20 Books of Summer, #7–10: Auster, Darlington, Durrell, Jansma

Owls and leopards and dogs – oh my! My animal-themed reading project continues. I’m more than halfway through in that I’m in the middle of quite a few more books, but finishing and reviewing them all before the 3rd of September may still prove to be a challenge.

Timbuktu by Paul Auster (1999)

My first from Auster – and not, I take it, representative of his work in general. Never mind, though; I enjoyed it, and it was a good follow-up to Fifteen Dogs. Like the Alexis novel, this gives an intimately imagined dog’s perspective, taking seriously the creature’s whole life story. The canine protagonist is Mr. Bones, who’s accompanied his mentally unstable writer owner, Willy G. Christmas, from New York City down to Baltimore, where, one August Sunday, Willy wants to find his old high school English teacher before he dies.

My first from Auster – and not, I take it, representative of his work in general. Never mind, though; I enjoyed it, and it was a good follow-up to Fifteen Dogs. Like the Alexis novel, this gives an intimately imagined dog’s perspective, taking seriously the creature’s whole life story. The canine protagonist is Mr. Bones, who’s accompanied his mentally unstable writer owner, Willy G. Christmas, from New York City down to Baltimore, where, one August Sunday, Willy wants to find his old high school English teacher before he dies.

What took me by surprise is that Auster doesn’t stick with Willy, but has Mr. Bones move on to two more living situations: first he’s the secret friend of 10-year-old Henry Chow, whose parents run a Chinese restaurant, then he’s a family pet in suburban Virginia. Although his English comprehension is advanced, he isn’t able to reproduce its sounds like some of the dogs in Fifteen Dogs can, so he can’t tell these new owners his real name and has to accept being called first “Cal” and then “Sparky.” In dreams he still hears Willy’s voice. He assumes Willy is now in the afterlife (“Timbuktu”), and longs to rejoin him.

The novel is tender as well as playful and funny – I loved the passage where Mr. Bones wakes up to pain but doesn’t realize he’s been castrated:

How was he to know that those missing parts had been responsible for turning him into a father many times over? Except for his ten-day affair with Greta, the malamute from Iowa City, his romances had always been brief—impetuous couplings, impromptu flings, frantic rolls in the hay—and he had never seen any of the pups he had sired. And even if he had, how would he have been able to make the connection? Dick Jones had turned him into a eunuch, but in his own eyes he was still the prince of love, the lord of the canine Romeos, and he would go on courting the ladies until his last, dying breath. For once, the tragic dimension of his own life eluded him.

Owl Sense by Miriam Darlington (2018)

Initially the idea was to see all of Britain’s resident owls, but as often happens, the project expanded until Darlington was also taking trips to Serbia to find a Long-Eared Owl, Finland for a Eurasian Eagle Owl, and France for a Pygmy Owl; and going on a fruitless twitch to see a vagrant Snowy Owl in Cornwall. Each chapter considers a different species and includes information on its anatomy, geographical distribution, conservation status, and any associated myths and anecdotes (The Secret Life of the Owl by John Lewis-Stempel does much the same thing, but with less richness). She has closer encounters with some than with others: when volunteering with the Barn Owl Trust, she gets to ring chicks and collects pellets for dissection. But even the most fleeting sightings can be magical.

Initially the idea was to see all of Britain’s resident owls, but as often happens, the project expanded until Darlington was also taking trips to Serbia to find a Long-Eared Owl, Finland for a Eurasian Eagle Owl, and France for a Pygmy Owl; and going on a fruitless twitch to see a vagrant Snowy Owl in Cornwall. Each chapter considers a different species and includes information on its anatomy, geographical distribution, conservation status, and any associated myths and anecdotes (The Secret Life of the Owl by John Lewis-Stempel does much the same thing, but with less richness). She has closer encounters with some than with others: when volunteering with the Barn Owl Trust, she gets to ring chicks and collects pellets for dissection. But even the most fleeting sightings can be magical.

The book also subtly weaves in what was happening in Darlington’s life at the time, especially her son Benji’s struggles. On the autistic spectrum, he suddenly started having physical problems that were eventually explained by non-epileptic seizures. I would have welcomed more personal material, but that just speaks to my love of memoir. This feels slightly hurried and not quite as editorially polished as her master work, Otter Country, but it’s still well worth reading if you have any interest in birds or nature conservation. (I’ve only seen two owls in the wild: Barn and Tawny.)

Fillets of Plaice by Gerald Durrell (1971)

This is a pleasant miscellany of leftover essays that didn’t make it into any of Durrell’s other books. The best is “The Birthday Party,” about an incident from the Corfu years: Larry insisted on taking the fridge along on Mother’s birthday outing to an island, and their boat ran out of petrol. In “A Transport of Terrapins,” teenage Gerry works as a lowly pet shop assistant in London even though he knows twice as much as his boss; and meets other eccentric fellows, such as a bird collector and a retired colonel who has a house full of model figures for war gaming.

This is a pleasant miscellany of leftover essays that didn’t make it into any of Durrell’s other books. The best is “The Birthday Party,” about an incident from the Corfu years: Larry insisted on taking the fridge along on Mother’s birthday outing to an island, and their boat ran out of petrol. In “A Transport of Terrapins,” teenage Gerry works as a lowly pet shop assistant in London even though he knows twice as much as his boss; and meets other eccentric fellows, such as a bird collector and a retired colonel who has a house full of model figures for war gaming.

