Reading about Mothers and Motherhood: Cosslett, Cusk, Emma Press Poetry, Heti, and Pachico

It was (North American) Mother’s Day at the weekend, an occasion I have complicated feelings about now that my mother is gone. But I don’t think I’ll ever stop reading and writing about mothering. At first I planned to divide my recent topical reads (one a reread) into two sets, one for ambivalence about becoming a mother and the other for mixed feelings about one’s mother. But the two are intertwined – especially in the poetry anthology I consider below – such that they feel more like facets of the same experience. I also review two memoirs (one classic; one not so much) and two novels (autofiction vs. science fiction).

The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett (2023)

This was on my Most Anticipated list last year. A Covid memoir that features adopting a cat and agonizing over the question of whether to have a baby sounded right up my street. And in the earlier pages, in which Cosslett brings Mackerel the kitten home during the first lockdown and interrogates the stereotype of the crazy cat lady from the days of witches’ familiars onwards, it indeed seemed to be so. But the further I got, the more my pace through the book slowed to a limp; it took me 10 months to read, in fits and starts.

I’ve struggled to pinpoint what I found so off-putting, but I have a few hypotheses: 1) By the time I got hold of this, I’d tired of Covid narratives. 2) Fragmentary narratives can seem like profound reflections on subjectivity and silences. But Cosslett’s strategy of bouncing between different topics – worry over her developmentally disabled brother, time working as an au pair in France, PTSD from an attempted strangling by a stranger in London and being in Paris on the day of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack – with every page or even every paragraph, feels more like laziness or arrogance. Of course the links are there; can’t you see them?

I’ve struggled to pinpoint what I found so off-putting, but I have a few hypotheses: 1) By the time I got hold of this, I’d tired of Covid narratives. 2) Fragmentary narratives can seem like profound reflections on subjectivity and silences. But Cosslett’s strategy of bouncing between different topics – worry over her developmentally disabled brother, time working as an au pair in France, PTSD from an attempted strangling by a stranger in London and being in Paris on the day of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack – with every page or even every paragraph, feels more like laziness or arrogance. Of course the links are there; can’t you see them?

3) Cosslett claims to reject clichéd notions about pets being substitutes for children, then goes right along with them by presenting Mackerel as an object of mothering (“there is something about looking after her that has prodded the carer in me awake”) and setting up a parallel between her decision to adopt the kitten and her decision to have a child. “Though I had all these very valid reasons not to get a cat, I still wanted one,” she writes early on. And towards the end, even after she’s considered all the ‘very valid reasons’ not to have a baby, she does anyway. “I need to find another way of framing it, if I am to do it,” she says. So she decides that it’s an expression of bravery, proof of overcoming trauma. I was unconvinced. When people accuse memoirists of being navel-gazing, this is just the sort of book they have in mind. I wonder if those familiar with her Guardian journalism would agree. (Public library)

A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother by Rachel Cusk (2001)

When this was first published, Cusk was vilified for “hating” her child – that is, for writing honestly about the bewilderment and misery of early motherhood. We’ve moved on since then. Now women are allowed to admit that it’s not all cherubs and lullabies. I suspect what people objected to was the unemotional tone: Cusk writes like an anthropologist arriving in a new land. The style is similar to her novels’ in that she can seem detached because of her dry wit, elevated diction and frequent literary allusions.

When this was first published, Cusk was vilified for “hating” her child – that is, for writing honestly about the bewilderment and misery of early motherhood. We’ve moved on since then. Now women are allowed to admit that it’s not all cherubs and lullabies. I suspect what people objected to was the unemotional tone: Cusk writes like an anthropologist arriving in a new land. The style is similar to her novels’ in that she can seem detached because of her dry wit, elevated diction and frequent literary allusions.

I understand that crying, being the baby’s only means of communication, has any number of causes, which it falls to me, as her chief companion and link to the world, to interpret.

Have you taken her to toddler group, the health visitor enquired. I had not. Like vaccinations and mother and baby clinics, the notion instilled in me a deep administrative terror.

We [new parents] are heroic and cruel, authoritative and then servile, cleaving to our guesses and inspirations and bizarre rituals in the absence of any real understanding of what we are doing or how it should properly be done.

