Reviewing Two Books by Cancelled Authors

I don’t have anything especially insightful to say about these authors’ reasons for being cancelled, although in my review of the Clanchy I’ve noted the textual examples that have been cited as problematic. Alexie is among the legion of male public figures to have been accused of sexual misconduct in recent years. I’m not saying those aren’t serious allegations, but as Claire Dederer wrestled with in Monsters, our judgement of a person can be separate from our response to their work. So that’s the good news: I thought these were both fantastic books. They share a theme of education.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (illus. Ellen Forney) (2007)

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

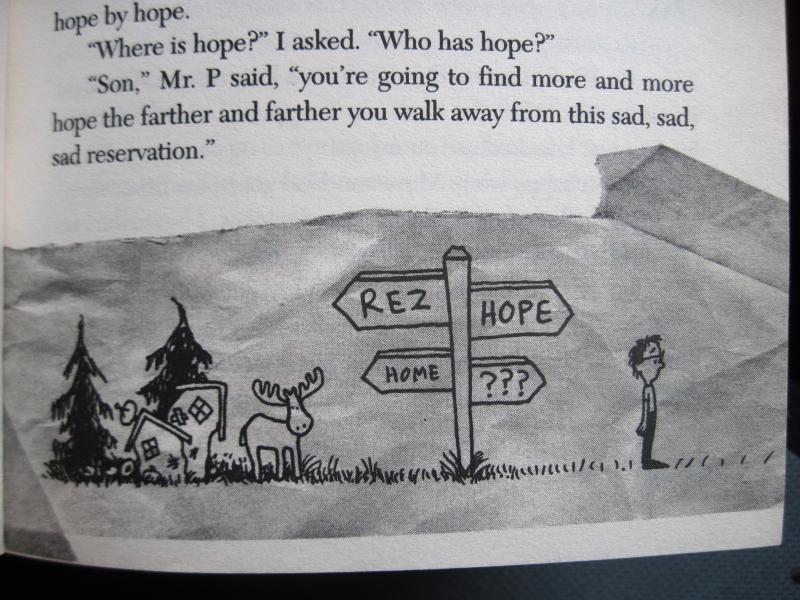

It reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable; Alexie’s tone is spot on. Junior has had a tough life on a Spokane reservation in Washington, being bullied for his poor eyesight and speech impediments that resulted from brain damage at birth and ongoing seizures. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations here because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior’s parents never got to pursue their dreams and his sister has run away to Montana, but he has a chance to change the trajectory. A rez teacher says his only hope for a bright future is to transfer to the elite high school in Reardan. So he does, even though it often requires hitch-hiking or walking miles.

Junior soon becomes adept at code-switching: “Traveling between Reardan and Wellpinit, between the little white town and the reservation, I always felt like a stranger. I was half Indian in one place and half white in the other.” He gets a white girlfriend, Penelope, but has to work hard to conceal how impoverished he is. His best friend, Rowdy, is furious with him for abandoning his people. That resentment builds all the way to a climactic basketball match between Reardan and Wellpinit that also functions as a symbolic battle between the parts of Junior’s identity. Along the way, there are multiple tragic deaths in which alcohol, inevitably, plays a role. “I’m fourteen years old and I’ve been to forty-two funerals,” he confides. “Jeez, what a sucky life. … I kept trying to find the little pieces of joy in my life. That’s the only way I managed to make it through all of that death and change.”

One of those joys, for him, is cartooning. Describing his cartoons to his new white friend, Gordy, he says, “I use them to understand the world.”

Forney’s black-and-white illustrations make the cartoons look like found objects – creased scraps of notebook paper sellotaped into a diary. This isn’t a graphic novel, but most of the short chapters include several illustrations. There’s a casual intimacy to the whole book that feels absolutely authentic. Bridging the particular and universal, it’s a heartfelt gem, and not just for teens. (University library) ![]()

Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy (2019)

If your Twitter sphere and mine overlap, you may remember the controversy over the racialized descriptions in this Orwell Prize-winning memoir of 30 years of teaching – and the fact that, rather than issuing a humbled apology, Clanchy, at least initially, doubled down and refuted all objections, even when they came from BIPOC. It wasn’t a good look. Nor was it the first time I’ve found Clanchy to be prickly. (She is what, in another time, might have been called a formidable woman.) Anyway, I waited a few years for the furore to die down before trying this for myself.

I know vanishingly little about the British education system because I don’t have children and only experienced uni here at a distance, through my junior year abroad. So there may be class-based nuances I missed – for instance, in the chapter about selecting a school for her oldest son and comparing it with the underprivileged Essex school where she taught. But it’s clear that a lot of her students posed serious challenges. Many were refugees or immigrants, and she worked for a time on an “Inclusion Unit,” which seems to be more in the business of exclusion in that it’s for students who have been removed from regular classrooms. They came from bad family situations and were more likely to end up in prison or pregnant. To get any of them to connect with Shakespeare, or write their own poetry, was a minor miracle.