“A Question of Promotion” is set on one of the animal-collecting expeditions to Cameroon and turned me off a little with its colonial attitude: Durrell talks to the natives in condescending pidgin as he helps prepare a feast for the District Commissioner’s visit. In “A Question of Degrees” he visits two hospitals for a cataclysmic nosebleed, while “Ursula” is about a girlfriend who couldn’t open her mouth without uttering a malapropism. Entertaining scraps for diehard fans; if you’re new to Durrell, though, start with My Family and Other Animals and Menagerie Manor.

The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards by Kristopher Jansma (2013)

I’d meant to read Jansma’s debut ever since Why We Came to the City, his terrific novel about five university friends negotiating life in New York City during the recession, came out in 2016. I assumed the leopards of the title would be purely metaphorical – a reference to people not being able to change their inborn nature – and they are, but they’re also surprisingly literal in the one chapter set in Africa.

I’d meant to read Jansma’s debut ever since Why We Came to the City, his terrific novel about five university friends negotiating life in New York City during the recession, came out in 2016. I assumed the leopards of the title would be purely metaphorical – a reference to people not being able to change their inborn nature – and they are, but they’re also surprisingly literal in the one chapter set in Africa.

Jansma’s deliciously unreliable narrator, never named but taking on various aliases in these linked short stories, is a trickster, constantly reworking his life into fiction. He longs to be a successful novelist, but keeps losing his works in progress. We think we know the basics of his identity – he’s the son of a single mother who worked as a flight attendant; he grew up in North Carolina emulating the country club and debutante class; at Berkshire College he met his best friend and rival Julian McGann in creative writing class and fell for Julian’s friend Evelyn, the great unrequited love of his life – but Part II introduces doubt by calling the characters different names. Are these the ‘real’ people, or the narrator’s fictionalized versions?

The characters go on a bizarre odyssey that moves the setting from New York City to Nevada to Dubai to Sri Lanka to Ghana to Iceland to Luxembourg, finally ending up back in the very airport terminal where it started. As I remembered from Why We Came to the City, Jansma interleaves Greek mythology and allusions to other writers, especially F. Scott Fitzgerald. The coy way in which he layers fiction on fiction reminded me of work by John Boyne and Tom Rachman; other recommended readalikes are The Goldfinch and Orchid & the Wasp.

March’s Doorstopper: Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese (2009)

I’m squeaking in here on the 31st with the doorstopper I’ve been reading all month. I started Cutting for Stone in an odd situation on the 1st: We’d attempted to go to France that morning but were foiled by a fatal engine failure en route to the ferry terminal, so were riding in the cab of a recovery vehicle that was taking us and our car home. My poor husband sat beside the driver, trying to make laddish small talk about cars, while I wedged myself by the window and got lost in the early pages of Indian-American doctor Abraham Verghese’s saga of twins Marion and Shiva, born of an unlikely union between an Indian nun, Sister Mary Joseph Praise, and an English surgeon, Thomas Stone, at Missing Hospital in Addis Ababa in 1954.

What with the flashbacks and the traumatic labor, it takes narrator Marion over 100 pages to get born. That might seem like a Tristram Shandy degree of circumlocution, but there was nary a moment when my interest flagged during this book’s 50-year journey with a medical family starting in a country I knew nothing about. I was reminded of Midnight’s Children, in that the twin brothers are born loosely conjoined at the head and ever after have a somewhat mystical connection, understanding each other’s thoughts even when they’re continents apart.

What with the flashbacks and the traumatic labor, it takes narrator Marion over 100 pages to get born. That might seem like a Tristram Shandy degree of circumlocution, but there was nary a moment when my interest flagged during this book’s 50-year journey with a medical family starting in a country I knew nothing about. I was reminded of Midnight’s Children, in that the twin brothers are born loosely conjoined at the head and ever after have a somewhat mystical connection, understanding each other’s thoughts even when they’re continents apart.

When Sister Mary Joseph Praise dies in childbirth and Stone absconds, the twins are raised by the hospital’s blunt obstetrician, Hema, and her husband, a surgeon named Ghosh. Both brothers follow their adoptive parents into medicine and gain knowledge of genitourinary matters. We observe a vasectomy, a breech birth, a C-section, and the aftermath of female genital mutilation. While Marion relocates to an inner-city New York hospital, Shiva stays in Ethiopia and becomes a world expert on vaginal fistulas. The novel I kept thinking about was The Cider House Rules, which is primarily about orphans and obstetrics, and I was smugly confirmed by finding Verghese’s thanks to his friend John Irving in the acknowledgments.

Ethiopia’s postcolonial history is a colorful background, with Verghese giving a bystander’s view of the military coup against the Emperor and the rise of the Eritrean liberation movement. Like Marion, the author is an Indian doctor who came of age in Ethiopia, a country he describes as a “juxtaposition of culture and brutality, this molding of the new out of the crucible of primeval mud.” Marion’s experiences in New York City and Boston then add on the immigrant’s perspective on life in the West in the 1980s onwards.