She approaches mumsy things as an outsider, clinging to intellectualism even though it doesn’t seem to apply to this new world of bodily obligation, “the rambling dream of feeding and crying that my life has become.” By the end of the book, she does express love for and attachment to her daughter, built up over time and through constant presence. But she doesn’t downplay how difficult it was. “For the first year of her life work and love were bound together, fiercely, painfully.” This is a classic of motherhood literature, and more engaging than anything else I’ve read by Cusk. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)

The Emma Press Anthology of Motherhood, ed. by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright (2014)

There’s a great variety of subject matter and tone here, despite the apparently narrow theme. There are poems about pregnancy (“I have a comfort house inside my body” by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi), childbirth (“The Tempest” by Melinda Kallismae) and new motherhood, but also pieces imagining the babies that never were (“Daughters” by Catherine Smith) or revealing the complicated feelings adults have towards their mothers.

“All My Mad Mothers” by Jacqueline Saphra depicts a difficult bond through absurdist metaphors: “My mother was so hard to grasp: once we found her in a bath / of olive oil, or was it sesame, her skin well-slicked / … / to ease her way into this world. Or out of it.” I also loved her evocation of a mother–daughter relationship through a rundown of a cabinet’s contents in “My Mother’s Bathroom Armoury.”

In “My Mother Moves into Adolescence,” Deborah Alma expresses exasperation at the constant queries and calls for help from someone unconfident in English. “This, then, is how you should pray” by Flora de Falbe cleverly reuses the structure of the Lord’s Prayer as she sees her mother returning to independent life and a career as her daughter prepares to leave home. “I will hold you / as you held me / my mother – / yours are the bathroom catalogues / and the whole of a glorious future.”

In “My Mother Moves into Adolescence,” Deborah Alma expresses exasperation at the constant queries and calls for help from someone unconfident in English. “This, then, is how you should pray” by Flora de Falbe cleverly reuses the structure of the Lord’s Prayer as she sees her mother returning to independent life and a career as her daughter prepares to leave home. “I will hold you / as you held me / my mother – / yours are the bathroom catalogues / and the whole of a glorious future.”

I connected with these perhaps more so than the poems about becoming a mother, but there are lots of strong entries and very few unmemorable ones. Even within the mothers’ testimonials, there is ambivalence: the visceral vocabulary in “Collage” by Anna Kisby is rather morbid, partway to gruesome: “You look at me // like liver looks at me, like heart. You are familiar as innards. / In strip-light I clean your first shit. I’m not sure I do it right. / It sticks to me like funeral silk. … There is a window // guillotined into the wall. I scoop you up like a clod.”

A favourite pair: “Talisman” by Anna Kirk and “Grasshopper Warbler” by Liz Berry, on facing pages, for their nature imagery. “Child, you are grape / skins stretched over fishbones. … You are crab claws unfurling into cabbage leaves,” Kirk writes. Berry likens pregnancy to patient waiting for an elusive bird by a reedbed. (Free copy – newsletter giveaway)

Motherhood by Sheila Heti (2018)

I first read this nearly six years ago (see my original review), when I was 34; I’m now 40 and pretty much decided against having children, but FOMO is a lingering niggle. Even though I already owned it in hardback, I couldn’t resist picking up a nearly new paperback I saw going for 50 pence in a charity shop, if only for the Leanne Shapton cover – her simple, elegant watercolour style is instantly recognizable. Having a different copy also provided some novelty for my reread, which is ongoing; I’m about 80 pages from the end.

I’m not finding Heti’s autofiction musings quite as profound this time around, and I can’t deny that the book is starting to feel repetitive, but I’ve still marked more than a dozen passages. Pondering whether to have children is only part of the enquiry into what a woman artist’s life should be. The intergenerational setup stands out to me again as Heti compares her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s short life with her mother’s practical career and her own creative one.

I’m not finding Heti’s autofiction musings quite as profound this time around, and I can’t deny that the book is starting to feel repetitive, but I’ve still marked more than a dozen passages. Pondering whether to have children is only part of the enquiry into what a woman artist’s life should be. The intergenerational setup stands out to me again as Heti compares her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s short life with her mother’s practical career and her own creative one.

For the past month or so, I’ve also been reading Alphabetical Diaries, so you could say that I’m pretty Heti-ed out right now, but I do so admire her for writing exactly what she wants to and sticking to no one else’s template. People probably react against Heti’s work as self-indulgent in the same way I did with Cosslett’s, but the former’s shtick works for me. (Secondhand purchase – Bas Books & Home, Newbury)

A few of the passages that have most struck me on this second reading:

I think that is how childbearing feels to me: a once-necessary, now sentimental gesture.

