protagonist herself. “The night my son died I was transformed to stone and never wept at all,” she remembers. Hagar is harsh-tongued and bitter, always looking for someone or something to blame. Yet she recognizes these tendencies in herself and sometimes overcomes her stubbornness enough to backtrack and apologize. What wisdom she has is hard won through suffering, but she’s still standing. “She’s a holy terror,” son Marvin describes her later in the novel: another paradox.

Originally from 1964, The Stone Angel was reprinted in the UK in September as part of the Apollo Classics series. It’s the first in Laurence’s Manawaka sequence of five novels, set in a fictional town based on her hometown in Manitoba, Canada. It could be argued that this novel paved the way for any number of recent books narrated by or about the elderly and telling of their surprise late-life adventures: everything from Jonas Jonasson’s The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out of the Window and Disappeared to Emma Hooper’s Etta and Otto and Russell and James. I was also reminded of Jane Smiley’s Midwest novels, and wondered if Carol Shields’s The Stone Diaries was possibly intended as an homage.

I loved spending time in Hagar’s company, whether she’s marveling at how age has crept up on her—

I feel that if I were to walk carefully up to my room, approach the mirror softly, take it by surprise, I would see there again that Hagar with the shining hair, the dark-maned colt off to the training ring

trying to picture life going on without her—

Hard to imagine a world and I not in it. Will everything stop when I do? Stupid old baggage, who do you think you are? Hagar. There’s no one like me in this world.

or simply describing a spring day—

The poplar bluffs had budded with sticky leaves, and the frogs had come back to the sloughs and sang like choruses of angels with sore throats, and the marsh marigolds were opening like shavings of sun on the brown river where the tadpoles danced and the blood-suckers lay slimy and low, waiting for the boys’ feet.

It was a delight to experience this classic of Canadian literature.

(The Apollo imprint will be publishing the second Manawaka book, A Jest of God, in March.)

With thanks to Blake Brooks at Head of Zeus/Apollo for the free copy for review.

My rating:

Now in November by Josephine Johnson

I’d never heard of this 1935 Pulitzer Prize winner before I saw a large display of titles from publisher Head of Zeus’s new imprint, Apollo, at Foyles bookshop in London the night of the Diana Athill event. Apollo, which launched with eight titles in April, aims to bring lesser-known classics out of obscurity: by making “great forgotten works of fiction available to a new generation of readers,” it intends to “challenge the established canon and surprise readers.” I’ll be reviewing Howard Spring’s My Son, My Son for Shiny New Books soon, and I’m tempted by the Eudora Welty and Christina Stead titles. Rounding out the list are two novels set in Eastern Europe, a Sardinian novel in translation, and an underrated Western.

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. She recognizes how unsuited her father, Arnold, was to farming: “He hadn’t the resignation that a farmer has to have – that resignation which knows how little use to hope or hate.” The remaining members of this female-dominated household are mother Willa, older sister Kerrin and younger sister Merle. Half-feral Kerrin is a creature apart. She’s always doing something unpredictable, like demonstrating knife-throwing to disastrous effect or taking over as the local schoolteacher, a job she’s not at all right for.

Missouri-born Johnson was just 24 years old when she published Now in November. The novel is narrated by the middle Haldmarne daughter, Marget, looking back at a grueling decade on the family farm. She recognizes how unsuited her father, Arnold, was to farming: “He hadn’t the resignation that a farmer has to have – that resignation which knows how little use to hope or hate.” The remaining members of this female-dominated household are mother Willa, older sister Kerrin and younger sister Merle. Half-feral Kerrin is a creature apart. She’s always doing something unpredictable, like demonstrating knife-throwing to disastrous effect or taking over as the local schoolteacher, a job she’s not at all right for.

The arrival of Grant Koven, a neighbor in his thirties hired to help Arnold with hard labor, seems like the only thing that might break the agricultural cycle of futile hope and disappointment. Marget quickly falls in love with him, but it takes her a while to realize that her sisters are smitten too. They all keep hoping their fortunes will change:

‘This year will have to be different,’ I thought. ‘We’ve scrabbled and prayed too long for it to end as the others have.’ The debt was still like a bottomless swamp unfilled, where we had gone year after year, throwing in hours of heat and the wrenching on stony land, only to see them swallowed up and then to creep back and begin again.

Yet as drought settles in, things only get worse. The fear of losing everything becomes a collective obsession; a sense of insecurity pervades the community. The Ramseys, black tenant farmers with nine children, are evicted. Milk producers go on strike and have to give the stuff away before it sours. Nature is indifferent and neither is there a benevolent God at work: when the Haldmarnes go to church, they are refused communion as non-members.