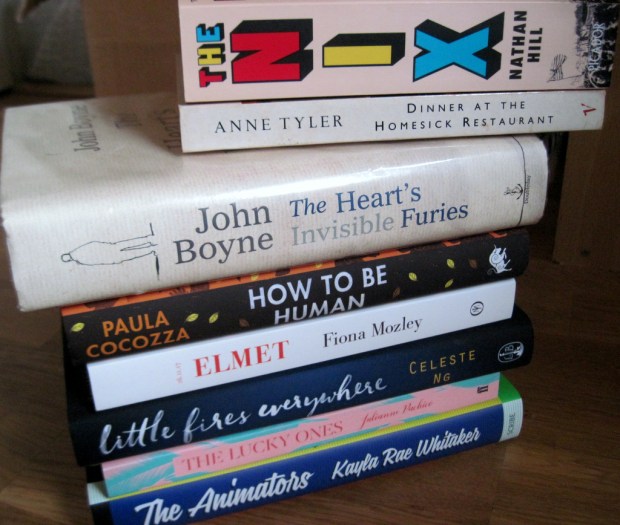

Naomi of Consumed by Ink predicted long ago that I’d love this, and she was right. Of course I thrilled to the accounts of medical procedures, such as an early live-donor liver transplant (this was shortlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize in 2009), but that wasn’t all that made Cutting for Stone such a winner for me. I can’t get enough of sprawling Dickensian stories in which coincidences abound (“The world turns on our every action, and our every omission, whether we know it or not”), minor characters have heroic roles to play, and humor and tragedy balance each other out, if ever so narrowly. (Besides Irving, think of books like The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne.) What I’m saying, as I strive to finish this inadequate review in the last hour of the last day of the month, is that this was just my sort of thing, and I hope I’ve convinced you that it might be yours, too.

Favorite lines:

Hema: “The Hippocratic oath is if you are sitting in London and drinking tea. No such oaths here in the jungle. I know my obligations.”

“Doubt is a first cousin to faith”

“A childhood at Missing imparted lessons about resilience, about fortitude, and about the fragility of life. I knew better than most children how little separate the world of health from that of disease, living flesh from the icy touch of the dead, the solid ground from treacherous bog.”

Page count: 667

My rating:

Next month: Since Easter falls in April and I’ve been wanting to read it for ages anyway, I’ve picked out The Resurrection of Joan Ashby by Cherise Wolas to start tomorrow.

Reading Ireland Month 2018: Seamus Deane and Edna O’Brien

It’s my first time participating in Reading Ireland Month, run each March by Cathy of 746 Books and Niall of The Fluff is Raging. I enjoyed scouring my shelves for Irish reads – though in the end I only had time for two.

Reading in the Dark by Seamus Deane (1996)

I don’t recall how I first heard about this book, but its title was familiar to me when I picked it up for a matter of pence at a charity shop last year. When I saw it on Cathy’s recent list of her top five Irish books of all time, I knew I was in for something special. These vivid vignettes of childhood and young adulthood are so convincing that I could have been fooled into believing I was reading a memoir. Indeed, this debut novel has generally been interpreted as heavily autobiographical, with the anonymous narrator, the third of seven children born to Catholic parents in Derry, Northern Ireland, taken to be a stand-in for Deane.

Ireland’s internecine violence is the sinister backdrop to this family’s everyday sorrows, including the death of a child and the mother’s shaky mental health. The narrator also learns a family secret from his dying maternal grandfather that at first thrills him – he knows something his father doesn’t! – but later serves to drive him away from his parents. The short chapters take place between 1945 and 1971: starting when the boy is five years old and encountering a household ghost on the stairs and ending as, in his early thirties, he lays his father to rest in the midst of the Troubles.

Ireland’s internecine violence is the sinister backdrop to this family’s everyday sorrows, including the death of a child and the mother’s shaky mental health. The narrator also learns a family secret from his dying maternal grandfather that at first thrills him – he knows something his father doesn’t! – but later serves to drive him away from his parents. The short chapters take place between 1945 and 1971: starting when the boy is five years old and encountering a household ghost on the stairs and ending as, in his early thirties, he lays his father to rest in the midst of the Troubles.

The Irish have such a knack for holding humor and tragedy up side by side – think John Boyne, James Joyce and Frank McCourt. The one force doesn’t negate the other, but the juxtaposition reminds you that life isn’t all gloom or laughs. There are some terrifically funny incidents in Reading in the Dark, like the individual sex ed. chat with Father Nugent (“And semen is the Latin for seed. Do you have to know Latin to do this?”) and going to investigate the rumor of a brothel by the football ground. But there is also perhaps the best ghost story I’ve ever read, an eerie tale of shape-shifting children he hears from his aunt.

This book captures all the magic, uncertainty and heartache of being a child, in crisp scenes I saw playing out in my mind. If I have one small, strange complaint, it’s that there’s too much plot – most of the chapters function perfectly well as stand-alone short stories, so, particularly in the last third, the growing obsession with the family secret feels like an unnecessary attempt to tie everything together. That plus the slight irrelevance of the title are the only reasons this misses out on 5 stars from me.

Still, I’d agree with Cathy: this is probably one of my favorite Irish reads, along with Boyne’s The Heart’s Invisible Furies, Mary Costello’s Academy Street, Anne Enright’s The Green Road, and Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It’s no wonder Deane won so many prizes for this: the Irish Times International Fiction Prize, the Guardian Fiction Prize, and the Irish Literature Prize; he was also shortlisted for the 1996 Booker Prize.

Favorite lines:

“Child, she’d tell me, I think sometimes you’re possessed. Can’t you just let the past be the past?”

“He looked up at me, smiling, to say: ah well, it was all blood under the bridge now”

“Politics destroyed people’s lives in this place, he said. People were better not knowing some things”

My rating:

Mother Ireland by Edna O’Brien (1976)

This slim volume combines travel writing, history and memoir, with plentiful black and white photographs (by Fergus Bourke) along the way. Often, even where O’Brien is clearly drawing on autobiographical material, she resists saying “I”, instead opting for “one,” “you,” or “we.” I think she was aiming at the universalities of the Irish experience, but instead it ends up coming off as generic. That and a long opening chapter on Ireland’s history set me to skimming. (Also, the book is maddeningly underpunctuated, and the photos in particular seem very dated.) By far my favorite of the seven essays was the last, “Escape to England.” In just three pages, she explains what it’s like to start a new life in another country and how the experience allowed her to appreciate home all the more. Should I try O’Brien’s fiction?