Clanchy is also a poet and novelist – I’ve read one of her novels, and her Selected Poems – and did much to encourage her students to develop a voice and the confidence to have their work published (she’s produced anthologies of student work). In many cases, she gave them strategies for giving literary shape to traumatic memories. The book’s engaging vignettes have all had the identifying details removed, and are collected under thematic headings that address the second part of the title: “About Love, Sex, and the Limits of Embarrassment” and “About Nations, Papers, and Where We Belong” are two example chapters. She doesn’t avoid contentious topics, either: the hijab, religion, mental illness and so on.

You get the feeling that she was a friend and mentor to her students, not just their teacher, and that they could talk to her about anything and rely on her support. Watching them grow in self-expression is heart-warming; we come to care for these young people, too, because of how sincerely they have been created from amalgams. Indeed, Clanchy writes in the introduction that “I have included nobody, teacher or pupil, about whom I could not write with love.”

And that is, I think, why she was so hurt and disbelieving when people pointed out racism in her characterization:

I was baffled when a boy with jet-black hair and eyes and a fine Ashkenazi nose named David Marks refused any Jewish heritage

her furry eyebrows, her slanting, sparking black eyes, her general, Mongolian ferocity. [but she’s Afghan??]

(of girls in hijabs) I never saw their (Asian/silky/curly?) hair in eight years.

They’re a funny pair: Izzat so small and square and Afghan with his big nose and premature moustache; Mo so rounded and mellow and Pakistani with his long-lashed eyes and soft glossy hair.

There are a few other ill-advised passages. She admits she can’t tell the difference between Kenyan and Somali faces; she ponders whether being a Scot in England gave her some taste of the prejudice refugees experience. And there’s this passage about sexuality:

Are we all ‘fluid’ now? Perhaps. It is commonplace to proclaim oneself transsexual. And to actually be gay, especially if you are as pretty as Kristen Stewart, is positively fashionable. A couple of kids have even changed gender, a decision … deliciously of the moment

My take: Clanchy wanted to craft affectionate pen portraits that celebrated children’s uniqueness, but had to make them anonymous, so resorted to generalizations. Doing this on a country or ethnicity basis was the mistake. Journalistic realism doesn’t require a focus on appearances (I would hope that, if I were ever profiled, someone could find more interesting things to say about me than that I am short and have a large nose). She could have just introduced the students with ‘facts,’ e.g., “Shakila, from Afghanistan, wore a hijab and was feisty and outspoken.” Note to self: white people can be clueless, and we need to listen and learn. The book was reissued in 2022 by independent publisher Swift Press, with offending passages removed (see here for more info). I’d be keen to see the result and hope that the book will find more readers because, truly, it is lovely. (Little Free Library) ![]()

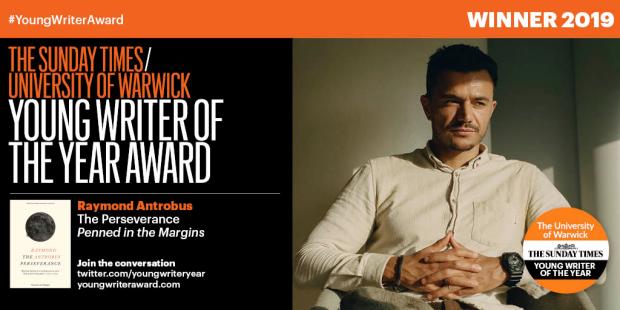

Young Writer of the Year Award Ceremony

It was great to be back at the London Library for last night’s Young Writer of the Year Award prize-giving ceremony. I got to meet Anne Cater (Random Things through my Letterbox) from the shadow panel, who’s coordinated a few blog tours I’ve participated in, as well as Ova Ceren (Excuse My Reading). It was also good to see shadow panelist Linda (Linda’s Book Bag) again and hang out with Clare (A Little Blog of Books), also on the shadow panel in my year, and Eric (Lonesome Reader), who seems to get around to every London literary event.

In case you haven’t heard, the shadow panel chose Salt Slow by Julia Armfield as their very deserving winner, but the official winner was Raymond Antrobus for his poetry collection The Perseverance. In all honesty, I’d given no thought to the possibility of it winning, mostly because Antrobus has already won several major prizes for the book, including this year’s £30,000 Rathbones Folio Prize (I reviewed it for the Prize’s blog tour). Now, there’s no rule saying you can’t win multiple prizes for the same book, but what struck me strangely about this case is that Kate Clanchy was a judge for both the Folio Prize and the Young Writer Award.

In case you haven’t heard, the shadow panel chose Salt Slow by Julia Armfield as their very deserving winner, but the official winner was Raymond Antrobus for his poetry collection The Perseverance. In all honesty, I’d given no thought to the possibility of it winning, mostly because Antrobus has already won several major prizes for the book, including this year’s £30,000 Rathbones Folio Prize (I reviewed it for the Prize’s blog tour). Now, there’s no rule saying you can’t win multiple prizes for the same book, but what struck me strangely about this case is that Kate Clanchy was a judge for both the Folio Prize and the Young Writer Award.