Marget skips around in time to pinpoint the central moments of their struggle, her often fragmentary thoughts joined by ellipses – a style that seemed to me ahead of its time:

if anything could fortify me against whatever was to come […] it would have to be the small and eternal things – the whip-poor-wills’ long liquid howling near the cave… the shape of young mules against the ridge, moving lighter than bucks across the pasture… things like the chorus of cicadas, and the ponds stained red in evenings.

Michael Schmidt, the critic who selected the first eight Apollo books, likens Now in November to the work of two very different female writers: Marilynne Robinson and Emily Brontë. What I think he is emphasizing with those comparisons is the sense of isolation and the feeling that struggle is writ large on the landscape. The Haldmarne sisters certainly wander the nearby hills like the Brontë sisters did the Yorkshire moors.

The cover image, reproduced in full on the endpapers, is Jackson Pollock’s “Man with Hand Plow,” c. 1933.

As points of reference I would also add Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres and Joan Chase’s During the Reign of the Queen of Persia (resurrected by NYRB Classics in 2014), which also give timeless weight to the female experience of Midwest farming. Like the Smiley, Now in November stars a trio of sisters and makes conscious allusions to King Lear. Kerrin reads the play and thinks of their father as Lear, while Marget quotes it as a prophecy that the worst is yet to come: “I remembered the awful words in Lear: ‘The worst is not so long as we can say “This is the worst.”’ Already this year, I’d cried, This is enough! uncounted times, and the end had never come.”

Johnson lived to age 80 and published another 11 books, but nothing ever lived up to the success of her first. This is an atmospheric and strangely haunting novel. The plot is simple enough, but the writing elevates it into something special. The plaintive tone, the folksy metaphors, and the philosophical earnestness all kept me eagerly traveling along with Marget to see where this tragic story might lead. Apollo has done the literary world a great favor in bringing this lost classic to light.

With thanks to Blake Brooks at Head of Zeus for the free copy.

My rating:

—but the mineral-heavy imagery (“the agate cups of your palms …the bronzed lamp of my breast”) is so weirdly archaic and the vocabulary so technical that I kept thinking of the Song of Solomon. Not that there’s anything wrong with that; it’s just not the model I expected to find.

—but the mineral-heavy imagery (“the agate cups of your palms …the bronzed lamp of my breast”) is so weirdly archaic and the vocabulary so technical that I kept thinking of the Song of Solomon. Not that there’s anything wrong with that; it’s just not the model I expected to find.

Meloy is from Montana and most of the 14 stories in this, her debut collection, are set in the contemporary American West among those who make their living from the outdoors, diving to work on hydroelectric dams or keeping cattle and horses. However, one of the more memorable stories, “Aqua Boulevard,” is set in Paris, where a geriatric father can’t tamp down his worries for his offspring.

Meloy is from Montana and most of the 14 stories in this, her debut collection, are set in the contemporary American West among those who make their living from the outdoors, diving to work on hydroelectric dams or keeping cattle and horses. However, one of the more memorable stories, “Aqua Boulevard,” is set in Paris, where a geriatric father can’t tamp down his worries for his offspring.

This is one of Smiley’s earlier works and feels a little generic, like she hadn’t yet developed a signature voice or themes. One summer, a 52-year-old mother of five prepares for her adult son Michael’s return from India after two years of teaching. His twin brother, Joe, will pick him up from the airport later on. Through conversations over dinner and a picnic in the park, the rest of the family try to work out how Michael has changed during his time away. “I try to accept the mystery of my children, of the inexplicable ways they diverge from parental expectations, of how, however much you know or remember of them, they don’t quite add up.” The narrator recalls her marriage-ending affair and how she coped afterwards. Michael drops a bombshell towards the end of the 91-page novella. Readable yet instantly forgettable, alas. I bought it as part of a dual volume with Good Will, which I don’t expect I’ll read. (Secondhand purchase,

This is one of Smiley’s earlier works and feels a little generic, like she hadn’t yet developed a signature voice or themes. One summer, a 52-year-old mother of five prepares for her adult son Michael’s return from India after two years of teaching. His twin brother, Joe, will pick him up from the airport later on. Through conversations over dinner and a picnic in the park, the rest of the family try to work out how Michael has changed during his time away. “I try to accept the mystery of my children, of the inexplicable ways they diverge from parental expectations, of how, however much you know or remember of them, they don’t quite add up.” The narrator recalls her marriage-ending affair and how she coped afterwards. Michael drops a bombshell towards the end of the 91-page novella. Readable yet instantly forgettable, alas. I bought it as part of a dual volume with Good Will, which I don’t expect I’ll read. (Secondhand purchase,

Some of these stories are disturbing: being stalked by a patient with a personality disorder, a man poisoning his girlfriend, a farmer predicting the very day and time of his death. A gynaecologist changes his mind about abortion after he meets a 15-year-old who gave birth at home and left her baby outside in a plastic bag to die of exposure. Other pieces are heart-warming: A paramedic delivers a premature, breech baby right in the ambulance. Staff throw a wedding at the hospital for a dying teen (as in Dear Life by Rachel Clarke). A woman diagnosed with cancer while pregnant has chemotherapy and a healthy baby – now a teenager. There’s even a tale from a vet who crowdfunded prostheses for a lively terrier.