This slim volume combines travel writing, history and memoir, with plentiful black and white photographs (by Fergus Bourke) along the way. Often, even where O’Brien is clearly drawing on autobiographical material, she resists saying “I”, instead opting for “one,” “you,” or “we.” I think she was aiming at the universalities of the Irish experience, but instead it ends up coming off as generic. That and a long opening chapter on Ireland’s history set me to skimming. (Also, the book is maddeningly underpunctuated, and the photos in particular seem very dated.) By far my favorite of the seven essays was the last, “Escape to England.” In just three pages, she explains what it’s like to start a new life in another country and how the experience allowed her to appreciate home all the more. Should I try O’Brien’s fiction?

Favorite lines:

“Irish people do not like to be contradicted. Foiled again and again[,] they have in them a rage that comes at you unawares like a briar jutting out of a hedge.”

“You are Irish[,] you say lightly, and allocated to you are the tendencies to be wild, wanton, drunk, superstitious, unreliable, backward, toadying and prone to fits, whereas you know that in fact a whole entourage of ghosts resides in you, ghosts with whom the inner rapport is as frequent, as perplexing, as defiant as with any of the living.”

My rating:

No time for these this year – maybe next year, if not sooner?

December’s Doorstopper: The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne

The more I examined the architecture of my life, the more I realized how fraudulent were its foundations.

This is a book that wasn’t even on my radar until fairly late on in the year, when I noticed just how many of my Goodreads friends had read it and rated it – almost without fail – 5 stars. I knew John Boyne’s name only through the movie version of his Holocaust-set novel for younger readers, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, and didn’t think I’d be interested in his work. But the fact that The Heart’s Invisible Furies was written in homage to John Irving (Boyne’s dedicatee) piqued my interest, and I’m so glad I gave it a try. It distills all the best of Irving’s tendencies while eschewing some of his more off-putting ones. Of the Irving novels I’ve read, this is most like The World According to Garp and In One Person, with which it shares, respectively, a strong mother–son relationship and a fairly explicit sexual theme.

A wonderful seam of humor tempers the awfulness of much of what befalls Cyril Avery, starting with his indifferent adoptive parents, Charles and Maude. Charles is a wealthy banker and incorrigible philanderer occasionally imprisoned for tax evasion, while Maude is a chain-smoking author whose novels, to her great disgust, are earning her a taste of celebrity. Both are cold and preoccupied, always quick to remind Cyril that since he’s adopted he’s “not a real Avery”. The first bright spot in Cyril’s life comes when, at age seven, he meets Julian Woodbead, the son of his father’s lawyer. They become lifelong friends, though Cyril’s feelings are complicated by an unrequited crush. Julian is as ardent a heterosexual as Cyril is a homosexual, and sex drives them apart in unexpected and ironic ways in the years to come.

A wonderful seam of humor tempers the awfulness of much of what befalls Cyril Avery, starting with his indifferent adoptive parents, Charles and Maude. Charles is a wealthy banker and incorrigible philanderer occasionally imprisoned for tax evasion, while Maude is a chain-smoking author whose novels, to her great disgust, are earning her a taste of celebrity. Both are cold and preoccupied, always quick to remind Cyril that since he’s adopted he’s “not a real Avery”. The first bright spot in Cyril’s life comes when, at age seven, he meets Julian Woodbead, the son of his father’s lawyer. They become lifelong friends, though Cyril’s feelings are complicated by an unrequited crush. Julian is as ardent a heterosexual as Cyril is a homosexual, and sex drives them apart in unexpected and ironic ways in the years to come.

For Cyril, born in Dublin in 1945, homosexuality seems a terrible curse. It was illegal in Ireland until 1993, so assignations had to be kept top-secret to avoid police persecution and general prejudice. Only when he leaves for Amsterdam and the USA is Cyril able to live the life he wants. The structure of the novel works very well: Boyne checks in on Cyril every seven years, starting with the year of his birth and ending in the year of his death. In every chapter we quickly adjust to a new time period, deftly and subtly marked out by a few details, and catch up on Cyril’s life. Sometimes we don’t see the most climactic moments; instead, we see what happened just before and then Cyril remembers the aftermath for us years later. It’s an effective tour through much of the twentieth century and beyond, punctuated by the AIDS crisis and focusing on the status of homosexuals in Ireland – in 2015 same-sex marriage was legalized, which would have seemed unimaginable a few short decades before.

Boyne also sustains a dramatic irony that kept me reading eagerly: the book opens with the story Cyril’s birth mother told him of her predicament in 1945, and in later chapters Cyril keeps running into this wonderfully indomitable woman in Dublin – but neither of them realizes how intimately they’re connected. Thanks to the first chapter we know they eventually meet and all will be revealed, but exactly when and how is a delicious mystery.

Along with Irving, Dickens must have been a major influence on Boyne. I spotted traces of David Copperfield and Great Expectations in minor characters’ quirks as well as in Cyril’s orphan status, excessive admiration of a romantic interest, and frequent maddening failures to do the right thing. But there are several other recent novels – all doorstoppers – that are remarkably similar in their central themes and questions. In Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life and Nathan Hill’s The Nix we also have absent or estranged mothers; friends, lovers and adoptive family who help cut through a life of sadness and pain; and the struggle against a fate that seems to force one to live a lie. Given a span of 500 pages or more, it’s easy to become thoroughly engrossed in the life of a flawed character.