Antrobus seemed genuinely taken aback by his win and gave a very gracious speech in which he said that he looked forward to all the shortlistees contributing to the canon of English literature. He was quickly whisked away for a photo shoot, so I didn’t get a chance to congratulate him or have my book signed, but I did get to meet Julia Armfield and Yara Rodrigues Fowler and get their autographs.

Some interesting statistics for you: in three of the past four years the shadow panel has chosen a short story collection as its winner (and they say no one likes short stories these days!). In none of those four years did the shadow panel correctly predict the official winner – so, gosh, is it the kiss of death to be the shadow panel winner?!

In the official press release, chair of judges and Sunday Times literary editor Andrew Holgate writes that The Perseverance is “both very personal and immensely resonant. The result is a memoir in verse very, very affecting and fresh.” Poet Kate Clanchy adds, “we wanted to find a writer who both speaks for now and who we were confident would continue to produce valuable, central work. … it was the humanity of the book, its tempered kindness, and the commitment not just to recognising difference but to the difficult act of forgiveness that made us confident we had found a winner for this extraordinary year.”

In the official press release, chair of judges and Sunday Times literary editor Andrew Holgate writes that The Perseverance is “both very personal and immensely resonant. The result is a memoir in verse very, very affecting and fresh.” Poet Kate Clanchy adds, “we wanted to find a writer who both speaks for now and who we were confident would continue to produce valuable, central work. … it was the humanity of the book, its tempered kindness, and the commitment not just to recognising difference but to the difficult act of forgiveness that made us confident we had found a winner for this extraordinary year.”

Also present at the ceremony were Sarah Moss (who teaches at the University of Warwick, the Award’s new co-sponsor) and Katya Taylor. I could have sworn I spotted Deborah Levy, too, but after conferring with other book bloggers we decided it was just someone who looked a lot like her.

In any event, it was lovely to see London all lit up with Christmas lights and to spend a couple of hours celebrating up-and-coming writing talent. (And I just managed to catch the last train home and avoid a rail replacement bus nightmare.)

Looking forward to next year already!

My Life in Book Quotes

I keep an ongoing Word file with details on my year’s reading: books finished with the date, number of pages, and source – similar information to what’s recorded on Goodreads – plus any quotations that particularly stood out to me. It occurred to me that by looking back through these annual book lists for the quotes that meant the most to me I could probably narrate my recent years. So here are the 2015–2016 quotes that tell my story.

Career

“I’m learning that what’s important is not so much what I do to make a living as who I become in the process. … the heroine, when at a juncture, makes her own choice—the nonheroine lets others make it for her.”

(A Year by the Sea: Thoughts of an Unfinished Woman, Joan Anderson)

“The dishes. The dishes! The goddamn dishes! No wonder women don’t succeed.”

(The author’s mother’s explosion in The Year My Mother Came Back, Alice Eve Cohen)

“Success says, What more can I get?

Craft says, Can you believe I get to do this?”

(How to Be Here: A Guide to Creating a Life Worth Living, Rob Bell)

“Amateurs look for inspiration; the rest of us just get up and go to work.”

(Everyman, Philip Roth)

Finding a Home

“In Orcadian, ‘flitting’ means ‘moving house’. I can hear it spoken with a tinge of disapproval or pity: the air-headed English couple who couldn’t settle.”

(The Outrun, Amy Liptrot)

“Where, after we have made the great decision to leave the security of childhood and move on into the vastness of maturity, does anybody ever feel completely at home?”

(A Circle of Quiet, Madeleine L’Engle)

“there is no such thing / as the right route or a clear passage / no matter where you start, / or how you plan it.”

(from “Aneurysm,” Selected Poems, Kate Clanchy)

Life vs. Books

“He had accepted that if you were a bookish person the events in your life took place in your head.”

(Golden Age, Jane Smiley)

“my way of seeing has always been different, shyer. To see the world I’ve always opened a book.”

(The Violet Hour: Great Writers at the End, Katie Roiphe)

“Other people’s lives, and the lives I read about in books, seem richer, mine seems so threadbare.”

(The Past, Tessa Hadley)

Overthinking

“She remembered finding her first white hair somewhere near her thirtieth birthday and it had sent her on a tailspin for half a day. It’s starting, she’d thought then. The follicle that produced that hair is dying. I’ve reached the tipping point and from now on it’s nothing but slow decline.”

(Dog Run Moon: Stories, Callan Wink)

“All the most terrifying Ifs involve people. All the good ones do as well.”

(A Little Life, Hanya Yanagihara)

“I wished then, and still do, that there was something in me also that would march steadily in one road, instead of down here or there or somewhere else, the mind running a net of rabbit-paths that twisted and turned and doubled on themselves, pursued always by the hawk-shadow of doubt.”

(Now in November, Josephine Johnson – to be reviewed here within next couple weeks)

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.