Some of these stories are disturbing: being stalked by a patient with a personality disorder, a man poisoning his girlfriend, a farmer predicting the very day and time of his death. A gynaecologist changes his mind about abortion after he meets a 15-year-old who gave birth at home and left her baby outside in a plastic bag to die of exposure. Other pieces are heart-warming: A paramedic delivers a premature, breech baby right in the ambulance. Staff throw a wedding at the hospital for a dying teen (as in Dear Life by Rachel Clarke). A woman diagnosed with cancer while pregnant has chemotherapy and a healthy baby – now a teenager. There’s even a tale from a vet who crowdfunded prostheses for a lively terrier. Over a year of lockdowns, many of us have become accustomed to spending most of the time at home. But for Josie George, social isolation is nothing new. Chronic illness long ago reduced her territory to her home and garden. The magic of A Still Life is in how she finds joy and purpose despite extreme limitations. Opening on New Year’s Day and travelling from one winter to the next, the book is a window onto George’s quiet existence as well as the turning of the seasons. (My full review will appear in a forthcoming issue of the Times Literary Supplement. See also Eleanor’s thorough

Over a year of lockdowns, many of us have become accustomed to spending most of the time at home. But for Josie George, social isolation is nothing new. Chronic illness long ago reduced her territory to her home and garden. The magic of A Still Life is in how she finds joy and purpose despite extreme limitations. Opening on New Year’s Day and travelling from one winter to the next, the book is a window onto George’s quiet existence as well as the turning of the seasons. (My full review will appear in a forthcoming issue of the Times Literary Supplement. See also Eleanor’s thorough  1972. First we meet Clara, a plucky seven-year-old sitting vigil. She’s waiting for the return of two people: her sixteen-year-old sister, Rose, who ran away from home; and their next-door neighbour, Mrs. Orchard, whose cat, Moses, she’s feeding until the old lady gets back from the hospital. As days turn into weeks, though, it seems less likely that either will come home, and one day Clara sees a strange man moving boxes around in Mrs. Orchard’s house. This is Liam Kane, who’s inherited the house from a family friend. In his thirties and recently divorced, he’s taking a break in this tiny town, never imagining that he might find a new life. The third protagonist, and only first-person narrator, is Elizabeth, who lies in a hospital bed with heart trouble and voices her memories as a monologue to her late husband.

1972. First we meet Clara, a plucky seven-year-old sitting vigil. She’s waiting for the return of two people: her sixteen-year-old sister, Rose, who ran away from home; and their next-door neighbour, Mrs. Orchard, whose cat, Moses, she’s feeding until the old lady gets back from the hospital. As days turn into weeks, though, it seems less likely that either will come home, and one day Clara sees a strange man moving boxes around in Mrs. Orchard’s house. This is Liam Kane, who’s inherited the house from a family friend. In his thirties and recently divorced, he’s taking a break in this tiny town, never imagining that he might find a new life. The third protagonist, and only first-person narrator, is Elizabeth, who lies in a hospital bed with heart trouble and voices her memories as a monologue to her late husband. My summary for Bookmarks magazine: “A racehorse, Perestroika—nicknamed Paras—strays from her unlocked suburban stable one day, carrying her groom’s purse in her mouth, and ends up in Paris’s Place du Trocadéro. Here she meets Frida the dog, Sid and Nancy the mallards, and Raoul the raven. Frida, whose homeless owner died, knows about money. She takes euros from the purse to buy food from a local market, while Paras gets treats from a baker on predawn walks. Etienne, an eight-year-old orphan who lives with his ancient great-grandmother, visits the snowy park to feed the wary animals (who can talk to each other), and offers Paras a home. A sweet fable for animal lovers.”