The Heart’s Invisible Furies – a phrase Hannah Arendt used to describe the way W.H. Auden wore his experiences on his face – is an alternately heartbreaking and heartening portrait of a life lived in defiance of intolerance and tragedy. A very Irish sense of humor runs all through the dialogue and especially Maude’s stubborn objection to fame. I loved Boyne’s little in-jokes about the writer’s life (“It’s a hideous profession. Entered into by narcissists who think their pathetic little imaginations will be of interest to people they’ve never met”) and thanks to my recent travels I was able to picture a lot of the Dublin and Amsterdam settings. Although it’s been well reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic, I’m baffled that this novel doesn’t have the high profile it deserves. I am especially grateful to Sarah of Sarah’s Book Shelves for naming this her book of the year: knowing her discriminating tastes, I could tell I’d be in for something special. Look out for it on my Best Fiction of 2017 list tomorrow.

My rating:

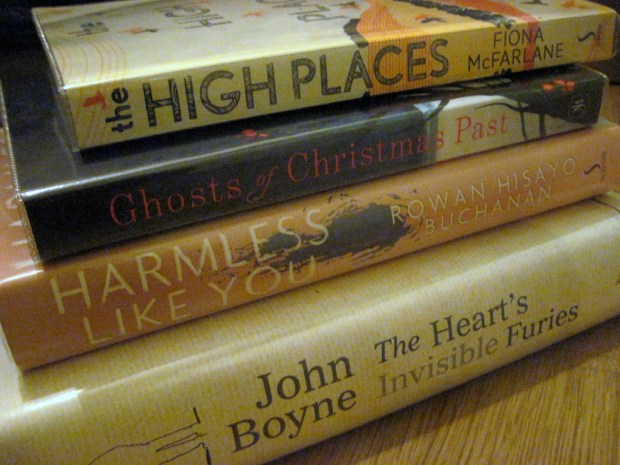

I got just four books for Christmas this year, but they’re all ones I’m very excited to read. I looked back at last year’s Christmas book haul photo and am impressed that I’ve actually read seven out of eight of them now – and the eighth is a cocktail cookbook one wouldn’t read all the way through anyway. All too often I let books sit around for years unread, but I will try to keep up this trend of reading books fairly soon after they enter my collection.

Library Checkout: December 2017

Posting early this month so that I’m not a nuisance on Christmas Day…

Most of the usual suspects from last month are still hanging around waiting to be read, though I also got (small!) fresh stacks out from both the public library and the university library.

LIBRARY BOOKS READ

- Our Endless Numbered Days by Claire Fuller

CURRENTLY READING

- Herzog by Saul Bellow

- The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne

- The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat by Oliver Sacks

- Spirals in Time: The Secret Life and Curious Afterlife of Seashells by Helen Scales

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

Public library

University library

Still out from the university library:

- This Cold Heaven: Seven Seasons in Greenland by Gretel Ehrlich

- To the Is-land: An Autobiography by Janet Frame

- Vita Nova [poetry] by Louise Glück

- The Cabaret of Plants: Botany and the Imagination by Richard Mabey

- There Is an Anger that Moves [poetry] by Kei Miller

- And When Did You Last See Your Father? by Blake Morrison

- The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

- The Magnificent Spinster by May Sarton

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- The Cat Who Stayed for Christmas by Cleveland Amory

- Howl, Kaddish and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg

RETURNED UNREAD

- Fresh Complaint: Stories by Jeffrey Eugenides – I’ve read all of his novels, so felt that I should at least try his short stories, but a glance at the table of contents made my heart sink. All of the stories are at least 20 pages long, and one is titled “The Oracular Vulva” (?!). I still have this on my Kindle, so perhaps I’ll try it another time.

What have you been reading from your local libraries? Does anything appeal from my stacks?

Merry Christmas to all!

*Frieda by Annabel Abbs: If you rely only on the words of D.H. Lawrence, you’d think Frieda was lucky to shed a dull family life and embark on an exciting set of bohemian travels with him as he built his name as a writer; Abbs adds nuance to that picture by revealing just how much Frieda was giving up, and the sorrow she left behind her. Frieda’s determination to live according to her own rules makes her a captivating character.

*Frieda by Annabel Abbs: If you rely only on the words of D.H. Lawrence, you’d think Frieda was lucky to shed a dull family life and embark on an exciting set of bohemian travels with him as he built his name as a writer; Abbs adds nuance to that picture by revealing just how much Frieda was giving up, and the sorrow she left behind her. Frieda’s determination to live according to her own rules makes her a captivating character. A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne: A delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view before getting Maurice’s own perspective; by this point we know enough to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is.

A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne: A delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view before getting Maurice’s own perspective; by this point we know enough to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is. The Overstory by Richard Powers: A sprawling novel about regular people who through various unpredictable routes become so devoted to trees that they turn to acts, large and small, of civil disobedience to protest the clear-cutting of everything from suburban gardens to redwood forests. I admired pretty much every sentence, whether it’s expository or prophetic.

The Overstory by Richard Powers: A sprawling novel about regular people who through various unpredictable routes become so devoted to trees that they turn to acts, large and small, of civil disobedience to protest the clear-cutting of everything from suburban gardens to redwood forests. I admired pretty much every sentence, whether it’s expository or prophetic. You Think It, I’ll Say It by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld describes families and romantic relationships expertly, in prose so deliciously smooth it slides right down. These 11 stories are about marriage, parenting, authenticity, celebrity and social media in Trump’s America. Overall, this is a whip-smart, current and relatable book, ideal for readers who don’t think they like short stories.