I don’t want ‘not a mother’ to be part of who I am—for my identity to be the negative of someone else’s positive identity.

The whole world needs to be mothered. I don’t need to invent a brand new life to give the warming effect to my life I imagine mothering will bring.

I have to think, If I wanted a kid, I already would have had one by now—or at least I would have tried.

Jungle House by Julianne Pachico (2023)

{BEWARE SPOILERS}

Pachico’s third novel is closer to sci-fi than I might have expected. Apart from Lena, the protagonist, all the major characters are machines or digital recreations: AI, droids, a drone, or a holograph of the consciousness of a dead girl. “Mother” is the AI security system that controls Jungle House, the Morel family’s vacation home in a country that resembles Colombia, where Pachico grew up and set her first two books. Lena, as the human caretaker, is forever grateful to Mother for rescuing her as a baby after the violent death of her parents, who were presumed rebels.

Pachico’s third novel is closer to sci-fi than I might have expected. Apart from Lena, the protagonist, all the major characters are machines or digital recreations: AI, droids, a drone, or a holograph of the consciousness of a dead girl. “Mother” is the AI security system that controls Jungle House, the Morel family’s vacation home in a country that resembles Colombia, where Pachico grew up and set her first two books. Lena, as the human caretaker, is forever grateful to Mother for rescuing her as a baby after the violent death of her parents, who were presumed rebels.

Mother is exacting but mercurial, strict about cleanliness yet apt to forget or overlook things during one of her “spells.” Lena pushes the boundaries of her independence, believing that Mother only wants to protect her but still longing to explore the degraded wilderness beyond the compound.

Mother was right, because Mother was always right about these kinds of things. The world was a complicated place, and Mother understood it much better than she did.

In the house, there was no privacy. In the house, Mother saw all.

Mother was Lena’s world. And Lena, in turn, was hers. No matter how angry they got at each other, no matter how much they fought, no matter the things that Mother did or didn’t do … they had each other.

It takes a while to work out just how tech-reliant this scenario is, what the repeated references to “the pit bull” are about, and how Lena emulated and resented Isabella, the Morel daughter, in equal measure. Even creepier than the satellites’ plan to digitize humans is the fact that Isabella’s security drone, Anton, can fabricate recorded memories. This reminded me a lot of Klara and the Sun. Tech themes aren’t my favourite, but I ultimately thought of this as an allegory of life with a narcissistic mother and the child’s essential task of breaking free. It’s not clinical and contrived, though; it’s a taut, subtle thriller with an evocative setting. (Public library)

See also: “Three on a Theme: Matrescence Memoirs”

Does one or more of these books take your fancy?

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

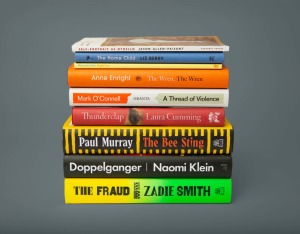

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?”

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?” Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension:

Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension: Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

So I’m ambivalent about winter, and was interested to see how the authors collected in Melissa Harrison’s final seasonal anthology would explore its inherent contradictions. I especially appreciated the views of outsiders. Jini Reddy, a Quebec native, calls British winters “a long, grey sigh or a drawn-out ache.” In two of my favorite pieces, Christina McLeish and Nakul Krishna – from Australia and India, respectively – compare the warm, sunny winters they experienced in their homelands with their early experiences in Britain. McLeish remembers finding a disembodied badger paw on a frosty day during one of her first winters in England, while Krishna tells of a time he spent dogsitting in Oxford when all the students were on break. His decorous, timeless prose reminded me of J.R. Ackerley’s.

So I’m ambivalent about winter, and was interested to see how the authors collected in Melissa Harrison’s final seasonal anthology would explore its inherent contradictions. I especially appreciated the views of outsiders. Jini Reddy, a Quebec native, calls British winters “a long, grey sigh or a drawn-out ache.” In two of my favorite pieces, Christina McLeish and Nakul Krishna – from Australia and India, respectively – compare the warm, sunny winters they experienced in their homelands with their early experiences in Britain. McLeish remembers finding a disembodied badger paw on a frosty day during one of her first winters in England, while Krishna tells of a time he spent dogsitting in Oxford when all the students were on break. His decorous, timeless prose reminded me of J.R. Ackerley’s.