My summary for Bookmarks magazine: “A racehorse, Perestroika—nicknamed Paras—strays from her unlocked suburban stable one day, carrying her groom’s purse in her mouth, and ends up in Paris’s Place du Trocadéro. Here she meets Frida the dog, Sid and Nancy the mallards, and Raoul the raven. Frida, whose homeless owner died, knows about money. She takes euros from the purse to buy food from a local market, while Paras gets treats from a baker on predawn walks. Etienne, an eight-year-old orphan who lives with his ancient great-grandmother, visits the snowy park to feed the wary animals (who can talk to each other), and offers Paras a home. A sweet fable for animal lovers.” (

(

(20 Books of Summer, #5) “Get that dried crap away from my bird!” That random line about herbs is one my husband and I remember from a Bourdain TV program and occasionally quote to each other. It’s a mild curse compared to the standard fare in this flashy memoir about what really goes on in restaurant kitchens. His is a macho, vulgar world of sex and drugs. In the “wilderness years” before he opened his Les Halles restaurant, Bourdain worked in kitchens in Baltimore and New York City and was addicted to heroin and cocaine. Although he eventually cleaned up his act, he would always rely on cigarettes and alcohol to get through ridiculously long days on his feet.

(20 Books of Summer, #5) “Get that dried crap away from my bird!” That random line about herbs is one my husband and I remember from a Bourdain TV program and occasionally quote to each other. It’s a mild curse compared to the standard fare in this flashy memoir about what really goes on in restaurant kitchens. His is a macho, vulgar world of sex and drugs. In the “wilderness years” before he opened his Les Halles restaurant, Bourdain worked in kitchens in Baltimore and New York City and was addicted to heroin and cocaine. Although he eventually cleaned up his act, he would always rely on cigarettes and alcohol to get through ridiculously long days on his feet. (20 Books of Summer, #6) I don’t know what took me so long to read another novel by Ruth Ozeki after A Tale for the Time Being, one of my favorite books of 2013. This is nearly as fresh, vibrant and strange. Set in 1991, it focuses on the making of a Japanese documentary series, My American Wife, sponsored by a beef marketing firm. Japanese American filmmaker Jane Takagi-Little is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. The traditional values and virtues of her two countries are in stark contrast, as are Main Street/Ye Olde America and the burgeoning Walmart culture.

(20 Books of Summer, #6) I don’t know what took me so long to read another novel by Ruth Ozeki after A Tale for the Time Being, one of my favorite books of 2013. This is nearly as fresh, vibrant and strange. Set in 1991, it focuses on the making of a Japanese documentary series, My American Wife, sponsored by a beef marketing firm. Japanese American filmmaker Jane Takagi-Little is tasked with finding all-American families and capturing their daily lives – and best meat recipes. The traditional values and virtues of her two countries are in stark contrast, as are Main Street/Ye Olde America and the burgeoning Walmart culture.

(20 Books of Summer, #7) I read the first couple of chapters, in which he plans his adventure, and then started skimming. I expected this to be a breezy read I would race through, but the voice was neither inviting nor funny. I also hoped to find more about non-chain supermarkets and restaurants – that’s why I put this on the pile for my foodie challenge in the first place – but, from a skim, it mostly seemed to be about car trouble, gas stations and fleabag motels. The only food-related moments are when Gorman (a vegetarian) downs three fast food burgers and orders of fries in 10 minutes and, predictably, vomits them all back up; and when he stops at an old-fashioned soda fountain for breakfast.

(20 Books of Summer, #7) I read the first couple of chapters, in which he plans his adventure, and then started skimming. I expected this to be a breezy read I would race through, but the voice was neither inviting nor funny. I also hoped to find more about non-chain supermarkets and restaurants – that’s why I put this on the pile for my foodie challenge in the first place – but, from a skim, it mostly seemed to be about car trouble, gas stations and fleabag motels. The only food-related moments are when Gorman (a vegetarian) downs three fast food burgers and orders of fries in 10 minutes and, predictably, vomits them all back up; and when he stops at an old-fashioned soda fountain for breakfast. (20 Books of Summer, #8) I read the first 25 pages and then started skimming. This is a story of a group of friends – paisanos, of mixed Mexican, Native American and Caucasian blood – in Monterey, California. During World War I, Danny serves as a mule driver and Pilon is in the infantry. When discharged from the Army, they return to Tortilla Flat, where Danny has inherited two houses. He lives in one and Pilon is his tenant in the other (though Danny will never see a penny in rent). They’re a pair of loveable scamps, like Huck Finn all grown up, stealing wine and chickens left and right.

(20 Books of Summer, #8) I read the first 25 pages and then started skimming. This is a story of a group of friends – paisanos, of mixed Mexican, Native American and Caucasian blood – in Monterey, California. During World War I, Danny serves as a mule driver and Pilon is in the infantry. When discharged from the Army, they return to Tortilla Flat, where Danny has inherited two houses. He lives in one and Pilon is his tenant in the other (though Danny will never see a penny in rent). They’re a pair of loveable scamps, like Huck Finn all grown up, stealing wine and chickens left and right.