You Think It, I’ll Say It by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld describes families and romantic relationships expertly, in prose so deliciously smooth it slides right down. These 11 stories are about marriage, parenting, authenticity, celebrity and social media in Trump’s America. Overall, this is a whip-smart, current and relatable book, ideal for readers who don’t think they like short stories. *Meet Me at the Museum by Anne Youngson: A charming, bittersweet novel composed entirely of the letters that pass between Tina Hopgood, a 60-year-old farmer’s wife in East Anglia, and Anders Larsen, a curator at the Silkeborg Museum in Denmark. It’s a novel about second chances in the second half of life, and has an open but hopeful ending. I found it very touching and wish it hadn’t been given the women’s fiction treatment.

*Meet Me at the Museum by Anne Youngson: A charming, bittersweet novel composed entirely of the letters that pass between Tina Hopgood, a 60-year-old farmer’s wife in East Anglia, and Anders Larsen, a curator at the Silkeborg Museum in Denmark. It’s a novel about second chances in the second half of life, and has an open but hopeful ending. I found it very touching and wish it hadn’t been given the women’s fiction treatment. Rough Beauty: Forty Seasons of Mountain Living by Karen Auvinen: An excellent memoir that will have broad appeal with its themes of domestic violence, illness, grief, travel, wilderness, solitude, pets, wildlife, and relationships. A great example of how unchronological autobiographical essays can together build a picture of a life.

Rough Beauty: Forty Seasons of Mountain Living by Karen Auvinen: An excellent memoir that will have broad appeal with its themes of domestic violence, illness, grief, travel, wilderness, solitude, pets, wildlife, and relationships. A great example of how unchronological autobiographical essays can together build a picture of a life. *Heal Me: In Search of a Cure by Julia Buckley: Buckley takes readers along on a rollercoaster ride of new treatment ideas and periodically dashed hopes during four years of chronic pain. I was morbidly fascinated with this story, which is so bizarre and eventful that it reads like a great novel.

*Heal Me: In Search of a Cure by Julia Buckley: Buckley takes readers along on a rollercoaster ride of new treatment ideas and periodically dashed hopes during four years of chronic pain. I was morbidly fascinated with this story, which is so bizarre and eventful that it reads like a great novel. *This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein: A wry, bittersweet look at the unpredictability of life as an idealistic young woman in the world’s major cities. Another great example of life writing that’s not comprehensive or strictly chronological yet gives a clear sense of the self in the context of a family and in the face of an uncertain future.

*This Really Isn’t About You by Jean Hannah Edelstein: A wry, bittersweet look at the unpredictability of life as an idealistic young woman in the world’s major cities. Another great example of life writing that’s not comprehensive or strictly chronological yet gives a clear sense of the self in the context of a family and in the face of an uncertain future. *The Pull of the River: Tales of Escape and Adventure on Britain’s Waterways by Matt Gaw: This jolly yet reflective book traces canoe trips down Britain’s rivers, a quest to (re)discover the country by sensing the currents of history and escaping to the edge of danger. Gaw’s expressive writing renders even rubbish- and sewage-strewn landscapes beautiful.

*The Pull of the River: Tales of Escape and Adventure on Britain’s Waterways by Matt Gaw: This jolly yet reflective book traces canoe trips down Britain’s rivers, a quest to (re)discover the country by sensing the currents of history and escaping to the edge of danger. Gaw’s expressive writing renders even rubbish- and sewage-strewn landscapes beautiful. The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century by Kirk Wallace Johnson: A delightful read that successfully combines many genres – biography, true crime, ornithology, history, travel and memoir – to tell the story of an audacious heist of rare bird skins from the Natural History Museum at Tring in 2009. This is the very best sort of nonfiction: wide-ranging, intelligent and gripping.

The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century by Kirk Wallace Johnson: A delightful read that successfully combines many genres – biography, true crime, ornithology, history, travel and memoir – to tell the story of an audacious heist of rare bird skins from the Natural History Museum at Tring in 2009. This is the very best sort of nonfiction: wide-ranging, intelligent and gripping. *No One Tells You This by Glynnis MacNicol: There was a lot of appeal for me in how MacNicol sets out her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. She is daring and candid in examining her preconceptions and asking what she really wants from her life. And she tells a darn good story: I read this much faster than I generally do with a memoir.

*No One Tells You This by Glynnis MacNicol: There was a lot of appeal for me in how MacNicol sets out her 40th year as an adventure into the unknown. She is daring and candid in examining her preconceptions and asking what she really wants from her life. And she tells a darn good story: I read this much faster than I generally do with a memoir. The Library Book by Susan Orlean: This is really two books in one. The first is a record of the devastating fire at the Los Angeles Central Library on April 29, 1986 and how the city and library service recovered. The second is a paean to libraries in general: what they offer to society, and how they work, in a digital age. Sure to appeal to any book-lover.

The Library Book by Susan Orlean: This is really two books in one. The first is a record of the devastating fire at the Los Angeles Central Library on April 29, 1986 and how the city and library service recovered. The second is a paean to libraries in general: what they offer to society, and how they work, in a digital age. Sure to appeal to any book-lover. Help Me!: One Woman’s Quest to Find Out if Self-Help Really Can Change Her Life by Marianne Power: I have a particular weakness for year-challenge books, and Power’s is written in an easy, chatty style, as if Bridget Jones had given over her diary to testing self-help books for 16 months. Help Me! is self-deprecating and relatable, with some sweary Irish swagger thrown in. I can recommend it to self-help junkies and skeptics alike.

Help Me!: One Woman’s Quest to Find Out if Self-Help Really Can Change Her Life by Marianne Power: I have a particular weakness for year-challenge books, and Power’s is written in an easy, chatty style, as if Bridget Jones had given over her diary to testing self-help books for 16 months. Help Me! is self-deprecating and relatable, with some sweary Irish swagger thrown in. I can recommend it to self-help junkies and skeptics alike. Mrs Gaskell & Me: Two Women, Two Love Stories, Two Centuries Apart by Nell Stevens: Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive.

Mrs Gaskell & Me: Two Women, Two Love Stories, Two Centuries Apart by Nell Stevens: Stevens has a light touch, and flits between Gaskell’s story and her own in alternating chapters. This is a whimsical, sentimental, wry book that will ring true for anyone who’s ever been fixated on an idea or put too much stock in a relationship that failed to thrive. The Language of Kindness: A Nurse’s Story by Christie Watson: Watson presents her book as a roughly chronological tour through the stages of nursing – from pediatrics through to elderly care and the tending to dead bodies – but also through her own career. With its message of empathy for suffering and vulnerable humanity, it’s a book that anyone and everyone should read.

The Language of Kindness: A Nurse’s Story by Christie Watson: Watson presents her book as a roughly chronological tour through the stages of nursing – from pediatrics through to elderly care and the tending to dead bodies – but also through her own career. With its message of empathy for suffering and vulnerable humanity, it’s a book that anyone and everyone should read.

Two characters are reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (in Lily Brooks-Dalton’s Good Morning, Midnight and Julie Buntin’s Marlena) … I’ve since tried again with Le Guin’s book myself, but it’s so dry I can only bear to skim it.

Two characters are reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (in Lily Brooks-Dalton’s Good Morning, Midnight and Julie Buntin’s Marlena) … I’ve since tried again with Le Guin’s book myself, but it’s so dry I can only bear to skim it.

I’m reading Beryl Markham’s West with the Night … and then Glynnis MacNicol picks that very book up to read on a plane in No One Tells You This

I’m reading Beryl Markham’s West with the Night … and then Glynnis MacNicol picks that very book up to read on a plane in No One Tells You This

Two books set in Dunedin, New Zealand, one right after the other – I planned it that way, BUT both have a character called Myrtle (To the Is-Land by Janet Frame and Dunedin by Shena Mackay). Then I encountered Harold Gillies, the father of plastic surgery, in Jim McCaul’s Face to Face, and guess what? He was from Dunedin!

Two books set in Dunedin, New Zealand, one right after the other – I planned it that way, BUT both have a character called Myrtle (To the Is-Land by Janet Frame and Dunedin by Shena Mackay). Then I encountered Harold Gillies, the father of plastic surgery, in Jim McCaul’s Face to Face, and guess what? He was from Dunedin!

“Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” is mentioned in Little by Edward Carey and Marilla of Green Gables by Sarah McCoy

“Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” is mentioned in Little by Edward Carey and Marilla of Green Gables by Sarah McCoy

It’s not a place for the squeamish as there are mummified skeletons, details about Burke and Hare’s grave-robbing, surgical tools, and tumors and other anatomical deformities in jars everywhere. I found it all fascinating and spent a good two hours poking around. My favorite bits were the case full of foreign bodies removed from noses, stomachs and intestines and the temporary exhibition, “A Quest for Healing” by Zhang Yanzi, who had a residency at the museums in the summer of 2017. Her pieces included a 2D mountain made of pill packets, a cotton and gauze sculpture bristling with acupuncture needles, a matching hanging sculpture of capillaries, two surgical beds, and various silk screen panels.

It’s not a place for the squeamish as there are mummified skeletons, details about Burke and Hare’s grave-robbing, surgical tools, and tumors and other anatomical deformities in jars everywhere. I found it all fascinating and spent a good two hours poking around. My favorite bits were the case full of foreign bodies removed from noses, stomachs and intestines and the temporary exhibition, “A Quest for Healing” by Zhang Yanzi, who had a residency at the museums in the summer of 2017. Her pieces included a 2D mountain made of pill packets, a cotton and gauze sculpture bristling with acupuncture needles, a matching hanging sculpture of capillaries, two surgical beds, and various silk screen panels.

A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne is a delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view – first Erich Ackerman, whose Nazi-era history provides the basis for Maurice’s first novel; then Gore Vidal, to whose Italian home Maurice pays a visit with his new mentor; and finally Maurice’s wife Edith, a celebrated author in her own right – before getting Maurice’s own perspective. By this point we know enough about him to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is. My one criticism is that I would have binned the whole subplot about Edith’s sister and brother-in-law. (A nice touch: at one point Maurice buys a reprint copy of Maude Avery’s Like to the Lark, which should ring a bell from

A Ladder to the Sky by John Boyne is a delicious piece of literary suspense with a Tom Ripley-like hero you’ll love to hate: Maurice Swift, who wants nothing more than to be a writer but doesn’t have any ideas of his own, so steals them from other people. I loved how we see this character from several outside points of view – first Erich Ackerman, whose Nazi-era history provides the basis for Maurice’s first novel; then Gore Vidal, to whose Italian home Maurice pays a visit with his new mentor; and finally Maurice’s wife Edith, a celebrated author in her own right – before getting Maurice’s own perspective. By this point we know enough about him to understand just how unreliable a narrator he is. My one criticism is that I would have binned the whole subplot about Edith’s sister and brother-in-law. (A nice touch: at one point Maurice buys a reprint copy of Maude Avery’s Like to the Lark, which should ring a bell from  I also read over half of Jenny Diski’s Stranger on a Train, a memoir about two long train journeys she took across America in the late 1990s that also incorporates memories from a troubled adolescence – she started smoking at 14 and was in and out of mental hospitals at 15 – in which she loved nothing more than to read while riding the Circle line all day long. I’m a quarter of the way through both Nancy Horan’s Under the Wide and Starry Sky, about Stevenson and his wife, and Peter Hill’s Stargazing, a memoir about dropping out of art school to become a Scottish lighthouse keeper in 1973; he started on Pladda, a tiny island off of Arran. And on my Nook I read a good bit of All You Can Ever Know, Nicole Chung’s forthcoming memoir about being raised by adoptive white parents in Oregon and meeting members of her Korean family in her mid-twenties, just as she became a mother herself.

I also read over half of Jenny Diski’s Stranger on a Train, a memoir about two long train journeys she took across America in the late 1990s that also incorporates memories from a troubled adolescence – she started smoking at 14 and was in and out of mental hospitals at 15 – in which she loved nothing more than to read while riding the Circle line all day long. I’m a quarter of the way through both Nancy Horan’s Under the Wide and Starry Sky, about Stevenson and his wife, and Peter Hill’s Stargazing, a memoir about dropping out of art school to become a Scottish lighthouse keeper in 1973; he started on Pladda, a tiny island off of Arran. And on my Nook I read a good bit of All You Can Ever Know, Nicole Chung’s forthcoming memoir about being raised by adoptive white parents in Oregon and meeting members of her Korean family in her mid-twenties, just as she became a mother herself.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This atmospheric novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch is no happy family story; it’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate, yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right. I recently caught up on Fuller’s acclaimed 2015 debut, Our Endless Numbered Days, and collectively I’m so impressed with her work, specifically the elegant way she alternates between time periods to gradually reveal the extent of family secrets and the faultiness of memory.

Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller: This atmospheric novel reminiscent of Iris Murdoch is no happy family story; it’s full of betrayals and sadness, of failures to connect and communicate, yet it’s beautifully written, with all its scenes and dialogue just right. I recently caught up on Fuller’s acclaimed 2015 debut, Our Endless Numbered Days, and collectively I’m so impressed with her work, specifically the elegant way she alternates between time periods to gradually reveal the extent of family secrets and the faultiness of memory.

All the Spectral Fractures: New and Selected Poems, Mary A. Hood: There is so much substance and variety to this poetry collection spanning the whole of Hood’s career. A professor emerita of microbiology at the University of West Florida and a former poet laureate of Pensacola, Florida, she takes inspiration from the ordinary folk of the state, the world of academic scientists, flora and fauna, and the minutiae of everyday life.

All the Spectral Fractures: New and Selected Poems, Mary A. Hood: There is so much substance and variety to this poetry collection spanning the whole of Hood’s career. A professor emerita of microbiology at the University of West Florida and a former poet laureate of Pensacola, Florida, she takes inspiration from the ordinary folk of the state, the world of academic scientists, flora and fauna, and the minutiae of everyday life.

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis: Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!).

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis: Time travel would normally be a turnoff for me, but Willis manages it perfectly in this uproarious blend of science fiction and pitch-perfect Victorian pastiche (boating, séances and sentimentality, oh my!). Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi: Brings together so many facets of the African and African-American experience; full of clear-eyed observations about the ongoing role race plays in American life.

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi: Brings together so many facets of the African and African-American experience; full of clear-eyed observations about the ongoing role race plays in American life.

Signs for Lost Children by Sarah Moss: Simply superb in the way it juxtaposes England and Japan in the 1880s and comments on mental illness, the place of women, and the difficulty of navigating a marriage whether the partners are thousands of miles apart or in the same room.

Signs for Lost Children by Sarah Moss: Simply superb in the way it juxtaposes England and Japan in the 1880s and comments on mental illness, the place of women, and the difficulty of navigating a marriage whether the partners are thousands of miles apart or in the same room. Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler: I’ve been lukewarm on Anne Tyler’s novels before – this is my sixth from her – but this instantly leapt onto my list of absolute favorite books. Its chapters are like perfectly crafted short stories focusing on different members of the Tull family. These vignettes masterfully convey the common joys and tragedies of a fractured family’s life. After Beck Tull leaves with little warning, Pearl must raise Cody, Ezra and Jenny on her own and struggle to keep her anger in check. Cody is a vicious prankster who always has to get the better of good-natured Ezra; Jenny longs for love but keeps making bad choices. Despite their flaws, I adored these characters and yearned for them to sit down, even just the once, to an uninterrupted family dinner of comfort food.

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler: I’ve been lukewarm on Anne Tyler’s novels before – this is my sixth from her – but this instantly leapt onto my list of absolute favorite books. Its chapters are like perfectly crafted short stories focusing on different members of the Tull family. These vignettes masterfully convey the common joys and tragedies of a fractured family’s life. After Beck Tull leaves with little warning, Pearl must raise Cody, Ezra and Jenny on her own and struggle to keep her anger in check. Cody is a vicious prankster who always has to get the better of good-natured Ezra; Jenny longs for love but keeps making bad choices. Despite their flaws, I adored these characters and yearned for them to sit down, even just the once, to an uninterrupted family dinner of comfort food.